Recent Militant Violence Against Adivasis in Assam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIST of POST GST COMMISSIONERATE, DIVISION and RANGE USER DETAILS ZONE NAME ZONE CODE Search

LIST OF POST GST COMMISSIONERATE, DIVISION AND RANGE USER DETAILS ZONE NAME GUW ZONE CODE 70 Search: Commission Commissionerate Code Commissionerate Jurisdiction Division Code Division Name Division Jurisdiction Range Code Range Name Range Jurisdiction erate Name Districts of Kamrup (Metro), Kamrup (Rural), Baksa, Kokrajhar, Bongaigon, Chirang, Barapeta, Dhubri, South Salmara- Entire District of Barpeta, Baksa, Nalbari, Mankachar, Nalbari, Goalpara, Morigaon, Kamrup (Rural) and part of Kamrup (Metro) Nagoan, Hojai, East KarbiAnglong, West [Areas under Paltan Bazar PS, Latasil PS, Karbi Anglong, Dima Hasao, Cachar, Panbazar PS, Fatasil Ambari PS, Areas under Panbazar PS, Paltanbazar PS & Hailakandi and Karimganj in the state of Bharalumukh PS, Jalukbari PS, Azara PS & Latasil PS of Kamrup (Metro) District of UQ Guwahati Assam. UQ01 Guwahati-I Gorchuk PS] in the State of Assam UQ0101 I-A Assam Areas under Fatasil Ambari PS, UQ0102 I-B Bharalumukh PS of Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Gorchuk, Jalukbari & Azara PS UQ0103 I-C of Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Nagarbera PS, Boko PS, Palashbari PS & Chaygaon PS of Kamrup UQ0104 I-D District Areas under Hajo PS, Kaya PS & Sualkuchi UQ0105 I-E PS of Kamrup District Areas under Baihata PS, Kamalpur PS and UQ0106 I-F Rangiya PS of Kamrup District Areas under entire Nalbari District & Baksa UQ0107 Nalbari District UQ0108 Barpeta Areas under Barpeta District Part of Kamrup (Metro) [other than the areas covered under Guwahati-I Division], Morigaon, Nagaon, Hojai, East Karbi Anglong, West Karbi Anglong District in the Areas under Chandmari & Bhangagarh PS of UQ02 Guwahati-II State of Assam UQ0201 II-A Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Noonmati & Geetanagar PS of UQ0202 II-B Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Pragjyotishpur PS, Satgaon PS UQ0203 II-C & Sasal PS of Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Dispur PS & Hatigaon PS of UQ0204 II-D Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Basistha PS, Sonapur PS & UQ0205 II-E Khetri PS of Kamrup (Metropolitan) District. -

South Asia Conflict Monitor

SOUTH ASIA CONFLICT MONITOR Volume 1, Number 9, February 2014 INDIA Is the CPI (Maoist) Loosing Ground? ate? Country Round up Bangladesh 8 India 10 Maldives 13 Nepal 14 Pakistan 15 Sri Lanka 17 The South Asia Conflict Monitor (SACM ) aims to provide in-depth analyses, country briefs, summary sketches of important players and a timeline of major events on issues relating to armed conflicts, insurgencies and terrorism. It also aims to cover the government’s strategies on conflict resolution and related policies to tackle these risks and crises. The South Asia Conflict Monitor is a monthly bulletin designed to provide quality information and actionable intelligence for the policy and research communities, the media, business houses, law enforcement agencies and the general reader by filtering relevant open source information and intelligence gathered from the ground contacts and sources The South Asia Conflict Monitor is scheduled to be published at the beginning of each calendar month, assessing events and developments of the previous month. Editor: Animesh Roul (Executive Director, Society for the Study of Peace and Conflict, New Delhi). Consulting Editor: Nihar R. Nayak (Associate Fellow, Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi) About SSPC The Society for the Study of Peace and Conflict (SSPC) is an independent, non-profit, non- partisan research organization based in New Delhi, dedicated to conduct rigorous and comprehensive research, and work towards disseminating information through commentaries and analyses on a broad spectrum of issues relating to peace, conflict and human development. SSPC has been registered under the Societies Registration Act (XXI) of 1860. The SSPC came into being as a platform to exchange ideas, to undertake quality research, and to ensure a fruitful dialogue. -

Deputy Commissioner Sonitpur, Tezpur

LIST OF WINNING CANDIDATES INCLUDING CONTESTING CANDIDATES OF WARD MEMBER,PANCHAYAT ELECTION,2018 SONITPUR DISTRICT Political party wise total vote Republi Socdialist Unity Represe Winning Name of ZPC Name of GP Name of WARD Total Total Total Total Sanmilita Total kan Total Centre of Total Total Total nting AGP BJP INC AIUDF IND Others Candidte Vote Vote Vote Vote Gana Shakti Vote Party of Vote India(Communi Vote Vote Vote Party India(A) st) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 13/1 Missmari 1.Jia Gabharu W/N-1 Begenajuli Malaoi Hemram 272 Hemraj Sarmah 243 Malaoi Hemram BJP 13/1 Missmari 1.Jia Gabharu W/N-2 No 2 Naharani Padma Devi 292 Manoj Bhattarai 294 Manoj Bhattarai INC 13/1 Missmari 1.Jia Gabharu W/N-3 No 3 Dighaljuli Ashima Das 303 Manika Rai 176 Ashima Das BJP 13/1 Missmari 1.Jia Gabharu W/N-4 No 4 Jiagabharu "Ka" Binaka Kasla 127 Ahida Begum 224 Ahida Begum INC 13/1 Missmari 1.Jia Gabharu W/N-5 No 5 Jiagabharu 'Kha' Babul Deka 276 Sunil Kandulana 197 Babul Deka BJP 13/1 Missmari 1.Jia Gabharu W/N-6 No 6 Rikamari Anjana Kharia 320 Ani Nag 284 Anjana Kharia BJP 13/1 Missmari 1.Jia Gabharu W/N-7 No 7 Kathalguri Lakhiram Orang 121 Jiban Hemram 89 Lakhiram Orang BJP 13/1 Missmari 1.Jia Gabharu W/N-8 Jiagabharu 'Ga' Bogi Koch 213 Ruplekha Das 167 Bogi Koch BJP Ranu 13/1 Missmari 1.Jia Gabharu W/N-9 Tantsal Ranu Biswakarma 104 Dipa Biswakarma 80 BJP Biswakarma 13/1 Missmari 1.Jia Gabharu W/N-10 Nepali Basti Nitu Sarmah 398 Santana Das 222 Nitu Sarmah BJP Athnasius 13/1 Missmari 2.Missamari W/N-1Dhankhona 'Kha' Jiban Surin 229 Athnasius -

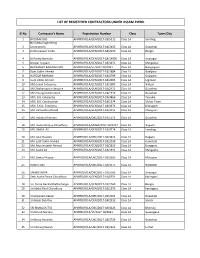

Contractor List.Xlsx

LIST OF REGISTERED CONTRACTORS UNDER ASSAM PWRD Sl No Contractor’s Name Registration Number Class Town/City 1 SRI DIPAK DAS APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/5311 Class 1A Sorbhog M/S Deka Engineering 2 Construction APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2452 Class 1A Guwahati 3 Sri Dhaneswar Kalita APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2150 Class 1A Rangia 4 Sri Prodip Bordoloi APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/14900 Class 1A Sivasagar 5 Anowar Hussain APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/3671 Class 1A Mangaldoi 6 DHANANJAY BASUMATARY APWRD/R/1A/ST/2017‐18/4814 Class 1A Bongaigaon 7 Giyas Uddin Ahmed APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2684 Class 1A Goalpara 8 HAFIZUR RAHMAN APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/4799 Class 1A Goalpara 9 Isam Uddin Ahmed APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2005 Class 1A Jagiroad 10 M/S Jonali Enterprise APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2987 Class 1A Nalbari 11 M/S Mahamaya Enterprise APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2471 Class 1A Guwahati 12 M/S Young Construction APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/1915 Class 1A Guwahati 13 M/S. B.B. Enterprise APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/3866 Class 1A Tinsukia 14 M/S. B.K. Construction APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/1574 Class 1A Silchar Town 15 M/S. S.K.D. Enterprise APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2373 Class 1A Dibrugarh 16 Md. Alimuddin Ahmed APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2015 Class 1A Changsari 17 Md. Habibur Rahman APWRD/R/1A/OBC/2017‐18/1171 Class 1A Guwahati 18 Md. -

LAC No. Name of LAC Electoral Registration Officer Postal Address

LAC No. Name of LAC Electoral Registration Officer Postal Address O/O the Circle Officer, Ratabari Revenue 1 Ratabari (SC) Circle Officer, R.K. Nagar Circle, P.O.- Ratabari Dist- Karimganj Pin- 788735 O/O the Circle Officer, Patharkandi 2 Patharkandi Circle Officer, Patharkandi Revenue Circle Revenue Circle, P.O.- Patharkandi, Dist- Karimganj Pin- 788724 O/O the Deputy Commissioner, Karimganj, 3 Karimganj North Election Officer, Karimganj P.O.- Karimganj Dist- Karimganj Pin- 788710 O/O the Circle Officer, Nilambazar 4 Karimganj South Circle Officer, Nilambazar Revenue Circle Revenue Circle, P.O.- Karimganj Dist- Karimganj Pin- 788710 O/O the Circle Officer, Badarpur Rev. 5 Badarpur Circle Officer, Badarpur Revenue Circle Circle, P.O.- Badarpur Dist- Karimganj Pin- 788806 O/O the Circle Officer,Hailakandi Rev. 6 Hailakandi Circle Officer, Hailakandi Revenue Circle Circle, P.O.- Hailakandi Dist- Hailakandi Pin- 788152 O/O the Assistant Settlement Officer, 7 Katlicherra Assistant Settlement Officer, Katlicherra Katlichera, P.O - Katlichera, Dist- Hailakandi Pin- 788161 O/O the Circle Officer,Algapur Rev. Circle, 8 Algapur Circle Officer, Algapur Revenue Circle P.O.- Algapur Dist- Hailakandi Pin- 788150 O/O the Deputy Commissioner, Cachar, 9 Silchar Election Officer, Silchar P.O.- Silchar Dist- Cachar Pin- 788001 O/O the Circle Officer,Sonai Rev. Circle, 10 Sonai Circle Officer, Sonai Revenue Circle P.O.- Sonai Dist- Cachar Pin- 788001 O/O the Circle Officer,Silchar Rev. Circle, 11 Dholai (SC) Circle Officer, Silchar Revenue Circle P.O.- Dholai Dist- Cachar Pin- 788114 O/O the Circle Officer,Udharbond Rev. 12 Udharbond Circle Officer, Udharbond Revenue Circle Circle, P.O.- Udharbond Dist- Cachar Pin- 788030 O/O the Sub Divisional Officer (C), 13 Lakhipur Sub Divisional Officer (C), Lakhipur Lakhipur, P.O.- Lakhipur Dist.- Cachar Pin- 788103 O/O the Deputy Commissioner, Cachar, 14 Barkhola Additional Deputy Commissioner-III, Cachar, Silchar P.O.- Silchar Dist- Cachar Pin- 788001 O/O the Circle Officer,Katigorah Rev. -

Assam: Documents

CHARGE SHEET (Under Section 173 CrPC) IN THE COURT OF NIA SPECIAL JUDGE, AIZAWL 1 Name of the Branch NIA Branch Office, Guwahati, Assam FIR No. year and date NIA case no. RC-03/2014/NIA-GUW dated 22.07.2014 arising out of FIR No. 155/2014 dated 03.05.2014 of Gossaigaon PS, Kokrajhar district, Assam. 2 Final Report / Charge Sheet No. 01/2017 3 Date 14.03.17 4 Sections of Law Sections 448,457,302, 307, 326, 324, 427, (in FIR) 34 of IPC r/w Section 27 of Arms Act and Sections 16, 18, 20 UA(P) Act, 1967 5 Type of Final Report Charge sheet 6 If Final Report Un- Not Applicable occurred/ false/ Mistake of fact or law/Civil Nature/ Non-Cognizable 7 If Charge-sheeted: First Supplementary Charge sheet Original / Supplementary CHARGE SHEET: NIA CASE NO. RC-03/2014/NIA-GUW Page 1 8 Name of Investigating T J Singh, Addl. Superintendent of Police, Officer NIA Branch office, Guwahati, Assam 9 Name of the XXXXXXXX and 2 others of Vill: Complainant/ Informant XXXXXXXX under Gossaigaon PS, Dist- Kokrajhar, Assam. 10 Details of Properties XXXXXXXXXX /Articles/ Documents seized during the investigation & relied upon 11.1 Particulars of accused person charge sheeted: A-2 Name (A-2) Rabi Basumatary @ B. Rongjabaja @ Rabi Whether verified Yes Father‟s Name S/o- Late Gorgo Basumutary, Year/Date of Birth 30 years old at the time of arrest. Sex Male Nationality Indian Passport No. NA Place of issue NA Date of issue NA Religion Christian Occupation A member of NDFB CHARGE SHEET: NIA CASE NO. -

Nediv Ndfbfinalorder 180820

UNLAWFUL ACTIVITIES (PREVENTION) TRIBUNAL AAI BUILDING, MAGISTRATE'S COLONY, HADAYTPUR. GUWAHATI ll n al, E I4ATTER OF TNATIONAL DEMOCRATIC FRONT OF BODOLAND (NDF8) @? d$ BEFORE HON'BLE MR JUSTICE PRASANTA KUMAR DEKA Presiding Officer For the State of Assam Mr. D Saikia. S€nior Advocate [4r. P. Nayak, Advocate Mr. A. Chaliha, Advocate. For the Union of India l4r. S. C. Keyal, Assistant Solicitor General of India. For the NDFB (RD) & NDFB(Dhirendra Boro croup) Ms. N. Daimari, Advocate. For the NDFB (S) Group Mr. A. Nazari, Advocate. Date of hearing/argument 01.08.2020 Date of adjudication 18.08.2020 ORDER l. On 23'd November, 2019, a Notification being S.O. 4255(E) was issued by I4r. Satyendra Garg, loint Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India to the effect that the Central Government was of the opinion that the adivities of the National Democratic Front of Bodoland (hereinafter referred to as NDFB) were detrimental to the sovereignty and integrity of India and that it is an unlaMul association. 2. The Central Government was also of the opinion that if there is no immediate curb and control of the unlawful activities of NDFB, the organization may re-group and re-arm itself, make fresh recruitments, indulqe in violent, terrorist and secessionist F, activities, collect funds and endanger the lives of innocent citizens and security forces personnel and therefore exasting circumstances rendered it necessary to declare the Presldtng Officer UnlarvlulActivities (prelnnr onl Triburrt in The tValter ot iiDrii PaBe 1 of 75 NDFB, along wath all its groups, factions and front organizations as an unlawful association with immediate effect. -

Notice Tezpur University

NOTICE Dated 19 / 08 / 2019 TEZPUR UNIVERSITY Screening Test for shortlisting of Applicants for Skill Test for the positions of UPPER DIVISION CLERK against Advertisement No. 01/2019 dated 08-02-2019 Date of Test : 07 September, 2019 (Saturday) Venue : Deans’ Building, School of Engineering, Tezpur University Time : 10 a.m. to 12 noon. (Reporting Time: 09.45 a.m.) Details of Screening Test and Instruction to Candidates: Following shall be the plan of the Screening Test, its components and syllabus etc. for screening of candidates for appearing in the Skill Test for the positions of UPPER DIVISION CLERK of Tezpur University. Components of Written Test Test Components – Total 100 marks Time Remarks Objective Type (Multiple Choice) Test 2 hours 1. The questions shall generally be on the Part A- General Awareness –25 marks minimum qualification level. Part B – General Intelligence and Reasoning – 25 marks 2. Each question will carry 1 mark. Part C - Numerical Aptitude -- 25 marks Part D – General English – 25 marks 3. There shall be negative mark of 0.25 for each wrong answer. Detailed Syllabus Part A- General Awareness: Questions will be designed to test the ability of the candidate’s general awareness of the environment around him/her and its application to society. Questions will also be designed to test knowledge of current events and of such matters of everyday observation and experience in their scientific aspects as may be expected of an educated person. The test will also include questions relating to India and north eastern states especially pertaining to Sports, History, Culture, Geography, Economic scene, General Polity including Indian Constitution, and Scientific Research etc. -

Wildlife of the Brahmaputra

WILDLIFE OF THE BRAHMAPUTRA Kashmira Kakati “The native town of Gowahatty is built entirely of bamboos, reeds, and grass. To the south an extensive marsh almost surround the whole station, and the contiguity of many old tanks, choked with jungle, coupled with the vicinity of the hills on every quarter except the north, renders this town, in spite of the improvements already alluded to, one of the most insalubrious in Assam’. “I arrived at the mouth of the little stream Dikhoo, and mounting an elephant, rode through a dense tree and grass jungle to Seebsaugur, distant twelve miles from the Burrampooter”. “In the Chawlkhowa river, opposite Burpetah, I have seen basking in the sun on the sand banks, as many as ten crocodiles at a time; and upon one occasion, a heap of a hundred crocodiles’s eggs, each about the size of a turkey’s egg, were discovered on a sand bank, and brought to me”. - From ‘A Sketch of Assam’, John Butler, 1847 Photo on previous age: A makhna at Poba Reserve Forest, the last rainforest remnant flush on the Brahmaputra. 2 CONTENTS Acknowledgment ...4 Summary...7 Introduction...8 Objectives & Methods...10 Site/Species Accounts...17 1. D’ering Wildlife Sanctuary, Arunachal Pradesh...17 2. Kobo Chapori & Poba Reserve Forest...20 3. Dibru-Saikhowa National park and Motapung-Maguri Beels...25 4. The River Elephants...29 5. Panidehing WLS & Dikhowmukh...41 6. Molai Chapori...44 7. Bordoibam-Bilmukh Proposed Bird Sanctuary...48 8. Satjan Wetland & Ranganadi and Subansiri Dams...50 9. River Dolphins – by Abdul Wakid...53 10. -

Sonitpur District, Assam

कᴂद्रीय भूमि जल बो셍ड जल संसाधन, नदी विकास और गंगा संरक्षण विभाग, जल शक्ति मंत्रालय भारत सरकार Central Ground Water Board Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation, Ministry of Jal Shakti Government of India AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT OF GROUND WATER RESOURCES SONITPUR DISTRICT, ASSAM उत्तर पूिी क्षेत्र, गुिाहाटी North Eastern Region, Guwahati FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Technical series D No……../2019-20 Central Ground Water Board कᴂद्रीय भूजल बो셍ड MINISTRY OF JAL SHAKTI जल शक्ति मंत्रालय Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation जल संसाधन,नदी क्तिकास और गंगा संरक्षण क्तिभाग GOVERNMENT OF INDIA भारत सरकार REPORT ON AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT IN SONITPUR DISTRICT, ASSAM ANNUAL ACTION PLAN, 2018-19 NORTH EASTERN REGION उत्तर पूर्वीक्षेत्र GUWAHATI गुर्वाहाटी December 2020 AQUIFER MAPPING IN SONITPUR DISTRICT, ASSAM REPORT ON AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT IN SONITPUR DISTRICT, ASSAM ANNUAL ACTION PLAN, 2018-19 By Dr. D. J. Khound, Asst. Hydrogeologist & Wanjano Mozhui Scientist-B Central Ground Water Board North Eastern Region Guwahati 2 AQUIFER MAPPING IN SONITPUR DISTRICT, ASSAM CONTENTS CHAPTER 1.0 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Objectives 1 1.2 Scope of the study 1 1.3. Approach and methodology 1 1.4 Area Details 1 1.5 Data availability, data adequacy, data gap analysis and data generation 3 1.6 Rainfall-spatial, temporal and secular distribution 5 1.7 Physiographic set up 5 1.8 Geomorphology 6 1.9 Land use Pattern 8 1.10 Soil 9 1.11 Hydrology and surface water 10 1.12 Agriculture 11 1.13 Industry: 13 CHAPTER 2.0 14 DATA COLLECTION AND GENERATION 14 2.1 Data collection 14 2.1.1 Hydrogeological data 14 2.1.2 Exploration data 14 2.1.3 Meterological Data 14 2.1.3 Population and agriculture data 14 2.2. -

IEE: India: Assam Power Sector Enhancement Investment Program

Initial Environment Examination Project Number: 41614-035 July 2017 IND: Assam Power Sector Enhancement Investment Program - Tranche 3 Submitted by Assam Power Distribution Company Limited, Guwahati This report has been submitted to ADB by the Assam Power Distribution Company Limited, Guwahati and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s Public Communications Policy (2011). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. This report is an updated version of the IEE report posted in August 2011 available on https://www.adb.org/projects/docu ments/assam-power-sector-enhancement-investment- program-tranche-3-0. This updated initial environment examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Updated Initial Environmental Examination June 2017 India: Assam Power Sector Enhancement Investment Program – Tranche 3 Prepared by Assam State Electricity Board for the Asian Development Bank The initial environmental examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary -

Insurgency in Assam

Chapter 1 INSURGENCY IN ASSAM The state of Assam has been under the grip of insurgency for more than three decades. Located in the strategic northeastern corner of India, it is part of a region which shares a highly porous and sensitive frontier with China in the North, Myanmar in the East, Bangladesh in the Southwest and Bhutan to the Northwest. Spread over 2,62,179 sq. km1, the strategic importance of Northeast India can be determined from the fact that it shares a 4,500 km-long international border with four South Asian neighbours but is connected to the Indian mainland by only a tenuous 22 km-long land corridor passing through Siliguri in the eastern state of West Bengal, fancifully described as the ‗Chicken‘s Neck.‘ The northeastern region is also an ethnic minefield, as it comprises of around 160 Scheduled Tribes, besides an estimated 400 other tribal or sub-tribal communities and groups.2 Turbulence in India‘s Northeast is, therefore, not caused just by armed separatist groups representing different ethnic communities fighting the central or the local governments or their symbols to press for either total independence or autonomy, but also by the recurring battles for territorial supremacy among the different ethnic groups themselves. Being part of such a region, the state of Assam has also had its share of insurgency movements, which are yet to completely die down. Insurgency began in Assam with the birth of the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA) in 1979. On 7 April 1979, six radical Assamese youths met at the Rang Ghar, the famous amphitheatre of the Ahom royalty (the Ahoms ruled Assam for 600 years, beginning 1228 AD) and formed the ULFA, vowing to fight against the ―colonial Indian Government‖ with the ultimate aim to achieve a ―sovereign, socialist Assam‖.