Design and Development of a BANG-File Clustering System“

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effect of Distance Measures on Partitional Clustering Algorithms

Sesham Anand et al, / (IJCSIT) International Journal of Computer Science and Information Technologies, Vol. 6 (6) , 2015, 5308-5312 Effect of Distance measures on Partitional Clustering Algorithms using Transportation Data Sesham Anand#1, P Padmanabham*2, A Govardhan#3 #1Dept of CSE,M.V.S.R Engg College, Hyderabad, India *2Director, Bharath Group of Institutions, BIET, Hyderabad, India #3Dept of CSE, SIT, JNTU Hyderabad, India Abstract— Similarity/dissimilarity measures in clustering research of algorithms, with an emphasis on unsupervised algorithms play an important role in grouping data and methods in cluster analysis and outlier detection[1]. High finding out how well the data differ with each other. The performance is achieved by using many data index importance of clustering algorithms in transportation data has structures such as the R*-trees.ELKI is designed to be easy been illustrated in previous research. This paper compares the to extend for researchers in data mining particularly in effect of different distance/similarity measures on a partitional clustering algorithm kmedoid(PAM) using transportation clustering domain. ELKI provides a large collection of dataset. A recently developed data mining open source highly parameterizable algorithms, in order to allow easy software ELKI has been used and results illustrated. and fair evaluation and benchmarking of algorithms[1]. Data mining research usually leads to many algorithms Keywords— clustering, transportation Data, partitional for similar kind of tasks. If a comparison is to be made algorithms, cluster validity, distance measures between these algorithms.In ELKI, data mining algorithms and data management tasks are separated and allow for an I. INTRODUCTION independent evaluation. -

BETULA: Numerically Stable CF-Trees for BIRCH Clustering?

BETULA: Numerically Stable CF-Trees for BIRCH Clustering? Andreas Lang[0000−0003−3212−5548] and Erich Schubert[0000−0001−9143−4880] TU Dortmund University, Dortmund, Germany fandreas.lang,[email protected] Abstract. BIRCH clustering is a widely known approach for clustering, that has influenced much subsequent research and commercial products. The key contribution of BIRCH is the Clustering Feature tree (CF-Tree), which is a compressed representation of the input data. As new data arrives, the tree is eventually rebuilt to increase the compression. After- ward, the leaves of the tree are used for clustering. Because of the data compression, this method is very scalable. The idea has been adopted for example for k-means, data stream, and density-based clustering. Clustering features used by BIRCH are simple summary statistics that can easily be updated with new data: the number of points, the linear sums, and the sum of squared values. Unfortunately, how the sum of squares is then used in BIRCH is prone to catastrophic cancellation. We introduce a replacement cluster feature that does not have this nu- meric problem, that is not much more expensive to maintain, and which makes many computations simpler and hence more efficient. These clus- ter features can also easily be used in other work derived from BIRCH, such as algorithms for streaming data. In the experiments, we demon- strate the numerical problem and compare the performance of the orig- inal algorithm compared to the improved cluster features. 1 Introduction The BIRCH algorithm [23,24,22] is a widely known cluster analysis approach, that won the 2006 SIGMOD Test of Time Award. -

Research Techniques in Network and Information Technologies, February

Tools to support research M. Antonia Huertas Sánchez PID_00185350 CC-BY-SA • PID_00185350 Tools to support research The texts and images contained in this publication are subject -except where indicated to the contrary- to an Attribution- ShareAlike license (BY-SA) v.3.0 Spain by Creative Commons. This work can be modified, reproduced, distributed and publicly disseminated as long as the author and the source are quoted (FUOC. Fundació per a la Universitat Oberta de Catalunya), and as long as the derived work is subject to the same license as the original material. The full terms of the license can be viewed at http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/es/legalcode.ca CC-BY-SA • PID_00185350 Tools to support research Index Introduction............................................................................................... 5 Objectives..................................................................................................... 6 1. Management........................................................................................ 7 1.1. Databases search engine ............................................................. 7 1.2. Reference and bibliography management tools ......................... 18 1.3. Tools for the management of research projects .......................... 26 2. Data Analysis....................................................................................... 31 2.1. Tools for quantitative analysis and statistics software packages ...................................................................................... -

Machine Learning for Improved Data Analysis of Biological Aerosol Using the WIBS

Atmos. Meas. Tech., 11, 6203–6230, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-11-6203-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Machine learning for improved data analysis of biological aerosol using the WIBS Simon Ruske1, David O. Topping1, Virginia E. Foot2, Andrew P. Morse3, and Martin W. Gallagher1 1Centre of Atmospheric Science, SEES, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK 2Defence, Science and Technology Laboratory, Porton Down, Salisbury, UK 3Department of Geography and Planning, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK Correspondence: Simon Ruske ([email protected]) Received: 19 April 2018 – Discussion started: 18 June 2018 Revised: 15 October 2018 – Accepted: 26 October 2018 – Published: 19 November 2018 Abstract. Primary biological aerosol including bacteria, fun- The lowest classification errors were obtained using gra- gal spores and pollen have important implications for public dient boosting, where the misclassification rate was between health and the environment. Such particles may have differ- 4.38 % and 5.42 %. The largest contribution to the error, in ent concentrations of chemical fluorophores and will respond the case of the higher misclassification rate, was the pollen differently in the presence of ultraviolet light, potentially al- samples where 28.5 % of the samples were incorrectly clas- lowing for different types of biological aerosol to be dis- sified as fungal spores. The technique was robust to changes criminated. Development of ultraviolet light induced fluores- in data preparation provided a fluorescent threshold was ap- cence (UV-LIF) instruments such as the Wideband Integrated plied to the data. Bioaerosol Sensor (WIBS) has allowed for size, morphology In the event that laboratory training data are unavailable, and fluorescence measurements to be collected in real-time. -

Principal Component Analysis

02.01.2019 Prncpal component analyss - Wkpeda Principal component analysis Principal component analysis (PCA) is a statistical procedure that uses an orthogonal transformation to convert a set of observations of possibly correlated variables (entities each of which takes on various numerical values) into a set of values of linearly uncorrelated variables called principal components. If there are observations with variables, then the number of distinct principal components is . This transformation is defined in such a way that the first principal component has the largest possible variance (that is, accounts for as much of the variability in the data as possible), and each succeeding component in turn has the highest variance possible under the constraint that it is orthogonal to the preceding components. The resulting vectors (each being a linear combination of the variables and containing n PCA of a multivariate Gaussian observations) are an uncorrelated orthogonal basis set. PCA is sensitive to distribution centered at (1,3) with a the relative scaling of the original variables. standard deviation of 3 in roughly the (0.866, 0.5) direction and of 1 in PCA was invented in 1901 by Karl Pearson,[1] as an analogue of the the orthogonal direction. The principal axis theorem in mechanics; it was later independently developed vectors shown are the eigenvectors of the covariance matrix scaled by and named by Harold Hotelling in the 1930s.[2] Depending on the field of the square root of the corresponding application, it is also named the discrete Karhunen–Loève transform eigenvalue, and shifted so their tails (KLT) in signal processing, the Hotelling transform in multivariate quality are at the mean. -

A Study on Adoption of Data Mining Tools and Collision of Predictive Techniques

ISSN(Online): 2319-8753 ISSN (Print): 2347-6710 International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering and Technology (An ISO 3297: 2007 Certified Organization) Website: www.ijirset.com Vol. 6, Issue 8, August 2017 A Study on Adoption of Data Mining Tools and Collision of Predictive Techniques Lavanya.M1, Dr.B.Jagadhesan2 M.Phil Research Scholar, Dhanraj Baid Jain College (Autonomous), Thoraipakkam, Chennai, India1 Associate Professor, Dhanraj Baid Jain College (Autonomous), Thoraipakkam, Chennai, India2 ABSTRACT: Data mining, also known as knowledge discovery from databases, is a process of mining and analysing enormous amounts of data and extracting information from it. Data mining can quickly answer business questions that would have otherwise consumed a lot of time. Some of its applications include market segmentation – like identifying characteristics of a customer buying a certain product from a certain brand, fraud detection – identifying transaction patterns that could probably result in an online fraud, and market based and trend analysis – what products or services are always purchased together, etc. This article focuses on the various open source options available and their significance in different contexts. KEYWORDS: Data Mining, Clustering, Mining Tools. I. INTRODUCTION The development and application of data mining algorithms requires the use of powerful software tools. As the number of available tools continues to grow, the choice of the most suitable tool becomes increasingly difficult. Some of the common mining tasks are as follows. • Data Cleaning − The noise and inconsistent data is removed. • Data Integration − Multiple data sources are combined. • Data Selection − Data relevant to the analysis task are retrieved from the database. -

A Comparative Study on Various Data Mining Tools for Intrusion Detection

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 9, Issue 5, May-2018 1 ISSN 2229-5518 A Comparative Study on Various Data Mining Tools for Intrusion Detection 1Prithvi Bisht, 2Neeraj Negi, 3Preeti Mishra, 4Pushpanjali Chauhan Department of Computer Science and Engineering Graphic Era University, Dehradun Email: {1prithvisbisht, 2neeraj.negi174, 3dr.preetimishranit, 4pushpanajlichauhan}@gmail.com Abstract—Internet world is expanding day by day and so are the threats related to it. Nowadays, cyber attacks are happening more frequently than a decade before. Intrusion detection is one of the most popular research area which provides various security tools and techniques to detect cyber attacks. There are many ways to detect anomaly in any system but the most flexible and efficient way is through data mining. Data mining tools provide various machine learning algorithms which are helpful for implementing machine- learning based IDS. In this paper, we have done a comparative study of various state of the art data mining tools such as RapidMiner, WEKA, EOA, Scikit-Learn, Shogun, MATLAB, R, TensorFlow, etc for intrusion detection. The specific characteristics of individual tool are discussed along with its pros & cons. These tools can be used to implement data mining based intrusion detection techniques. A preliminary result analysis of three different data-mining tools is carried out using KDD’ 99 attack dataset and results seem to be promising. Keywords: Data mining, Data mining tools, WEKA, RapidMiner, Orange, KNIME, MOA, ELKI, Shogun, R, Scikit-Learn, Matlab —————————— —————————— 1. Introduction These patterns can help in differentiating between regular activity and malicious activity. Machine-learning based IDS We are living in the modern era of Information technology where most of the things have been automated and processed through computers. -

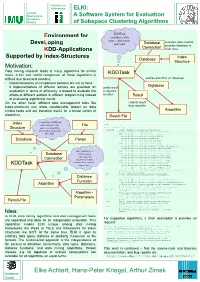

ELKI: ELKI: ELKI: a Software System for Evaluation a Software System

Institute for Informatics ELKI: Ludwig- Maximilians- A Software System for Evaluation Universityy Munich of Subspace Clustering Algorithms KDDTKDDTask k Environment for coordinates data source,,pp application,li i , manages data readingreading, DeveLoping and result. result DtbDatabase CtiConnection provides database to KDD-Applications main class Supported by Indendex-StrStructures ct res Index Database Structure Motivation: DtDataata miningiig researchesea ch ldleadseads tto manyayalgorithmsagolith t s fforo similarsaiil tktasks. A fifair andd usefulflcomparisonp i off ththese algorithmslithg iis KDDTask difficult due to several reasons: applies algorithm on database • Implementations of comparison partners are not at hand. Database • If implementations of different authors are providedprovided, an prints result evaluation in terms of efficiency is biased to evaluate the to desired effortseosff t ofof diffdifferentdee t authorsauth o s iin efficienteceffi i t programmingpogai gitdinsteads ead location RltResult off evaluatingltig algorithmiclithig meritsit . On the other handhand, efficient data management tools like collects result index-structures can show considerable impact on data flithfrom algorithmg mining tasks and are therefore useful for a broad variety of Algorithmg algorithms. Result-File IdIndex Central class KDDTask gets assignedidd a data File USAGEUSAGE: StStructure t source, an algorithm, javaj de.lmu.ifi.dbs.elki.KDDTask -algorithm : <class> Classname of an algorithm (implementing and a target address for de.lmu.ifi.dbs.elki.algorithm.Algorithm -

Spca Assisted Correlation Clustering of Hyperspectral Imagery

ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume II-8, 2014 ISPRS Technical Commission VIII Symposium, 09 – 12 December 2014, Hyderabad, India SPCA ASSISTED CORRELATION CLUSTERING OF HYPERSPECTRAL IMAGERY A. Mehta a,*, O. Dikshit a a Department of Civil Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur, Kanpur – 208016, Uttar Pradesh, India [email protected], [email protected] KEY WORDS: Hyperspectral Imagery, Correlation Clustering, ORCLUS, PCA, Segmented PCA ABSTRACT: In this study, correlation clustering is introduced to hyperspectral imagery for unsupervised classification. The main advantage of correlation clustering lies in its ability to simultaneously perform feature reduction and clustering. This algorithm also allows selection of different sets of features for different clusters. This framework provides an effective way to address the issues associated with the high dimensionality of the data. ORCLUS, a correlation clustering algorithm, is implemented and enhanced by making use of segmented principal component analysis (SPCA) instead of principal component analysis (PCA). Further, original implementation of ORCLUS makes use of eigenvectors corresponding to smallest eigenvalues whereas in this study eigenvectors corresponding to maximum eigenvalues are used, as traditionally done when PCA is used as feature reduction tool. Experiments are conducted on three real hyperspectral images. Preliminary analysis of algorithms on real hyperspectral imagery shows ORCLUS is able to produce acceptable results. 1. INTRODUCTION cluster, subset of dimension (or subspace) may differ, in which cluster are discernible. Thus, it may be difficult for global In recent years, hyperspectral imaging has become an important feature reduction methods (e.g. principal component analysis) tool for information extraction, especially in the remote sensing to identify one common subspace in which all the cluster will community (Villa et al., 2013). -

275: Robust Principal Component Analysis for Generalized Multi-View

Robust Principal Component Analysis for Generalized Multi-View Models Frank Nussbaum1,2 Joachim Giesen1 1Friedrich-Schiller-Universität, Jena, Germany 2DLR Institute of Data Science, Jena, Germany Abstract where k · k is some suitable norm. The classical and still popular choice, see Hotelling [1933], Eckart and Young [1936], uses the Frobenius norm k · kF, which It has long been known that principal com- renders the optimization problem tractable. The Frobe- ponent analysis (PCA) is not robust with re- nius norm does not perform well though for grossly spect to gross data corruption. This has been corrupted data. A single grossly corrupted entry in X addressed by robust principal component can change the estimated low-rank matrix L signif- analysis (RPCA). The first computationally icantly, that is, the Frobenius norm approach is not tractable definition of RPCA decomposes a robust against data corruption. An obvious remedy is data matrix into a low-rank and a sparse com- replacing the Frobenius norm by the `1-norm k · k1, but ponent. The low-rank component represents this renders the optimization problem intractable be- the principal components, while the sparse cause of the non-convex rank constraint. Alternatively, component accounts for the data corruption. we can explicitly model a component that captures Previous works consider the corruption of data corruption. This leads to a decomposition individual entries or whole columns of the data matrix. In contrast, we consider a more X = L + S general form of data corruption that affects of the data matrix into a low-rank component L as groups of measurements. We show that the de- before and a matrix S of outliers. -

Statistically Rigorous Testing of Clustering Implementations

Statistically Rigorous Testing of Clustering Implementations Xin Yin Vincenzo Musco Iulian Neamtiu Usman Roshan Department of Computer Science New Jersey Institute of Technology Newark, NJ, USA fxy258, vincenzo.a.musco, ineamtiu, [email protected] Abstract—Clustering is a widely used AI technique, but defin- propose an approach that can expose substantial and system- ing clustering correctness, as well as verifying and validating clus- atic issues with clustering algorithms’ actual implementations, tering implementations, remains a challenge. To address this, we e.g., wide variations across runs for theoretically-stable, deter- propose a statistically rigorous approach that couples differential clustering with statistical hypothesis testing, namely we conduct ministic algorithms, widely different outcomes for different statistical hypothesis testing on the outcome (distribution) of implementations of the same algorithm, or consistently poor differential clustering to reveal problematic outcomes. performance in specific implementations. We employed this approach on widely-used clustering algo- Our approach leverages the wide availability of clustering rithms implemented in popular ML toolkits; the toolkits were implementations and datasets with ground truth, coupled with tasked with clustering datasets from the Penn Machine Learning a statistics-driven approach to help developers (or toolkit Benchmark. The results indicate that there are statistically signif- icant differences in clustering outcomes in a variety of scenarios testers) find statistically -

Machine-Learning

machine-learning #machine- learning Table of Contents About 1 Chapter 1: Getting started with machine-learning 2 Remarks 2 Examples 2 Installation or Setup using Python 2 Installation or Setup using R Language 5 Chapter 2: An introduction to Classificiation: Generating several models using Weka 7 Introduction 7 Examples 7 Getting started: Loading a dataset from file 7 Train the first classifier: Setting a baseline with ZeroR 8 Getting a feel for the data. Training Naive Bayes and kNN 9 Putting it together: Training a tree 11 Chapter 3: Deep Learning 13 Introduction 13 Examples 13 Short brief of Deep learning 13 Chapter 4: Evaluation Metrics 18 Examples 18 Area Under the Curve of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC) 18 Overview – Abbreviations 18 Interpreting the AUROC 18 Computing the AUROC 19 Confusion Matrix 21 ROC curves 22 Chapter 5: Getting started with Machine Learning using Apache spark MLib 24 Introduction 24 Remarks 24 Examples 24 Write your first classification problem using Logistic Regression model 24 Chapter 6: Machine learning and it's classification 28 Examples 28 What is machine learning ? 28 What is supervised learning ? 28 What is unsupervised learning ? 29 Chapter 7: Machine Learning Using Java 30 Examples 30 tools list 30 Chapter 8: Natural Language Processing 33 Introduction 33 Examples 33 Text Matching or Similarity 33 Chapter 9: Neural Networks 34 Examples 34 Getting Started: A Simple ANN with Python 34 Backpropagation - The Heart of Neural Networks 37 1. Weights Initialisation 37 2. Forward Pass 38 3. Backward