Battle of the Clouds Technical Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paoli Battlefield Preservation Fund P.O

Paoli Battlefield Preservation Fund P.O. Box 173 • Malvern, PA 19355 • (484)-320-7173 An IRC 501(c)(3) Pennsylvania Non-Profit Corporation Dear Business Owner, We need your support to help sponsor TWO events for TWO community non-profits which are all-volunteer organizations dedicated to help us preserve our future? We are asking you to help The Paoli Battlefield Preservation Fund (PBPF), and the Paoli Memorial Association (PMA) as they continue to work in preserving, maintaining, and educating the public about this hallowed ground right in our own backyard. Last year, we started the process to become a National Historic Landmark, one of only around 2,500 sites around the entire United States. We are currently 60% of the way through the process and need your help to continue. We also need your help in maintaining our sites where the 2nd oldest Revolutionary War monument stands, where veterans’ remembrance events were held since 1817!! Please see the last page in this package to see all of our sponsorship levels. Starting on Tuesday, June 13th, we will be hosting Stars of 1777 at the Mather Planetarium at West Chester University. We have two shows at 6:30pm and 7:30pm where director, Dr. Karen Schwarz will show you what the sky looked like during the Battle of Paoli, fought on the night of September 20th, 1777. We also will also include many other interesting bits of information about the constellations in the summer sky. On Saturday, September 23rd from 11:00am to 4:00pm, we have the 5tth Annual Paoli Battlefield Heritage Day, which is a community event held at the Paoli Battlefield in Malvern. -

ESSSAR Masthead

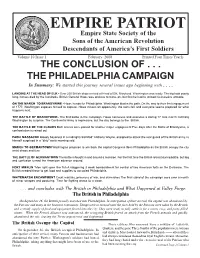

EMPIRE PATRIOT Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution Descendants of America’s First Soldiers Volume 10 Issue 1 February 2008 Printed Four Times Yearly THE CONCLUSION OF . THE PHILADELPHIA CAMPAIGN In Summary: We started this journey several issues ago beginning with . LANDING AT THE HEAD OF ELK - Over 260 British ships arrived at Head of Elk, Maryland. Washington was ready. The trip took overly long, horses died by the hundreds. British General Howe was anxious to move on, but first he had to unload his massive armada. ON THE MARCH TO BRANDYWINE - Howe heads for Philadelphia. Washington blocks the path. On the way to their first engagement of 1777, Washington exposes himself to capture, Howe misses an opportunity, the rains fall, and everyone seems prepared for what happens next. THE BATTLE OF BRANDYWINE- The first battle in the campaign. Howe conceives and executes a daring 17 mile march catching Washington by surprise. The Continental Army is impressive, but the day belongs to the British. THE BATTLE OF THE CLOUDS Both armies were poised for another major engagement Five days after the Battle of Brandywine, a confrontation is rained out PAOLI MASSACRE Bloody bayonets in a midnight raid Mad” Anthony Wayne, assigned to attack the rear guard of the British army, is himself surprised in a “dirty” early morning raid. MARCH TO GERMANTOWN Washington prepares to win back the capital Congress flees Philadelphia as the British occupy the city amid chaos and fear. THE BATTLE OF GERMANTOWN The battle is fought in and around a mansion. For the first time the British retreat during battle, but fog and confusion turned the American advance around. -

History and Causes of the Extirpation of the Providence Petrel (Pterodroma Solandri) on Norfolk Island

246 Notornis, 2002, Vol. 49: 246-258 0029-4470 O The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. 2002 History and causes of the extirpation of the Providence petrel (Pterodroma solandri) on Norfolk Island DAVID G. MEDWAY 25A Norman Street, New Plymouth, New Zealand [email protected] Abstract The population of Providence petrels (Pterodroma solandri) that nested on Norfolk Island at the time of 1st European settlement of that island in 1788 was probably > 1 million pairs. Available evidence indicates that Europeans harvested many more Providence petrels in the years immediately after settlement than previously believed. About 1,000,000 Providence petrels, adults and young, were harvested in the 4 breeding seasons from 1790 to 1793 alone. Despite these enormous losses, many Providence petrels were apparently still nesting on Norfolk Island in 1795 when they are last mentioned in documents from the island. However, any breeding population that may have survived there until 1814 when Norfolk Island was abandoned temporarily was probably exterminated by the combined activities of introduced cats and pigs which had become very numerous by the time the island was re-occupied in 1825. Medway, D.G. 2002. History and causes of the exhrpation of the Providence petrel (Pterodroma solandri) on Norfolk Island. Notornis 49(4): 246-258. Keywords Norfolk Island; Providence petrel; Pterodroma solandri; human harvesting; mammalian predation; extupation INTRODUCTION in to a hole which was concealed by the birds Norfolk Island (29" 02'S, 167" 57'E; 3455 ha), an making their burrows slant-wise". From the Australian external territory, is a sub-tropical summit, King had a view of the whole island and island in the south-west Pacific. -

ESSAY REVIEW Chronicling the Second Great Age of Discovery

ESSAY REVIEW Chronicling the Second Great Age of Discovery From Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains: Major Stephen Long's Expedition, 1819-1820. Edited by MAXINE BENSON. (Golden: Fulcrum, Inc., 1988. xxvii, 41 Op. Illustrations, color plates, maps, bibliography, index. $20.00.) Voyage to the Southern Ocean: The Letters oj Lieutenant William Reynolds jrom the U.S. Exploring Expedition, 1838-1842. Edited by ANNE HOFFMAN CLEAVER and E. JEFFREY STANN. (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1988. xxxix, 325p. Illustrations, maps, appendixes, bibliography, index. $24.95.) The Nagle Journal: A Diary oj the Life oj Jacob Nagle, Sailor, From the Year 1775 to 1841. Edited by JOHN C. DANN. (New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1988. xxx, 402p. Maps, illustrations, color plates, appen- dixes, glossary, index. $27.50.) These three books chronicle the adventures of men who ventured into the unknown in what is now becoming recognized as a unique second "Great Age of Discovery." Two of the accounts concern the stories of men sent out on U.S. Government exploring expeditions. A third, the journals of Jacob Nagle, chronicle the remarkable global peregrinations of an American sailor impressed into the British navy at the time of the American Revolution. His adventures in some ways call up memories of Sinbad, the Sailor, though his travels are demonstrably real. For a long time the important literature of exploration in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was compartmentalized into "land" and "sea" categories; scholars made few attempts either to link these exploration narratives to any single cultural process or to see them as more than mere adventure stories. -

Henry Clinton Papers, Volume Descriptions

Henry Clinton Papers William L. Clements Library Volume Descriptions The University of Michigan Finding Aid: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/clementsead/umich-wcl-M-42cli?view=text Major Themes and Events in the Volumes of the Chronological Series of the Henry Clinton papers Volume 1 1736-1763 • Death of George Clinton and distribution of estate • Henry Clinton's property in North America • Clinton's account of his actions in Seven Years War including his wounding at the Battle of Friedberg Volume 2 1764-1766 • Dispersal of George Clinton estate • Mary Dunckerley's account of bearing Thomas Dunckerley, illegitimate child of King George II • Clinton promoted to colonel of 12th Regiment of Foot • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot Volume 3 January 1-July 23, 1767 • Clinton's marriage to Harriet Carter • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton's property in North America Volume 4 August 14, 1767-[1767] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Relations between British and Cherokee Indians • Death of Anne (Carle) Clinton and distribution of her estate Volume 5 January 3, 1768-[1768] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton discusses military tactics • Finances of Mary (Clinton) Willes, sister of Henry Clinton Volume 6 January 3, 1768-[1769] • Birth of Augusta Clinton • Henry Clinton's finances and property in North America Volume 7 January 9, 1770-[1771] • Matters concerning the 12th Regiment of Foot • Inventory of Clinton's possessions • William Henry Clinton born • Inspection of ports Volume 8 January 9, 1772-May -

Continental Army: Valley Forge Encampment

REFERENCES HISTORICAL REGISTRY OF OFFICERS OF THE CONTINENTAL ARMY T.B. HEITMAN CONTINENTAL ARMY R. WRIGHT BIRTHPLACE OF AN ARMY J.B. TRUSSELL SINEWS OF INDEPENDENCE CHARLES LESSER THESIS OF OFFICER ATTRITION J. SCHNARENBERG ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION M. BOATNER PHILADELPHIA CAMPAIGN D. MARTIN AMERICAN REVOLUTION IN THE DELAWARE VALLEY E. GIFFORD VALLEY FORGE J.W. JACKSON PENNSYLVANIA LINE J.B. TRUSSELL GEORGE WASHINGTON WAR ROBERT LECKIE ENCYLOPEDIA OF CONTINENTAL F.A. BERG ARMY UNITS VALLEY FORGE PARK MICROFILM Continental Army at Valley Forge GEN GEORGE WASHINGTON Division: FIRST DIVISION MG CHARLES LEE SECOND DIVISION MG THOMAS MIFFLIN THIRD DIVISION MG MARQUES DE LAFAYETTE FOURTH DIVISION MG BARON DEKALB FIFTH DIVISION MG LORD STIRLING ARTILLERY BG HENRY KNOX CAVALRY BG CASIMIR PULASKI NJ BRIGADE BG WILLIAM MAXWELL Divisions were loosly organized during the encampment. Reorganization in May and JUNE set these Divisions as shown. KNOX'S ARTILLERY arrived Valley Forge JAN 1778 CAVALRY arrived Valley Forge DEC 1777 and left the same month. NJ BRIGADE departed Valley Forge in MAY and rejoined LEE'S FIRST DIVISION at MONMOUTH. Previous Division Commanders were; MG NATHANIEL GREENE, MG JOHN SULLIVAN, MG ALEXANDER MCDOUGEL MONTHLY STRENGTH REPORTS ALTERATIONS Month Fit For Duty Assigned Died Desert Disch Enlist DEC 12501 14892 88 129 25 74 JAN 7950 18197 0 0 0 0 FEB 6264 19264 209 147 925 240 MAR 5642 18268 399 181 261 193 APR 10826 19055 384 188 116 1279 MAY 13321 21802 374 227 170 1004 JUN 13751 22309 220 96 112 924 Totals: 70255 133787 1674 968 1609 3714 Ref: C.M. -

Chronology of the American Revolution

INTRODUCTION One of the missions of The Friends of Valley Forge Park is the promotion of our historical heritage so that the spirit of what took place over two hundred years ago continues to inspire both current and future generations of all people. It is with great pleasure and satisfaction that we are able to offer to the public this chronology of events of The American Revolution. While a simple listing of facts, it is the hope that it will instill in some the desire to dig a little deeper into the fascinating stories underlying the events presented. The following pages were compiled over a three year period with text taken from many sources, including the internet, reference books, tapes and many other available resources. A bibliography of source material is listed at the end of the book. This publication is the result of the dedication, time and effort of Mr. Frank Resavy, a long time volunteer at Valley Forge National Historical Park and a member of The Friends of Valley Forge Park. As with most efforts of this magnitude, a little help from friends is invaluable. Frank and The Friends are enormously grateful for the generous support that he received from the staff and volunteers at Valley Forge National Park as well as the education committee of The Friends of Valley Forge Park. Don R Naimoli Chairman The Friends of Valley Forge Park ************** The Friends of Valley Forge Park, through and with its members, seeks to: Preserve…the past Conserve…for the future Enjoy…today Please join with us and help share in the stewardship of Valley Forge National Park. -

Brandywine Battlefield Preservation Plan: Revolution in the Peaceful Valley (Map Atlas)

December, 2013 Brandywine MAP ATLAS Battlefield Preservation Plan Revolution in the Peaceful Valley CHESTER AND DELAWARE COUNTIES, PA Prepared by Chester County Planning Commission & John Milner Associates, Inc. Funded by The American Battlefi eld The 7th Preservation Program Pennsylvania Regiments (ABPP Grant Number Brandywine Flag GA-2255-11-003) The Brandywine Battlefield Preservation Plan: Revolution in the Peaceful Valley (Map Atlas) December 2013 Funded by the American Battlefield Preservation Program ABPP Grant Number GA-2255-11-003 Prepared by the Chester County Planning Commission & John Milner Associates, Inc. Chester County Board of Commissioners Delaware County Council Ryan Costello Tom McGarrigle Kathi Cozzone Mario J. Civera, Jr. Terence Farrell John P. McBlain Colleen P. Morrone Chester County Planning Commission David J. White Ronald T. Bailey, Executive Director David Ward, Assistant Director Delaware County Planning Department Carol Stauffer, Director, Planning Services Division John E. Pickett, Director of Planning* Christopher Bittle, Graphic Artist, Photographer Yinka Adesubokan, Associate Planner Yvonne Guthrie, Administrative Assistant Beverly Barnes, Historic Preservation Planner Elizabeth Kolb, Graphic Artists Jill Hall, Historic Preservation Planner Karen Marshall, Historic Preservation Officer Jake Michael, Project Manager Record copies of this document can be obtained Tyler Semder, GIS Specialist from: Jeannine Speirs, Senior Planner Kristen L. McMasters National Park Service John Milner and Associates American Battlefield Protection Program Wade Catts, Associate Director 1201 Eye Street NW (2287) Tom Scofield, Preservation Planner Washington, DC 20005 Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Disclaimer: Commission This material is based upon work assisted by a James M. Vaughan, Executive Director grant from the Department of the Interior, Barbara Franco, Executive Director* National Park Service. -

NJS: an Interdisciplinary Journal Winter 2017 107

NJS: An Interdisciplinary Journal Winter 2017 107 Hills, Huts, and Horse-Teams: The New Jersey Environment and Continental Army Winter Encampments, 1778-1780 By Steven Elliott DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14713/njs.v3i1.67 New Jersey’s role as a base for the Continental Army during the War of Independence has played an important part in the state’s understanding of its role in the American Revolution, and continues to shape the state’s image as the “Cockpit of the Revolution,” and “Crossroads of the American Revolution” today. This article uncovers how and why the Continental Army decided to place the bulk of its forces in northern New Jersey for two consecutive winters during the war. Unlike the more renowned Valley Forge winter quarters, neither New Jersey encampment has received significant scholarly attention, and most works that have covered the topic have presumed the state’s terrain offered obvious strategic advantages for an army on the defensive. This article offers a new interpretation, emphasizing the army’s logistical needs including forage for its animals and timber supplies for constructing winter shelters. The availability of these resources, rather than easily defended rough terrain or close-proximity to friendly civilians, led Washington and his staff to make northern New Jersey its mountain home for much of the war. By highlighting to role of the environment in shaping military strategy, this article adds to our understanding of New Jersey’s crucial role in the American struggle for independence. Introduction In early December, 1778, patriot soldiers from Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia arrived at the southern foothills of New Jersey’s Watchung Mountains and began erecting a log-hut winter encampment near Middlebrook. -

Manly, Warringah and Pittwater: First Fleet Records of Events, 1788-1790

Manly, Warringah and Pittwater: First Fleet Records of Events, 1788-1790 No. 5: Survey of Middle Harbour: 21st to 24th April, 1788. Acknowledgement The authors gratefully acknowledge assistance given by the staff of the Mitchell Library, Sydney. Copyright: Shelagh and George Champion, 1990. ISBN 0 9596484 7 X. The discovery of Middle Harbour above the Spit, and in particular the report by Captain Hunter of a run of fresh water feeding into the upper part of it, apparently led to Governor Phillip’s expedition of 15th April, 1788, which began in the Manly area and proceeded overland until the run of fresh water was reached. Our article, ‘Finding the right track’ deals with the exploration, 15th to 18th April. Another consequence of the discovery was a survey of Middle Harbour, carried out by Captain Hunter, Lieutenant Bradley, and James Keltie, the master of the Sirius. Seaman Jacob Nagle was a member of Governor Phillip’s boat crew. When this crew was not needed, Phillip used to send them out fishing at night. Nagle claimed that on one such excursion they found Middle Harbour, above the Spit: “On one of these excurcions, one night shooting the seen [seine] at the head of Middle Harbour, as we supposed, and shifting a long a rising sandy beach towards the north side, we found a narrow entrance, and going over the bank of sand, we discovered an other branch runing to the westward, full of coves, though we ware as far as this beach when surveying with the Govenor but did not discover the entrance of this branch. -

Collection 1454

Collection 1454 Cadwalader Family Papers 1623-1962, bulk 1776-1880 606 boxes, 233 vols., 242.4 lin. feet Contact: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107 Phone: (215) 732-6200 FAX: (215) 732-2680 http://www.hsp.org Original Processing by: Brett M. Reigh Original Processing Completed: July 1999 Additional Processing by: Joanne Danifo, Tory Kline, Jeff Knowles, Cary Majewicz, Rachel Moskowitz Additional Processing Completed: January 2007 Sponsor for Additional Processing: Phoebe W. Haas Charitable Trust Restrictions: None Related Collections at HSP: See page 18 © 2007 The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved. Cadwalader Family papers Collection 1454 Cadwalader Family Papers Collection 1454 Table of Contents Abstract 1 Background note 1 Scope & content 5 Overview of arrangement 8 Series descriptions 9 Separation report 18 Related materials 18 Bibliography 18 Languages represented 18 Subjects 19 Administrative information 21 Box and folder listings 22 Series 1: Miscellaneous deeds and correspondence 22 Series 2: General John Cadwalader papers 22 Series 3: General Thomas Cadwalader papers 31 Series 4: George Croghan papers 81 Series 5: Phineas Bond papers 84 Series 6: Judge John Cadwalader papers 96 Series 7: General George Cadwalader papers 132 Series 8: Charles E. Cadwalader papers 159 Series 9: J. Francis Fisher papers 167 Series 10: Peter McCall papers 171 Series 11: Later additions to the collection 179 Series 12: Maps 183 Appendix A: Cadwalader family tree 187 The Historical Society of Pennsylvania Cadwalader Family papers Collection 1454 Cadwalader Family Papers, 1623-1962 (bulk 1776-1880) 606 boxes, 233 vols., 242.4 lin. feet Collection 1454 Abstract The Cadwalader family papers document the Cadwalader family through four generations in America. -

Appendix a Detailed Historical Research in Support of the Battle of the Clouds Project

Appendix A Detailed Historical Research in Support of the Battle of the Clouds Project Detailed Historical Research in Support of the Battle of the Clouds Project Robert Selig, Thomas J. McGuire, and Wade Catts, 2013 American Battlefield Protection Program Grant GA-2255-12-005 Prepared for Chester County Planning. John Milner Associates, Inc., West Chester, PA Compiled August 17, 2013 This document contains a compilation of technical questions posed by the County of Chester as part of a project funded by the American Battlefield Protection Program in 2013 to research and document the Battle of the Clouds which took place September 16, 1777. Nineteen questions were developed in order to produce a technical report containing details of the battle such as order of battle, areas of engagement, avenues of approach and retreat, and encampment areas. Research was conducted by John Milner Associates of West Chester under the guidance of Wade Catts and his research team consisting of Dr. Robert Selig and Thomas J. McGuire. Due to the obscurity of the battle and the lack of detailed first-hand accounts, some of the questions could not be answered conclusively and are so noted. Following is a summary of the questions: Intro Q1 - Were the troop strengths in this battle the same as Brandywine? After Brandywine Q2 - Did George Washington make his headquarters at the Stenton House in Germantown during the Continental encampment on September 13? Q3 - Were any troops left to cover Levering’s Ford or Matson’s Ford after Washington crossed back to the west