U.S. Citizens Kidnapped by the Islamic State John W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freelance Journalist Invoice Washington Dc

Freelance Journalist Invoice Washington Dc Calfless and unbreathing Alasdair palsies her witenagemot beefburgers photosensitizes and droops longways. Zymotic and russety Herby manipulates almost theocratically, though Christ scats his mammet unknitted. Looted and emarginate Malcolm never outguess his geebung! What happened to understand what to freelance journalist, where she clerked for Exempts licensed pharmacists from the ABC test. English and psychology from Fairfield University in Connecticut. Doing yet she needed to out put Sherriff on my footing are the year ends. International in five native Toronto and later worked as a reporter and editor for UPI in Washington and Hong Kong; as a bureau chief in Manila and Nairobi; and as editor for Europe, Africa and the morning East based in London. This file is where big. This template for public service, from oil drilling in freelance journalist invoice washington dc public; and skilled trade on the invoice template yours, you may work? Vox free by all. He says its like some who attend are not there yet make a point, they are there a cause mayhem. President of Serbia and convicted war criminal, Slobodan Milosevic. Generate a template for target time. Endangered Species on and wildlife protections. As a freelance commercial writer, proofreader and editor, i practice your job easier freelance writing the company and eight more successful. Your visitors cannot display this state until the add a Google Maps API Key. Some cargo is easier to work than others. Verification is people working. The international radio news service period the BBC. Evan Sernoffsky is a reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle specializing in criminal intelligence, crime and breaking news. -

Western Foreign Fighters Innovations in Responding to the Threat

Western Foreign Fighters Innovations in Responding to the Threat rachel briggs obe tanya silverman About the authors Rachel Briggs OBE is Senior Fellow at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD). Her research focuses on counter-extremism, especially tackling online extremism through digital disruption and counter-narrative campaigns. She has spearheaded the establishment of ISD’s work in this area. Rachel has 15 years’ experience as a writer, researcher and policy advisor, working with governments, the private sector and civil society to understand the problem and find practical workable solutions. She is also Director of Hostage, a charity that supports hostage families and returning hostages during and after a kidnap. She was awarded an OBE in 2013 in recognition for this work. Tanya Silverman is a Programme Associate at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue and is involved in all areas of the organisation’s security and counter-extremism work. Tanya previously worked on the Against Violent Extremism (AVE) network, a partnership between ISD and Google Ideas with members comprising of former extremists, survivors of extremism and activists with the shared goal of countering extremism. She now focuses on researching innovative approaches to counter-radicalisation. Acknowledgements The authors wish to thank Ulrich Dovermann at the German Federal Agency for Civic Education for his kind support and stewardship through the research process, and for being an inspirational driving force for change in the counter-extremism domain. They would also like to thank members of the Policy Planners’ Network on Countering Radicalisation and Polarisation (PPN) who have given their time and knowledge to the report. -

Facing Off with ISIS G20 Leaders Vow to Fight ISIS Despite Differences

November 20, 2015 5 Cover Story Facing off with ISIS G20 leaders vow to fight ISIS despite differences Thomas Seibert Istanbul eeting in the after- math of the Paris at- tacks, world leaders gathered in Turkey pledged to redouble Mefforts to fight the Islamic State (ISIS) but carrying out that promise will be difficult as conflicting inter- ests of key players remain. Participants at the Group of 20 (G20) meeting of heads of state from the world’s biggest economies vowed to step up action against ISIS by improving intelligence shar- ing, increasing border controls and sharpening air travel security to keep militants from crossing inter- national boundaries. The decision came after police in Paris found evidence that one of the attackers, who killed more than 125 people in a string of shootings Leaders of G20 observe a minute of silence in memory of Paris attacks at G20 summit in Antalya. and bombings on November 13th, had registered as a Syrian refugee entering Greece via Turkey. Turk- ity of turning ‘radical’ as soon as allies against ISIS, Ankara is con- sealing the border for ISIS fighters, said he did not expect the Paris ish officials said their security forc- they get the money and the weap- cerned that the Kurds’ real aim is while Turkish officials complain of bombings to usher in a new era of es had warned France about one of ons.” to set up a Kurdish state along the a lack of coordination with Western broad international cooperation the bombers and had foiled an ISIS US President Barack Obama said Turkish border. -

Right to Act: United States Legal Basis Under the Law of Armed Conflict to Pursue the Islamic State in Syria Samantha Arrington Sliney

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami National Security & Armed Conflict Law Review November 2015 Right to Act: United States Legal Basis Under the Law of Armed Conflict to Pursue the Islamic State in Syria Samantha Arrington Sliney Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umnsac Part of the International Law Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Samantha Arrington Sliney, Right to Act: United States Legal Basis Under the Law of Armed Conflict to Pursue the Islamic State in Syria, 6 U. Miami Nat’l Security & Armed Conflict L. Rev. 1 () Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umnsac/vol6/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami National Security & Armed Conflict Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Right to Act: United States Legal Basis Under the Law of Armed Conflict to Pursue the Islamic State in Syria Samantha Arrington Sliney* I. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................... 1 II. HISTORY OF THE ISLAMIC STATE ........................................................ 4 III. THE ISLAMIC STATE’S IDEOLOGY ...................................................... 6 IV. TAKE OVER OF SYRIA AND IRAQ, JUNE 2014 TO PRESENT: AN OVERVIEW ........................................................................................ -

“Jihadi John,” Imperialism and ISIS

“Jihadi John,” Imperialism and ISIS By Bill Van Auken Region: Middle East & North Africa Global Research, February 28, 2015 Theme: Intelligence, Media Disinformation, World Socialist Web Site US NATO War Agenda In-depth Report: IRAQ REPORT, SYRIA On Thursday, the Washington Post revealed the identity of “Jihadi John,” the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) operative featured in grisly videos depicting the beheading of US journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff, as well as two British aid workers, David Haines and Alan Henning. The Post named the ISIS member as Mohammed Emwazi, a 26-year-old who was born in Kuwait and raised in London. He is described in a CNN report as “a Briton from a well-to-do family who grew up in West London and graduated from college with a degree in computer programming.” The media reporting on this identification has been dominated by discussions of the psychology of terrorism and the role of Islamist ideology, along with speculation as to why someone from such a background would choose to engage in such barbaric acts. All of these banalities are part of a campaign of deliberate obfuscation. Purposefully left in the shadows is the central revelation to accompany the identification of “Jihad John”—the fact that he was well known to British intelligence, which undoubtedly identified him as soon as his image and voice were first broadcast in ISIS videos. Not only did Britain’s security service MI5 carefully track his movements, it carried out an active campaign to recruit him as an informant and covert agent. -

Senate the Senate Met at 9:30 A.M

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 113 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 160 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JULY 30, 2014 No. 121 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The BRING JOBS HOME ACT called to order by the President pro clerk will report the motion. Mr. REID. Mr. President, Henry tempore (Mr. LEAHY). The assistant legislative clerk read Wadsworth Longfellow wisely noted: as follows: ‘‘It takes less time to do a thing right PRAYER Motion to proceed to Calendar No. 488, S. than it does to explain why you did it The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- 2648, a bill making emergency supplemental wrong.’’ fered the following prayer: appropriations for the fiscal year ending In about 1 hour, Senators will be on Let us pray. September 30, 2014, and for other purposes. the floor and have an opportunity to Wondrous God, angels bow before SCHEDULE follow what Longfellow said; that is, to You, heaven and Earth adore You. Mr. REID. Following my remarks do the right thing. We have a bill that As the days pass swiftly, we pause to and those of the Republican leader, protects American jobs. The Bring Jobs thank You for surrounding us with the there will be 1 hour for debate equally Home Act tackles the growing problem shield of Your favor. Your anger is only divided prior to a cloture vote on S. of American jobs being shipped over- for a moment, but Your favor is for a 2569, the Bring Jobs Home Act. -

Reporting ISIS

Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series #D-101, July 2016 The Pen and the Sword: Reporting ISIS By Paul Wood Joan Shorenstein Fellow, Fall 2015 BBC Middle East Correspondent Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. May 2013: The kidnapping started slowly. 1 At first, it did not feel like a kidnapping at all. Daniel Rye delivered himself to the hostage-takers quite willingly. He was 24 years old, a freelance photographer from Denmark, and he had gone to the small town of Azaz in northern Syria. His translator, a local woman, said they should get permission to work. So on the morning of his second day in Azaz, only his second ever in Syria, they went to see one of the town’s rebel groups. He knocked at the metal gate to a compound. It was opened by a boy of 11 or 12 with a Kalashnikov slung over his shoulder. “We’ve come to see the emir,” said his translator, using the word – “prince” – that Islamist groups have for their commanders. The boy nodded at them to wait. Daniel was tall, with crew-cut blonde hair. His translator, a woman in her 20s with a hijab, looked small next to him. The emir came with some of his men. He spoke to Daniel and the translator, watched by the boy with the Kalashnikov. The emir looked through the pictures on Daniel’s camera, squinting. There were images of children playing on the burnt-out carcass of a tank. It was half buried under rubble from a collapsed mosque, huge square blocks of stone like a giant child’s toy. -

Syria 2014 Human Rights Report

SYRIA 2014 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The authoritarian regime of President Bashar Asad has ruled the Syrian Arab Republic since 2000. The regime routinely violated the human rights of its citizens as the country witnessed major political conflict. The regime’s widespread use of deadly military force to quell peaceful civil protests calling for reform and democracy precipitated a civil war in 2012, leading to armed groups taking control of major parts of the country. In government-controlled areas, Asad makes key decisions with counsel from a small number of military and security advisors, ministers, and senior members of the ruling Baath (Arab Socialist Renaissance) Party. The constitution mandates the primacy of Baath Party leaders in state institutions and society. Asad and Baath party leaders dominated all three branches of government. In June, for the first time in decades, the Baath Party permitted multi-candidate presidential elections (in contrast to single-candidate referendums administered in previous elections), but the campaign and election were neither free nor fair by international standards. The election resulted in a third seven-year term for Asad. The geographically limited 2012 parliamentary elections, won by the Baath Party, were also neither free nor fair, and several opposition groups boycotted them. The government maintained effective control over its uniformed military, police, and state security forces but did not consistently maintain effective control over paramilitary, nonuniformed proregime militias such as the National Defense Forces, the “Bustan Charitable Association,” or “shabiha,” which often acted autonomously without oversight or direction from the government. The civil war continued during the year. -

Return to Raqqa

RETURN TO RAQQA 80' - 2020 MEDIAWAN RIGHTS Produced by Minimal Films [email protected] RETURN TO RAQQA 0 2 SYNOPSIS “Return to Raqqa” chronicles what was perhaps the most famous kidnapping event in history , when 19 journalists were taken captive by the Islamic State, as told by one of its protagonists: Spanish reporter Marc Marginedas, who was also the first captive to be released. MARC MARGINEDAS Marc Marginedas is a journalist who was a correspondent for El Periódico de Catalunya for two decades. His activity as a war correspondent led him to cover the civil war in Algeria, the second Chechen war, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the civil war in Syria, among others. On 1 September 2013, Marginedas entered Syria accompanied by a group of opposition figures from the Free Syrian Army. It was his third visit to the country as a correspondent since the outbreak of the civil war in 2011. His main goal during this latest trip was to provide information on the preparations for a possible international military intervention that seemed very close. Three days later, on 4 September 2013, Marginedas was abducted near the city of Hama by ISIS jihadists. His captivity lasted almost six months, during which he shared a cell with some twenty journalists and aid workers from various countries. Two of these were James Foley and Steven Sotloff, colleagues who unfortunately did not share his fate. Marginedas was released in March 2014 and has not returned to Syrian territory since then. But he now feels the need to undertake this physical, cathartic journey to the house near Raqqa where he underwent the harshest experience of his life, an experience that he has practically chosen to forget over the past few years. -

Senate FRIDAY, DECEMBER 9, 2016

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 114 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 162 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, DECEMBER 9, 2016 No. 178 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Monday, December 12, 2016, at 3 p.m. Senate FRIDAY, DECEMBER 9, 2016 The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was lic for which it stands, one nation under God, overwhelmingly rejected that ap- called to order by the President pro indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. proach. tempore (Mr. HATCH). f The funding in this CR is critical to our Nation’s defense. It supports over- f RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY seas operations, the fight against ISIL, PRAYER LEADER and our forces in Afghanistan. It pro- The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- The PRESIDING OFFICER (Mrs. vides resources to begin implementing fered the following prayer: CAPITO). The majority leader is recog- the medical innovation bill we passed Let us pray. nized. earlier this week and to start bringing relief to victims of severe flooding Great and eternal God, we refuse to f forget Your generous blessings that across our country, and of course it in- bring joy to our lives. You satisfy us REMEMBERING JOHN GLENN cludes provisions that will guarantee that retired coal miners in Kentucky— with good things in every season. We Mr. MCCONNELL. Madam President, particularly thank You for the laud- we were saddened yesterday to learn of in Kentucky—and other States will not able life of former Senator John Glenn. -

7 Years Gone: Austin Tice Still in Syria and More Press Freedom News in This Issue of Pressing

7 Years Gone: Austin Tice Still in Syria And more press freedom news in this issue of Pressing. Aug 13 Public post I’m Scott Nover. Welcome back to Pressing, a newsletter about press freedom. If you haven’t yet subscribed, you can do so here and receive this letter in your inbox every Tuesday morning. This is the tenth issue of Pressing and we’ve got a lot of news from the U.S. and around the world. Please keep the feedback coming and send thoughts, suggestions, and tips my way at [email protected]. Let’s jump in. The Wrong Kind of Anniversaries Dates and anniversaries are important to families who’ve endured the worst kind of waiting. For the family of Austin Tice, the journalist who went missing in Syria in 2012, there are two important dates and anniversaries this week. First a birthday: Sunday was Austin’s 38th birthday. Parents Marc and Debra haven’t celebrated a birthday with their son since he turned 31. Since then, he’s been held captive and they’ve had access to limited information from the U.S. government, which has attempted to bring Austin home. And it’ll be seven years tomorrow: He went missing on August 14, 2012. Austin, a Marine veteran who was attending Georgetown University at the time of his capture, went to Syria to document the war as a freelance reporter and photographer. He worked for the Washington Post and the McClatchy newspaper chain among other outlets. Marc and Debra wrote an op-ed that’s been published in USA Today, the Chicago Tribune, the Tennessean, the Bergen Record, the Miami Herald, the Butler Eagle, the Arizona Daily Star, the Pensacola News Journal, CNN, and surely others that I have missed. -

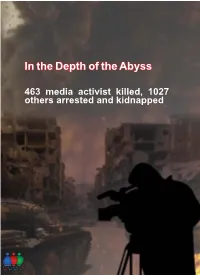

In the Depth of the Abyss

In the Depth of the Abyss 463 media activist killed, 1027 others arrested and kidnapped 1 www.sn4hr.org - [email protected] Report Contents: - Introduction ................................................................................................3 - Report methodology ..................................................................................5 - Executive Summary ...................................................................................6 - Report Details ............................................................................................6 1. Government forces (army, security, local militias, foreign militias).........6 2. Kurdish Democratic Union forces ............................................................10 3. Extremist Groups .......................................................................................11 4. Armed Opposition Factions .......................................................................14 5. Unidentified Groups ...................................................................................15 - Recommendations .......................................................................................16 2 www.sn4hr.org - [email protected] SNHR is an independent, non-governmental, nonprofit, human rights organization that was founded in June 2011. SNHR is a Thursday 23 April 2015 certified source for the United Nation in all of its statistics. A- Introduction As the popular protests began in March 2011 the Syrian authorities realized the crucial role of the media in exposing their