GREEN-TAILED TOWHEE Pipilo Chlorurus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildlife of the North Hills: Birds, Animals, Butterflies

Wildlife of the North Hills: Birds, Animals, Butterflies Oakland, California 2005 About this Booklet The idea for this booklet grew out of a suggestion from Anne Seasons, President of the North Hills Phoenix Association, that I compile pictures of local birds in a form that could be made available to residents of the north hills. I expanded on that idea to include other local wildlife. For purposes of this booklet, the “North Hills” is defined as that area on the Berkeley/Oakland border bounded by Claremont Avenue on the north, Tunnel Road on the south, Grizzly Peak Blvd. on the east, and Domingo Avenue on the west. The species shown here are observed, heard or tracked with some regularity in this area. The lists are not a complete record of species found: more than 50 additional bird species have been observed here, smaller rodents were included without visual verification, and the compiler lacks the training to identify reptiles, bats or additional butterflies. We would like to include additional species: advice from local experts is welcome and will speed the process. A few of the species listed fall into the category of pests; but most - whether resident or visitor - are desirable additions to the neighborhood. We hope you will enjoy using this booklet to identify the wildlife you see around you. Kay Loughman November 2005 2 Contents Birds Turkey Vulture Bewick’s Wren Red-tailed Hawk Wrentit American Kestrel Ruby-crowned Kinglet California Quail American Robin Mourning Dove Hermit thrush Rock Pigeon Northern Mockingbird Band-tailed -

Bird Species Checklist

6 7 8 1 COMMON NAME Sp Su Fa Wi COMMON NAME Sp Su Fa Wi Bank Swallow R White-throated Sparrow R R R Bird Species Barn Swallow C C U O Vesper Sparrow O O Cliff Swallow R R R Savannah Sparrow C C U Song Sparrow C C C C Checklist Chickadees, Nuthataches, Wrens Lincoln’s Sparrow R U R Black-capped Chickadee C C C C Swamp Sparrow O O O Chestnut-backed Chickadee O O O Spotted Towhee C C C C Bushtit C C C C Black-headed Grosbeak C C R Red-breasted Nuthatch C C C C Lazuli Bunting C C R White-breasted Nuthatch U U U U Blackbirds, Meadowlarks, Orioles Brown Creeper U U U U Yellow-headed Blackbird R R O House Wren U U R Western Meadowlark R O R Pacific Wren R R R Bullock’s Oriole U U Marsh Wren R R R U Red-winged Blackbird C C U U Bewick’s Wren C C C C Brown-headed Cowbird C C O Kinglets, Thrushes, Brewer’s Blackbird R R R R Starlings, Waxwings Finches, Old World Sparrows Golden-crowned Kinglet R R R Evening Grosbeak R R R Ruby-crowned Kinglet U R U Common Yellowthroat House Finch C C C C Photo by Dan Pancamo, Wikimedia Commons Western Bluebird O O O Purple Finch U U O R Swainson’s Thrush U C U Red Crossbill O O O O Hermit Thrush R R To Coast Jackson Bottom is 6 Miles South of Exit 57. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Song Variations and Singing Behavior in the Rufous-Sided Towhee, Pipilo Erythrophthalmus Oregonus

SONG VARIATIONS AND SINGING BEHAVIOR IN THE RUFOUS-SIDED TOWHEE, PlPlLO ERYTHROPHTHALMUS OREGONUS \ DONALD E. KROODSMA Department of Zoology Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon 97331 The singing behavior and vocalizations of the total song length. To the human ear this in- Rufous-sided Towhee ( Pipilo erythrophthal- troductory phrase was often inaudible and the mus) have been described recently by several song appeared to consist of a trill alone. authors (e.g., Davis 1958; Borror 1959; Roberts Each sonagram in figure 2 represents a song 1969). All have recognized variation in the type, i.e., one of the distinctive songs repeated song repertoire of both individuals and popu- in a consistent manner in the repertoire of an lations, yet only the variation in songs sampled individual. The male towhees sang a given from the eastern subspecies (Borror 1959) has song type at the rate of 8-15 songs per min for received extensive sonagraphic analysis. Here up to 15 min; at times, however, especially I discuss 1) the song variations observed in during early morning, males alternated two the repertoires of four neighboring males of song types, singing first one and then the other the race 2.’ e. oregonus, 2) the similarities of in sequence for several minutes at a time. Re- variations among these birds, and 3) the use gardless of the pattern of singing behavior, in of variations in the singing behavior of the successive renditions of a song type the struc- individual. ture of the introductory phrase and the trill syllables were unaltered; only the number of METHODS syllables in the trill varied. -

A WHITE-EYED SPOTTED TOWHEE OBSERVED in NORTHWESTERN NEBRASKA RICK WRIGHT, 128 Evans Road, Bloomfield, New Jersey 07003; [email protected]

NOTES A WHITE-EYED SPOTTED TOWHEE OBSERVED IN NORTHWESTERN NEBRASKA RICK WRIGHT, 128 Evans Road, Bloomfield, New Jersey 07003; [email protected] Towhees visually—and in rare cases vocally—resembling the Eastern Towhee (Pipilo erythrophthalmus) have been reported at least eight times this century in the Nebraska Panhandle (Silcock and Jorgensen 2018), far to the west of that taxon’s expected range. As a result of the resplitting of the Eastern Towhee and Spotted Towhee (P. maculatus) (AOU 1995), observers have begun to once again pay close attention to the appearance and vocalizations of the region’s towhees, a practice that had declined following the species’ earlier taxonomic lumping (AOU 1954). On 20 and 21 May 2018, I observed a Spotted Towhee (presumptively P. m. arcticus, which breeds in the area) with white irides in the campground at the Gilbert- Baker Wildlife Area (42° 46.02' N, 103° 55.67' W) in the extreme northwest of the Nebraska Panhandle, 10 km north of Harrison, Sioux County. I photographed the bird on the first date (Figure 1). The deep saturated black of the head indicated that this individual was a male; the browner primaries were presumably retained juvenile feathers, contrasting with the rest of the formative plumage, identifying this as an individual in its second calendar year. When I returned on the second date, the towhee was accompanied by a female Spotted Towhee of unknown age; her plumage and soft-part colors were unremarkable. Silent the day before, on this occasion the male sang several times, a series of loud ticking notes followed by a lower-pitched, buzzy trill indistinguishable to my ear from the vocalizations of other nearby Spotted Towhees. -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below. -

Song Variations and Singing Behavior in the Rufous-Sided Towhee, Pipilo Erythrophthalmus Oregonus

SONG VARIATIONS AND SINGING BEHAVIOR IN THE RUFOUS-SIDED TOWHEE, PlPlLO ERYTHROPHTHALMUS OREGONUS \ DONALD E. KROODSMA Department of Zoology Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon 97331 The singing behavior and vocalizations of the total song length. To the human ear this in- Rufous-sided Towhee ( Pipilo erythrophthal- troductory phrase was often inaudible and the mus) have been described recently by several song appeared to consist of a trill alone. authors (e.g., Davis 1958; Borror 1959; Roberts Each sonagram in figure 2 represents a song 1969). All have recognized variation in the type, i.e., one of the distinctive songs repeated song repertoire of both individuals and popu- in a consistent manner in the repertoire of an lations, yet only the variation in songs sampled individual. The male towhees sang a given from the eastern subspecies (Borror 1959) has song type at the rate of 8-15 songs per min for received extensive sonagraphic analysis. Here up to 15 min; at times, however, especially I discuss 1) the song variations observed in during early morning, males alternated two the repertoires of four neighboring males of song types, singing first one and then the other the race 2.’ e. oregonus, 2) the similarities of in sequence for several minutes at a time. Re- variations among these birds, and 3) the use gardless of the pattern of singing behavior, in of variations in the singing behavior of the successive renditions of a song type the struc- individual. ture of the introductory phrase and the trill syllables were unaltered; only the number of METHODS syllables in the trill varied. -

California Bird Species of Special Concern

California Bird Species of Special Concern A Ranked Assessment of Species, Subspecies, and Distinct Populations of Birds of Immediate Conservation Concern in California W. DAVID SHUFORD AND THOMAS GARDALI, EDITORS WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE PROJECT MANAGER Lyann A. Comrack IN COLLABORATION WITH THE BIRD SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN TECHNICAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE Edward C. Beedy, Bruce E. Deuel, Richard A. Erickson, Sam D. Fitton, Kimball L. Garrett, Kevin Hunting, Tim Manolis, Michael A. Patten, W. David Shuford, John Sterling, Philip Unitt, Brian J. Walton Studies of Western Birds No. 1 Published by Western Field Ornithologists Camarillo, California and California Department of Fish and Game Sacramento, California WITH SUPPORT FROM Audubon California, BonTerra Consulting, EDAW, H. T. Harvey & Associates, Jones & Stokes, LSA Associates, The Nature Conservancy, PRBO Conservation Science, SWCA Environmental Consultants Studies of Western Birds No. 1 Studies of Western Birds, a monograph series of Western Field Ornithologists, publishes original scholarly contributions to field ornithology from both professionals and amateurs that are too long for inclusion in Western Birds. The region of interest is the Rocky Mountain and Pacific states and provinces, including Alaska and Hawaii, western Texas, northwestern Mexico, and the northeastern Pacific Ocean. Subject matter may include studies of distribution and abundance, population dynamics, other aspects of ecology, geographic variation, systematics, life history, migration, behavior, and conservation. Submit manuscripts to the editor, Kenneth P. Able, Bob’s Creek Ranch, 535-000 Little Valley Rd., McArthur, CA 96056; we highly recommend discussing potential submissions with the editor prior to manuscript preparation (email: [email protected]). Studies of Western Birds No. -

Eccentric Preformative Molt in the Spotted Towhee Stephen M

NOTES ECCENTRIC PREFORMATIVE MOLT IN THE SPOTTED TOWHEE STEPHEN M. FETTIG, Migratory Bird Program, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2800 Cottage Way, Sacramento, California 95825; [email protected] CHARLES D. HATHCOCK, Los Alamos National Laboratory, P. O. Box 1663, Los Alamos, New Mexico 87545; [email protected] Examination of wing-feather molt often provides information essential for aging birds in the hand (Mulvihill 1993, Pyle 1997b, 2008). Correctly aging birds is important for understanding the causal relationships between age-class survival rates and population changes (DeSante et al. 2005). For example, correctly aging birds facilitates understanding of climate effects on reproduction better than merely moni- toring population numbers because reproduction varies widely with annual weather patterns (DeSante and O’Grady 2000). Age-class information can also provide a clear measure of habitat quality without confounding effects such as population sources and sinks (Van Horne 1983) or misleading habitat-quality information based on relative abundance or population size (Pulliam 1988). Changes in bird populations often lag changes in the survival rate of an age class, while environmental changes often affect one age class immediately or after a short lag (Temple and Wiens 1989). Greenlaw (1996) reported that the preformative molt of the Spotted Towhee (Pipilo maculatus) consists of the replacement of body feathers, tail feathers, and secondary coverts while the remiges and primary coverts of the juvenile plumage are retained. In addition, Byers et al. (1997), writing about the Rufous-sided Towhee before its split into the Eastern Towhee (P. erythrophthalmus) and Spotted Towhee, reported the preformative molt also includes some or all of the rectrices. -

Worcester County Birdlist

BIRD LIST OF WORCESTER COUNTY, MASSACUSETTS 1931-2019 This list is a revised version of Robert C. Bradbury’s Bird List of Worcester County, Massachusetts (1992) . It contains bird species recorded in Worcester County since the Forbush Bird Club began publishing The Chickadee in 1931. Included in Appendix A, and indicated in bold face on the Master List are bird Species which have been accepted by the Editorial Committee of The Chickadee, and have occurred 10 times or fewer overall, or have appeared fewer than 5 times in the last 20 years in Worcester County. The Editorial Committee has established the following qualifying criteria for any records to be considered of any record not accepted on the Master List: 1) a recognizable specimen 2) a recognizable photograph or video 3) a sight record corroborated by 3 experienced observers In addition, any Review Species with at least one accepted record must pass review of the Editorial Committee of the Chicka dee. Any problematic records which pass review by the Chickadee Editorial Committee, but not meeting the three first record rules above, will be carried into the accepted records of the given species. Included in Appendix B are records considered problematic. Problematic species either do not meet at least one of the qualifying criteria listed above, are considered likely escaped captive birds, have arrived in Worcester County by other than self-powered means, or are species not yet recognized as a count able species by the Editorial Committee of The Chickadee . Species names in English and Latin follow the American Ornithologists’ Union Checklist of North American Birds, 7 th edition, 59th supplement, rev. -

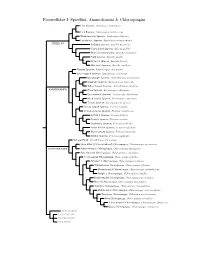

Passerellidae Species Tree

Passerellidae I: Spizellini, Ammodramini & Chlorospingini Lark Sparrow, Chondestes grammacus Lark Bunting, Calamospiza melanocorys Black-throated Sparrow, Amphispiza bilineata Five-striped Sparrow, Amphispiza quinquestriata SPIZELLINI Chipping Sparrow, Spizella passerina Clay-colored Sparrow, Spizella pallida Black-chinned Sparrow, Spizella atrogularis Field Sparrow, Spizella pusilla Brewer’s Sparrow, Spizella breweri Worthen’s Sparrow, Spizella wortheni Tumbes Sparrow, Rhynchospiza stolzmanni Stripe-capped Sparrow, Rhynchospiza strigiceps Grasshopper Sparrow, Ammodramus savannarum Grassland Sparrow, Ammodramus humeralis Yellow-browed Sparrow, Ammodramus aurifrons AMMODRAMINI Olive Sparrow, Arremonops rufivirgatus Green-backed Sparrow, Arremonops chloronotus Black-striped Sparrow, Arremonops conirostris Tocuyo Sparrow, Arremonops tocuyensis Rufous-winged Sparrow, Peucaea carpalis Cinnamon-tailed Sparrow, Peucaea sumichrasti Botteri’s Sparrow, Peucaea botterii Cassin’s Sparrow, Peucaea cassinii Bachman’s Sparrow, Peucaea aestivalis Stripe-headed Sparrow, Peucaea ruficauda Black-chested Sparrow, Peucaea humeralis Bridled Sparrow, Peucaea mystacalis Tanager Finch, Oreothraupis arremonops Short-billed (Yellow-whiskered) Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus parvirostris CHLOROSPINGINI Yellow-throated Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus flavigularis Ashy-throated Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus canigularis Sooty-capped Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus pileatus Wetmore’s Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus wetmorei White-fronted Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus albifrons Brown-headed -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and