FOR US by US: Explorations and Introspections on the Poetics of Black Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017 Researched, compiled, and calculated by Lance Mangham Contents • Sources • The Top 100 of All-Time • The Top 100 of Each Year (2017-1956) • The Top 50 of 1955 • The Top 40 of 1954 • The Top 20 of Each Year (1953-1930) • The Top 10 of Each Year (1929-1900) SOURCES FOR YEARLY RANKINGS iHeart Radio Top 50 2018 AT 40 (Vince revision) 1989-1970 Billboard AC 2018 Record World/Music Vendor Billboard Adult Pop Songs 2018 (Barry Kowal) 1981-1955 AT 40 (Barry Kowal) 2018-2009 WABC 1981-1961 Hits 1 2018-2017 Randy Price (Billboard/Cashbox) 1979-1970 Billboard Pop Songs 2018-2008 Ranking the 70s 1979-1970 Billboard Radio Songs 2018-2006 Record World 1979-1970 Mediabase Hot AC 2018-2006 Billboard Top 40 (Barry Kowal) 1969-1955 Mediabase AC 2018-2006 Ranking the 60s 1969-1960 Pop Radio Top 20 HAC 2018-2005 Great American Songbook 1969-1968, Mediabase Top 40 2018-2000 1961-1940 American Top 40 2018-1998 The Elvis Era 1963-1956 Rock On The Net 2018-1980 Gilbert & Theroux 1963-1956 Pop Radio Top 20 2018-1941 Hit Parade 1955-1954 Mediabase Powerplay 2017-2016 Billboard Disc Jockey 1953-1950, Apple Top Selling Songs 2017-2016 1948-1947 Mediabase Big Picture 2017-2015 Billboard Jukebox 1953-1949 Radio & Records (Barry Kowal) 2008-1974 Billboard Sales 1953-1946 TSort 2008-1900 Cashbox (Barry Kowal) 1953-1945 Radio & Records CHR/T40/Pop 2007-2001, Hit Parade (Barry Kowal) 1953-1935 1995-1974 Billboard Disc Jockey (BK) 1949, Radio & Records Hot AC 2005-1996 1946-1945 Radio & Records AC 2005-1996 Billboard Jukebox -

Sixty Years at Purchase MANHATTANVILLE the Magazine of Manhattanville College

Manhattanville THE MAGAZINE OF MANHATTANVILLE COLLEGE | SPRING 2013 www.manhattanville.edu 1952–2012: Sixty Years At Purchase MANHATTANVILLE The Magazine of Manhattanville College Jon C. Strauss, Ph.D. President Manhattanville College Jose R. Gonzalez Vice President Office of Institutional Advancement Teresa S. Weber Assistant Vice President Office of Institutional Advancement J.J. Pryor Managing Director Office of Communications Tun N. Aung Director Brand Management and Creative Services Office of Communications CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Aarushi Bhandari ’13 Communications Assistant Jennifer Griffin ’07 Assistant Director, Alumni Relations Elizabeth Baldini ’09 Alumni Relations Officer Steve Sheridan Director Sports Information, Athletics Caren Wagner-Roth, MAW ’01 Casey Tolfree PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS Candice Alcantara ’14 Photography Intern Stephanie Camerone ’14 Communications Assistant Nicole Pupora ’15 Photography Intern Manhattanville College is committed to equality of educational opportunity, and is an equal opportunity employer. The College does not discriminate against current or prospective students and employees on the basis of race, color, sex, national and ethnic origin, religion, age, disability, or any other legally protected characteristic. This College policy is implemented in educational and admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, athletic and other school-administered programs, and in employee-related programs. Manhattanville Magazine is published annually by Manhattanville College, 2900 Purchase Street, Purchase, -

President's Corner

Subscribe Past Issues Translate RSS President's Corner Dear Friends and Members, Greetings for this start of February 2021 and continued hope that safety and health are at the top of everyone’s agenda. The CCC anticipates a very productive year of presentation and information. Our next scheduled webinar is set for February 9th and is entitled “Music Influencing Sports and Sports Influencing Music.” Given the webinar’s proximity to the Superbowl, the discussion is particularly timely and apropos. CCC Board Member, Carolyn Soyars is moderating this discussion of the very real connection and symbiosis between sports and music, and the impact the pandemic has had on the nature of that relationship. The participating panelists bring a wealth of knowledge and expertise in this arena, and can really knock it out of the park. Thank you to all who participated in our Raffle and Auction effort on behalf of the John Braheny CCC Scholarship that took place last month and congratulations to all the lucky winners. We would also like to recognize the efforts of our terrific Scholarship Committee under the able chairmanship of Reggie Calloway. Members, once again, please note that our webinars for June, September, October, November, December, January are now available for viewing on our website. If you happened to have missed a prior webinar, take advantage of this benefit of membership. Thank you for your continued support of the CCC and follow us on various platforms of social media. Sincerely, Garrett M. Johnson, Esq. CCC President 2020–2021 CCC WEBINAR SERIES: Tuesday, February 9th, 2021 2:30pm PST - 3:30pm PST “MUSIC INFLUENCING SPORTS AND SPORTS INFLUENCING MUSIC” A panel of music curators, composers, and licensees will be hitting a grand slam to de-mystify these areas… How music is licensed and used in sports The connections between music and sports New ways sports and music have been collaborating Where music plays into broadcast programming and has created new opportunities Plus, the sticky wicket changes the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the sports world. -

12-04 Show Date: Weekend of January 21-22, 2012 Disc One/Hour One Opening Billboard: None Seg

Show Code: #12-04 Show Date: Weekend of January 21-22, 2012 Disc One/Hour One Opening Billboard: None Seg. 1 Content: #40 “T.H.E. (THE HARDEST EVER)” – will.i.am f/Mick Jagger & Jennifer Lopez #39 “MUSIC SOUNDS BETTER WITH U” – Big Time Rush f/Mann #38 “JUST A KISS” – Lady Antebellum Commercials: :30 ONDCP/Teen Paid :30 Intuit / Turbo :30 Clorox Home Care :30 Digiorno Outcue: “...gonna be awesome.” Segment Time: 14:53 Local Break 2:00 Seg. 2 Content: #37 “YOUNG, WILD & FREE” – Wiz Khalifa & Snoop Dogg f/Bruno Mars #36 “WISH YOU WERE HERE” – Avril Lavigne #35 “I WANNA GO” – Britney Spears #34 “IT GIRL” – Jason Derülo Commercials: :30 Subway/Fresh :30 H&R Block/1040E :30 Toyota/Prius :30 Progressive Insurance Outcue: “...in all states.” Segment Time: 17:04 Local Break 2:00 Seg. 3 Content: #33 “HEARTBEAT” – The Fray #32 “TURN ME ON” – David Guetta f/Nicki Minaj #31 “SELF BACK HOME” – Gym Class Heroes f/Neon Hitch Break Out: “DANCE” – Big Sean Commercials: :30 Proactiv :30 Green Mountain Outcue: “...single serve brewers.” Segment Time: 16:26 Local Break 1:00 Seg. 4 ***This is an optional cut - Stations can opt to drop song for local inventory*** Content: AT40 Extra: “TOO LITTLE TOO LATE” – Jojo Outcue: “…AT40 mobile app.” (sfx) Segment Time: 3:48 Hour 1 Total Time: 57:11 END OF DISC ONE Show Code: #12-04 Show Date: Weekend of January 21-22, 2012 Disc Two/Hour Two Opening Billboard None Seg. 1 Content: #30 “INTERNATIONAL LOVE” – Pitbull f/Chris Brown #29 “TONIGHT IS THE NIGHT” – Outasight #28 “SUPER BASS” – Nicki Minaj Extra: “ROLLING IN THE DEEP” – Adele Commercials: :30 Subway/Fresh :30 Intuit / Turbo :60 California Psychics Outcue: “...experienced, it’s free.” Segment Time: 17:18 Local Break 2:00 Seg. -

WOW Hall Notes 2013-02.Indd

FEBRUARY 2013 WOW HALL NOTES g VOL. 25 #2 ★ WOWHALL.ORG Club Bellydance Bellydance Superstars On BDSS tours, we rarely have Productions’ new club-style tour time for our dancers to see how Club Bellydance is touring North Bellydance is advancing across the America and will be making a stop USA and Canada. This led to an at the WOW Hall on Tuesday, idea to create a shorter and smaller February 26! Bellydance Superstars show that Club Bellydance is a two- teams up with dance teachers and act performance concept that troupes in each city. and put on features select dancers from a combined show celebrating the the internationally renowned state of this art in North America Bellydance Superstars and locally- today. based premier bellydancers. Each local Bellydance Bellydance Superstars’ Sabah, community provides the fi rst half Moria, Sabrina, Victoria and of the show and the BDSS dancers Nathalie will showcase new the second half. We call it Club choreography and ideas designed Bellydance. for the intimate, club-style show. MEET THE DANCERS ballet and bellydance was added fusion isolation and individualism. just to name a few. Sabrina is also WHAT IS CLUB BELLYDANCE? Victoria Teel is an award to the show as a special feature. Moria has appeared in several certifi ed in and has been teaching After eight years of traveling the winning performer and instructor. Sabah began her professional Bellydance Superstars performance Vinyasa Flow yoga for 5 years. world as the Bellydance Superstars Beginning in 2006, she studied career performing in numerous DVDs - 30 Days to Vegas, Nathalie is a professional — over 800 shows in 23 countries — multiple dance styles including productions of The Nutcracker for Babelesque: Live from Tokyo, actress, dancer, choreographer and watching this dance art grow as Egyptian, Turkish, American 12 years. -

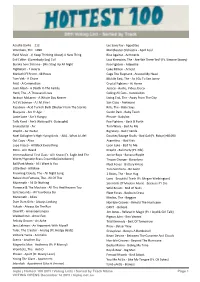

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Track Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

Azealia Banks - 212 Les Savy Fav - Appetites Wombats, The - 1996 Manchester Orchestra - April Fool Field Music - (I Keep Thinking About) A New Thing Rise Against - Architects Evil Eddie - (Somebody Say) Evil Last Kinection, The - Are We There Yet? {Ft. Simone Stacey} Buraka Som Sistema - (We Stay) Up All Night Foo Fighters - Arlandria Digitalism - 2 Hearts Luke Million - Arnold Mariachi El Bronx - 48 Roses Cage The Elephant - Around My Head Tom Vek - A Chore Middle East, The - As I Go To See Janey Feist - A Commotion Crystal Fighters - At Home Juan Alban - A Death In The Family Justice - Audio, Video, Disco Herd, The - A Thousand Lives Calling All Cars - Autobiotics Jackson McLaren - A Whole Day Nearer Living End, The - Away From The City Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! San Cisco - Awkward Kasabian - Acid Turkish Bath (Shelter From The Storm) Kills, The - Baby Says Bluejuice - Act Yr Age Caitlin Park - Baby Teeth Lanie Lane - Ain't Hungry Phrase - Babylon Talib Kweli - Ain't Waiting {Ft. Outasight} Foo Fighters - Back & Forth Snakadaktal - Air Tom Waits - Bad As Me Drapht - Air Guitar Big Scary - Bad Friends Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds - AKA…What A Life! Douster/Savage Skulls - Bad Gal {Ft. Robyn}+B1090 Cut Copy - Alisa Argentina - Bad Kids Lupe Fiasco - All Black Everything Loon Lake - Bad To Me Mitzi - All I Heard Drapht - Bali Party {Ft. Nfa} Intermashional First Class - All I Know {Ft. Eagle And The Junior Boys - Banana Ripple Worm/Hypnotic Brass Ensemble/Juiceboxxx} Tinpan Orange - Barcelona Ball Park Music - All I Want Is You Fleet Foxes - Battery Kinzie Little Red - All Mine Tara Simmons - Be Gone Frowning Clouds, The - All Night Long 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Naked And Famous, The - All Of This Lanu - Beautiful Trash {Ft. -

Artist Song Album Blue Collar Down to the Line Four Wheel Drive

Artist Song Album (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Blue Collar Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Down To The Line Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Four Wheel Drive Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Free Wheelin' Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Gimme Your Money Please Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Hey You Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Let It Ride Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Lookin' Out For #1 Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Roll On Down The Highway Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Take It Like A Man Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Hits of 1974 (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothin' Yet Hits of 1974 (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. Blue Sky Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Rockaria Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Showdown Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Strange Magic Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Sweet Talkin' Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Telephone Line Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Turn To Stone Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. -

DJ Song List by Song

A Case of You Joni Mitchell A Country Boy Can Survive Hank Williams, Jr. A Dios le Pido Juanes A Little Bit Me, a Little Bit You The Monkees A Little Party Never Killed Nobody (All We Got) Fergie, Q-Tip & GoonRock A Love Bizarre Sheila E. A Picture of Me (Without You) George Jones A Taste of Honey Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass A Ti Lo Que Te Duele La Senorita Dayana A Walk In the Forest Brian Crain A*s Like That Eminem A.M. Radio Everclear Aaron's Party (Come Get It) Aaron Carter ABC Jackson 5 Abilene George Hamilton IV About A Girl Nirvana About Last Night Vitamin C About Us Brook Hogan Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Abracadabra Sugar Ray Abraham, Martin and John Dillon Abriendo Caminos Diego Torres Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Nine Days Absolutely Not Deborah Cox Absynthe The Gits Accept My Sacrifice Suicidal Tendencies Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Ace In The Hole George Strait Ace Of Hearts Alan Jackson Achilles Last Stand Led Zeppelin Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Across The Lines Tracy Chapman Across the Universe The Beatles Across the Universe Fiona Apple Action [12" Version] Orange Krush Adams Family Theme The Hit Crew Adam's Song Blink-182 Add It Up Violent Femmes Addicted Ace Young Addicted Kelly Clarkson Addicted Saving Abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted Sisqó Addicted (Sultan & Ned Shepard Remix) [feat. Hadley] Serge Devant Addicted To Love Robert Palmer Addicted To You Avicii Adhesive Stone Temple Pilots Adia Sarah McLachlan Adíos Muchachos New 101 Strings Orchestra Adore Prince Adore You Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel -

Diversity Guide – Northern Plains Region

G.R.A.C.E. Guide to Resources for Annual Campus Events Diversity Guide – Northern Plains Region NACA® Statement on Diversity Diversity is an attribute and a goal. As an attribute, diversity is ethnic identification/race, gender identity, disability, sexual orientation, age, religion, economic status and the many other aspects of our lives which define the family of humanity. As a goal, diversity refers to the intentional valuing, respecting and inclusion of all peoples. NACA recognizes the diversity of all its members and supports the development and implementation of programs and services that achieve this goal. Diversity Initiatives Collaboration In support of NACA’s Statement on Diversity, the Diversity Initiatives Coordinators for all regions collaborated to produce Diversity Guides in each region that highlight diversity programs and activities offered by associate members who are exhibiting at the various regional conferences. This guide is modeled after previous efforts by Diversity Initiatives Coordinators in the Mid Atlantic and Northern Plains regions. All conference delegates who have an interest in bringing diversity programs to their campuses are encouraged to review the programs listed in the guide prior to attending the conference and then to visit the agencies in the Campus Activities Marketplace (CAMP). Each program listed provides the name of the agency, booth location, contact information, price range, and a brief overview of the program. As a convenience while at the conference, delegates may also access this information -

RHAPSODY Thank You for Joining Us at Our Showcase This Evening

PRESENTS… RHAPSODY Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, you’ll be viewing the band Rhapsody, led by Charlie D’Oria and Greg Warno. Rhapsody has been performing successfully in the wedding industry for over 20 years. Their experience and professionalism will ensure a great party and a memorable occasion for you and your guests. In addition to the music you’ll be hearing tonight, we’ve supplied a song playlist for your convenience. The list is just a part of what the band has done at prior affairs. If you don’t see your favorite songs listed, please ask. Every concern and detail for your musical tastes will be held in the highest regard. Please inquire regarding the many options available. Rhapsody Members: • VOCALS, ACOUSTIC GUITAR, BASS GUITAR……………………….…CHARLIE D’ORIA • VOCALS AND PERCUSSION……..……………………….……………….ELLEN DUMLAO • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES..………….…………….……WILL COLEMAN • VOCALS, KEYBOARD, TRUMPET………………………………….……….GREG WARNO • VOCALS………………………………………..………………………….…HEATHER LITTLE • GUITAR AND VOCALS……………………………………………………….STEVE BRIODY • SAXOPHONE AND GUITAR……………………………….…………………..JON PEREIRA • DRUMS, PERCUSSION AND VOCALS….………………………………..…PAUL CAPUTO www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 — 7777 #Skylineorchestras DANCE: 867 — 5309 — Tommy Tutone 100% (Pure Love) Domino — Jessie J 1999 — Prince Don’t Leave Me This Way — Thelma Houston 24K Magic — Bruno Mars Don’t Phunk with My Heart — Black Eyed Peas A Little Party Never Killed Nobody — Fergie Don’t Start Now — Dua Lipa Accidentally In Love — Counting Crows