Mastering Chess Middlegames: Lectures from the All-Russian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FM ALISA MELEKHINA Is Currently Balancing Her Law and Chess Careers. Inside, She Interviews Three Other Lifelong Chess Players Wrestling with a Similar Dilemma

NAKAMURA WINS GIBRALTAR / SO FINISHES SECOND AT TATA STEEL APRIL 2015 Career Crossroads FM ALISA MELEKHINA is currently balancing her law and chess careers. Inside, she interviews three other lifelong chess players wrestling with a similar dilemma. IFC_Layout 1 3/11/2015 6:02 PM Page 1 OIFC_pg1_Layout 1 3/11/2015 7:11 PM Page 1 World’s biggest open tournament! 43rd annual WORLD OPEN Hyatt Regency Crystal City, near D.C. 9rounds,June30-July5,July1-5,2-5or3-5 $210,000 Guaranteed Prizes! Master class prizes raised by $10,000 GM & IM norms possible, mixed doubles prizes, GM lectures & analysis! VISIT OUR NATION’S CAPITAL SPECIAL FEATURES! 4) Provisional (under 26 games) prize The World Open completes a three 1) Schedule options. 5-day is most limits in U2000 & below. year run in the Washington area before popular, 4-day and 3-day save time & 5) Unrated not allowed in U1200 returning to Philadelphia in 2016. money.New,leisurely6-dayhas three1- though U1800;$1000 limit in U2000. $99 rooms, valet parking $6 (if full, round days. Open plays 5-day only. 6) Mixed Doubles: $3000-1500-700- about $7-15 nearby), free airport shuttle. 2) GM & IM norms possible in Open. 500-300 for male/female teams. Fr e e s hutt l e to DC Metro, minutes NOTECHANGE:Mas ters can now play for 7) International 6/26-30: FIDE norms from Washington’s historic attractions! both norms & large class prizes! possible, warm up for main event. Als o 8sections:Open,U2200,U2000, 3) Prize limit $2000 if post-event manyside events. -

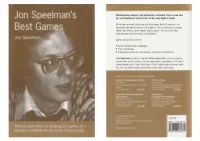

Mind-Bending Analysis and Instructive Comment from a Man Who Has Participated in World Chess at the Very Highest Levels

Mind-bending analysis and instructive comment from a man who has participated in world chess at the very highest levels World championship candidate and three-times British Champion Jon Speelman annotates the best of his games. He is renowned as a great fighter and analyst, and a highly original player. This book provides entertainment and instruction in abundance. Games and stories from his: • World Championship campaigns • Chess Olympiads • Toi>level grandmaster tournaments, including the World Cup Jon Speelman is one of only two British players this century to gain a place in the world's top five. He has reached the sem>finals of the world championship and is one of the stars of the English national team, which has won the silver medals three times in the chess Olympiads. Jon Speelman's Best Games Jon Speelman B. T. Batsford Ltd, London First published 1997 © Jon Speelman 1997 ISBN 0 7134 6477 I British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. Contents A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, by any means, without prior permission of the publisher. Introduction 5 Typeset and edited by First Rank Publishing, Brighton and printed in Great Britain by Redwood Books, Trowbridge, Wilts Part I Growing up as a Chess player for the publishers, B. T. Batsford Ltd, Juvenilia 7 583 Fulham Road, I JS-J.Fletcher, British U-14 Ch., Rhyl1969 9 London SW6 5BY 2 JS-E.Warren, Thames Valley Open 1970 11 3 A.Miles-JS, Islington Open 1970 14 4 JS-Hanau, Nice 1971 -

Mikhalchishin Pdf Download Mikhalchishin Pdf Download

mikhalchishin pdf download Mikhalchishin pdf download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66a41babbd9615f4 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. The Center: A Modern Strategy Guide. Our BOOK OF THE WEEK is The Center: A Modern Strategy Guide by Adrian Mikhalchishin & Georg Mohr. Everyone knows that it is important to control the center. However, the methods for center control and the implications for each type of center control are not as well known. The center is such a complicated topic to understand that two schools of chess (classical and hypermodern) debated each other for decades about the occupation of the center vs. piece pressure against the center. And that's just the start, understanding of the center has developed a lot since those debates, and understanding the center is as crucial as ever. The Center: A Modern Strategy Guide teaches you typical methods to fight for the center and what to do once you obtain it, categorized by typical themes and structures. -

Iyew Euland [email protected]

32 NEW ZEALAND CI{ESS SUPPLIES P.O. Box 122 Greytown Phone: (06) 304 8484 Fax (06) 304 8485 IYew euland [email protected] - www.chess.co.nz Our book list of current chess literature sent by email on requesl Check our websitefor wooden sels, boards, electronic chess and software Plastic Chessmen'Staanton' Slltle - Club/Tournament Slandard No 280 Solid Plastic - Felt Base 95mm King $ 18.50 No 402 Solid Plastic - Felt Base Extra Weighted with 2 Queens 95mm King $ 22.00 Chess No 298 Plastic Felt Base'London Set' 98mm King $ 24.50 Official magazine ofthe New Zealand Chess Federation (Inc) Plastic Container with Clip Tight Lid for Above Sets s 7.50 Chessboards 5 l0mm' Soft Vinyl Roll-Up Mat Type (Green & White Squares) $ 7.50 450mm2 Soft Vinyl Roll-Up Mat Type (Dark Brown & White Squares) $ 10.00 Yol32 Number 5 October 2005 450mm' Folding Vinyl (Dark Brown & Off White Squares) $ 19.50 480mm' Folding Thick Cardboard (Green & Lemon Squares) $ 7.50 450mm x 470mm Soft Vinyl Roll-Up Mat Type (Green & White Squares) $ 7.50 450m2 Hard Vinyl Semi Flexible Non Folding (Very Dark Brown and Off ll/hite Sqmrel $ 11.00 Chess Move Timers (Clocks) 'Turnier'German Made Popular Club Clock - Light Brown Brown Vinyl Case $ 80.00 'Exclusiv' German Made as Above in Wood Case $ 98.00 'Saitek'Digital Chess Clock & Game Timer $112.00 DGT XL Chess Clock & Game Timer (FIDE) $r45.00 Club and Tournament Stalionery Pairing/Result Cards - l l Round NZCF Format $ 0.10 Cross Table/Result Wall Chart 430mm x 630mm $ 3.00 I I Rounds for 20 Players or 6 Rounds for -

Rights Guide Children's Books

Rights Guide Children’s Books Spring 2021 Complete List Knesebeck Verlag | Holzstrasse 26 | 80469 Muenchen | Germany T +49 (0) 89 242 11 66-0 | [email protected] | www.knesebeck-verlag.de The World of the Oceans IN THE DEPTHS OF THE OCEAN In this non-fiction book for children, Dieter Braun, author of the bestselling works The World of Wild Animals and The World of the Mountains, takes a refreshing look at life below the sea as seen through a magnifying glass. His expressive illustrations take young readers on a tour from the depths of the oceans to the North Sea, with scary sharks, majestic whales and friendly dolphins, giant octopuses, sea turtles, crabs or sea horses and all the things just waiting to be discovered on beaches. Readers can also find out more about the different professions in which people work on and in the seas, marine sports, and also discover famous lighthouses and learn about weather phenomena such as the dreaded sea fog. The colourful illustrations are accompanied by brief texts with facts and figures about the oceans of our planet. Illustrator/Author: Dieter Braun THE AUTHOR Dieter Braun works in Hamburg as a freelance illustrator and author of books for children. He studied communication design at the Folkwangschule in Essen. His clients include Time Magazine, New York Times, Newsweek, Stern, Geo, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Zeit, WWF to name but a few. His non-fiction wildlife books The World of Wild Animals have been translated into 11 languages. USPs The new masterpiece by Dieter Braun, author of the bestselling -

1987 October 3

'. ,.- ~. -- . ~ t .· •..•-.. ~ . :.-~ ~.:- ... ~·': ... •; ·. ,. .. .· ·t4"1tffl,:.,• ~ .....•.. .,;--< Unlike other aerosols l ··.? 'or wick-type deodorisers. Nilodordoesn't just cover one smell with''another. '$.Oviet ! squeeze Nilodor chemically -~y, ~airray ·Cliandler merges with the odour• carrying gases in the air --~ · ··A· · · , S I WRITE, · two of the three RUY LOPEZ and neutralises them. · · World .Championship Qualifying G SAX N SHORT So all your nose is )eft e4 es · Interzonal tournaments have 1. to enjoy is freshness. · · · ended, with quite sensational re• 2. Nf3 Ne& 3. BbS a6 Nilodor is safe and easy sults irr both. In the modest Yugoslav 4. Ba4 Nf6 to use throughout your town of Subotica the Soviets were 5. 0-0 Be7 squeezed out completely when England's 6. Ret bS home. Because it's Nigel Short and Jonathan Speelman were 7. Bbl d6 concentrated and more joined by Hungary's Gyula Sax in a tie for 8. c3 · 0-0 efficient, Nilodor is the first place. In Szirak in Hungary, the 9. h3 Bb7 most economical young grandmaster Johann Hjartason has 10. d4 Re8 become a hero of his native Iceland by Maybe you would like a nice draw today deodoriser you can buy. tying for first with Valery Salov of, the with 11. Ng5 R/8 12. Nf3 Re8? USSR. The third qualifying spot from 11. a4' ·. # Szirak was tied between Hungary's Lajos No thank you. I have a feeling I might need Portisch and England's John Nunn. A an extra half point later in this tournament. 11. ... h6 play-off will, have to be held to decide · 12. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

Monarch Assurance International Open Chess

Isle of Man (IoM) Open The event of 2016 definitely got the Isle of Man back on the international chess map! Isle of Man (IoM) Open has been played under three different labels: Monarch Assurance International Open Chess Tournament at the Cherry Orchard Hotel (1st-10th), later Ocean Castle Hotel (11th-16th), always in Port Erin (1993 – 2007, in total 16 annual editions) PokerStars Isle of Man International (2014 & 15) in the Royal Hall at the Villa Marina in Douglas Chess.com Isle of Man International (since 2016) in the Royal Hall at the Villa Marina in Douglas The Isle of Man is a self-governing Crown dependency in the Irish Sea between England and Northern Ireland. The island has been inhabited since before 6500 BC. In the 9th century, Norsemen established the Kingdom of the Isles. Magnus III, King of Norway, was also known as King of Mann and the Isles between 1099 and 1103. In 1266, the island became part of Scotland and came under the feudal lordship of the English Crown in 1399. It never became part of the Kingdom of Great Britain or its successor the United Kingdom, retaining its status as an internally self-governing Crown dependency. http://iominternationalchess.com/ For a small country, sport in the Isle of Man plays an important part in making the island known to the wider world. The principal international sporting event held on the island is the annual Isle of Man TT motorcycling event: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sport_in_the_Isle_of_Man#Other_sports Isle of Man also organized the 1st World Senior Team Chess Championship, In Port Erin, Isle Of Man, 5-12 October 2004 http://www.saund.co.uk/britbase/worldseniorteam2004/ Korchnoi who had to hurry up to the forthcoming 2004 Chess Olympiad at Calvià, agreed to play the first four days for the team of Switzerland which took finally the bronze medal, performing at 3.5/4, drawing vs. -

The Livonian Knight Selected Games of Alvis Vitolins

The Livonian Knight Selected Games of Alvis Vitolins Zigurds Lanka, Edvins Kengis, Janis Klovans and Janis Vitomskis The Livonian Knight: Selected Games of Alvis Vitolins Authors: Zigurds Lanka, Edvins Kengis, Janis Klovans and Janis Vitomskis Translation by Alexei Zakharov and Retorika Publishing House, Riga Typesetting by Andrei Elkov (www.elkov.ru) Photos provided by the authors and the Latvian Chess Federation Front cover photo taken by M. Rabkin, 1980 © LLC Elk and Ruby Publishing House, 2021. All rights reserved First published in Latvia in Latvian in 2008 by Liepaja University Press Follow us on Twitter: @ilan_ruby www.elkandruby.com ISBN 978-5-6045607-7-8 Note the analysis in this book was updated in 2021 by International Master Grigory Bogdanovich. The publisher wishes to thank Inga Ronce of Liepaja University and Matiss Silis of Riga Stradins University as well as the following Latvian chess players for their assistance in the publication of this book in English: Alberts Cimins, Janis Grasis, Andris Tihomirovs and Alexei Zhuchkov. 3 Contents Index of Games .........................................................................................................4 Foreword to the English edition – True chess has no limits! .......................5 Foreword by the Authors .......................................................................................8 Introduction – An Innovator and Pioneer ..................................................... 10 Chapter 1: Wedge in the Center of the Board ............................................. -

Mikhail Botvinnik Sixth World Chess Champion

Mikhail Botvinnik Sixth World Chess Champion Isaak & Vladimir Linder Foreword by Andy Soltis Game Annotations by Karsten Müller World Chess Champions Series 2020 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 1 Mikhail Botvinnik Sixth World Chess Champion ISBN: 978-1-949859-16-4 (print) ISBN: 949859-17-1 (eBook) © Copyright 2020 Vladimir Linder All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Cover by Janel Lowrance Printed in the United States of America 2 Table of Contents Foreword by Andy Soltis Signs and Symbols Everything about the World Championships Prologue Chapter 1 His Life and Fate His Childhood and Youth His Family His Personality His Student Life The Algorithm of Mastery The School of the Young and Gifted Political Survey Guest Appearances Curiosities The Netherlands Great Britain Chapter 2 Matches, Tournaments, and Opponents AVRO Tournament, 1938 Alekhine-Botvinnik: The Match That Did Not Happen Alekhine Memorial, 1956 Amsterdam, 1963 and 1966 Sergei Belavienets Isaak Boleslavsky Igor Bondarevsky David Bronstein Wageningen, 1958 Wijk aan Zee, 1969 World Olympiads -

Brekke the Chess Saga of Fridrik Olafsson

ØYSTEIN BREKKE | FRIDRIK ÓLAFSSON The Chess Saga of FRIÐRIK ÓLAFSSON with special contributions from Gudmundur G. Thórarinsson, Gunnar Finnlaugsson, Tiger Hillarp Persson, Axel Smith, Ian Rogers, Yasser Seirawan, Jan Timman, Margeir Pétursson and Jóhann Hjartarson NORSK SJAKKFORLAG TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword by President of Iceland, Guðni Th. Jóhannesson ..................4 Preface .........................................................5 Norsk Sjakkforlag Fridrik Ólafsson and his Achievements by Gudmundur G. Thorarinsson .....8 Øystein Brekke Haugesgate 84 A Chapter 1: 1946 – 54 From Childhood to Nordic Champion .............10 3019 Drammen, Norway Mail: [email protected] Chapter 2: 1955 – 57 National Hero and International Master ...........42 Tlf. +47 32 82 10 64 / +47 91 18 91 90 www.sjakkforlag.no Chapter 3: 1958 – 59 A World Championship Candidate at 23 ..........64 www.sjakkbutikken.no Chapter 4: 1960 – 62 Missed Qualification in the 1962 Interzonal ........94 ISBN 978-82-90779-28-8 Chapter 5: 1963 – 68 From Los Angeles to Reykjavik ..................114 Authors: Øystein Brekke & Fridrik Ólafsson Chapter 6: 1969 – 73 The World’s Strongest Amateur Player ............134 Design: Tommy Modøl & Øystein Brekke Proof-reading: Tony Gillam & Hakon Adler Chapter 7: 1974 – 76 Hunting New Tournament Victories ..............166 Front page photo: Chapter 8: 1977 – 82 Brilliant Games & President of FIDE ..............206 Fridrik in the Beverwijk tournament 1961. (Harry Pot, Nationaal Archief) Chapter 9: 1983 – 99 Fridrik and the Golden Era of Icelandic Chess ....246 Production: XIDE AS & Norsk Sjakkforlag Chapter 10: 2000 – An Honorary Veteran Still Attacking ..............262 Cover: XIDE AS & Norsk Sjakkforlag Printing and binding: XIDE AS Games in the Book ................................................282 Paper: Multiart Silk 115 gram Opening index ....................................................284 Copyright © 2021 by Norsk Sjakkforlag / Øystein Brekke Index of opponents, photos and illustrations ...........................285 All rights reserved. -

Magnus Carlsen (15) “Endelig” Norgesmester Foto: Berg Johansen Bjørn

Magnus Carlsen (15) “endelig” norgesmester Foto: Bjørn Johansen Berg Foto: nr. 5 2006 D`iVc=VbVg;did/?Zch=Vj\Zc 0RINSESSENP»ERTENKANVIKLAREOSSUTEN -ENKONGER DRONNINGER BNDER LPERE OGSPRINGEREERDETGODPLASSTIL ,ÕÃvÀÌÌÊ©]ÊÕvÀiÊ>ÌÃvCÀi]Ê Þ}}i}iÊÛiÀÌiÀÊ}ÊÀi}iÊ «ÀÃiÀÊ}©ÀÊÛ>`ÀiÀ iÊÌÊiÌÊÃÌÀ>Ìi}ÃÊÛ>}ÊvÀÊÃ>ëiÀiÊ ÃÊ >ÀÊLi ÛÊvÀÊ}`Ê>ÌÌiéÛ]ÊiÌiÊ`iÊÃ>ÊëiÊÃ>ÊiiÀÊ iÀÊÕÌiÊ«FÊÀiÃiÊÊ>iÌÊCÀi`°Ê/>ÊÌ>ÌÊi`ÊÛ>`ÀiÀ iiiÊ `ÀiÌiÊvÀÊ«Àð iÀÊvÀ>ÃÊwiÀÊ`ÕÊ«FÊÛFÀiÊiÌÌÃ`iÀ\ÊÜÜÜ°Û>`ÀiÀ i° 3JAKKANNONSER?XINDD I n n h o l d Nr. 5 • 2006 • årg 72 Leder..................................................................................4 Midnight.Sun.Chess.Challenge.......................................5 Stikkampen.Agdestein-Carlsen................................... 12 Stikkampen.Porsgrunn-Asker......................................17 Politiken.Cup.................................................................. 23 Du.trekker....................................................................... 25 Senior-VM....................................................................... 26 Biel....................................................................................27 Nilssen Foto: Tore EM.for.ungdom.............................................................. 30 Kronikker........................................................................ 32 Forhåndsrapport.Telioserien........................................ 34 Kombinasjonsartikkel................................................... 35 Gausdal............................................................................37