Broadband and the Wisconsin Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadband ADSL2+ Modem Dm111pspv2 User Manual

Broadband ADSL2+ Modem DM111PSPv2 User Manual 350 East Plumeria Drive San Jose, CA 95134 USA August 2011 202-10913-01 v1.0 Broadband ADSL2+ Modem DM111PSPv2 © 2011 NETGEAR, Inc. All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any language in any form or by any means without the written permission of NETGEAR, Inc. Technical Support Thank you for choosing NETGEAR. To register your product, get the latest product updates, get support online, or for more information about the topics covered in this manual, visit the Support website at http://support.netgear.com. Phone (US & Canada only): 1-888-NETGEAR Phone (Other Countries): Check the list of phone numbers at http://support.netgear.com/app/answers/detail/a_id/984. Trademarks NETGEAR, the NETGEAR logo, and Connect with Innovation are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of NETGEAR, Inc. and/or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. Information is subject to change without notice. Other brand and product names are registered trademarks or trademarks of their respective holders. © 2011 NETGEAR, Inc. All rights reserved. Statement of Conditions To improve internal design, operational function, and/or reliability, NETGEAR reserves the right to make changes to the products described in this document without notice. NETGEAR does not assume any liability that may occur due to the use, or application of, the product(s) or circuit layout(s) described herein. 2 Contents Chapter 1 Hardware Setup Unpack Your New Modem. 7 Hardware Features . 8 Label . 8 Back Panel. 8 Front Panel . -

7022417378.Pdf

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Implementing Public Safety Broadband ) PS Docket No. 12-94 Provisions of the Middle Class Tax Relief and ) Job Creation Act of 2012 ) ) Implementing a Nationwide, Broadband, ) PS Docket No. 06-229 Interoperable Public Safety Network in the 700 ) MHz Band ) ) Service Rules for the 698-746, 747-762 and ) WT Docket No. 06-150 777-792 MHz Bands ) COMMENTS OF THE COALITION OF WISPS FOR FIRSTNET The Coalition of WISPs 1 for FirstNet (“WISP Coalition”), a group of wireless Internet service providers, by counsel and pursuant to Sections 1.415 and 1.419 of the rules of the Federal Communications Commission (“Commission”), hereby submits these comments in response to the Commission’s Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (“ NPRM ”) 2 that seeks comment on certain proposals to implement the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012 (“Public Safety Spectrum Act") 3 and the nationwide public safety broadband network in the 700 MHz band. The WISP Coalition includes small businesses who deliver broadband Internet access services and, in some cases, competitive local exchange services to their communities. The 1 “WISPs” are Wireless Internet Service Providers. The WISPs joining this filing are A Better Wireless, NISP, LLC; Aircado, Inc.; AirLink Internet Services, LLC; Aristotle, Inc.; aXess America, LLC; CellTex Networks, LLC; Digital Video Services; First Step Internet, LLC; Helix Technologies, Inc.; JAB Wireless, Inc.; M 2 Connections, a division of JKM Consulting, Inc.; New Wave Net Corp.; Rural Broadband Network Services, LLC; STL WiMax; Washington Broadband, Inc.; and Wireless ETC, Inc. -

Digital Subscriber Lines and Cable Modems Digital Subscriber Lines and Cable Modems

Digital Subscriber Lines and Cable Modems Digital Subscriber Lines and Cable Modems Paul Sabatino, [email protected] This paper details the impact of new advances in residential broadband networking, including ADSL, HDSL, VDSL, RADSL, cable modems. History as well as future trends of these technologies are also addressed. OtherReports on Recent Advances in Networking Back to Raj Jain's Home Page Table of Contents ● 1. Introduction ● 2. DSL Technologies ❍ 2.1 ADSL ■ 2.1.1 Competing Standards ■ 2.1.2 Trends ❍ 2.2 HDSL ❍ 2.3 SDSL ❍ 2.4 VDSL ❍ 2.5 RADSL ❍ 2.6 DSL Comparison Chart ● 3. Cable Modems ❍ 3.1 IEEE 802.14 ❍ 3.2 Model of Operation ● 4. Future Trends ❍ 4.1 Current Trials ● 5. Summary ● 6. Glossary ● 7. References http://www.cis.ohio-state.edu/~jain/cis788-97/rbb/index.htm (1 of 14) [2/7/2000 10:59:54 AM] Digital Subscriber Lines and Cable Modems 1. Introduction The widespread use of the Internet and especially the World Wide Web have opened up a need for high bandwidth network services that can be brought directly to subscriber's homes. These services would provide the needed bandwidth to surf the web at lightning fast speeds and allow new technologies such as video conferencing and video on demand. Currently, Digital Subscriber Line (DSL) and Cable modem technologies look to be the most cost effective and practical methods of delivering broadband network services to the masses. <-- Back to Table of Contents 2. DSL Technologies Digital Subscriber Line A Digital Subscriber Line makes use of the current copper infrastructure to supply broadband services. -

Etherfast® Cable Modem Take Off at the Speed of Broadband Internet

Instant Broadband Series EtherFast ™ ® Cable Take Off at the Speed of Modem Broadband Internet with USB and Ethernet Connection Own Simple and Affordable Cable Internet Connectivity re you ready to step up to high-speed broadband Internet? The EtherFast A Linksys provides you with® Cablethe perfect Modem solution with USBfor a from fast and easy Internet connection. Now you can make the most of the Internet and cruise the Web at speeds you never imagined possible. Cable Modem Internet service means no more waiting for lagging downloads—even the most graphic-intensive Web pages load in seconds. And if you’re looking for convenience and affordability, the EtherFast ® Cable Modem with USB really delivers! Installation is quick and easy. The Plug-and-Play EtherFast with USB connects directly to any USB-ready PC—just plug it in and you’re ready to surf the Internet. Or connect® Cable it toModem your LAN using a Linksys router and share that speed with everyone on your network. So if you’re ready to enjoy broadband Internet speed, then EtherFast ® Cable Modem with USB you’re ready for the EtherFast Model No.: BEFCMU10 BenefitsBenefits Linksys. It’s the easiest and most® Cableaffordable Modem way with to harness USB from the full potential of the Internet. • Easy Installation - One Phone Call Completes FeaturesFeatures Setup • Built-In 10/100 Ethernet Port • Much Faster Download and Upload Than Dial- Up Internet Connections • With USB Connection, No Ethernet Card is Required • Keeps the Telephone Line Free for Calls While • Up to 42.88 Mbps -

Migration to 3G Wireless Broadband Internet and Real Options: the Case of an Operator in India

ARTICLE IN PRESS Telecommunications Policy 30 (2006) 400–419 www.elsevierbusinessandmanagement.com/locate/telpol Migration to 3G wireless broadband internet and real options: The case of an operator in India Venkata Praveen TanguturiÃ, Fotios C. Harmantzis Telecommunications Management, School of Technology Management, Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA Abstract The paper focuses on third generation wireless technologies and on alternative technologies for wireless local area networks. The authors present the evolutionary migration path from second to third generation systems. Technological, economic and behavioral factors related to decision-making towards the migration are proposed. As an example, the paper studies the case of the national incumbent operator of India. It analyzes qualitatively the migration problem from the perspective of the operator, the equipment manufacturer and the users. For the quantitative analysis, real options are used to value the investment decisions. The analysis suggests that the initial (sunk) investment cost, the average revenue per user, the growth of the subscriber base and the volatility of the markets are the key factors in the investment process. r 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: 3G; GSM; CDMA; Wireless; Broadband; India; UMTS; India; Wi-Fi; Real options 1. Introduction The evolution of the internet has led to the convergence of telecommunications networks and computers. Benefits associated with the World Wide Web (WWW) are of great importance nowadays: people are able to communicate via e-mail, perform data transfers, online shopping, online auctions, etc. Traditionally, internet services have been provided by internet service providers (ISPs) using modems, with data rates limited to 56.6 kbp. -

HP Mobile Broadband Modules

QuickSpecs HP Mobile Broadband Modules Overview Introduction Wireless Wide Area Network (WWAN) is an optional feature sold separately or as an add-on feature on select HP notebooks, Ultrabooks and tablets HP Mobile Broadband modules provide integrated WWAN technology such as LTE**, DC-HSPA+, HSPA+, HSDPA, HSUPA, WCDMA, GSM, GPRS, EDGE, CDMA, and GNSS connectivity over several radio frequency bands. (Select modules also supports 2G / 3G roaming). HP Mobile Broadband modules use this integrated WWAN technology to connect to wireless networks operated by mobile network operators in many countries worldwide. (Separately purchased mobile operator service required.) ** 4G LTE not available on all products or in all countries. A WWAN connection requires wireless data service contract, network operator support, and is not available in all areas. Contact a service provider (e.g. Mobile Network Operator) to determine the coverage area and availability. Connection speeds will vary due to location, environment, network conditions, and other factors. Selected HP Mobile Broadband Wireless notebooks support Wireless WAN (WWAN) as an after-market option if ordered as a Wireless WAN (WWAN) ready configuration option. This provides customers the opportunity of adding Wireless WAN (WWAN) as an after-market option providing cost-efficient solution of adding WWAN post purchase. By offering customers this WWAN ready configuration option; HP can offer customers and integrated wireless wide area network (WWAN) option by way of after-market option kit. If the -

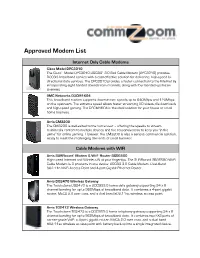

Approved Modem List

Approved Modem List Internet Only Cable Modems Cisco Model DPC3010 The Cisco® Model DPC3010 DOCSIS® 3.0 8x4 Cable Modem (DPC3010) provides DOCSIS broadband service with a cost-effective solution for delivering high-speed bi- directional data services. The DPC3010 provides a faster connection to the Internet by incorporating eight bonded downstream channels along with four bonded upstream channels SMC Networks D3CM1604 This broadband modem supports downstream speeds up to 640Mbps and 120Mbps on the upstream. The extreme speed allows faster streaming HD videos, file downloads and high-speed gaming. The D3CM1604 is the ideal solution for your house or small home business. Arris CM3200 The CM3200 is well-suited to the home user – offering the speeds to stream multimedia content to multiple devices and the responsiveness to keep you “in the game” for online gaming. However, the CM3200 is also a serious commercial solution, ready to meet the challenging demands of small business. Cable Modems with WIFI Arris SURFboard® Modem & Wi-F® Router SBG6580 High-speed Internet and Wireless N at your fingertips. The SURFboard SBG6580 Wi-Fi Cable Modem is 3 products in one device: DOCSIS 3.0 Cable Modem, Dual-Band 802.11n Wi-Fi Access Point and 4-port Gigabit Ethernet Router. Arris DG2470 Wireless Gateway The Touchstone DG2470 is a DOCSIS3.0 home data gateway supporting 24 x 8 channel bonding for up to 960Mbps of broadband data. It combines a 4-port gigabit router, MoCA 2.0 over coax, and a dual band 802.11ac wireless access point. Arris TG2472 Wireless Gateway The Touchstone TG2472 is a DOCSIS3.0 home telephony gateway supporting 24 x 8 channel bonding for up to 960Mbps of broadband data. -

Analysis of Wifi and Wimax and Wireless Network Coexistence

International Journal of Computer Networks & Communications (IJCNC) Vol.6, No.6, November 2014 ANALYSIS OF WIFI AND WIMAX AND WIRELESS NETWORK COEXISTENCE Shuang Song and Biju Issac School of Computing, Teesside University, Middlesbrough, UK ABSTRACT Wireless networks are very popular nowadays. Wireless Local Area Network (WLAN) that uses the IEEE 802.11 standard and WiMAX (Worldwide Interoperability for Microwave Access) that uses the IEEE 802.16 standard are networks that we want to explore. WiMAX has been developed over 10 years, but it is still unknown to most people. However compared to WLAN, it has many advantages in transmission speed and coverage area. This paper will introduce these two technologies and make comparisons between WiMAX and WiFi. In addition, wireless network coexistence of WLAN and WiMAX will be explored through simulation. Lastly we want to discuss the future of WiMAX in relation to WiFi. KEY WORDS WiMAX, WiFi, wireless network, wireless coexistence, network simulation 1. INTRODUCTION With the development of multimedia communication, people need wireless broadband access with higher speed, larger coverage and mobility. The emergence of WiMAX (Worldwide Interoperability for Microwave Access) technology met the people's demand for wireless Internet to some extent. If wireless LAN technology (WLAN) solves the access problem of the "last one hundred meters", then WiMAX technology is the best access solution of the "last mile". Though WiMAX is an emerging and extremely competitive wireless broadband access technology, the development prospects of its market is still unknown. Hybrid networks as a supplement to cell based or IP packet based services, can fully reflect the characteristics of wide network coverage. -

An Overview of Mobile Broadband in 4G Long Term Evolution and Emerging Strategies for Resolving Deployment Limitations in Developing Countries

International Journal of Applied Engineering Research ISSN 0973-4562 Volume 12, Number 17 (2017) pp. 6447-6451 © Research India Publications. http://www.ripublication.com An Overview of Mobile Broadband in 4G Long Term Evolution and Emerging Strategies for Resolving Deployment Limitations in Developing Countries Agboje O.E1, Oni O.O2 and Nkordeh N.S3 Department of Electrical and Information Engineering, College of Engineering, Covenant University Ota. Ogun state, Nigeria. 2Orcid: 0000-0002-4467-5953 Abstract as wired or wireless access since different type of network have their unique capability, strength, flaws and inherent costs The role of mobile broadband in the society cannot be involved. overemphasized in the global internet ecosystem. Its deployment and penetration is basically to satisfy end users It encompasses the use of several devices, networks and increasing demand for data services and improve their quality applications. The intensive usage of data services in mobile of life. Therefore the need for a fast and reliable mobile broadband has significantly reduced the volume of voice broadband connection is an important driver of business and services traffic [2].The need for a faster and a more reliable economic advancement of any nation. The increasing demand and affordable broadband connectivity is becoming certain of data for new applications and request for more services by with growth in global economy and the universal human end users in global mobile competitive market motivated the desire to improve on their quality of life with affordable Third Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) to introduce access to health services, banking and education which are Long Term Evolution (LTE). -

Wireless (Select Models Only) User Guide © Copyright 2009 Hewlett-Packard Product Notice Development Company, L.P

Wireless (Select Models Only) User Guide © Copyright 2009 Hewlett-Packard Product notice Development Company, L.P. This user guide describes features that are Windows is a U.S. registered trademark of common to most models. Some features Microsoft Corporation. Bluetooth is a may not be available on your computer. trademark owned by its proprietor and used by Hewlett-Packard Company under license. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The only warranties for HP products and services are set forth in the express warranty statements accompanying such products and services. Nothing herein should be construed as constituting an additional warranty. HP shall not be liable for technical or editorial errors or omissions contained herein. First Edition: August 2009 Document Part Number: 539901-001 Table of contents 1 Using wireless devices (select models only) Identifying wireless and network status icons ...................................................................................... 2 Using the wireless controls ................................................................................................................... 3 Using the wireless button ..................................................................................................................... 4 Using Wireless Assistant software (select models only) ...................................................................... 5 Using HP Connection Manager (select models only) .......................................................................... -

Broadband Cable Modem with USB & Ethernet

BRG-3520 Broadband Cable Modem with USB & Ethernet Key Features Overview • DOCSIS 1.0-compliant cable modem, DOCSIS 1.1 hardware- Hitron’s BRG-3520 is a full-featured yet economical, entry-level ready, easily software upgradeable DOCSIS 1.0-compliant cable modem with both Ethernet and USB interfaces. Its neat, compact design and small footprint • Full-featured compact, economical cable modem with USB make it ideal for home, office or campus use. and Ethernet ports The BRG-3520 is the perfect solution for cable operators who • RJ-45 10/100BaseT Ethernet port serves as interface for a want to add the value of broadband Internet connectivity to their computer or local area network current or future customer base. High-speed data transfers up to 38 Mbps downstream and 10 Mbps upstream are possible over • USB port allows easy plug-and-play attachment of the latest the installed HFC cable plant. Hitron’s software lets operators Windows-based PCs assign up to 15 IP addresses for deployment in small office or dormitory settings. • Capable of handling downstream data transmission speeds up to 38Mbps, upstream to 10Mbps Installation is so quick and easy it can be done even by end- users. The USB port allows plug-and-play connectivity without • Extensive SNMP management support, MIB-II, Ethernet-like opening the computer or performing complex configurations. MIB, Bridge MIB, Cable Device MIB, Baseline privacy Front panel LEDs clearly display both cable and network status. Interface MIB, RF Interface MIB A browser-based utility allows convenient viewing of network sta- tistics. DHCP and TFTP clients allow the modem to automatically • OS-independent, works with all major software platforms get its IP address and configuration data from network servers, without the intervention of either the user or installer. -

Broadband Access Across Oklahoma During Covid-19

COVID-19 RESPONSE BROADBAND ACCESS ACROSS OKLAHOMA DURING COVID-19 Learn about the importance of broadband connectivity in our society during the pandemic. 94 The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance 100 of broadband connectivity in our society. K-12 and col- 90 79 lege students have transitioned to online learning, many 80 74 professionals have shifted to teleworking arrangements, 70 and applying for unemployment or small business assis- 60 48 tance programs typically requires fling documents via the 50 internet. Individuals and households lacking an internet 40 connection are even more cut of from friends and family 30 during social distancing. A survey of Oklahoma school 20 districts in the early stages of the pandemic found that 10 167,000 out of 700,000 students (24%) lacked an internet 0 connection at home. Being disconnected – regardless of All Rural the reason – has never been a bigger disadvantage. U.S. Oklahoma Even before COVID-19 arrived, the Oklahoma broad- band situation was relatively poor. A 2018 report ranked Figure 1: Broadband availability rates for U.S. and Okla- Oklahoma 47th out of 50 states in terms of average homa (2017). speeds and percent of residents connected. The most Source: FCC 2018 Broadband Deployment Report recent ofcial data from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) shows that nationally, 94% of people have access to the ofcial “broadband” threshold speed of 25 Megabits per second (Mbps) download and 3 Mbps upload. In Oklahoma, that number stands at 79%. More strikingly, only 48% of our rural residents have access to a broadband connection, which is signifcantly lower than CONTACT the 74% at the national level (Figure 1).