Globalisation, the West Midlands Auto Cluster, and the End of MG Rover Bailey, D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 2016 Richard Has Been a Morgan Dealer, Racer, Owner and Enthusiast for Over 35 Years and Runs the Business with His Daughter Helen Who Joined Him in 2001

September 2016 Richard has been a Morgan dealer, racer, owner and enthusiast for over 35 years and runs the business with his daughter Helen who joined him in 2001. John our Sales Manager heads up our team and has been with us since 2012. George looks after the workshop team of Rui, Charlotte, Rupert, Paul, Steve and James. This is what we do: New Morgan Sales: We have demonstrators of all the current model range and have early build slots available for all models. We are happy to part exchange your current Morgan. Call if you would like a test drive. Used cars: We carry a large stock of used cars and are always looking for more! Let us know if you are thinking of selling your Morgan. We have current stock from a 1950s flat rad to a 2013 Roadster. We also carry the largest stock of race cars in the UK. Race preparation: We regularly prepare and look after over 20 Morgans, including historic race cars for events such as Goodwood, Le Mans Classic and other prestigious events both at home and abroad and can offer customers an arrive and drive service. Restoration: We are regularly restoring Morgans to a very high standard, recent projects include a 1963 +4 Supersport, 1970’s +8 and a +4 TR. We also have a trim shop and paint shop on-site. Performance upgrades: Sports exhausts, manifolds, re-maps, axle upgrades, suspension upgrades, sticky tyres – let us know what you want to achieve! Parts and Service: We stock a huge number of parts for all Morgans and have a fantastic team of factory trained mechanics to look after your car and carry out routine servicing, MOTs and all general maintenance. -

Automotive Sector in Tees Valley

Invest in Tees Valley A place to grow your automotive business Invest in Tees Valley Recent successes include: Tees Valley and the North East region has April 2014 everything it needs to sustain, grow and Nifco opens new £12 million manufacturing facility and Powertrain and R&D plant develop businesses in the automotive industry. You just need to look around to June 2014 see who is already here to see the success Darchem opens new £8 million thermal of this growing sector. insulation manufacturing facility With government backed funding, support agencies September 2014 such as Tees Valley Unlimited, and a wealth of ElringKlinger opens new £10 million facility engineering skills and expertise, Tees Valley is home to some of the best and most productive facilities in the UK. The area is innovative and forward thinking, June 2015 Nifco announces plans for a 3rd factory, helping it to maintain its position at the leading edge boosting staff numbers to 800 of developments in this sector. Tees Valley holds a number of competitive advantages July 2015 which have helped attract £1.3 billion of capital Cummins’ Low emission bus engine production investment since 2011. switches from China back to Darlington Why Tees Valley should be your next move Manufacturing skills base around half that of major cities and a quarter of The heritage and expertise of the manufacturing those in London and the South East. and engineering sector in Tees Valley is world renowned and continues to thrive and innovate Access to international markets Major engineering companies in Tees Valley export Skilled and affordable workforce their products around the world with our Tees Valley has a ready skilled labour force excellent infrastructure, including one of the which is one of the most affordable and value UK’s leading ports, the quickest road connections for money in the UK. -

P 01.Qxd 6/30/2005 2:00 PM Page 1

p 01.qxd 6/30/2005 2:00 PM Page 1 June 27, 2005 © 2005 Crain Communications GmbH. All rights reserved. €14.95; or equivalent 20052005 GlobalGlobal MarketMarket DataData BookBook Global Vehicle Production and Sales Regional Vehicle Production and Sales History and Forecast Regional Vehicle Production and Sales by Model Regional Assembly Plant Maps Top 100 Global Suppliers Contents Global vehicle production and sales...............................................4-8 2005 Western Europe production and sales..........................................10-18 North America production and sales..........................................19-29 Global Japan production and sales .............30-37 India production and sales ..............39-40 Korea production and sales .............39-40 China production and sales..............39-40 Market Australia production and sales..........................................39-40 Argentina production and sales.............45 Brazil production and sales ....................45 Data Book Top 100 global suppliers...................46-50 Mary Raetz Anne Wright Curtis Dorota Kowalski, Debi Domby Senior Statistician Global Market Data Book Editor Researchers [email protected] [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Paul McVeigh, News Editor e-mail: [email protected] Irina Heiligensetzer, Production/Sales Support Tel: (49) 8153 907503 CZECH REPUBLIC: Lyle Frink, Tel: (49) 8153 907521 Fax: (49) 8153 907425 e-mail: [email protected] Tel: (420) 606-486729 e-mail: [email protected] Georgia Bootiman, Production Editor e-mail: [email protected] USA: 1155 Gratiot Avenue, Detroit, MI 48207 Tel: (49) 8153 907511 SPAIN, PORTUGAL: Paulo Soares de Oliveira, Tony Merpi, Group Advertising Director e-mail: [email protected] Tel: (35) 1919-767-459 Larry Schlagheck, US Advertising Director www.automotivenewseurope.com Douglas A. Bolduc, Reporter e-mail: [email protected] Tel: (1) 313 446-6030 Fax: (1) 313 446-8030 Tel: (49) 8153 907504 Keith E. -

The TVR Car Club

The TVR Car Club Vithout the support of the TVR Car Club 40 regfunal meetings nationwide from Dorser «r (TVRCC) and irs members, this book rvould simply North Easc Scotiand and frorrr Nonhern Ireland «r not have heen possible. If you orvn a TVR or are Suffolk. Many rneerings have rheir own, private rntere.reJ in them. j,'ining rhe Cluh pur' y,'u rn rooms in puhs or hotels and arrange guest speakers touchwithmanyotherlike-mindedpeople.Thefol- «r talk on a variety ofTVR-related topics- The Re- Iowing Club description rvas writteo by Ralph Dodds. gional Organisers also plan regular social garherings Forned in London in 1962 by a small band of and visits ro classic carshows and events where they enrhrr.ia'r.. rhc TVRCC i. n,s .rne.'irhe pr.mier can.nreal r he w,'rJ oiTVR. Manr regr,,ns.rrg"nr.e one make car clubs in the country with a melnber- theirown track days at local circuits around rhe coun- ship of over 4,500, carering for owners ofall TVRs rry rvhere you crn learn to use the po$,er of your fron the earliest TVR Coupe No I right up to the TVR in safety. There are often professional TVR iatest Cerbera and also forenrhusiasrs of the marque, Tuscan racing drners on hand to advise and help wherher an owner or not. you «r improve your skills. TVR was lixmed in 1947 by TrevorVilkinson (u,ho gave his narrre to the trake TreVoR) in Club Office Blrclp,r,l rs Trevcar M,,r,.r, He hurlr- hr. -

Alpine Loop a Success Sepmber Evenfs

A Chapter of the North American MGB Register BrtishMotor Cluh of Utoh Volume14 Number 2 prizes,as well. After we're finished at the sepmberEvenfs DQ, we'll seewhat develops. AlpineLoop a The seasonis still in full bloom. so So bring your car and your favorite co- it's too to put the car up for the driver for food fun and prizes.To donate success winter. a look at what the BMCU has prizes for or additional information, By Karen Bradakis in store contactBill Robinsonat947-9480 or 947- 5750. At 9AM on a cloudymorning, August 18, Miner's Parade. Unforhrnately,the peopleand British carsbegan to gatho ut is later dranthis event,which lVlount Nebo Fall Color Run. On the Southeastcomer of the Southtown took on Monday, September3rd Saturday,September 29,we'll renewthe Mall parkinglot. Somepeople brought (Labor in Park City. The meet-up BMCU traditim of circurnnavigatingMt. itemsto donateto be givan awayto lucky point was SwedeAlley, with the parade Nebo to partakeof brisk air and fall color. ticketholders later on at the pioric. down Main Streetin Park CiA. This is a long (200+miles) but very gathered After the the groupheaded to the enjoyabletour and will treat your eyesand The srmcame out as the drivers at City Park a reservedparking al.ea'- cleanyour exhaustvalves. lOAM for a brief meetingto discussthe thanksto efforts of Floyd lnman-and route to be takento reachthe first (pt| stop a plcnlc . Look for an accountofthis Rendezvousat the R C. Willey Clearance in Alpine. The drive beganwith over2O event in comingmsrths. Outlet,90l0 S. -

Aston Martin Lagonda Da

ASTON MARTIN LAGONDA MARTIN LAGONDA ASTON PROSPECTUS SEPTEMBER 2018 ASTON MARTIN LAGONDA PROSPECTUS SEPTEMBER 2018 591176_AM_cover_PROSPECTUS.indd All Pages 14/09/2018 12:49:53 This document comprises a prospectus (the “Prospectus”) relating to Aston Martin Lagonda Global Holdings plc (the “Company”) prepared in accordance with the Prospectus Rules of the Financial Conduct Authority of the United Kingdom (the “FCA”) made under section 73A of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (“FSMA”), which has been approved by the FCA in accordance with section 87A of FSMA and made available to the public as required by Rule 3.2 of the Prospectus Rules. This Prospectus has been prepared in connection with the offer of ordinary shares of the Company (the “Shares”) to certain institutional and other investors described in Part V (Details of the Offer) of this Prospectus (the “Offer”) and the admission of the Shares to the premium listing segment of the Official List of the UK Listing Authority and to the London Stock Exchange's main market for listed securities ("Admission"). This Prospectus updates and replaces in whole the Registration Document published by Aston Martin Holdings (UK) Limited on 29 August 2018. The Directors, whose names appear on page 96 of this Prospectus, and the Company accept responsibility for the information contained in this Prospectus. To the best of the knowledge of the Directors and the Company, who have taken all reasonable care to ensure that such is the case, the information contained in this Prospectus is in accordance with the facts and does not omit anything likely to affect the import of such information. -

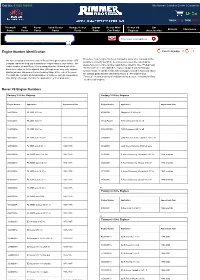

Engine Number Identification Rover V8 Engine Numbers Search by Part No. Or Description

Call Us: 01522 568000 My Account | Customer Service | Contact Us Items: 0 | Total £0.00 Triumph MG Rover Land Rover Range Rover Jaguar Rover Mini Rover V8 Car Brands Clearance Parts Parts Parts Parts Parts Parts Car Parts Engines Accessories Enter your email address Search By Part No. or Description Engine Number Identification Select Language ▼ ▼ Therefore, if your engine has been changed at some time, it should still be We have included a reference chart of Rover V8 engine numbers from 1970 possible to correctly identify it. To ensure you receive the correct parts, onwards, which will help you to identify the engine fitted to your vehicle. The please have your engine number ready before ordering. Note: "Pulsair" and engine number of most Rover V8s is stamped on the left hand side of the "Air Injection" are terms applied to engines equipped with Air Rail type block deck, adjacent to the dipstick tube, although some very early engines cylinder heads; ie cylinder heads with steel pipes located in holes just above had the number stamped on the bellhousing flange at the rear of the block. the exhaust ports (fitted to carb Range Rover & TR8 engines only). The chart also contains a brief description of features, such as compression "Detoxed" refers to a variety of emission control devices - including Air Rails ratio and gearbox type and also the approximate year of production. - fitted to carb engines. Rover V8 Engine Numbers Factory 3.5 Litre Engines Factory 3.9 Litre Engines Engine Number Application Approximate Year Engine Number Application -

Report on the Affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, Mg Rover Group Limited and 33 Other Companies Volume I

REPORT ON THE AFFAIRS OF PHOENIX VENTURE HOLDINGS LIMITED, MG ROVER GROUP LIMITED AND 33 OTHER COMPANIES VOLUME I Gervase MacGregor FCA Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Report on the affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, MG Rover Group Limited and 33 other companies by Gervase MacGregor FCA and Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Volume I Published by TSO (The Stationery Office) and available from: Online www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail TSO PO Box 29, Norwich, NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone 0870 240 3701 TSO@Blackwell and other Accredited Agents Customers can also order publications from: TSO Ireland 16 Arthur Street, Belfast BT1 4GD Tel 028 9023 8451 Fax 028 9023 5401 Published with the permission of the Department for Business Innovation and Skills on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright 2009 All rights reserved. Copyright in the typographical arrangement and design is vested in the Crown. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. First published 2009 ISBN 9780 115155239 Printed in the United Kingdom by the Stationery Office N6187351 C3 07/09 Contents Chapter Page VOLUME -

November 2020

The official newsletter of The Revs Institute Volunteers The Revs Institute 2500 S. Horseshoe Drive Naples, Florida, 34104 (239) 687-7387 Editor: Eric Jensen [email protected] Assistant Editor: Morris Cooper Volume 26.3 November 2020 Thanks to this month’s Chairman’s contributors: Chip Halverson Notes Joe Ryan Mark Kregg As I sit here and write this on 11/4, even though we do not have a Susann Miller winner in the Presidential election from yesterday, I am happy to get Mark Koestner one more thing from 2020 off my plate. Only 2 months left to go in 2020, thank goodness. It has been quite a year. Susan Kuehne As always, in anticipation of reopening, Revs Institute has all safety Inside this protocols and guidelines in place, but at present no opening date has November Issue: been released. Many of our volunteers have attended our “Returning with Confidence” training session either in person or online. Volunteer Cruise-In 2 I have received official word from Carl Grant that the museum intends Tappet Trivia 3 to remain closed to the public until the early January, however management will continue to monitor and reevaluate the situation as New Road Trip 4 things progress. Automotive Forum 5 Your Board, with the assistance of Revs Institute staff, are putting Cosworth DFX 6 together some exciting opportunities for volunteers to remain engaged Motorsports 2020 10 while the museum is closed to the public, so be sure to monitor your email for the most up-to-date news. I would like to thank Susan for her Tappet Tech 16 efforts to get us interesting and informative links on a regular basis. -

Annual Report 2018/19 (PDF)

JAGUAR LAND ROVER AUTOMOTIVE PLC Annual Report 2018/19 STRATEGIC REPORT 1 Introduction THIS YEAR MARKED A SERIES OF HISTORIC MILESTONES FOR JAGUAR LAND ROVER: TEN YEARS OF TATA OWNERSHIP, DURING WHICH WE HAVE ACHIEVED RECORD GROWTH AND REALISED THE POTENTIAL RATAN TATA SAW IN OUR TWO ICONIC BRANDS; FIFTY YEARS OF THE EXTRAORDINARY JAGUAR XJ, BOASTING A LUXURY SALOON BLOODLINE UNLIKE ANY OTHER; AND SEVENTY YEARS SINCE THE FIRST LAND ROVER MOBILISED COMMUNITIES AROUND THE WORLD. TODAY, WE ARE TRANSFORMING FOR TOMORROW. OUR VISION IS A WORLD OF SUSTAINABLE, SMART MOBILITY: DESTINATION ZERO. WE ARE DRIVING TOWARDS A FUTURE OF ZERO EMISSIONS, ZERO ACCIDENTS AND ZERO CONGESTION – EVEN ZERO WASTE. WE SEEK CONSCIOUS REDUCTIONS, EMBRACING THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY AND GIVING BACK TO SOCIETY. TECHNOLOGIES ARE CHANGING BUT THE CORE INGREDIENTS OF JAGUAR LAND ROVER REMAIN THE SAME: RESPONSIBLE BUSINESS PRACTICES, CUTTING-EDGE INNOVATION AND OUTSTANDING PRODUCTS THAT OFFER OUR CUSTOMERS A COMPELLING COMBINATION OF THE BEST BRITISH DESIGN AND ENGINEERING INTEGRITY. CUSTOMERS ARE AT THE HEART OF EVERYTHING WE DO. WHETHER GOING ABOVE AND BEYOND WITH LAND ROVER, OR BEING FEARLESSLY CREATIVE WITH JAGUAR, WE WILL ALWAYS DELIVER EXPERIENCES THAT PEOPLE LOVE, FOR LIFE. The Red Arrows over Solihull at Land Rover’s 70th anniversary celebration 2 JAGUAR LAND ROVER AUTOMOTIVE PLC ANNUAL REPORT 2018/19 STRATEGIC REPORT 3 Introduction CONTENTS FISCAL YEAR 2018/19 AT A GLANCE STRATEGIC REPORT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 3 Introduction 98 Independent Auditor’s report to the members -

Sfr Solo 12 & 13 Regional 13 & 14

VOL. 58 | DECEMBER 2017 The official publication of the San Francisco Region of the Sports Car Club Of America SFR SOLO 12 & 13 YEAR-END FUN PHOTOS REGIONAL 13 & 14 p. 10 FEATURING THE RDC ENDURO p. 18 $1,600 Driver School SpecRacer Rental* SpecRacers are now 6 Seconds faster than a Spec Miata at ThunderHill SpecRacer Gen 3 Services Benefits • SRF Rentals & Arrive & Drive Though they look the same, the GEN DECEMBER 2017 • Cars and Parts Sales • Proven Track Reliability 3 was introduced in 2015. These cars • Trackside Support for Your Car • Proven Maintenance are everything you could ask for in a On the Cover: #36 Lawerence Bacon, #22 Jerry Kroll, and #18 Jeff Read. By Ron Cabral. • Fast and Sorted Cars spec car. Lightweight and fast, the Photo Above: #47 Joe Reppert. By Ron Cabral. • Driver Coaching GEN 3 raises the bar in an already • Maintenance& Repairs AccelRaceTek LLC exciting class. • Transportation 5 Free Test Day at Thunderhill 12 Sacramento Solo Enduro 18 SFR Double Regional 13 & 14, Featuring Los Gatos, CA 95032 FEATURES the RDC Enduro • At Track Repairs – Including Welding (669) 232-4844 5 Letter to the Editor 13 Full Body Contact www.AccelRaceTek.com 26 SFR Solo Round 13 6 Wheelworks 15 How To Qualify for the 2018 Runoffs * See details on our website. 28 Thunderhill Report 8 SFR Solo Round 12 16 Notes from the Archive 10 Year-End Fun Photos Rentals om IN EVERY ISSUE 4 Calendar 5 Travel Tech 29 Race Car Rentals 30 The Garage: Classified Ads Builds .c The views expressed in The Wheel are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of San Francisco Region or the SCCA. -

Ditas-Product-Catalogue-2021.Pdf

2021 PRODUCT CATALOGUE ÜRÜN KATALOĞU ditas.com.tr /Ditas /ditas_dogan /ditasdogan /ditasdogan CONTENTS İÇİNDEKİLER Abarth 3 Alfa Romeo 4 – 5 Alpina 6 Alpine 7 Aston Martin 8 Audi 9 – 12 Auto Union 13 Autobianchi 14 – 15 Bedford 16 BMC 17 – 27 BMW 28 – 29 Buick 30 Cadillac 31 Carbodies 32 Chevrolet 33 Chrysler 34 Citroën 35 – 43 Dacia 44 – 45 Daewoo 46 DAF 47 – 61 Daimler 62 Dodge 63 ERF 64 Fiat 65 – 82 Ford 83 – 108 FSO 109 – 111 GMC 112 Hyundai 113 – 114 Irisbus 115 – 116 Irizar 117 – 121 Isuzu 122 – 124 IVECO 125 – 145 Jaguar 146 Jeep 147 KIA 148 Lada 149 – 151 Lancia 152 – 156 Land Rover 157 – 158 LDV 159 Lexus 160 LTI 161 MAN 162 – 193 Maserati 194 Massey Ferguson 195 Mazda 196 – 197 Mega 198 Mercedes-Benz 199 – 292 MG 293 Mitsubishi 294 – 297 NEOPLAN 298 – 300 Nissan 301 – 305 Oldsmobile 306 Opel 307 – 319 Peugeot 320 – 331 Pininfarina 332 Plaxton 333 Porsche 334 Premier 335 Proton 336 Ranger 337 Rayton Fissore 338 Renault 339 – 356 Renault Trucks 357 – 375 Rover 376 Saab 377 – 378 Scania 379 – 394 SEAT 395 – 399 Setra 400 – 404 Skoda 405 – 409 Subaru 410 Talbot 411 Temsa 412 Toyota 413 Volvo 414 – 449 VW 450 – 465 Zastava 466 DA1-2947 Track Control Arm (Salıncak kolu) Model (Model): OEM Num. (OEM No): Features (Özellik): GRANDE PUNTO (199_) LINEA 51783056 Cone Size [mm] : 16 (323_) MITO (955_) QUBO 55703627 Bore Ø [mm] : 12,2 (225_) 51783056 55703627 DA1-2948 Track Control Arm (Salıncak kolu) Model (Model): OEM Num. (OEM No): Features (Özellik): GRANDE PUNTO (199_) LINEA 51783057 Length 1/ Length 2 [mm] : (323_) MITO (955_) QUBO 55703629 283/288.1 (225_) 51783057 55703629 DA1-937 Track Control Arm (Salıncak kolu) Model (Model): OEM Num.