Dvoretsky Lessons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER 159 (June 05, 2014)

NEWSLETTER 159 (June 05, 2014) SILVIO DANAILOV, GARRY KASPAROV AND JORAN AULIN JANSSON – JJ TAKE PART IN THE OFFICIAL OPENING CEREMONY OF NO LOGO NORWAY CHESS TOURNAMENT The ECU President Silvio Danailov, the chess legend Garry Kasparov and the President of the Norwegian Chess Federation Joran Aulin Jansson - JJ took part in the official opening ceremony of No Logo Norway Chess Tournament which started on 2nd June in Stavanger and will end on 13th June, 2014. No Logo Norway Chess is the strongest chess tournament this year worldwide. On 3rd June the ECU President Silvio Danailov gave an interview for the Norwegian TV channel NRK TV. On 4th June Mr. Danailov officially opened the second round of the competition by making the first symbolic move in the game between Veselin Topalov and Alexander Grischuk. © Ecuonline.net Page 1 ECU President also took part in the live commentary together with GM Nigel Short and Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam. This year participants in the second edition of the tournament are: Magnus Carlsen, Levon Aronian, Alexander Grischuk, Fabiano Caruana, Vladimir Kramnik, Veselin Topalov, Sergey Karjakin, Peter Svidler, Anish Giri and Simen Agdestein. © Ecuonline.net Page 2 © Ecuonline.net Page 3 Standings after round 2 Rk. Name Pts. Berger Wins Black wins i-Ratingprest 1 GM Fabiano Caruana 2,0 1,50 2 1 3472 (+9,50) 2 GM Levon Aronian 1,5 1,00 1 0 2892 (+2,00) 3 GM Simen Agdestein 1,0 1,25 0 0 2783 (+4,10) 4 GM Magnus Carlsen 1,0 1,00 0 0 2767 (-3,00) 5 GM Anish Giri 1,0 1,00 0 0 2754 (-0,00) 6 GM Vladimir Kramnik 1,0 0,75 0 0 2817 (+0,90) 7 GM Alexander Grischuk 1,0 0,50 1 1 2781 (-0,30) 8 GM Peter Svidler 0,5 0,50 0 0 2594 (-4,10) 9 GM Sergey Karjakin 0,5 0,25 0 0 2600 (-4,40) 10 GM Veselin Topalov 0,5 0,25 0 0 2588 (-4,70) Official website: http://norwaychess.com CC ASHDOD ILIT WINS THE ISRAELI NATIONAL TEAM CHAMPIONSHIP 2014 CC Ashdod Ilit won the Israeli National Team Championship 2014 with 45 game points. -

Bulletin Round 6 -08.08.14

Bulletin Round 6 -08.08.14 That Carlsen black magic Blitz and “Media chess attention playing is a tool to seals get people to chess” Photos: Daniel Skog, COT 2014 (Carlsen and Seals) / David Martinez, chess24 (Gelfand) Chess Olympiad Tromsø 2014 – Bulletin Round 6– 08.08.14 Fabiano Caruana and Magnus Carlsen before the start of round 6 Photo: David Llada / COT2014 That Carlsen black magic Norway 1 entertained the home fans with a clean 3-1 over Italy, and with Magnus Carlsen performing some of his patented minimalist magic to defeat a major rival. GM Kjetil Lie put the Norwegians ahead with the kind of robust aggression typical of his best form on board four, and the teams traded wins on boards two and three. All eyes were fixed on the Caruana-Carlsen clash, where Magnus presumably pulled off an opening surprise by adopting the offbeat variation that he himself had faced as White against Nikola Djukic of Montenegro in round three. By GM Jonathan Tisdall Caruana appeared to gain a small but comfortable Caruana is number 3 in the world and someone advantage in a queenless middlegame, but as I've lost against a few times, so it feels incredibly Carlsen has shown so many times before, the good to beat him. quieter the position, the deadlier he is. In typically hypnotic fashion, the position steadily swung On top board Azerbaijan continues to set the Carlsen's way, and suddenly all of White's pawns pace, clinching another match victory thanks to were falling like overripe fruit. Carlsen's pleasure two wins with the white pieces, Mamedyarov with today's work was obvious, as he stopped to beating Jobava in a bare-knuckle brawl, and with high-five colleague Jon Ludvig Hammer on his GM Rauf Mamedov nailing GM Gaioz Nigalidze way into the NRK TV studio. -

Weltenfern a Commented Selection of Some of My Works Containing 149 Originals

Weltenfern A commented selection of some of my works containing 149 originals by Siegfried Hornecker Dedicated to the memory of Dan Meinking and Milan Velimirovi ć who both encouraged me to write a book! Weltenfern : German for other-worldly , literally distant from the world , describing a person’s attitude In the opinion of the author the perfect state of mind to compose chess problems. - 1 - Index 1 – Weltenfern 2 – Index 3 – Legal Information 4 – Preface 6 – 20 ideas and themes 6 – Chapter One: A first walk in the park 8 – Chapter Two: Schachstrategie 9 – Chapter Three: An anticipated study 11 – Chapter Four: Sleepless nights, or how pain was turned into beauty 13 – Chapter Five: Knightmares 15 – Chapter Six: Saavedra 17 – Chapter Seven: Volpert, Zatulovskaya and an incredible pawn endgame 21 – Chapter Eight: My home is my castle, but I can’t castle 27 – Intermezzo: Orthodox problems 31 – Chapter Nine: Cooperation 35 – Chapter Ten: Flourish, Knightingale 38 – Chapter Eleven: Endgames 42 – Chapter Twelve: MatPlus 53 – Chapter 13: Problem Paradise and NONA 56 – Chapter 14: Knight Rush 62 – Chapter 15: An idea of symmetry and an Indian mystery 67 – Information: Logic and purity of aim (economy of aim) 72 – Chapter 16: Make the piece go away 77 – Chapter 17: Failure of the attack and the romantic chess as we knew it 82 – Chapter 18: Positional draw (what is it, anyway?) 86 – Chapter 19: Battle for the promotion 91 – Chapter 20: Book Ends 93 – Dessert: Heterodox problems 97 – Appendix: The simple things in life 148 – Epilogue 149 – Thanks 150 – Author index 152 – Bibliography 154 – License - 2 - Legal Information Partial reprint only with permission. -

The Day of Miracles. Kramnik Took the Lead. Prestige Goal by Ivanchuk. This

The day of miracles. Kramnik took the lead. Prestige goal by Ivanchuk. This are not the whole list of headlines after round 12 in Candidates Tournament in London. Long Friday was really long Friday. For the first time in the tournament absolutely all games finished after first time control and 40 moves. Today I will continue with ecologically clean annotations (Totally without computer analyzes) “online” comments by IM &FT Vladimir Poley. Text of the games you can find on organisers home page. Pairs of the day: Magnus Carlsen –Vasily Ivanchuk Levon Aroian – Vladimir Kramnik Teimour Radjabov – Alexander Grischuk Boris Gelfand-Peter Svidler Magnus avoid Rossolimo today and said straight no to Cheljabinsk (Sveshnikov) variation by 3.Nc3. Vasily after 5 minutes thought decided to transfer his Sicilian defense into Taimanov variation, old and solid version. Alternative was 3...e5, but this can lead after transformation into “The Spanish torture” where Magnus feels like fish in the water. Kramnik chosen improved Tarrash defense against Aronian. The difference from normal Tarrash- is no isolated pawn on d5. Radjabov-Grischuk- easy going with draw reputation Queens Gambit variation, probably quickpeace agreement. Both players lost chances and not enough motivated. Gelfand plays anti-Grunfeld variation. To go into the main lines against biggest Grunfeld expert Svidler was not an option. Boris will look for fishy on sides. Grischuk invites to some pawns capture for advantage in development in return and started to shake the boat. I don’t believe that Teimour will accept the gifts. Just normal Nf3 will be good neutral response. Aronian decided to get isolany himself. -

Dvoretsky Lessons 12

The Instructor Tragicomedies in Pawn Endgames “Pawn endgames are rare birds in practice. Players avoid them, because they do not like them, because they do not understand them. It’s certainly no secret that pawn endings are ‘terra incognita’ - even for many masters, right up to the level of grandmasters and world champions.” N. Grigoriev Herewith, I offer proof that these words, spoken by a famous expert on pawn endings, are true. Without commentary, I give below the final moves of some actual games, and offer the readers the chance to comment on them, to uncover all the mistakes committed by both players. The endgames you will be dealing with here are not all that difficult; but still, the players on both sides have The provided you with plenty of opportunities for critical commentary. 1...Kf8 2. Qf5+ Qxf5 3. gf Kg7 4. c4 f3 5. h6+ Kxh6 6. c5 dc 7. f6 Kg6 Instructor White resigned. Mark Dvoretsky 1...g5 2. Kf3 Kd5 3. c6 Kd6 4. Ke4 a6 5. ba Kxc6 6. Kf3 Kb6 7. h4 gh 8. Kg4 Kxa6 9. Kxh4 Kb6 10. Kg4 Kc6 11. h4 Kd6. White resigned. file:///C|/Cafe/Dvoretsky/dvoretsky.htm (1 of 9) [9/11/2001 7:09:02 AM] The Instructor 1. Kh7 Kf7 2. Kh8 Kf8 3. g5. Black resigned. 1. Kg5 Kf8 2. Kxf5 Kf7 3. Kg4 Kf6 4. Kf4 Kf7 5. Kf5 Ke7 6. Ke5 Kf7 7. Kd6 Kf6 8. Kd7 Kf7 9. h6 Kg6 10. f4 Kf7 11. f5 Kf6 Drawn Gazic - Petursson European Junior Championship, Groningen 1978/79 The draw is obvious after 1...Kh8! Black mistakenly allowed the trade of queens. -

Play for Russia Charity Online Tournament

Play For Russia Charity Online Tournament Round 1, 12.05.2020 № Title Name Rating Result Title Name Rating № 1 GM Vladimir Kramnik 2797 - GM Alexander Riazantsev 2497 8 2 GM Ian Nepomniachtchi 2785 - GM Ernesto Inarkiev 2639 7 3 GM Sergey Karjakin 2766 - GM Evgeny Tomashevsky 2695 6 4 GM Alexander Grischuk 2765 - GM Peter Svidler 2754 5 Round 2, 12.05.2020 № Title Name Rating Result Title Name Rating № 8 GM Alexander Riazantsev 2497 - GM Peter Svidler 2754 5 6 GM Evgeny Tomashevsky 2695 - GM Alexander Grischuk 2765 4 7 GM Ernesto Inarkiev 2639 - GM Sergey Karjakin 2766 3 1 GM Vladimir Kramnik 2797 - GM Ian Nepomniachtchi 2785 2 Round 3, 12.05.2020 № Title Name Rating Result Title Name Rating № 2 GM Ian Nepomniachtchi 2785 - GM Alexander Riazantsev 2497 8 3 GM Sergey Karjakin 2766 - GM Vladimir Kramnik 2797 1 4 GM Alexander Grischuk 2765 - GM Ernesto Inarkiev 2639 7 5 GM Peter Svidler 2754 - GM Evgeny Tomashevsky 2695 6 Round 4, 12.05.2020 № Title Name Rating Result Title Name Rating № 8 GM Alexander Riazantsev 2497 - GM Evgeny Tomashevsky 2695 6 7 GM Ernesto Inarkiev 2639 - GM Peter Svidler 2754 5 1 GM Vladimir Kramnik 2797 - GM Alexander Grischuk 2765 4 2 GM Ian Nepomniachtchi 2785 - GM Sergey Karjakin 2766 3 Round 5, 12.05.2020 № Title Name Rating Result Title Name Rating № 3 GM Sergey Karjakin 2766 - GM Alexander Riazantsev 2497 8 4 GM Alexander Grischuk 2765 - GM Ian Nepomniachtchi 2785 2 5 GM Peter Svidler 2754 - GM Vladimir Kramnik 2797 1 6 GM Evgeny Tomashevsky 2695 - GM Ernesto Inarkiev 2639 7 Round 6, 12.05.2020 № Title Name -

Sample Pages

Dvoretsky’s Analytical Manual by Mark Dvoretsky Foreword by Karsten Müller 2013 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 Dvoretsky’s Analytical Manual © Copyright 2008, 2013 Mark Dvoretsky All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. ISBN: 978-1-936490-74-5 First Edition 2008 Second Edition 2013 Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Cover design by Janel Lowrance Translated from the Russian by Jim Marfia Photograph of Mark Dvoretsky by Carl G. Russell Printed in the United States of America 2 Table of Contents Foreword 4 Introduction 5 Signs, Symbols, and Abbreviations 10 Part 1 Immersion in the Position 11 Chapter 1 Combinative Fireworks 12 Chapter 2 Chess Botany – The Trunk 25 Chapter 3 Chess Botany – The Shrub 32 Chapter 4 Chess Botany – Variational Debris 38 Chapter 5 Irrational Complications 49 Chapter 6 Surprises in Calculating Variations 61 Chapter 7 More Surprises in Calculating Variations 69 Part 2 Analyzing the Endgame 85 Chapter 8 Two Computer Analyses 86 Chapter 9 Zwischenzugs in the Endgame 93 Chapter 10 Play like a Computer 98 Chapter 11 Challenging Studies 106 Chapter 12 Studies for Practical -

The Queen's Gambit

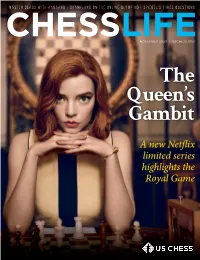

Master Class with Aagaard | Shankland on the Online Olympiad | Spiegel’s Three Questions NOVEMBER 2020 | USCHESS.ORG The Queen’s Gambit A new Netflix limited series highlights the Royal Game The United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer 888.51.CHESS (512.4377) www.USCFSales.com EXCHANGE OR NOT UNIVERSAL CHESS TRAINING by Eduardas Rozentalis by Wojciech Moranda B0086TH - $33.95 B0085TH - $39.95 The author of this book has turned his attention towards the best Are you struggling with your chess development? While tool for chess improvement: test your current knowledge! Our dedicating hours and hours on improving your craft, your rating author has provided the most important key elements to practice simply does not want to move upwards. No worries ‒ this book one of the most difficult decisions: exchange or not! With most is a game changer! The author has identified the key skills that competitive games nowadays being played to a finish in a single will enhance the progress of just about any player rated between session, this knowledge may prove invaluable over the board. His 1600 and 2500. Becoming a strong chess thinker is namely brand new coverage is the best tool for anyone looking to improve not only reserved exclusively for elite players, but actually his insights or can be used as perfect teaching material. constitutes the cornerstone of chess training. THE LENINGRAD DUTCH PETROSIAN YEAR BY YEAR - VOLUME 1 (1942-1962) by Vladimir Malaniuk & Petr Marusenko by Tibor Karolyi & Tigran Gyozalyan B0105EU - $33.95 B0033ER - $34.95 GM Vladimir Malaniuk has been the main driving force behind International Master Tibor Karolyi and FIDE Master Tigran the Leningrad Variation for decades. -

Dvoretsky's Endgame Manual

Dvoretsky’s Endgame Manual Mark Dvoretsky Foreword by Artur Yusupov Preface by Jacob Aagaard 2003 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 Table of Contents Foreword 6 Preface 7 From the Author 8 Other Signs, Symbols, and Abbreviations 12 Chapter 1 PAWN ENDGAMES 13 Key Squares 13 Corresponding Squares 14 Opposition 14 Mined Squares 18 Triangulation 20 Other Cases of Correspondence 22 King vs. Passed Pawns 24 The Rule of the Square 24 Réti’s Idea 25 The Floating Square 27 Three Connected Pawns 28 Queen vs. Pawns 29 Knight or Center Pawn 29 Rook or Bishop’s Pawn 30 Pawn Races 32 The Active King 34 Zugzwang 34 Widening the Beachhead 35 The King Routes 37 Zigzag 37 The Pendulum 38 Shouldering 38 Breakthrough 40 The Outside Passed Pawn 44 Two Rook’s Pawns with an Extra Pawn on the Opposite Wing 45 The Protected Passed Pawn 50 Two Pawns to One 50 Multi-Pawn Endgames 50 Undermining 53 Two Connected Passed Pawns 54 Stalemate 55 The Stalemate Refuge 55 “Semi-Stalemate” 56 Reserve Tempi 57 Exploiting Reserve Tempi 57 Steinitz’s Rule 59 The g- and h-Pawns vs. h-Pawn 60 The f- and h-Pawns vs. h-Pawn 62 Both Sides have Reserve Tempi 65 Chapter 2 KNIGHT VS. PAWNS 67 1 King in the Corner 67 Mate 67 Drawn Positions 67 Knight vs. Rook Pawn 68 The Knight Defends the Pawn 70 Chapter 3 KNIGHT ENDGAMES 74 The Deflecting Knight Sacrifice 74 Botvinnik’s Formula 75 Pawns on the Same Side 79 Chapter 4 BISHOP VS. -

The World Fischer Random Chess Championship Is Now Officially Recognized by FIDE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Oslo, April 20, 2019. The World Fischer Random Chess Championship is now officially recognized by FIDE This historic event will feature an online qualifying phase on Chess.com, beginning April 28, and is open to all players. The finals will be held in Norway this fall, with a prize fund of $375,000 USD. The International Chess Federation (FIDE) has granted the rights to host the inaugural FIDE World Fischer Random Chess Championship cycle to Dund AS, in partnership with Chess.com. And, for the first time in history, a chess world championship cycle will combine an online, open qualifier and worldwide participation with physical finals. “With FIDE’s support for Fischer Random Chess, we are happy to invite you to join the quest to become the first-ever FIDE World Fischer Random Chess Champion” said Arne Horvei, founding partner in Dund AS. “Anyone can participate online, and we are excited to see if there are any diamonds in the rough out there that could excel in this format of chess,” he said. "It is an unprecedented move that the International Chess Federation recognizes a new variety of chess, so this was a decision that required to be carefully thought out,” said FIDE president Arkady Dvorkovich, who recently visited Oslo to discuss this agreement. “But we believe that Fischer Random is a positive innovation: It injects new energies an enthusiasm into our game, but at the same time it doesn't mean a rupture with our classical chess and its tradition. It is probably for this reason that Fischer Random chess has won the favor of the chess community, including the top players and the world champion himself. -

Møt Spillerne I Altibox Norway Chess Side 20–22

AVIS FOR SUPERTURNERINGEN I SJAKK ALTIBOX STAVAngerregionen 3.–15. juni NORWAY CHess MAGNUS CARLSEN NORGE MAXIME VACHIER- SHAKHRIYAR MAMEDYAROV VISWANATHAN ANAND LAGRAVE FRANKRIKE ASERBAJDSJAN INDIA DING LIREN LEVON ARONIAN FABIANO CARUANA KINA ARMENIA USA WESLEY SO YANGYI YU ALEXANDER GRISCHUK USA KINA RUSSLAND Møt spillerne i Altibox Norway Chess Side 20–22 En annerledes skole- Ekslusivt intervju med Lynkurs i sjakk med sjakkturnering SIDE 16 Siri Lill Mannes SIDE 24 Ellisiv Reppen SIDE 29 2 ALTIBOX NORWAY CHESS 3.–15. JUNI 2019 INNHOLD PLANT ET TRE GI EN BEDRE FREMTID Leder ......................................... 03 Produksjon av arganolje Program ..................................... 04 er en av svært få muligheter for betalt Et tilbakeblikk på fjorårets arbeid for fattige kvinner i sørvest turnering .................................... 06 Marokko. Argan skogen er også helt essensiell for dyre- og plantelivet i Tiden – et viktig element i sjakk 13 landet, og har så stor betydning for klima De første sjakkstjernene ........... 14 at UNESCO erklærte den et biosfærereservat i 1998. Skolesjakkturneringen .............. 16 Spill gjennom alle tider ............. 19 Nå er skogen utrydningstruet! Møt spillerne .............................. 20 Intervju med Siri Lill Mannes .... 24 Kompleksiteten i det oversiktlige................................. 27 Lynkurs i sjakk ........................... 29 Argan skogen i Marokko er avgjørende for Carlsens ofre ............................. 31 tusenvis av plante- og dyrearter og helt essensiell Argan Care ble startet av Benedicte Westre Skog i Stavanger i 2016. Vi har så langt plantet og for å redusere spredning av ørkenen i området. Dronning Shakiras hevn ............ 32 Skogen har blitt redusert kraftig de siste årene på rehabilitert trær på 200 mål sør-vest i Marokko. grunn av overforbruk, avskoging og kanskje noe Argan Care bidrar til å etablere arbeidsplasser, Løpsk løper mot spesielt for kvinner, i en region med svært få mer overraskende, geiter. -

London Chess Classic Day 3 Round-Up

6th December 2015 LONDON CHESS CLASSIC DAY 3 ROUND-UP After yesterday’s five draws, it looked like there could be up to four decisive results in today’s 3rd round, but many missed opportunities meant Maxime Vachier-Lagrave was the only player to bring home the full point, thus joining Anish Giri in the lead with 2/3. World Champion Magnus Carlsen facing his predecessor Vishy Anand In the most highly anticipated clash of the day, Carlsen chose to meet Anand’s Ruy Lopez with the Berlin Defence, an opening that famously played a huge part in both their World Championship matches. Anand came out of the opening with a favourable position, but a few inaccuracies before the time control left Carlsen in the driving seat. However, the World Champion failed to convert his clear advantage and the players eventually agreed a draw on move 57. Carlsen was clearly displeased after the game, stating: ‘It was a bit embarrassing for both of us’. Another player who came very close to tasting victory was Alexander Grischuk. The Russian virtuoso spent 1 hour and 3 minutes(!) on 20.f4, but subsequently reached an almost winning position. Having run very short of time though, he missed the necessary precision to convert his advantage and a draw was agreed – meaning Anish Giri remains unbeaten in the Grand Chess Tour. Caruana will also be disappointed tonight, as he failed to convert a position that seemed to be technically winning in the US derby against Nakamura. Adams meanwhile scored his third draw - against Aronian - despite having been a tiny bit worse out of the opening.