The Wonder Year Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

February 27, 1989

^m ^m ^ppp«ppp"f p«p 1^ mmmm* :':^<g >tf**^ -j****© :>fW:?;** ^¾¾¾ BH^KJLL-i^A—J i .•Jv^U'-t ••: aa^^-i^^rr-i^'.W^.n^tf-:-'^ 1 , Volume24 NumDer 73 Monday, February 27,1989 - Westland, (yllfchlgan 46 Pages Twenty-five cents .019S9 Siby **n CoovhunJaUon* CcrporHka. AU W4IU Kauvvt. • i e Hi W.(*S ;-:,:5'i &J*M- -:\ Man, 19, gets life in girl's death By Tedd 8chnelder said."And years down the road her status la's death and whether he sexually assaulted Some7 of the victim's clothes were found In staff writer won't be changing either." her while she was stiil alive '. nearby bushes, and her purse was found hldden- Defense attorney Charles Campbell did not In an earlier statement, signed by the de in brush about 116 yards from the body, court 4! '*•*';£r&f 'J,- A Westland man was sentenced to life in return phone calls to discuss the sentence. fendant and admitted as evidence in the trial, testimony revealed. i prison with no parole Thursday for the August ZIMMERLA, WHO died from a skull frac Emerson said he hit Zimmerla In the back of placM beating death of a John Glenn High School girl. ture according to the Wayne County medical the head several times with a large rock while EMERSON HAD known Zimmerla for about Ronald O'Neal Emerson, 19, was found examiner, would have been a junior at John the two were arguing along the banks of the six weeks at the time of the murder, according and face* guilty by a Wayne County Circuit Court jury Glenn last fall. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Nikki Caldwell Head Coach, 3Rd Season Tennessee ’94

The Basketball Staff Nikki Caldwell Head Coach, 3rd Season Tennessee ’94 Nikki Caldwell, recognized as one of the nation’s top assistant coaches during stints at Tennessee and at Virginia, is putting together an impressive head coaching re- sume as well as she prepares to begin her third year in charge of the Bruin program after being named the Pac-10 Conference Coach of the Year for 2009-10. Her second Bruin team finished with 25 wins, the fourth-most in school history, and advanced to the second round of the NCAA Tournament. After a mid-January setback in conference play, the Bruins lost only to NCAA run- ner-up Stanford (twice) and No. 4-ranked Nebraska, two No. 1 NCAA Tournament seeds, while winning 15 of its last 18 contests. The squad matched the school mark for conference wins in a season with 15, while taking second in the Pac-10. It also set a school record by limiting op- ponents to 57.5 points per game. Her 2009 Bruin team completed her inaugural campaign with a 19-12 record and tied for fourth place in the Pac-10 Conference. The 19 wins matched the number for the 10th-best total in school history. The total of 13 home wins tied for the second-most in school annals. In addition, for the first time since the 1986-87 season, the Bruins won as many as nine pre-season, non-conference games. Caldwell and staff then proceeded to haul in the 14th-ranked recruiting class in the nation, headlined by McDonald’s All-American Markel Walker from Philadelphia, PA. -

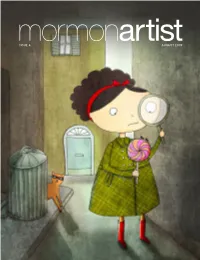

ISSUE 6 Artistaugust 2009 Editor-In-Chief Mormonartist Ben Crowder Covering the Latter-Day Saint Arts World Managing Editor Katherine Morris

mormonISSUE 6 artistAUGUST 2009 EDitOR-IN-CHieF mormonartist Ben Crowder COVERING THE LatteR-DAY saiNT ARts WORLD MANagiNG EDitOR Katherine Morris seCtiON EDitORS Mormon Artist is a quarterly magazine Literature: Katherine Morris published online at MORMONARtist.Net Visual Arts: Megan Welton Music & Dance: Meridith Jackman issn 1946-1232. Copyright © 2009 Mormon Artist. Film: Meagan Brady Theatre: Annie Mangelson All rights reserved. COPY EDitORS All reprinted pieces of artwork copyright their respective owners. Annie Mangelson Jennifer McDaniel Front cover artwork courtesy Cambria Evans Christensen. Katherine Morris Back cover photograph courtesy Greg Deakins. Meagan Brady Megan Welton Paintings on pages vii, viii courtesy J. Kirk Richards. Meridith Jackman Photographs on pages 1–4, 6–9 courtesy Greg Deakins. Photographs on pages 10, 11, 15 courtesy Cambria Evans Christensen. THis issue Artwork on pages 12–14 courtesy Cambria Evans Christensen. WRiteRS Amelia Chesley Photographs on pages 16, 18–21 courtesy Perla Antoniak. Amy Baugher David Layton Photographs on pages 22–24 courtesy Debra Fotheringham. Mahonri Stewart Menachem Wecker Photographs on pages 26, 27, 29 courtesy April Bladh. PHOTOGRAPHERS Greg Deakins “Catch” reprinted with permission from Patrick Madden. Want to help out? See: Design by Ben Crowder. http://mormonartist.net/volunteer CONtaCT us WEB MORMONARtist.Net EMaiL [email protected] taBLE OF CONteNts Editor’s Note iv Submission Guidelines v ARtiCLE Are Scholars and Museums vi Ignoring Mormon Artists? BY MENACHEM WECKER LiteRatuRE Patrick Madden 1 BY AMELia CHesLEY Catch 5 BY PatRICK MADDEN Rick Walton 6 BY DAVID LAYTON VisuaL & APPLieD ARts Cambria Evans Christensen 10 BY MAHONRI steWART Perla Antoniak 18 BY AMY BaugHER MusiC & DANCE Debra Fotheringham 24 BY DAVID LAYTON FILM & THeatRE Danor Gerald 28 BY MAHONRI steWART EDitOR’S NOte t’s hard to believe, but Mormon Artist is now one year old. -

Audio + Video 11/21/11 Audio & Video Recap

NEW RELEASES WEA.COM ISSUE 24 NOVEMBER 22 + NOVEMBER 29, 2011 LABELS / PARTNERS Atlantic Records Asylum Bad Boy Records Bigger Picture Curb Records Elektra Fueled By Ramen Nonesuch Rhino Records Roadrunner Records Time Life Top Sail Warner Bros. Records Warner Music Latina Word AUDIO + VIDEO 11/21/11 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ORDERS ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPCSEL # SRP QTY DUE ARJONA, RICARDO Grandes Exitos LAT CD 881410007427 528629 $11.98 11/1/11 Blues (5LP 180 Gram Vinyl Box CLAPTON, ERIC REP CD 881410007328 528599 $11.98 10/26/11 Set)(w/Litho) CLOUD CONTROL Bliss Release TNO CD 881410007526 529522 $11.98 11/1/11 COMMON The Dreamer, The Believer TCM CD 881410007120 529038 $11.98 11/1/11 COMMON The Dreamer, The Believer (Amended) TCM CD 881410006321 529517 $11.98 11/1/11 DEATH CAB FOR Keys and Codes Remix EP ATL CD 881410006420 529443 $11.98 11/1/11 CUTIE DEFTONES White Pony (2LP) MAV CD 881410006222 524901 $11.98 11/1/11 NICKELBACK Here And Now RRR A 656605793214 177092 $16.98 11/1/11 Last Update: 10/03/11 For the latest up to date info on this release visit WEA.com. ARTIST: Ricardo Arjona TITLE: Grandes Exitos Label: LAT/Warner Music Latina Config & Selection #: CD 528629 Street Date: 11/22/11 Order Due Date: 11/02/11 UPC: 825646669851 Box Count: 30 Unit Per Set: 1 SRP: $13.98 Alphabetize Under: A File Under: Latin - Pop TRACKS Compact Disc 1 01 Acompaname a estar solo 10 Realmente no estoy tan solo (Album) 02 Senora de las cuatro decadas (Album) 11 Dame (Album) 03 Sin Ti Sin Mi (Album) 12 Mujeres (Album) 04 Te conozco (Album) 13 Minutos (Album) -

Exclusives April 16, 2011

NEw RElEasEs WEA.CoM ExCLuSivES APRiL 16, 2011 LABELS / PARTNERS Atlantic Records Asylum Bad Boy Records Bigger Picture Curb Records Elektra Fueled By Ramen Nonesuch Rhino Records Roadrunner Records Time Life Top Sail Warner Bros. Records Warner Music Latina Word ExclusivEs audio + vidEo 4/16/11 Record Store Day Exclusive Releases *Click on the Artist Names to be taken directly to the Sell Sheet. Click on the Artist Name in the Order Due Date Sell Sheet to be taken back to the Recap Page Street Date God Of Love (RSD MAV A-527297 BAD BRAINS Exclusive)(w/Bonus 7") $24.98 4/16/11 3/23/11 Ripple (Picture Disc)(RSD WB S-527415 BUILT TO SPILL Exclusive) $11.98 4/16/11 3/23/11 CD- Appendage (Web, Tour and ATL 526445 CIRCA SURVIVE RSD Exclusive) $4.98 4/16/11 3/23/11 Appendage (Oxblood Colored Vinyl)(Web, Tour and RSD ATL A-527016 CIRCA SURVIVE Exclusive) $10.98 4/16/11 3/23/11 Atlantic Records Presents: DEATH CAB FOR Death Cab for Cutie In Living ATL S-527399 CUTIE Stereo! (RSD Exclusive) $3.98 4/16/11 3/23/11 WB A-527409 DEFTONES Covers (RSD Exclusive) $22.98 4/16/11 3/23/11 Riders On The Storm(Stereo)/Riders On The RHI S-527487 DOORS, THE Storm(Mono) (RSD Exclusive) $6.98 4/16/11 3/23/11 Heady Nuggs: The First 5 FLAMING LIPS, Warner Bros. Records 1992- WB A-527227 THE 2002 (RSD Exclusive) $124.98 4/16/11 3/23/11 Grateful Dead (Mono)(180 RHI A-1689 GRATEFUL DEAD Gram Vinyl)(RSD Exclusive) $24.98 4/16/11 3/23/11 Don't Want To Know If You Are GREEN DAY/ Lonely (Orange Vinyl)(RSD WB S-527424 HUSKER DU Exclusive) $6.98 4/16/11 3/23/11 Risin' Outlaw -

A Man's Face in the Sky Instead of the Sun

A MAN’S FACE IN THE SKY INSTEAD OF THE SUN By ©2012 DANIEL ROLF Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Thomas D. Lorenz ________________________________ Joshua Cohen ________________________________ Robert Glick Date Defended: April 10, 2012 The Thesis Committee for DANIEL ROLF certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: A MAN’S FACE IN THE SKY INSTEAD OF THE SUN ________________________________ Chairperson Thomas D. Lorenz Date approved: April 10, 2012 ii ABSTRACT This is Daniel Rolf’s thesis. It consists of short, interrelated fictions that work together as a whole. iii Just lie back, God. Let me do this. 1 To my real son, This is a book. Books are long, or at least several put together can be. I do not know what this one will be, but it's for you. It's about me. It has to be or it wouldn't be true. I do not know you. Not that I feel I do not know you. You are what you are to me. You have flesh and clothes when I think of you. I watched you grow. It feels true. But the lie of it always has an arm over my shoulders in fellowship. When I was a child I heard an uncle tell my third dad in a moving pickup he wished he had done some things different. My dad said: “Yeah”. That is what I feel when I think of you. -

The BET AWARDS '11 Belonged to Chris Brown with His Mind Blowing Performances, Collaborations, and Wins for Best Male Artist, Co

The BET AWARDS '11 Belonged to Chris Brown With His Mind Blowing Performances, Collaborations, and Wins for Best Male Artist, Coca-Cola Viewer's Choice, Best Collaboration, and Video of the Year Awards CEE LO GREEN CHANNELS HIS INNER PATTI LABELLE IN FULL COSTUME DURING HER TRIBUTE PERFORMANCE FOR THE LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD JUSTIN BIEBER FLIRTS WITH NICKI MINAJ ON STAGE ALICIA KEYS PERFORMS NEW SONG "TYPEWRITER" AND SHARES STAGE WITH BRUNO MARS AND RICK ROSS STEVE HARVEY INSPIRES THE AUDIENCE AS THE HUMANITARIAN AWARD RECIPIENT NEW YORK, June 27, 2011 - The hilarious Kevin Hart kept the crowd laughing out loud as a Hollywood House Husband during the BET AWARDS '11 opening act with Bobby Brown, Jermaine Dupri, Anthony Anderson, Nelly, and Nick Cannon. Chris Brown's powerful performance medley of "She Ain't You," "Look at Me Now," and "Paper Scissor Rock" illustrated just why he was named the 2011 Best Male R&B Artist, Video of the Year, Best Collaboration, and Coca-Cola Viewer's Choice Award winner when he took to the stage in two performances collaborating with Busta Rhymes and Big Sean. Later, a precocious Justin Bieber propositioned Nicki Minaj on stage when he said, "I'm all grown up now. I turn 18 next year so...what's up?" (Logo: http://photos.prnewswire.com/prnh/20070716/BETNETWORKSLOGO ) Legendary songstress and diva extraordinaire Patti LaBellewas the recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award and her tribute was a performance unlike anything ever seen before. Beginning with a special introduction from another musical icon, -

Songs by Artist

Songs By Artist Artist Song Title Disc # Artist Song Title Disc # (children's Songs) I've Been Working On The 04786 (christmas) Pointer Santa Claus Is Coming To 08087 Railroad Sisters, The Town London Bridge Is Falling 05793 (christmas) Presley, Blue Christmas 01032 Down Elvis Mary Had A Little Lamb 06220 (christmas) Reggae Man O Christmas Tree (o 11928 Polly Wolly Doodle 07454 Tannenbaum) (christmas) Sia Everyday Is Christmas 11784 She'll Be Comin' Round The 08344 Mountain (christmas) Strait, Christmas Cookies 11754 Skip To My Lou 08545 George (duet) 50 Cent & Nate 21 Questions 00036 This Old Man 09599 Dogg Three Blind Mice 09631 (duet) Adams, Bryan & When You're Gone 10534 Twinkle Twinkle Little Star 09938 Melanie C. (christian) Swing Low, Sweet Chariot 09228 (duet) Adams, Bryan & All For Love 00228 (christmas) Deck The Halls 02052 Sting & Rod Stewart (duet) Alex & Sierra Scarecrow 08155 Greensleeves 03464 (duet) All Star Tribute What's Goin' On 10428 I Saw Mommy Kissing 04438 Santa Claus (duet) Anka, Paul & Pennies From Heaven 07334 Jingle Bells 05154 Michael Buble (duet) Aqua Barbie Girl 00727 Joy To The World 05169 (duet) Atlantic Starr Always 00342 Little Drummer Boy 05711 I'll Remember You 04667 Rudolph The Red-nosed 07990 Reindeer Secret Lovers 08191 Santa Claus Is Coming To 08088 (duet) Balvin, J. & Safari 08057 Town Pharrell Williams & Bia Sleigh Ride 08564 & Sky Twelve Days Of Christmas, 09934 (duet) Barenaked Ladies If I Had $1,000,000 04597 The (duet) Base, Rob & D.j. It Takes Two 05028 We Wish You A Merry 10324 E-z Rock Christmas (duet) Beyonce & Freedom 03007 (christmas) (duets) Year Snow Miser Song 11989 Kendrick Lamar Without A Santa Claus (duet) Beyonce & Luther Closer I Get To You, The 01633 (christmas) (musical) We Need A Little Christmas 10314 Vandross Mame (duet) Black, Clint & Bad Goodbye, A 00674 (christmas) Andrew Christmas Island 11755 Wynonna Sisters, The (duet) Blige, Mary J. -

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Literary

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of The Study Literary text contains a potentiality for tranforming the whole system that it embodies and that has produced it. Literary text is able to subvert the linguistic system it inherits, it doest not merely exhibit the characteristic form of the language which contains it, it also extends and modifies that language1 Literature is a canon which consists of those works in language by which a community defines itself through the course of its history. It include works primarily artistic and also those whose aesthetic qualities are only secondary2. Literature is a word in the English language; like all words, literary texts. It is used by perhaps millions of speakers, speakers who come from vastly different backgrounds and who have quite divergent personal experiences with, and views on, literary text3. The very word “music” comes from the Greek word mousikos, meaning “of the muses” (the Greek goddesses who inspired poets, painters, 1 Sanusi, Ibrahim Chinade,” Structuralism as a Literary Theory: An Overview,” 124- 131(March, 2012), 128. 2 Jim Meyer, “What is Literature?” A Definiion Based on Prototypes,” Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguisic,(Volume 411), 2 (July, 1997), 3. 3 Ibid, 2. 2 musicans, and so forth)4. Music is so naturally united with us that we cannot be free from it even if we so desired. Music has performed an important stages of a person‟s life with specific types or pieces of music. There are birth songs, birthday songs, holiday songs, retirement songs, and even death songs. Music‟s influence is so prevalen that, to this day, most of us remember songs that played it our most important moments.5 Music„s intimacy is so powerful that it seduces us.