The Planning and Implementation of the Don Valley Brick Works' Restoration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breathing New Life Into

Breathing New Life into 2003 Don Watershed Report Card A Message to Those Who Cherish the Don If you brought this report card home to your parents, you would be sent to bed without dinner. Far too many Cs and Ds, not a single A, and — heaven forbid — an F, glaring from the page. But restoration is hardly a series of simple questions and answers that can easily be slotted into good or bad, right or wrong. It's much more than that. It takes a longer view. The grades are nowhere near good enough, true, but some very important groundwork has been laid in the past 10 years to ensure major strides from here on. First off, let's address that F. We know we can do better in caring for water, and now, we have a means to improve that grade through the recently completed Wet Weather Flow Management Master Plan for the City of Toronto. Once it's put in place, water quality will improve substantially, not only in the Don River, but everything it feeds. The plan will take at least 25 years to implement; we still must include the munici- palities outside of Toronto into a broader watershed plan. Bold commitments by federal, provincial, and municipal governments must be made to ensure we have the resources required to really make this happen. There are quantifiable victories as well. Thanks to changes to five weirs, salmon and other fish now migrate more freely up the Don for the first time in a century. We have seen the completion of the first phase of the Don Valley Brick Works, and a number of other regeneration projects: Little German Mills Creek, The Bartley Smith Greenway, Milne Hollow, and the establishment of the Charles Sauriol Nature Reserve. -

A Time for Bold Steps

A TIME FOR BOLD STEPS: THE DON WATERSHED REPORT CARD 2OOO Prepared By The Don Watershed Regeneration Council Front cover: Drawing of proposed mouth of the Don River, prepared for The Task Force to Bring Back the Don, by Hough Woodland Naylor Dance Leinster, February 2000. Facing page: Gray treefrog. D2repcar.qxd 11/3/2002 7:53 PM Page I A TIME FOR BOLD STEPS THE DON WATERSHED REPORT CARD 2000 Prepared By The Don Watershed Regeneration Council Renewing and protecting the natural environment in our living city and region. D2repcar.qxd 11/3/2002 7:53 PM Page II ISBN 0-9684992-4-4 II D2repcar.qxd 11/3/2002 7:53 PM Page III CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . .IV CARING FOR WATER . .1 Indicator 1: Flow Pattern . .4 Indicator 2: Water Quality - Human Use . .6 Indicator 3: Water Quality - Aquatic Habitats . .8 Indicator 4: Stormwater Management . .12 CARING FOR NATURE . .14 Indicator 5: Woodlands . .16 Indicator 6: Wetlands . .18 Indicator 7: Meadows . .20 Indicator 8: Riparian Habitat . .22 Indicator 9: Frogs . .24 Indicator 10: Fish . .26 CARING FOR COMMUNITY . .28 Indicator 11: Public Understanding and Support . .30 Indicator 12: Classroom Education . .32 Indicator 13: Responsible Use and Enjoyment . .34 PROTECT WHAT IS HEALTHY . .36 Indicator 14: Protected Natural Areas . .38 REGENERATE WHAT IS DEGRADED . .40 Indicator 15: Regeneration Projects . .42 TAKE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE DON . .44 Indicator 16: Personal Stewardship . .46 Indicator 17: Business and Institutional Stewardship . .48 Indicator 18: Municipal Stewardship . .50 GLOSSARY . .52 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . .56 TABLES Table 1 - A Water Quality Index . .6 Maps Invertebrate Sampling Stations . .8 Frog Monitoring Stations . -

Toronto's Natural Environment Trail Strategy

Natural Environment Trail Strategy June 2013 City of Toronto Prepared by LEES+AssociatesLandscape Architects and Planners with ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The City of Toronto’s Natural Environment Trail Strategy is a product of over fifteen years of cumulative trail management experiences, outreach, stewardship and efforts by many groups and individuals. We would like to thank the following people who helped create, shape and inform the strategy in 2012: Natural Environment Trails Program Working Group Garth Armour Jennifer Kowalski Rob Mungham Michael Bender Scott Laver Brittany Reid Edward Fearon Roger Macklin Alex Shevchuk Norman DeFraeye Beth Mcewen Karen Sun Ruthanne Henry Brian Mercer Ed Waltos Natural Environment Trails Program Advisory Team Lorene Bodiam Jennifer Hyland Jane Scarffe Christina Bouchard Dennis Kovacsi William Snodgrass Susanne Burkhardt Sibel Sarper Jane Weninger Susan Hughes City of Toronto Teresa Bosco Jennifer Gibb Wendy Strickland Jack Brown Jim Hart Richard Ubbens Chris Clarke Janette Harvey Mike Voelker Chris Coltas Amy Lang Soraya Walker Jason Doyle Nancy Lowes Cara Webster Carlos Duran Cheryl Post Sean Wheldrake Jason Foss Kim Statham Alice Wong Councillor Mary Fragedakis Christine Speelman Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Adele Freeman Alexis Wood Adam Szaflarski Amy Thurston Keri McMahon Vince D’Elia Arlen Leeming Steven Joudrey Susan Robertson Natural Environment Trail Strategy Project Team Lees+Associates Azimuth Decarto Sustainable Trails The Planning Environmental Consulting, Ltd. Ltd. Partnership consulting, -

MUD CREEK LOST RIVERS LOOP (Moore Ave., Milkmans Walane, Mount Pleasant, St

MUD CREEK LOST RIVERS LOOP (Moore Ave., Milkmans WaLane, Mount Pleasant, St. l Clair k loop) Experience a walk along routes of three buried waterways, all hidden from public view decades ago in the interest of progress. Enjoy the natural serenity of living ponds on the former site of Toronto’s largest brick works, right in the heart of the city. Public Transit: Getting there; Saturday only 28A TTC Bus from Davisville Subway station. Free daily Evergreen shuttle bus from Broadview Subway For over 100 years, this the metal plate are some of the Lost station. 1 unique property was home to Rivers of the Don Watershed; The Getting home; Take the 28A TTC Bus back to Davisville Subway Station or return to the Don Valley Brick Works. The site large Exploring the Lower Don map Broadview Subway station via the Evergreen shuttle bus. was perfect for brick making, with a shows where you are in relation to the *Public transit routes and schedules are subject to change. Please check with provider. TTC Information: www.ttc.ca or 416-393-4636. Visit www.ebw.evergreen.ca for their shuttle bus schedule. quarry of clay and shale, access to lake. water from Mud Creek, and nearby Walk through the open- Parking: Paid parking available at Evergreen Brick Works. railroads for transportation. In 1989, 2 when brick production ended, the city, air building on your left, called The Pavilions, and out to the Terrace. Food and Washrooms: Available at Evergreen Brick Works. province, conservation authority and private donors purchased the property Until the early-1980s, this large area was an active quarry with a 40 meter Level of Difficulty/Accessibility: The trail varies from gravel, dirt to hard- to protect and restore the lands. -

Toronto Toronto, ON

What’s Out There® Toronto Toronto, ON Welcome to What’s Out There Toronto, organized than 16,000 hectares. In the 1970s with urban renewal, the by The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) waterfront began to transition from an industrial landscape with invaluable support and guidance provided by to one with parks, retail, and housing—a transformation that numerous local partners. is ongoing. Today, alluding to its more than 1,400 parks and extensive system of ravines, Toronto is appropriately dubbed This guidebook provides fascinating details about the history the “City within a Park.” The diversity of public landscapes and design of just a sampling of Toronto’s unique ensemble of ranges from Picturesque and Victorian Gardenesque to Beaux vernacular and designed landscapes, historic sites, ravines, Arts, Modernist, and even Postmodernist. and waterfront spaces. The essays and photographs within these pages emerged from TCLF’s 2014 partnership with This guidebook is a complement to TCLF’s much more Professor Nina-Marie Lister at Ryerson University, whose comprehensive What’s Out There Toronto Guide, an interactive eighteen urban planning students spent a semester compiling online platform that includes all of the enclosed essays plus a list of Toronto’s significant landscapes and developing many others—as well overarching narratives, maps, and research about a diversity of sites, designers, and local themes. historic photographs— that elucidate the history of design The printing of this guidebook coincided with What’s Out There of the city’s extensive network of parks, open spaces, and Weekend Toronto, which took place in May 2015 and provided designed public landscapes. -

LOWER DON(Pottery Road to Cherry Street)

LOWER DON (Pottery Road to Cherry Street) WaImagine a Lower Don River, l in k the late 1800s, teeming with salmon and meandering through wide marshes and tree-lined banks. Imagine the 1900s, with its engineered, channelized watercourse and its banks lined with polluting industries. This degradation of the valley was compounded by the addition of the Don Valley Parkway. Today, the Lower Don is the site of one of the largest urban environmental restoration projects in the world. This walk begins in the richly the Lower Don Trail that runs north/ 1 Public Transit: Getting there; From Broadview Station, all northbound historic site of Todmorden Mills, south. Make another left and proceed buses bring you to Pottery Road (announced as Mortimer). Walk 10 minutes former location of a 19th century paper south along the trail. The Don River down Pottery Road to Todmorden Mills. mill, brewery and gristmill. This gristmill should be on your righthand side. Getting home; Either walk north on Cherry Street to Mill Street or walk was the second gristmill in Upper The trail continues down the south on Cherry Street to Lakeshore Boulevard to take the 72B Pape bus to Canada, the first being on the Humber 2 River. Construction of the Don Valley Don, it passes through a stand Union Station. of wild plum trees. Raspberry canes *Public transit routes and schedules are subject to change. Please check with provider. Parkway (DVP) has isolated a former TTC Information: www.ttc.ca or 416-393-4636. oxbow of the Don River on this site. grow along the trail, possibly obscured Visit the 9.2-hectare Todmorden Mills by large and very invasive stands of Parking: From Pottery Road, enter Todmorden Mills Heritage Museum Wildflower Preserve that has examples Japanese Knotweed. -

Alterations to a Heritage Property – 550 Bayview Avenue

REPORT FOR ACTION Alterations to a Heritage Property – 550 Bayview Avenue Date: January 12, 2017 To: City Council From: Chief Planner and Executive Director, City Planning Division Wards: Ward 29 – Toronto Danforth SUMMARY This report recommends that City Council approve the conservation strategy generally described for the heritage property located at 550 Bayview Avenue ("The Don Valley Brick Works"). The current tenant is seeking to alter Building 16, one of the historic industrial buildings on the property, in order to enhance accessibility, extend its seasonal use, and to expand its programming. The property is owned by the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority and managed by the City of Toronto. It is currently under lease to Evergreen. RECOMMENDATIONS The Chief Planner and Executive Director, City Planning Division recommends that: 1. City Council approve the alterations to the heritage property at 550 Bayview Avenue (The Don Valley Brick Works), in accordance with Section 33 of the Ontario Heritage Act, to allow for alterations to Building 16, on the lands known municipally in the 2017 as 550 Bayview Avenue, with such alterations substantially in accordance with plans and drawings prepared by LGA Architectural Partners, dated December 16, 2016, and on file with the Senior Manager, Heritage Preservation Services; and the Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA), prepared by ERA Architects Inc. dated January 6, 2017 and date-stamped received by the City Planning Division on January 6, 2017, and on file with the Senior Manager, Heritage Preservation Services, all subject to and in accordance with a Conservation Plan satisfactory to the Senior Manager, Heritage Preservation Services and subject the following additional conditions: Alterations to a Heritage Property – 550 Bayview Av Page 1 of 33 a. -

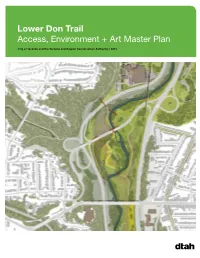

Lower Don Trail Access, Environment + Art Master Plan

Lower Don Trail Access, Environment + Art Master Plan City of Toronto and the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority / 2013 Lower Don Trail Access, Environment + Art Master Plan Prepared for: City of Toronto Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Prepared by: DTAH Project Lead, Landscape Architecture and Urban Design AECOM Ecology, Transportation, Civil Engineering Public Space Workshop Trail Connectivity LURA Consultation Andrew Davies Design Public Art SPH Planning + Consulting Accessibility September 2013 With special thanks to the staff of TRCA and the City of Toronto Parks, Transportation, Culture and Planning Departments. Thanks also to Metrolinx, Evergreen, and those members of the public who attended the open house session or contacted us with their comments on the future of the Lower Don Trail. “As the years go on and the population increases, there will be a need of these and more lands, and in life where so much appears futile, this one thing will remain. In essence, those who continue to support the work of conservation can say, I have lived here, I have done something positive to ensure that its natural beauty and natural values continue.” – Charles Sauriol (1904-1995), local resident and lifelong advocate for conservation in the Don Valley. Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 1 / Introduction 1.1 Background 3 1.2 Problem Statement, Goals and Context 6 1.3 Recommended Design Principles 7 2 / Process 2.1 Project Timeline 9 2.2 Existing Conditions 10 2.3 Previous Studies 12 2.4 SWOT Analysis 13 2.5 Public Consultation -

Nature-Based Experiences – Report on Current Conditions

Don River Watershed Plan Nature-based Experiences – Report on Current Conditions 2009 Prepared by: Toronto and Region Conservation Don River Watershed Plan: Nature-based Experiences – Report on Current Conditions Table of Contents Table of Contents............................................................................................................................ 2 List of Tables................................................................................................................................... 2 List of Figures.................................................................................................................................. 2 1.0 Introduction............................................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Nature-based experiences in an urban landscape.................................................................. 4 2.1 Health and wellbeing ............................................................................................................ 4 2.2 Nature-based experience and greenspace preferences ..................................................... 5 2.3 Environmental education and stewardship .......................................................................... 7 2.4 Income and opportunities..................................................................................................... 7 2.5 User conflicts and encroachment........................................................................................ -

Tracing the Social and Environmental History of the Don River

Tracing the Social and Environmental History of the Don River D.C. Grose, Taylor Brothers Paper Mill, c.1860. Toronto Public Library, TRL, Historical Picture Collection, B 3-27c. 1 “the destroying cancer of the port” “The whole of the marsh to the East, once deep and clear water, is the work of the Don, and in the Bay of York, where now its destructive mouths are turned, vegetation shews [sic] itself in almost every direction, prognosticating the approaching conversion of this beautiful sheet of water into another marshy delta of the Don." -Capt. Hugh Richardson, c.1834. I’d like to begin with a couple of quotations which I think capture the degree of irritation which many 19th century Torontonians felt for the Don River. Here Captain Hugh Richardson has, as historian Henry Scadding noted in 1873, “some hard things [to say] of the river Don.” In his words, the Don was "the destroying cancer of the Port." His rage was directed towards the Don’s “destructive industry” in carrying great quantities of silt into the harbour and interfering with navigation. 2 Silt from the Don River entering the harbour through the eastern gap, September 1962. Toronto Port Authority Archives, PC 14/6845 This image—taken over 100 years later—illustrates the amount of silt carried into the harbour by the Don. 3 The Don’s “true value and capabilities” would not be revealed until “the right men appeared, possessed of the intelligence, the vigour and the wealth equal to the task of bettering nature by art on a considerable scale…. -

Lower Don Trail Master Plan Refresh: September 17, 2019 Public Meeting

LOWER DON TRAIL MASTER PLAN 2019 REFRESH Welcome to this Public Meeting for the Lower Don Trail Master Plan 2019 Refresh. This is the primary opportunity for the public to engage the team led by the City of Toronto in partnership with Evergreen as the overall project moves forward. This evening we will introduce the project, present the draft recommendations of the Master Plan Refresh, and discuss next steps. Feedback We welcome your feedback on our work to date. Please ask for an Agenda / Comments Sheet from the registration table to record your thoughts. You can leave it at the registration table tonight or send your feedback by e-mail (contact below) by Friday September 27, 2019. Contact Brendan McKee, Project Manager Parks, Forestry and Recreation | Horticulture City of Toronto Scarborough Civic Centre, 150 Borough Drive Toronto, Ontario M1P 4N6 t: 416-396-4192 e: [email protected] Website www.toronto.ca/lowerdon LOWER DON TRAIL MASTER PLAN 2019 REFRESH CITY OF TORONTO + EVERGREEN IN PARTNERSHIP DTAH 09.17.2019 Project Purpose & Outcome This Refresh represents the second Reasons for the Refresh include: round of master planning the Lower Don Trail. It follows and updates the A different way of thinking: Since 2013, both of the profile of the Don Valley lands 2013 Master Plan, which resulted in a and the public conversation regarding their future have grown and become more number of successful improvements sophisticated. There is now a general consensus that the Don Valley should be thought to the trail and its surroundings. of, and planned for, as a single cohesive park space, rather than a collection of pieces. -

Download TFN Newsletter – Dec 2019

Since 1923 Number 648 December 2019 Blanding’s turtles. Photo Lynn Pady. ( See page 15) REGULARS FEATURES About TFN 14 Butternut Tree Planting at Jim Baillie 6 Coming Events 13 Nature Reserve Extracts from Outings Reports 12 Toronto Vines: Curare and Grape 15 7 In the News Families Junior Naturalists 11 Junior Naturalists Events 10 Tree of the Month: Cucumber-tree 8 Keeping In Touch 15 Volunteer Profile: Kristina Jackson 9 Lecture Notice 16 Lecture Report 5 Action Committee Report 14 President’s Report 2 Book Sale Notice 15 TFN Outings 3 Weather (This Time Last Year) 13 TFN 648-2 Toronto Field Naturalist December 2019 PRESIDENT’S REPORT Over the last few years, a steady stream of municipal By all accounts, however, private land is no magic bullet. strategy documents, coupled with a boom in grassroots Provisioning the so-called green infrastructure stewardship, citizen science and other environmental requirements that our urbanity demands will require initiatives, have heralded a growing effort to protect and investments of new public lands. enhance what remains of Toronto's wilds. The keyword Those of you who were able to attend our monthly lecture here, however, is "remains." Toronto's rise has come at the on September 8 benefitted from ecologist Chris Cormack's expense of some 90% of its historic woodlands and an intimate exploration of one of the more promising even greater relative volume of wetlands, savannas, and initiatives to expand Toronto's wilds: The Meadoway. The shrubland. At present, it is estimated that a scant 4% of this successful restoration process that summoned the city can still be classified as ecologically significant.