Watling & Auster.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Di Camillo Et Al 2017

This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyedit version of an article published in Biodiversity and Conservation on 23 December 2017 (First Online). The final authenticated version is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-017-1492-8 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10531-017-1492-8 An embargo period of 12 months applies to this Journal. This paper has received funding from the European Union (EU)’s H2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 643712 to the project Green Bubbles RISE for sustainable diving (Green Bubbles). This paper reflects only the authors’ view. The Research Executive Agency is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. © 2017. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 AUTHORS' ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Building a baseline for habitat-forming corals by a multi-source approach, including Web Ecological Knowledge - Cristina G Di Camillo, Department of Life and Environmental Sciences, Marche Polytechnic University, CoNISMa, Ancona, Italy, [email protected] - Massimo Ponti, Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences and Interdepartmental Research Centre for Environmental SciencesUniversity of Bologna, CoNISMa, Ravenna, Italy - Giorgio Bavestrello, Department of Earth, Environment and Life Sciences, University of Genoa, CoNISMa, Genoa, Italy - Maja Krzelj, Department of Marine Studies, University of Split, Split, Croatia - Carlo Cerrano, Department of Life and Environmental Sciences, Marche Polytechnic University, CoNISMa, Ancona, Italy Received: 12 January 2017 Revised: 10 December 2017 Accepted: 14 December 2017 First online: 23 December 2017 Cite as: Di Camillo, C.G., Ponti, M., Bavestrello, G. -

Symbiosis Regulation in a Facultatively Symbiotic Temperate Coral: Zooxanthellae Division and Expulsion

Coral Reefs (2008) 27:601–604 DOI 10.1007/s00338-008-0363-x NOTE Symbiosis regulation in a facultatively symbiotic temperate coral: zooxanthellae division and expulsion J. Dimond Æ E. Carrington Received: 18 October 2007 / Accepted: 10 February 2008 / Published online: 29 February 2008 Springer-Verlag 2008 Abstract Zooxanthellae mitotic index (MI) and expul- Keywords Temperate coral Astrangia Zooxanthellae sion rates were measured in the facultatively symbiotic Expulsion Facultative symbiosis scleractinian Astrangia poculata during winter and summer off the southern New England coast, USA. While MI was significantly higher in summer than in winter, mean Introduction expulsion rates were comparable between seasons. Corals therefore appear to allow increases in symbiont density Many anthozoans and some other invertebrates are well when symbiosis is advantageous during the warm season, known for their endosymbiotic associations with zooxan- followed by a net reduction during the cold season when thellae (Symbiodinium sp. dinoflagellates). Living within zooxanthellae may draw resources from the coral. Given gastrodermal cells, zooxanthellae utilize host wastes and previous reports that photosynthesis in A. poculata sym- translocate photosynthetic products to the animal, in some bionts does not occur below approximately 6 C, cases fulfilling nearly all of the host’s energy demands considerable zooxanthellae division at 3 C and in darkness (Muscatine 1990). Host cells have a flexible, but finite suggests that zooxanthellae are heterotrophic at low sea- capacity for zooxanthellae, and must therefore either grow sonal temperatures. Finally, examination of expulsion as a additional cells to accommodate dividing symbionts or function of zooxanthellae density revealed that corals with regulate their numbers (Muscatine et al. -

Checklist of Fish and Invertebrates Listed in the CITES Appendices

JOINTS NATURE \=^ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Checklist of fish and mvertebrates Usted in the CITES appendices JNCC REPORT (SSN0963-«OStl JOINT NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Report distribution Report Number: No. 238 Contract Number/JNCC project number: F7 1-12-332 Date received: 9 June 1995 Report tide: Checklist of fish and invertebrates listed in the CITES appendices Contract tide: Revised Checklists of CITES species database Contractor: World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL Comments: A further fish and invertebrate edition in the Checklist series begun by NCC in 1979, revised and brought up to date with current CITES listings Restrictions: Distribution: JNCC report collection 2 copies Nature Conservancy Council for England, HQ, Library 1 copy Scottish Natural Heritage, HQ, Library 1 copy Countryside Council for Wales, HQ, Library 1 copy A T Smail, Copyright Libraries Agent, 100 Euston Road, London, NWl 2HQ 5 copies British Library, Legal Deposit Office, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ 1 copy Chadwick-Healey Ltd, Cambridge Place, Cambridge, CB2 INR 1 copy BIOSIS UK, Garforth House, 54 Michlegate, York, YOl ILF 1 copy CITES Management and Scientific Authorities of EC Member States total 30 copies CITES Authorities, UK Dependencies total 13 copies CITES Secretariat 5 copies CITES Animals Committee chairman 1 copy European Commission DG Xl/D/2 1 copy World Conservation Monitoring Centre 20 copies TRAFFIC International 5 copies Animal Quarantine Station, Heathrow 1 copy Department of the Environment (GWD) 5 copies Foreign & Commonwealth Office (ESED) 1 copy HM Customs & Excise 3 copies M Bradley Taylor (ACPO) 1 copy ^\(\\ Joint Nature Conservation Committee Report No. -

Estimate of Microbial Biodiversity in Electra Pilosa and Alcyonium Digitatum

UPTEC X06 045 Examensarbete 20 p December 2006 Estimate of microbial biodiversity in Electra pilosa and Alcyonium digitatum Hélène Harnemark Molecular Biotechnology Programme Uppsala University School of Engineering UPTEC X 06 045 Date of issue 2006-11 Author Hélène Harnemark Title (English) Estimate of microbial biodiversity in Electra pilosa and Alcyonium digitatum Abstract In attempting to characterize the microbial population of the marine species Electra pilosa and Alcyonium digitatum this study yielded a wide range of microbial growth using in vivo cultivation techniques on agar plates and PCR. The methods of the study were evaluated to the benefit of coming studies. Keywords Electra pilosa, Alcyonium digitatum, PCR, agar cultivation, marine organisms Supervisors Erik Hedner Department of medicinal chemistry, division of pharmacognosy, Uppsala University Scientific reviewer Anders Backlund Department of medicinal chemistry, division of pharmacognosy, Uppsala University Project name Sponsors Language Security English Classification ISSN 1401-2138 Supplementary bibliographical information Pages 22 Biology Education Centre Biomedical Center Husargatan 3 Uppsala Box 592 S-75124 Uppsala Tel +46 (0)18 4710000 Fax +46 (0)18 555217 Estimate of microbial biodiversity in Electra pilosa and Alcyonium digitatum Hélène Harnemark Sammanfattning Våra världshav är en relativt ny källa för vetenskapliga upptäckter. Det har länge varit svårt att utnyttja och undersöka något på havets bottnar. När resurser och utrustning under de senaste årtiondena blivit bättre har vi sett att här finns mycket att finna. Man har exempelvis hittat havslevande djur som kan skydda sig från parasiter utan att ha ett immunförsvar. De har tagit hjälp av bakterier som tillverkar olika giftiga ämnen som sprids i djurets omgivningar eller stannar på dess yta, vilket ger ett skydd från vissa rovdjur. -

Marlin Marine Information Network Information on the Species and Habitats Around the Coasts and Sea of the British Isles

MarLIN Marine Information Network Information on the species and habitats around the coasts and sea of the British Isles Pink sea fan (Eunicella verrucosa) MarLIN – Marine Life Information Network Marine Evidence–based Sensitivity Assessment (MarESA) Review John Readman & Dr Keith Hiscock 2017-03-30 A report from: The Marine Life Information Network, Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. Please note. This MarESA report is a dated version of the online review. Please refer to the website for the most up-to-date version [https://www.marlin.ac.uk/species/detail/1121]. All terms and the MarESA methodology are outlined on the website (https://www.marlin.ac.uk) This review can be cited as: Readman, J.A.J. & Hiscock, K. 2017. Eunicella verrucosa Pink sea fan. In Tyler-Walters H. and Hiscock K. (eds) Marine Life Information Network: Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Reviews, [on-line]. Plymouth: Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.17031/marlinsp.1121.1 The information (TEXT ONLY) provided by the Marine Life Information Network (MarLIN) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. Note that images and other media featured on this page are each governed by their own terms and conditions and they may or may not be available for reuse. Permissions beyond the scope of this license are available here. Based on a work at www.marlin.ac.uk (page left blank) Date: 2017-03-30 Pink sea fan (Eunicella verrucosa) - Marine Life Information Network See online review for distribution map Two fans of Eunicella verrucosa showing the two morphs, pink and white. -

Guide to the Identification of Precious and Semi-Precious Corals in Commercial Trade

'l'llA FFIC YvALE ,.._,..---...- guide to the identification of precious and semi-precious corals in commercial trade Ernest W.T. Cooper, Susan J. Torntore, Angela S.M. Leung, Tanya Shadbolt and Carolyn Dawe September 2011 © 2011 World Wildlife Fund and TRAFFIC. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-9693730-3-2 Reproduction and distribution for resale by any means photographic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems of any parts of this book, illustrations or texts is prohibited without prior written consent from World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Reproduction for CITES enforcement or educational and other non-commercial purposes by CITES Authorities and the CITES Secretariat is authorized without prior written permission, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Any reproduction, in full or in part, of this publication must credit WWF and TRAFFIC North America. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC network, WWF, or the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The designation of geographical entities in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WWF, TRAFFIC, or IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership are held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint program of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Cooper, E.W.T., Torntore, S.J., Leung, A.S.M, Shadbolt, T. and Dawe, C. -

Alcyonium Digitatum

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Alcyonium digitatum (Dead Man's Fingers) Priority 3 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Anthozoa (Corals, Sea Pens, Sea Fans, Sea Anemones) Order: Alcyonacea (Soft Corals) Family: Alcyoniidae (Soft Corals) General comments: none No Species Conservation Range Maps Available for Dead Man's Fingers SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: NA State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: NA Regional Endemic: NA High Regional Conservation Priority: NA High Climate Change Vulnerability: Alcyonium digitatum is highly vulnerable to climate change. Understudied rare taxa: Recently documented or poorly surveyed rare species for which risk of extirpation is potentially high (e.g. few known occurrences) but insufficient data exist to conclusively assess distribution and status. *criteria only qualifies for Priority 3 level SGCN* Notes: Historical: NA Culturally Significant: NA Habitats Assigned to Dead Man's Fingers: Formation Name Subtidal Macrogroup Name Subtidal Bedrock Bottom Habitat System Name: Erect Epifauna Macrogroup Name Subtidal Coarse Gravel Bottom Habitat System Name: Erect Epifauna Macrogroup Name Subtidal Mud Bottom Habitat System Name: Unvegetated Macrogroup Name Subtidal Sand Bottom Habitat System Name: Unvegetated Stressors Assigned to Dead Man's Fingers: No Stressors Currently Assigned to Dead Man's Fingers or other Priority 3 SGCN. Species Level Conservation Actions Assigned to Dead -

Deep‐Sea Coral Taxa in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico: Depth and Geographical Distribution

Deep‐Sea Coral Taxa in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico: Depth and Geographical Distribution by Peter J. Etnoyer1 and Stephen D. Cairns2 1. NOAA Center for Coastal Monitoring and Assessment, National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, Charleston, SC 2. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC This annex to the U.S. Gulf of Mexico chapter in “The State of Deep‐Sea Coral Ecosystems of the United States” provides a list of deep‐sea coral taxa in the Phylum Cnidaria, Classes Anthozoa and Hydrozoa, known to occur in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 1). Deep‐sea corals are defined as azooxanthellate, heterotrophic coral species occurring in waters 50 m deep or more. Details are provided on the vertical and geographic extent of each species (Table 1). This list is adapted from species lists presented in ʺBiodiversity of the Gulf of Mexicoʺ (Felder & Camp 2009), which inventoried species found throughout the entire Gulf of Mexico including areas outside U.S. waters. Taxonomic names are generally those currently accepted in the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), and are arranged by order, and alphabetically within order by suborder (if applicable), family, genus, and species. Data sources (references) listed are those principally used to establish geographic and depth distribution. Only those species found within the U.S. Gulf of Mexico Exclusive Economic Zone are presented here. Information from recent studies that have expanded the known range of species into the U.S. Gulf of Mexico have been included. The total number of species of deep‐sea corals documented for the U.S. -

Marlin Marine Information Network Information on the Species and Habitats Around the Coasts and Sea of the British Isles

MarLIN Marine Information Network Information on the species and habitats around the coasts and sea of the British Isles Tubularia indivisa and cushion sponges on tide- swept turbid circalittoral bedrock MarLIN – Marine Life Information Network Marine Evidence–based Sensitivity Assessment (MarESA) Review Thomas Stamp and Dr Harvey Tyler-Walters 1970-01-01 A report from: The Marine Life Information Network, Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. Please note. This MarESA report is a dated version of the online review. Please refer to the website for the most up-to-date version [https://www.marlin.ac.uk/habitats/detail/1164]. All terms and the MarESA methodology are outlined on the website (https://www.marlin.ac.uk) This review can be cited as: Stamp, T.E. & Tyler-Walters, H. -unspecified-. [Tubularia indivisa] and cushion sponges on tide-swept turbid circalittoral bedrock. In Tyler-Walters H. and Hiscock K. (eds) Marine Life Information Network: Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Reviews, [on-line]. Plymouth: Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.17031/marlinhab.1164.1 The information (TEXT ONLY) provided by the Marine Life Information Network (MarLIN) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. Note that images and other media featured on this page are each governed by their own terms and conditions and they may or may not be available for reuse. Permissions beyond the scope of this license are available here. Based -

A Possible Method for Improving the Conservation Status of a Ellisella

Research Article Mediterranean Marine Science Indexed in WoS (Web of Science, ISI Thomson) and SCOPUS The journal is available on line at http://www.medit-mar-sc.net http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/mms.2076 Pruning treatment: A possible method for improving the conservation status of a Ellisella paraplexauroides Stiasny, 1936 (Anthozoa, Alcyonacea) population in the Chafarinas Islands? LUIS SÁNCHEZ -TOCINO1, ANTONIO DE LA LINDE RUBIO2, M SOL LIZANA ROSAS1, TEODORO PÉREZ GUERRA1 and JOSE MANUEL TIERNO DE FIGUEROA1 1 Departamento de Zoología. Facultad de Ciencias. Universidad de Granada. Campus Fuentenueva s/n, 18071, Granada, Spain 2 Urbanización los Delfines, Pl 4, 2º, 11207, Algeciras, Cádiz, Spain Corresponding author: [email protected] Handling Editor: Emma Cebrian Received: 7 December 2017; Accepted: 11 July 2017; Published on line: 11 December 2017 Abstract In the present paper, the results of a four-year conservation study on the giant gorgonian Ellisella paraplexauroides in the Chafarinas Islands are reported. This species, currently protected in Spain, is present as isolated colonies or as a low number of them, except in the Chafarinas Islands, where higher densities can be found below a depth of 20 m. Nevertheless, as revealed by a previous study, a great number of colonies are partially covered by epibionts or totally dead. As a first objective of the present work, seven transects were performed in 2013 and 2014 to evaluate the percentage of colonies affected in areas that had not been previously sampled. Approximately between 35% and 95% of the colonies had different degrees of epibiosis or were dead. In 2015, ten transects were performed to specifically locate young colonies smaller than 15 cm, which could be indicative of popula- tion regeneration by sexual reproduction. -

Vulnerable Forests of the Pink Sea Fan Eunicella Verrucosa in the Mediterranean Sea

diversity Article Vulnerable Forests of the Pink Sea Fan Eunicella verrucosa in the Mediterranean Sea Giovanni Chimienti 1,2 1 Dipartimento di Biologia, Università degli Studi di Bari, Via Orabona 4, 70125 Bari, Italy; [email protected]; Tel.: +39-080-544-3344 2 CoNISMa, Piazzale Flaminio 9, 00197 Roma, Italy Received: 14 April 2020; Accepted: 28 April 2020; Published: 30 April 2020 Abstract: The pink sea fan Eunicella verrucosa (Cnidaria, Anthozoa, Alcyonacea) can form coral forests at mesophotic depths in the Mediterranean Sea. Despite the recognized importance of these habitats, they have been scantly studied and their distribution is mostly unknown. This study reports the new finding of E. verrucosa forests in the Mediterranean Sea, and the updated distribution of this species that has been considered rare in the basin. In particular, one site off Sanremo (Ligurian Sea) was characterized by a monospecific population of E. verrucosa with 2.3 0.2 colonies m 2. By combining ± − new records, literature, and citizen science data, the species is believed to be widespread in the basin with few or isolated colonies, and 19 E. verrucosa forests were identified. The overall associated community showed how these coral forests are essential for species of conservation interest, as well as for species of high commercial value. For this reason, proper protection and management strategies are necessary. Keywords: Anthozoa; Alcyonacea; gorgonian; coral habitat; coral forest; VME; biodiversity; mesophotic; citizen science; distribution 1. Introduction Arborescent corals such as antipatharians and alcyonaceans can form mono- or multispecific animal forests that represent vulnerable marine ecosystems of great ecological importance [1–4]. -

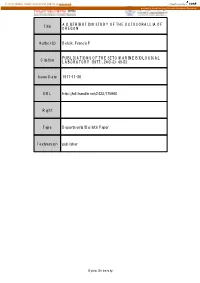

Title a DISTRIBUTION STUDY of the OCTOCORALLIA OF

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository A DISTRIBUTION STUDY OF THE OCTOCORALLIA OF Title OREGON Author(s) Belcik, Francis P. PUBLICATIONS OF THE SETO MARINE BIOLOGICAL Citation LABORATORY (1977), 24(1-3): 49-52 Issue Date 1977-11-30 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/175960 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University A DISTRIBUTION STUDY OF THE OCTOCORALLIA OF OREGON FRANCIS P. BELCIK Department of Biology, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina 27834, U.S.A. With Text-figure 1 and Tables 1-2 Introduction: The purpose of this report was to identify the species of octocorals, note their occurrence or distribution and also their numbers. The Octocorals of this report were collected :rhainly from the Oregonian Region. The majority of specimens were collected by the Oceanography Department of Oregon State University at depths below 86 meters. A few inshore species were collected at various sites along the Oregon Coast (see Fig. 1). Only two species were found in the Intertidal Zone; the bulk of the Octocoral fauna occur offshore in deeper water. Most of the deep water specimens are now deposited in the Oceanography Department of Oregon State University in Corvallis, Oregon. The inshore speci mens have remained in my personal collection. Identification Methods: No references have been published for the soft corals of Oregon; although col lections have possibly been made in the past. Helpful sources for identification, after the standard methods of corrosion, and spicule measurements have been made are: Bayer, 1961; Hickson, 1915; Kiikenthal, 1907, and 1913; Nutting, 1909 and 1912; Utinomi, 1960, 1961, and 1966 and Verrill, 1922.