Gradual Modifications of the Gagaku Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ryukyuanist a Newsletter on Ryukyu/Okinawa Studies No

The Ryukyuanist A Newsletter on Ryukyu/Okinawa Studies No. 67 Spring 2005 This issue offers further comments on Hosei University’s International Japan-Studies and the role of Ryukyu/Okinawa in it. (For a back story of this genre of Japanese studies, see The Ryukyuanist No. 65.) We then celebrate Professor Robert Garfias’s achievements in ethnomusicology, for which he was honored with the Japanese government’s Order of the Rising Sun. Lastly, Publications XLVIII Hosei University’s Kokusai Nihongaku (International Japan-Studies) and the Ryukyu/Okinawa Factor “Meta science” of Japanese studies, according to the Hosei usage of the term, means studies of non- Japanese scholars’ studies of Japan. The need for such endeavors stems from a shared realization that studies of Japan by Japanese scholars paying little attention to foreign studies of Japan have produced wrong images of “Japan” and “the Japanese” such as ethno-cultural homogeneity of the Japanese inhabiting a certain immutable space since times immemorial. New images now in formation at Hosei emphasize Japan’s historical “internationality” (kokusaisei), ethno-cultural and regional diversity, fungible boundaries, and demographic changes. In addition to the internally diverse Yamato Japanese, there are Ainu and Ryukyuans/Okinawans with their own distinctive cultures. Terms like “Japan” and “the Japanese” have to be inclusive enough to accommodate the evolution of such diversities over time and space. Hosei is a Johnny-come-lately in the field of Japanese studies (Hosei scholars prefer -

Glories of the Japanese Music Heritage ANCIENT SOUNDSCAPES REBORN Japanese Sacred Gagaku Court Music and Secular Art Music

The Institute for Japanese Cultural Heritage Initiatives (Formerly the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies) and the Columbia Music Performance Program Present Our 8th Season Concert To Celebrate the Institute’s th 45 Anniversary Glories of the Japanese Music Heritage ANCIENT SOUNDSCAPES REBORN Japanese Sacred Gagaku Court Music and Secular Art Music Featuring renowned Japanese Gagaku musicians and New York-based Hōgaku artists With the Columbia Gagaku and Hōgaku Instrumental Ensembles of New York Friday, March 8, 2013 at 8 PM Miller Theatre, Columbia University (116th Street & Broadway) Join us tomorrow, too, at The New York Summit The Future of the Japanese Music Heritage Strategies for Nurturing Japanese Instrumental Genres in the 21st-Century Scandanavia House 58 Park Avenue (between 37th and 38th Streets) Doors open 10am Summit 10:30am-5:30pm Register at http://www.medievaljapanesestudies.org Hear panels of professional instrumentalists and composers discuss the challenges they face in the world of Japanese instrumental music in the current century. Keep up to date on plans to establish the first ever Tokyo Academy of Japanese Instrumental Music. Add your voice to support the bilingual global marketing of Japanese CD and DVD music masterpieces now available only to the Japanese market. Look inside the 19th-century cultural conflicts stirred by Westernization when Japanese instruments were banned from the schools in favor of the piano and violin. 3 The Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies takes on a new name: THE INSTITUTE FOR JAPANESE CULTURAL HERITAGE INITIATIVES The year 2013 marks the 45th year of the Institute’s founding in 1968. We mark it with a time-honored East Asian practice— ―a rectification of names.‖ The word ―medieval‖ served the Institute well during its first decades, when the most pressing research needs were in the most neglected of Japanese historical eras and disciplines— early 14th- to late 16th-century literary and cultural history, labeled ―medieval‖ by Japanese scholars. -

Spring 2005 Curriculum

Spring 2005 Curriculum ART HISTORY AH 2125.01 Art History Documentary Series: “The Shock of the New” Jon Isherwood We will review the acclaimed BBC Art in Civilization documentary series by Robert Hughes, art critic and senior writer for Time magazine. The videos will be a starting point for discussion in regard to the major art movements in the 20th century, why they occurred and what cultural, social and political conditions were influencing these movements. Prerequisites: None. Credits: 1 Time: M 9 - 10am AH 2133.01 Introduction to Minimalism: Art, Dance, Music Laura Heon This course offers an overview of the American art movement of the 1960s and 70s called “Minimalism,” also known as “ABC Art” and “Primary Structures.” Characterized by extreme simplicity of form and a literal, objective approach, Minimalism gave rise to a vibrant exchange among the visual arts, dance, and music. Thus, this course will be divided evenly among visual artists (including Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Sol Lewitt, Dan Flavin), choreographers (Yvonne Rainer, Merce Cunningham, Trisha Brown) and the composers (La Monte Young, Phillip Glass, Terry Riley). It will include a trip to Dia:Beacon in nearby Beacon, NY, where an important collection of minimalist art is on view. The course will touch on the Abstract Expressionist movement, which laid the groundwork for Minimalism, as well as post-minimalist tendencies in the art of our time. Prerequisites: None. Credits: 4 Time: M 6:30 - 9:30pm - 1 - Spring 2005 Curriculum AH 4395.01 Art History Survey Seminar Andrew Spence This course will follow E.H. Gombrich’s The Story of Art. -

Hoiku Shoka and the Melody of the Japanese National Anthem Kimi Ga Yo

Hoiku shoka and the melody of the Japanese national anthem Kimi ga yo Hermann Gottschewski It is well known that Kimi ga yo君 が 代, although recognized as the Japanese national anthem by law only in 1999, was chosen in the summer of 1880 as a ceremonial piece for the navy. Its melody was composed by reijin1伶 人, i.e. members of the gagaku department of the court ministry宮 内 省 式 部 寮 雅 楽 課, and harmonized by Franz Eckert. It replaced an earlier piece by John William Fenton with the same text.2 Summe 1880 was Precisely when the newly founded Institute of Music(音 楽 取 調 掛)began the compilation of song books for elementary school (Shogaku shoka shu, 小 学 唱 歌 集)under the musical direction of Luther Whiting Mason, and many of the reijin took part in this new adventure. At about the same time, the reijin were engaged in the composition of hoiku shoka保 育 唱 歌, a collection of educational songs composed between 1877 and 1883 for the Tokyo Women's Normal School東 京 女 子 師 範 学 校and its afHliated kindergarten. While the songs of the Shogaku shoka shu mainly use Western melodies and are notated in Western staff system, the hoiku shoka are based on the music theory of gagaku and written in hakase墨 譜, the traditional notation for vocal pieces. Up to the present, the hoiku shoka have mainly been seen as an experiment in music education, which was abandoned when Mason's songs appeared. Indeed, historical sources show that the compilation of hoiku shoka stopped immediately after the reijin began to work with Mason. -

Society for Ethnomusicology 58Th Annual Meeting Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology 58th Annual Meeting Abstracts Sounding Against Nuclear Power in Post-Tsunami Japan examine the musical and cultural features that mark their music as both Marie Abe, Boston University distinctively Jewish and distinctively American. I relate this relatively new development in Jewish liturgical music to women’s entry into the cantorate, In April 2011-one month after the devastating M9.0 earthquake, tsunami, and and I argue that the opening of this clergy position and the explosion of new subsequent crises at the Fukushima nuclear power plant in northeast Japan, music for the female voice represent the choice of American Jews to engage an antinuclear demonstration took over the streets of Tokyo. The crowd was fully with their dual civic and religious identity. unprecedented in its size and diversity; its 15 000 participants-a number unseen since 1968-ranged from mothers concerned with radiation risks on Walking to Tsuglagkhang: Exploring the Function of a Tibetan their children's health to environmentalists and unemployed youths. Leading Soundscape in Northern India the protest was the raucous sound of chindon-ya, a Japanese practice of Danielle Adomaitis, independent scholar musical advertisement. Dating back to the late 1800s, chindon-ya are musical troupes that publicize an employer's business by marching through the From the main square in McLeod Ganj (upper Dharamsala, H.P., India), streets. How did this erstwhile commercial practice become a sonic marker of Temple Road leads to one main attraction: Tsuglagkhang, the home the 14th a mass social movement in spring 2011? When the public display of merriment Dalai Lama. -

Context and Change in Japanese Music Alison Mcqueen Tokita and David Hughes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SOAS Research Online ASHGATE RESEARCH 1 COMPANION Context and change in Japanese music Alison McQueen Tokita and David Hughes 1. What is ‘Japanese music’? Increasingly, the common view of Japan as a mono-cultural, mono-ethnic society, whether in modern or ancient times, is being challenged (Denoon et al. 1996). The category ‘Japan’ itself has been questioned by many (for example Amino 1992; Morris-Suzuki 1998). Amino insists that when discussing the past we should talk not about Japan or the Japanese people, but about people who lived in the Japanese archipelago. If Japan itself is not a solid entity, neither can its musical culture be reduced to a monolithic entity. If the apparently simple label ‘music of Japan’ might refer to any music to be found in Japan, then the phrase ‘music of the Japanese’ would cover any music played or enjoyed by the Japanese, assuming we can talk with confidence about ‘the Japanese’. The phrase ‘Japanese music’ might include any music that originated in Japan. This book would ideally cover all such possibilities, but must be ruthlessly selective. It takes as its main focus the musical culture of the past, and the current practices of those traditions as transmitted to the present day. A subsidiary aim is to assess the state of research in Japanese music and of research directions. The two closing chapters cover Western-influenced popular and classical musics respectively. At least, rather than ‘Japanese music’, we might do better to talk about ‘Japanese musics’, which becomes one justification for the multi-author approach of this volume. -

Shinto Gagaku Flyer.Pdf

Institute for Japanese Studies Lecture Series An Introduction to Shinto and Gagaku: Japan's Traditional Religion and Music Moriyasu Ito, Atsuki Katayama, Takanaga Tsutsumi Meiji Jingu Shrine (Tokyo, Japan) Monday, September 24, 2018 Lecture & Performance 5:15-7:00pm Doors Open at 5:00pm Jennings Hall 001 (1735 Neil Ave.) Many in contemporary Japan enjoy the occasions of Halloween and Christmas while the patterns of their daily life honor the traditions of Buddhism and Shintoism. Indeed, Japan is best known to the rest of the world for its Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, especially in the ancient capitals of Kyoto and Nara, together with cultural legacies such as Zen practices, gardens and other forms of art. Today’s presentation will focus on Shinto and gagaku music that goes with Shinto ceremonies. Shinto is Japan’s indigenous religion that long predates the arrival of Buddhism in the sixth century via China and Korea. To this day, a vast majority of Japanese people visit Shinto shrines on seasonal and auspicious occasions throughout the year. Unlike most organized religions, however, Shinto has no original founder, no formal doctrines, and no holy scriptures. One of the best ways to learn about Shinto is to attend a presentation, and to experience some aspects of it first-hand, by those who practice it. For today’s presentation, three priests from Meiji Jingu¸ one of the best known shrines to both Japanese and foreigners, will discuss the relationship among Shinto, nature, and the way of Japanese life. They will also perform gagaku, Japan’s traditional music, which can transport the audience in the echo of time and space from the ancient to the present. -

Japan's Nineteen Unesco World Heritage Sites

Feature JAPANESE WORLD HERITAGE JAPAN’S NINETEEN UNESCO 8 WORLD HERITAGE SITES In 1993, Horyu-ji, Himeji Castle, Shirakami Sanchi and Yakushima were registered as Japan’s first four UNESCO World Heritage sites—a list that has now expanded to include fifteen World Cultural Heritage sites and four World Natural Heritage sites. Japan further boasts twenty-two items on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage List, which aims to protect aspects of intangible culture such as traditional music, dance, theater and industrial arts. ITSUKUSHIMA SHINTO SHRINE Location 13 4 Hiroshima Prefecture 1996 Year Inscribed Together with the surrounding sea and 4 the primeval forests of nearby Mount 16 19 Misen, the entire shrine complex has been 17 2 6 registered as a World Heritage Site. 5 10 © MINISTRY OF THE ENVIRONMENT GOVERNMENT OF JAPAN 18 SHIRAKAMI-SANCHI Aomori Prefecture, Akita 9 19 14 17 19 Prefecture 1993 12 Hosting a diverse variety of flora and fauna, the area 7 1 is exemplary of the forests of Siebold’s beech trees 19 8 9 that flourished in East Asia immediately following 3 12 the last ice age. 5 11 15 HISTORIC MONUMENTS OF ANCIENT NARA Nara Prefecture 1998 These monuments embody the cultural 1 heritage of the Nara Period, during which the foundations of Japan as a nation were established. Architectural elements such HISTORIC MONUMENTS OF ANCIENT KYOTO as Todai-ji Temple and natural landscapes, [KYOTO, UJI AND OHTSU CITIES] including Kasugayama Primeval Forest, form Kyoto Prefecture, Shiga Prefecture 1994 a synergistic environment. From its foundation by Emperor Kanmu in 794 AD, BUDDHIST MONUMENTS IN THE HORYU-JI Kyoto flourished as the imperial capital of Japan for a 10 AREA Nara Prefecture 1993 thousand years. -

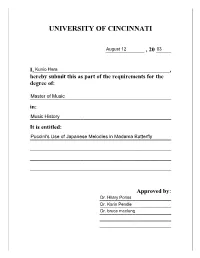

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ PUCCINI’S USE OF JAPANESE MELODIES IN MADAMA BUTTERFLY A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Kunio Hara B.M., University of Cincinnati, 2000 Committee Chair: Dr. Hilary Poriss ABSTRACT One of the more striking aspects of exoticism in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly is the extent to which the composer incorporated Japanese musical material in his score. From the earliest discussion of the work, musicologists have identified many Japanese melodies and musical characteristics that Puccini used in this work. Some have argued that this approach indicates Puccini’s preoccupation with creating an authentic Japanese setting within his opera; others have maintained that Puccini wanted to produce an exotic atmosphere -

Court Music by Shiba Sukeyasu

JAPANESE MIND Japan’s Ancient Court Music By Shiba Sukeyasu Photos: Music Department, Imperial Household Agency Origin of Gagaku : Ancient Gala Concert A solemn ceremony was held at Todai-ji – a majestic landmark Buddhist temple – in the ancient capital of Nara 1,255 years ago, on April 9 in 752, to endow a newly completed Great Buddha statue with life. The ceremony was officiated by a high Buddhist priest from India named Bodhisena (704-760), and attended by the Emperor, members of the Imperial Family, noblemen and high priests. Thousands of pious people thronged the main hall of the temple that houses the huge Buddha image to “Gagaku” is performed by members of the Music Department of the express their joy in the event. Imperial Household Agency. Traditionally, kakko (right in the front row) On the stage set up in the foreground is always played by the oldest band member. of the hall, a gala celebratory concert was staged and performing arts from Tang music that he aspired to learn the instruments various parts of Asia were introduced. music in Tang. Legend has it that his were three wind Outstanding among them was Chinese wish was finally granted in 835 when he instruments – music called Togaku (music of the Tang was aged 103. His willpower was sho (mouth organ), hichiriki (oboe) and Dynasty). Clad in colorfully unruffled by his old age and he returned ryuteki (seven-holed flute) –, two string embroidered gorgeous silk costumes, to Japan after learning music and instruments – biwa (lute) and gakuso Chinese musicians played 18 different dancing for five years. -

On the Tonal Unity in the Melodies of Japanese Folk-Music in Modern Times

On the tonal unity in the melodies of Japanese folk-music in modern times 著者 Aizawa Mutuo journal or Tohoku psychologica folia publication title volume 11 number 1-2 page range 1-8 year 1944-05-31 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10097/00127292 On the tonal unity in the melodies of Japanese folk-music in modern times1 By Mutuo Aizawa (,m 1" 11t 9l!: ~l (Hukusima Normal School) Contents 1. On the variety of Japanese music . 2. Problem .. 2 3. Experiment . 4 4. Results ............ 7 5. Summary of results and conclusions 8 1. On the variety of Japanese music This article is the report of a study on the musical scales of our folk-music. It may be proper, however, to consider briefly Japanese music in general before we proceed to the explanation of our problem. To-day, we Japanese are enjoying various kinds of music. It would not be too much to say that we enjoy all of the eastern and all of the western music. We had our own music from the earliest times of our history. Since the culture of the Asiatic Continent entered our country, musical compositions from Korea, from China, from Manchuria, from Annam, and even from India, Central Asia were performed, and new varieties of performance of our ancient music and new compositions were born under their influence. Various kinds of musical instruments were added to our original ones, too. The musical compositions of our an- I This research is a part of one which was made in the Psychological Laboratory of Tohoku Imperial University under the support of Nippon Gakuzyutu Sinkokwai. -

Musical Taiwan Under Japanese Colonial Rule: a Historical and Ethnomusicological Interpretation

MUSICAL TAIWAN UNDER JAPANESE COLONIAL RULE: A HISTORICAL AND ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION by Hui‐Hsuan Chao A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Professor Joseph S. C. Lam, Chair Professor Judith O. Becker Professor Jennifer E. Robertson Associate Professor Amy K. Stillman © Hui‐Hsuan Chao 2009 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Throughout my years as a graduate student at the University of Michigan, I have been grateful to have the support of professors, colleagues, friends, and family. My committee chair and mentor, Professor Joseph S. C. Lam, generously offered his time, advice, encouragement, insightful comments and constructive criticism to shepherd me through each phase of this project. I am indebted to my dissertation committee, Professors Judith Becker, Jennifer Robertson, and Amy Ku’uleialoha Stillman, who have provided me invaluable encouragement and continual inspiration through their scholarly integrity and intellectual curiosity. I must acknowledge special gratitude to Professor Emeritus Richard Crawford, whose vast knowledge in American music and unparallel scholarship in American music historiography opened my ears and inspired me to explore similar issues in my area of interest. The inquiry led to the beginning of this dissertation project. Special thanks go to friends at AABS and LBA, who have tirelessly provided precious opportunities that helped me to learn how to maintain balance and wellness in life. ii Many individuals and institutions came to my aid during the years of this project. I am fortunate to have the friendship and mentorship from Professor Nancy Guy of University of California, San Diego.