HSCA Volume VI: IV. Conspiracy Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ex-Spy Says She Drove to Dallas with Oswald & Kennedy 'Assassin

Ex-Spy Says She Drove To Dallas With Oswald & Kennedy 'Assassin Squad' By PAUL MESKIL A former spy says that she accompanied Lee Harvey Oswald and an "assassin squad" to Dallas a few days before President Kennedy was murdered there Nov. 22, 1963. The House Assassinations Committee is investigating her story. Marita Lorenz, former undercov- er operative for the CIA and FBI, told The News that her companions on the car trip from Miami to Dallas were Os. wald, CIA contract agent Frank Sturgis, Cuban exile leaders Orlando Bosch and Pedro Diaz Lanz, and two Cuban broth- ers whose names she does not know. She said they were all members of Operation 40, a secret guerrilla group originally formed by the CIA in 1960 in preparation for the Bay of Pigs inva- sion. Statements she made to The News and to a federal agent were reported to Robert Blakey, chief counsel of the Assassinations Committee. He has as- signed one of his top investigators to interview her. Ms. Lorenz described Operation 40 as an ''assassination squad" consisting of about 30 anti-Castro Cubans and their American advisers. She claimed the group conspired to kill Cuban Premier Fidel Castro and President Kennedy, whom it blamed for the Bay of Pigs fiasco. Admitted Taking Part Sturgis admitted in an interview two years ago that he took part in Opera- Maritza Lorenz tion 40. "There are reports that Opera- Farmer CIA agent tion 40 had an assassination squad." he said. "I'm not saying that personally ... In the summer or early fall of 1963. -

John Greenewald, Jr., Creator Of: the Black Vault

This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION FOI/PA DELETED PAGE INFORMATION SHEET FOI/PA# 1212526-0 Total Deleted Page(s) = 12 Page 30 - Referral/Consult; Page 31 - Referral/Consult; Page 50 - Referral/Direct; Page 51 - Referral/Direct; Page 52 - Referral/Direct; Page 53 - Referral/Direct; Page 54 - Referral/Direct; Page 55 - Referral/Direct; Page 56 - Referral/Direct; Page 57 - Referral/Direct; Page 58 - Referral/Direct; Page 59 - Referral/Direct; xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx X Deleted Page(s) X X No Duplication Fee X X For this Page X xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx P'7,,____y =___ E!:)-36 (Rev. 11-17-88) ~- FBI TRANSMIT VIA: PRECEDENCE: CLASSIFICATION:• 0 Teletype 0 Immediate 0 TOP SECRET 0 Facsimile 0 Priority 0 SECRET !KJ AIRTEL 0 Routine 0 CONFIDENTIAL 0 UNCLAS E F T 0 0 UNCLAS Date 11/19/92 INVEST DIV, DOMESTIC TERRORISM UNIT b6 (2 MM-61560) (FCI-1) (P) b7C ,..;; b6 aka - I I b7C AL; OF 0 I ( Reference FBIHQ te1ca1l to Miami 11/17/92. Enclosed for FBIHQ are three copies of a sel~ explanatory LHM suitable for dissemination. Per referenced telcall advising of DOJ authority, Miami has initiated a Neutrality case on captioned matter. b6 ~~~~~~lis a well known anti-Castro activist in the Miami b7c ____The following is a descrigtion o~ NAME RACE b6 __{jJ__ SEX.* = DOB b7Cc=J ~ -~ SSAN All INFORMATION CONTAINED "i"LA DL HEREIN IS UNCLASSIFIED. -

`JFK' Premiere • JFK Slayers `Found' on Grassy Knoll

Pate l ci 6 Stone, guests JFK slayers make plans for `found' on `JFK' premiere • grassy knoll By Jane Sumner By Mark Potok (t-14-?1 sir Write of The Wks Morning Fews OF THE TIMES HERALD STAFF 1FR, the film that Variety calls "an You may too sure political conspiracy not be incendiary what Tom Wilson is showing thriller," premieres in Dallas at a ben- you when he starts his video, efit screening Dec. 19 at General but it's hard to ignore the re- Cinema's NorthPark 1 and 11 theatres- tired engineer's words. Oscar-winning di rector Oliver "You are looking right now Stone and guests will attend a recap. into the eye of the assassin of President Kennedy," he says FILM evenly as the tape rolls. tion at Newport's in The Brewery, 703 "You're looking at a mole on McKinney Ave.. after the 7 p.m. his cheek. screening. Gary Oldinan, who plays "1 can tell you right now, Lee Harvey Oswald in the three-hour his eyes are brown." film, has been mentioned as one of the Using sophisticated tech- stars who may accompany Mr. Stone. nologies known as "image JFK, which filmed in Dallas in processing" and "spectral April and May, stars Kevin Costner as analysis," Wilson, 59, has Jim Garrison, the New Orleans district spent three years examining attorney who prosecuted the only some of the most famous criminal case connected with the mur- photographs and films of the der. Others in the all-star cast include world's most famous assassi- Sissy Spacek, Tommy Lee Jones, Joe nation. -

Commission on CIA Activities Within the United States: Chapter 19

Chapter 19 Allegations Concerning the Assassination of President Kenned@ ,Illegations hare been made that the CIA participated in the assassination of President ,John F. Kennedy in Dallas, Texas. on h’ovember 22. 1963. Two different. theories have been advanced in support of those allegations. One theory is that E. Howard Hunt and Frank Sturgis, on behalf of the CIA, personally participated in the assassination. The other is that the CIA had connections with Lee Harvey Oswald or Jack Ruby. or both of them. and that those connections somehow led to t.he assassination. The Commission staff has investigated these allegations. Neither the staff nor the Commission undertook a full review of the Report of the Warren Commission. Such a task would have been outsicle the scope of the Executive Order establishing this Commis- sion, and would hare diverted the time of the Commission from its proper function. The investigation was limited to determining whether there was any credible evidence pointing to CIA involvement in the assassination of President Kennedy. A. The Theory That Hunt and Sturgis Participated in the Assassination The first of t.he theories involves charges that E. Howard Hunt and Frank Sturgis, both convicted of burglarizing the Democrst:ic Na- tional Committee headquarters at the Watergate in 1972, were CIA employees or agents at the time of the assassination of the President in 1963. It is further alleged that they were together in Dallas on the day of the assassination and that shortly after the assassination they were found in a railroad boxcar situated behind the “grassy knoll,” an area located to the right front of the Presidential car at the time of the assassination. -

CIA Agent Confesses Plotting

LA VERDAD NO SE PUEDE TAPIR CON TODA LA TIERRA 4/12/75 DEL MUNDO. knew to be connected with the CAA, he said. His own rule had been limited to Jack Anderson helping "set up" assassination attempts. He had never taken part in any actual murders, he swore. All the assassination plots, he explain- CIA agent ed, had been aimed against foreign lead- ers, none against American citizens. Most of the attempts had failed, he said, al- confesses though he was involved in the advanc4 work that led to the successful assassina- tion of Dictator Trujillo in the Dominican plotting Republic. Sturgis described Cuba as the "hub" of WASHINGTON — In secret testimony assassination schemes. He personally had- before the Rockefeller Commiision, participated in plots, he said, against.. Watergate burglar Frank Sturgis has con- several Cuban leaders from Fidel Castro fessed that he was involved in several CIA on down. assassination plots. The special commission headed by Vice But he has emphatically denied charges President Nelson Rockefeller is examin- that he was in Dallas on the day President ing "evidence" which allegedly links Stur- Kennedy was shot or that he had anything gis and Hunt to the Kennedy assassins: to do with the Kennedy assassination. Lion. The chief exhibit is a picture of two Sturgis offered to take a lie detector test vagrants, resembling Sturgis and Hunt, if the commission had any doubt that he who were picked up in Dallas after the. was telling the truth. No polygraph test; assassination. however, was administered. Upon close examination, the picture of Watergate conspirator E. -

THE TAKING of AMERICA, 1-2-3 by Richard E

THE TAKING OF AMERICA, 1-2-3 by Richard E. Sprague Richard E. Sprague 1976 Limited First Edition 1976 Revised Second Edition 1979 Updated Third Edition 1985 About the Author 2 Publisher's Word 3 Introduction 4 1. The Overview and the 1976 Election 5 2. The Power Control Group 8 3. You Can Fool the People 10 4. How It All BeganÐThe U-2 and the Bay of Pigs 18 5. The Assassination of John Kennedy 22 6. The Assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King and Lyndon B. Johnson's Withdrawal in 1968 34 7. The Control of the KennedysÐThreats & Chappaquiddick 37 8. 1972ÐMuskie, Wallace and McGovern 41 9. Control of the MediaÐ1967 to 1976 44 10. Techniques and Weapons and 100 Dead Conspirators and Witnesses 72 11. The Pardon and the Tapes 77 12. The Second Line of Defense and Cover-Ups in 1975-1976 84 13. The 1976 Election and Conspiracy Fever 88 14. Congress and the People 90 15. The Select Committee on Assassinations, The Intelligence Community and The News Media 93 16. 1984 Here We ComeÐ 110 17. The Final Cover-Up: How The CIA Controlled The House Select Committee on Assassinations 122 Appendix 133 -2- About the Author Richard E. Sprague is a pioneer in the ®eld of electronic computers and a leading American authority on Electronic Funds Transfer Systems (EFTS). Receiving his BSEE degreee from Purdue University in 1942, his computing career began when he was employed as an engineer for the computer group at Northrup Aircraft. He co-founded the Computer Research Corporation of Hawthorne, California in 1950, and by 1953, serving as Vice President of Sales, the company had sold more computers than any competitor. -

Watergate, Multiple Conspiracies, and the White House Tapes

Do Not Delete 8/1/2012 8:26 PM Watergate, Multiple Conspiracies, and the White House Tapes Arnold Rochvarg* On January 1, 1975, John Mitchell, former United States Attorney General, John Ehrlichman, former Chief White House Assistant for Domestic Affairs, H.R. Haldeman, former White House Chief of Staff, and Robert Mardian, former Assistant Attorney General, were convicted of conspiracy1 for their involvement in what is generally known as “Watergate.”2 The Watergate conspiracy trial, presided over by Judge John Sirica, had run from October 1, 1974 until December 27, 1974.3 The trial included the in-court testimony of most of the figures involved in the Watergate scandal,4 and the playing of thirty of the “White House tapes.”5 The purpose of this Symposium article is to discuss whether the evidence presented at the Watergate trial is better understood as evidence of multiple conspiracies, as argued by two of the defendants,6 or as a single conspiracy as argued by the prosecution. The article first will set forth the law on multiple conspiracies and apply that law to the evidence presented at the Watergate conspiracy trial. The article will then discuss whether the admission into evidence of certain White House tapes premised on the single conspiracy view may have prejudiced any of the convicted defendants. I. THE LAW OF MULTIPLE CONSPIRACIES It is not uncommon at a criminal conspiracy trial, or on appeal from a conviction of conspiracy, for a defendant to argue that a guilty verdict for * Professor, University of Baltimore School of Law. Professor Rochvarg was a member of the legal defense team that represented Robert Mardian in the appeal of his conviction of conspiracy at the Watergate conspiracy trial. -

'Whit Eid's Home Address in Telephone Number Is UN4-0400. P Ses

Gcd Page 2 CO-2-34030 magazine, that he had been approached with an Differ to purchase some confi- dential photographs of the assassination-of President Kennedy. These I photographs were pl)erred to show the large head/wounds with parts of the skull missing. Ruby unders oo• a t s o fer was made to Moss by either Attorney Tom Howard or his representative. No price was mentioned as to the cost of these photographs. Ruby said he understood that these photographs are apparently in the possession of law-enforcement officials in Dallas, but all evidence and photographs would become available to Howard for Jack Ruby's defense. Earl Ruby departed Los Angeles on December 3, 1963, and flew to Dallas where he conferred with his sister, Eva Grant, and his brother, Jack Ruby, concerning the forthcoming story. While in Dallas, Ruby said he talked to Tom Howard about these photographs, at which time Howard emphatically denied any knowledge concerning them. Ruby did not have 'Whit eId's home address in Angeles, but.--',Ke supplied his two telepho numbers, those being P0-3-39aTand TR4-4482. Shore resides at 199 N.'Almont Drive, Los Anaele:S748„-talifOrriia business phone HO b-82_11, and resident phone numbers BRJ:2-9836 and CR-41.0043. i Ruby said he would advise this office immediately if further detAil ,,n erning anyaspect of this case come to his attention. ,e-confidential source has advised that Detroit telephone number 3532:2730 was listed to Earl Rub untilNovember 25, 1963, at w4eK time his nuro-e.i was changed to 3533870. -

Character/Person Role/Job the PRESIDENT and ALL of HIS MEN

Actor Character/Person Role/Job THE PRESIDENT AND ALL OF HIS MEN Richard Nixon 37th US President 39th VP under Nixon until 1973; resigned amid charges of extortion, tax fraud, bribery & Spiro Agnew conspiracy (replaced by Gerald Ford, who was the House Minority Leader) VP replacing Agnew, later became 38th US Gerald Ford President Special counsel to Nixon; set up the Charles Colson "plumbers" unit to investigate info leaks from White House Nixon's domestic policy adviser; directed the John Ehrlichman "plumbers" unit H.R. “Bob” Haldeman Nixon’s chief of staff Haldeman's right-hand man; was the deputy Jeb Stuart Magruder director of Nixon's re-election campaign when the break-in occurred at his urging Nixon’s 1972 midwest campaign manager; Kenneth Dahlberg his check for $25k to Maurice Stans wound up in bank acct of a Watergate burglar Attorney General; then quit AG to be John Randolph John Mitchell chairman of CREEP; linked to a slush fund that funded the burglary Replaced Mitchell as chairman of CREEP Clark MacGregor (July to Nov 1972) Became Attorney General in 1972 (5 days before Watergate break-in) when Mitchell Richard Kleindienst resigned as AG to go work for CREEP; resigned in 1973 Former CIA agent and mastermind of the break-in; Member of the White House E. Howard Hunt "plumbers"; his phone # was found on a WG burglar, linking break-in to WH Former FBI agent who helped plan the break- G. Gordon Liddy in at DNC offices; spent over 4 years in prison; now an actor, author & talk-show host Commerce secretary & later the finance chairman for CREEP; raised nearly $60 Maurice Stans million for Nixon's re-election; insisted that he had no knowledge how some of the money he raised wound up in the cover-up. -

Rockefeller Commission Report - Final (4)” of the Richard B

The original documents are located in Box 8, folder “Intelligence - Rockefeller Commission Report - Final (4)” of the Richard B. Cheney Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 8 of the Richard B. Cheney Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library Chapter 16 Domestic Activities of the Directorate of Science and Technology In the past two decades, the CIA has placed increasing emphasis upon gathering foreign intelligence through technical and scientific means. In 1963, Director John McCone sought to coordinate the scientific development of intelligence devices and systems by creating the Science and Technology Directorate within the CIA. Most of the scientific and technological endeavors had been previously under taken by the Plans (now Operations) Directorate. The Science and Technology Directorate is presently rP.~_!)nm::ihlP. ior all ot the research and development engaged in by the CIA in all fields of science and technology. Projects range from complex satellite systems to the development of miniature cameras and concealed listening devices. -

Contents (Click on Index Item to Locate)

Contents (Click on index item to locate) Subject Page Foreword iii Introductory Note xi Statement of Information 1 Statement of Information and Supporting Evidence 69 As-- ~~ on y 35 780 0 STATEMENT O19 INFORMATION H E A R I N G S BEFORE THE COMMITTEE OWN THE JUDICIARY HOI:TSE OF REPRESENTATIVES NINETY-THIRD CONGRESS SECOND SESSION PIJR61JANT TO H. Res. 803 A RESOLUTION AUTHORIZING AND DIRECTING THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY TO INVESTIGATE WHETHER SUFFICIENT GROUNDS EXIST FOR THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES TO EXERCISE ITS CONSTITUTIONAL POWER TO IMPEACH RICHARD M. NIXON PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BOOK II EVENTS FOLLOWING THE WATERGATE BREAK-IN June 17,1972-February 9,1973 MAY—JUNE 1974 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1974 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. Price $6.10. COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY PETER W. RODINO, JO., New Jersey, Chairman HAROLD D. DONOHUE, Massachusetts EDWARD HUTCHINSON, Michigan JACK BROOKS, Texas ROBERT MCeLORY, Illinois ROBERT W. KASTENMEIER, Wisconsin HENRY P. SMITH III, New York DON EDWARDS, California CHARLES W. SANDMAN, Jo., New Jersey WILLIAM L. HUNGATE, Missouri ~~A. JOHN CONFERS, JR., Michigan JOSHUA EILBERG, Pennsylvania JEROME R. WALDIE, California WALTER FLOWERS, Alabama JAMES R. MANN, South Carolina PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland JOHN F. SEIBERLING, Ohio GEORGE E. DANIELSON, California ROBERT F. DRINAN, Massaehusetts CHARLES B. RANGEL, New York BARBARA JORDAN, Texas RAY THORNTON, Arkansas ELIZABETH HOLTZMAN, New York WAYNE OWENS, Utah EDWARD MEZVINSRY, Iowa TOM RAILS BACK, Illinois CHARLES E. WIGGINS, California DAVID W. DENNIS, Indiana HAMILTON FISH, JH., New York WILEY MAYNE, Iowa LAWRENCE J. -

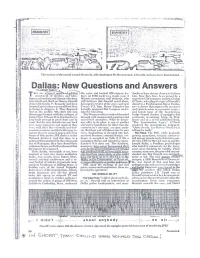

Dallas: New Questions and Answers

1,77 FRAME 312 1 4-043•Cri.. , • • 1-_ The mystery of the mortal wound: Kennelly, still clutching at his throat wound, is hit with explosive furl' from behind Dallas:c riEFR: New Questions and Answers are reed spa al odd-lot the cause and booked 250 campus lee- doubters have always chosen to believe T h"assortment n s critics ant dE-o-- hires (at $780 each) inn single year. A him. Now they have beenjoined by a logues, rationalists and funtasts who have Warren commission staff alumnus, who sometime CIA computer analyst, George never believed that Lee Harvey Oswald still believes that Oswald acted alone, O'Toole, who played a tape of Oswald's alone killed John F. Kennedy and have has urged a review of the case—and now denial to a Psychological Stress Evalua- invested up to a dozen years of their lives Texas's U.S. Rep. Henry Gonzalez has tor—a device that supposedly measures in hying to disprove it. They flowered formally proposed that Congress under- and charts tension in a person's voice— first in the middle '60s, then fell into take the rehearing. and found none of the bunched-up, discouraged retreat with the collapse of The Warren verdict is indeed threaded hedge-shaped clusters of squiggles that former New Orleans D.A. Jim Garrison's through with unanswered questions and (momently accompany lying. In Pent- jerry-built attempt to prove their case in unresolved anomalies. What its detrac- house and in a newly published book, court. But the true disbelievers are back tors offer in its place is one or another "The Assassination Tapes," O'Toole now, more numenms and insistent than aiterreiti-re hypothesis fin tidier than the rendered his unambig • jedgment: ever, with their duce-Oswald and four- cm lllll ission's one-man, one-gun analy- "Quite clearly, Lee Harvey Oswald was assassin scenarios and their dizzying ex- sis.