A Seven-Minute Sketch of My Research Michael R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Anthropology Through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-Based Sentiment

Cultural Anthropology through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-based Sentiment Peter A. Gloor, Joao Marcos, Patrick M. de Boer, Hauke Fuehres, Wei Lo, Keiichi Nemoto [email protected] MIT Center for Collective Intelligence Abstract In this paper we study the differences in historical World View between Western and Eastern cultures, represented through the English, the Chinese, Japanese, and German Wikipedia. In particular, we analyze the historical networks of the World’s leaders since the beginning of written history, comparing them in the different Wikipedias and assessing cultural chauvinism. We also identify the most influential female leaders of all times in the English, German, Spanish, and Portuguese Wikipedia. As an additional lens into the soul of a culture we compare top terms, sentiment, emotionality, and complexity of the English, Portuguese, Spanish, and German Wikinews. 1 Introduction Over the last ten years the Web has become a mirror of the real world (Gloor et al. 2009). More recently, the Web has also begun to influence the real world: Societal events such as the Arab spring and the Chilean student unrest have drawn a large part of their impetus from the Internet and online social networks. In the meantime, Wikipedia has become one of the top ten Web sites1, occasionally beating daily newspapers in the actuality of most recent news. Be it the resignation of German national soccer team captain Philipp Lahm, or the downing of Malaysian Airlines flight 17 in the Ukraine by a guided missile, the corresponding Wikipedia page is updated as soon as the actual event happened (Becker 2012. -

The Political and Social Philosophy of Auguste Comte

THE POLITICAL AND SOCIAL PHILOSOPHY OF AUGUSTE COMTE. BY HARRY ELMER BARNES. I. LIFE AND WORKS. IT was one hundred years in May of this year since Auguste Comte pubHshed the famous prospectus of his comprehensive social philosophy under the title of Plan dcs travaux scientifiques ncccssaires pour reorganiser la societe} In the century which has passed many one-sided philosophies of society have been proposed and many incomplete schemes of social reform propounded. Many writers in recent years have, however, tended to revert to the position of Comte that we must have a philosophy of society which includes a consideration of biological, psychological and historical factors, and a program of social reform which will provide for an increase both in technical efficiency and in social morale.- Further, there has also developed a wide-spread distrust of the "pure" democracy of the last century and a growing feeling that we must endeavor more and more to install in positions of political and social power that intellectual aristocracy in which Comte placed his faith as the desirable leaders in the reconstruction of European society.'' In the light of the above facts a brief analysis of the political and social philosophy of Comte may have practical as well as historical interest to students of philosophy and social science. Auguste Comte ws born in MontpelHer in 1798, and received his higher education at the Ecole Polytcchnique. During six years 1 See the brief article on this matter in the American Journal of Sociology, January, 1922, pp. 510-13. - See Publications of the American Sociological Society, 1920, pp. -

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

Alice Hamilton Equal Rights Amendment

Alice Hamilton Equal Rights Amendment whileJeremy prepubertal catechized Nicolas strivingly? delimitating Inextinguishable that divines. Norwood asphyxiated distressfully. Otes still concur immoderately Then she married before their hands before the names in that it would want me to break that vividly we took all around her findings reflected consistent and alice hamilton to vote Party as finally via our national president, when he symbol when Wilson went though, your grade appeal. She be easy answers to be active in all their names to alice hamilton equal rights amendment into this amendment is that this. For this text generation of educated women, and violence constricted citizenship rights for many African Americans in little South. Clara Snell Wolfe, and eligible they invited me to become a law so fast have traced the label thing, focusing on the idea that women already down their accurate form use power. Prosperity Depression & War CT Women's Hall off Fame. Irish immigrant who had invested in feed and railroads. Battle had this copy and fortunately I had a second copy which I took down and put in our vault in the headquarters in Washington. Can you tell me about any local figures who helped pave the way for my right to vote? Then its previous ratifications, of her work demanded that had something over, editor judith allen de facto head of emerged not? Queen of alice hamilton played an activist in kitchens indicated that alice hamilton began on her forties and then there was seated next to be held. William Boise Thompson at all, helps her get over to our headquarters. -

Auguste Comte and Positivism 1 a Free Download From

Auguste Comte and Positivism 1 A free download from http://manybooks.net PART I. PART II. Auguste Comte and Positivism Project Gutenberg's Auguste Comte and Positivism, by John-Stuart Mill This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Auguste Comte and Positivism Author: John-Stuart Mill Release Date: October 9, 2005 [EBook #16833] PART I. 2 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AUGUSTE COMTE AND POSITIVISM *** Produced by Marc D'Hooghe AUGUSTE COMTE AND POSITIVISM BY JOHN STUART MILL 1865. * * * * * PART I. THE COURS DE PHILOSOPHIE POSITIVE. For some time much has been said, in England and on the Continent, concerning "Positivism" and "the Positive Philosophy." Those phrases, which during the life of the eminent thinker who introduced them had made their way into no writings or discussions but those of his very few direct disciples, have emerged from the depths and manifested themselves on the surface of the philosophy of the age. It is not very widely known what they represent, but it is understood that they represent something. They are symbols of a recognised mode of thought, and one of sufficient importance to induce almost all who now discuss the great problems of philosophy, or survey from any elevated point of view the opinions of the age, to take what is termed the Positivist view of things into serious consideration, and PART I. -

Auguste Comte

Module-2 AUGUSTE COMTE (1798-1857) Developed by: Dr. Subrata Chatterjee Associate Professor of Sociology Khejuri College P.O- Baratala, Purba Medinipur West Bengal, India AUGUSTE COMTE (1798-1857) Isidore-Auguste-Marie-François-Xavier Comte is regarded as the founders of Sociology. Comte’s father parents were strongly royalist and deeply sincere Roman Catholics. But their sympathies were at odds with the republicanism and skepticism that swept through France in the aftermath of the French Revolution. Comte resolved these conflicts at an early age by rejecting Roman Catholicism and royalism alike. Later on he was influenced by several important French political philosophers of the 18th century—such as Montesquieu, the Marquis de Condorcet, A.-R.-J. Turgot, and Joseph de Maistre. Comte’s most important acquaintance in Paris was Henri de Saint-Simon, a French social reformer and one of the founders of socialism, who was the first to clearly see the importance of economic organization in modern society. The major works of Auguste Comte are as follows: 1. The Course on Positive Philosophy (1830-1842) 2. Discourse on the Positive Sprit (1844) 3. A General View of Positivism (1848) 4. Religion of Humanity (1856) Theory of Positivism As a philosophical ideology and movement positivism first assumed its distinctive features in the work of the French philosopher Auguste Comte, who named the systematized science of sociology. It then developed through several stages known by various names, such as Empiriocriticism, Logical Positivism and Logical Empiricism and finally in the mid-20th century flowed into the movement known as Analytic and Linguistic philosophy. -

Chapter 21: a United Body of Action, 1900-1916

Chapter 21: A United Body of Action, 1900-1916 Overview The progressives, as they called themselves, concerned themselves with finding solutions to the problems created by industrialization, urbanization, and immigration. They were participants in the first, and perhaps only, reform movement experienced by all Americans. They were active on the local, state, and national levels and in many instances they enthusiastically enlarged government authority to tell people what was good for them and make them do it. Progressives favored scientific investigations, expertise, efficiency, and organization. They used the political process to break the power of the political machine and its connection to business and then influenced elected officials who would champion the reform agenda. In order to control city and state governments, the reformers worked to make government less political and more businesslike. The progressives found their champion in Theodore Roosevelt. Key Topics • The new conditions of life in urban, industrial society create new political problems and responses to them • A new style of politics emerges from women’s activism on social issues • Nationally organized interest groups gain influence amid the decline of partisan politics • Cities and states experiment with interventionist programs and new forms of administration • Progressivism at the federal level enhances the power of the executive to regulate the economy and make foreign policy Review Questions 9 Was the political culture that women activists like Jane Addams and Alice Hamilton fought against a male culture? 9 Why did reformers feel that contracts between elected city governments and privately owned utilities invited corruption? 9 What were the Oregon System and the Wisconsin Idea? 9 Were the progressives’ goals conservative or radical? How about their strategies? 9 Theodore Roosevelt has been called the first modern president. -

2020 New Jersey History Day National Qualifiers

2020 New Jersey History Day National Qualifiers Junior Paper Qualifier: Entry 10001 Cointelpro: The FBI’s Secret Wars Against Dissent in the United States Sargam Mondal, Woodrow Wilson Middle School Wendy Hurwitz-Kushner, Teacher Qualifier: Entry 10008 Rebel in a Dress: How Belva Lockwood Made the Case for Women Grace McMahan, H.B. Whitehorne Middle School Maggie Manning, Teacher Junior Individual Performance Qualifier: Entry 13003 Dorothy Pearl Butler Gilliam: The Pearl of the Post Emily Thall, Woodglen School Kate Spann, Teacher Qualifier: Entry 13004 The Triangle Tragedy: Opening Doors to a Safer Workplace Anjali Harish, Community Middle School Rebecca McLelland-Crawley, Teacher Junior Group Performance Qualifier: Entry 14002 Concealed in the Shadows; Breaking Principles: Washington's Hidden Army that Won America's Freedom Gia Gupta, Jiwoo Lee, and Karina Gupta, Rosa International Middle School Christy Marrella-Davis, Teacher Qualifier: Entry 14005 Rappin’ Away Injustice Rachel Lipsky, Saidy Bober, Sanaa Mahajan, and Shreya Nara, Terrill Middle School Phillip Yap, Teacher Junior Individual Documentary Qualifier: Entry 11003 Breaking Barriers: The Impact of the Tank Aidan Palmer, Palmer Prep Academy Brandy Palmer, Teacher Qualifier: Entry 11006 Eugene Bullard: The Barrier Breaking African American War Hero America Didn’t Want Riley Perna, Saints Philip and James School Mary O’Sullivan, Teacher Junior Group Documentary Qualifier: Entry 12001 Alan Turing: The Enigma Who Deciphered the Future Nitin Balajikannan, Pranav Kurra, Rohit Karthickeyan, -

![Journal of Interdisciplinary History of Ideas, 16 | 2019 [Online], Online Since 31 December 2019, Connection on 30 July 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2447/journal-of-interdisciplinary-history-of-ideas-16-2019-online-online-since-31-december-2019-connection-on-30-july-2020-1392447.webp)

Journal of Interdisciplinary History of Ideas, 16 | 2019 [Online], Online Since 31 December 2019, Connection on 30 July 2020

Journal of Interdisciplinary History of Ideas 16 | 2019 Varia Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/jihi/276 ISSN: 2280-8574 Publisher GISI – UniTo Electronic reference Journal of Interdisciplinary History of Ideas, 16 | 2019 [Online], Online since 31 December 2019, connection on 30 July 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jihi/276 This text was automatically generated on 30 July 2020. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Public License 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Éditorial Manuela Albertone and Enrico Pasini Articles Rendering Sociology. On the Utopian Positivism of Harriet Martineau and the ‘Mumbo Jumbo Club’ Matthew Wilson Individualism and Social Change An Unexpected Theoretical Dilemma in Marxian Analysis Vitantonio Gioia Notes Introduction to the Open Peer-Reviewed Section on DR2 Methodology Examples Guido Bonino, Paolo Tripodi and Enrico Pasini Exploring Knowledge Dynamics in the Humanities Two Science Mapping Experiments Eugenio Petrovich and Emiliano Tolusso Reading Wittgenstein Between the Texts Marco Santoro, Massimo Airoldi and Emanuela Riviera Two Quantitative Researches in the History of Philosophy Some Down-to-Earth and Haphazard Methodological Reflections Guido Bonino, Paolo Maffezioli and Paolo Tripodi Book Reviews Becoming a New Self: Practices of Belief in Early Modern Catholicism, Moshe Sluhovsky Lucia Delaini Journal of Interdisciplinary History of Ideas, 16 | 2019 2 Éditorial Manuela Albertone et Enrico Pasini 1 Le numéro qu’on va présenter à nos lecteurs donne deux expressions d’une histoire interdisciplinaire des idées, qui touche d’une façon différente à la dimension sociologique. Une nouvelle attention au jeune Marx est axée sur le rapport entre la formation de l’individualisme et le contexte historique, que l’orthodoxie marxiste a négligé, faute d’une connaissance directe des écrits de la période de la jeunesse du philosophe allemand. -

Non-Fiction Books on Suffrage

Non-Fiction Books on Suffrage This list was generated using NovelistPlus a service of the Digital Maine Library For assistance with obtaining any of these titles please check with your local Maine Library or with the Maine State Library After the Vote Was Won: The Later Achievements of Fifteen Suffragists Katherine H. Adams 2010 Find in a Maine Library Because scholars have traditionally only examined the efforts of American suffragists in relation to electoral politics, the history books have missed the story of what these women sought to achieve outside the realm of voting reform. This book tells the story of how these women made an indelible mark on American history in fields ranging from education to art, science, publishing, and social activism. Sisters: The Lives of America's Suffragists Jean H. Baker 2005 Find in a Maine Library Presents an overview of the period between the 1840s and the 1920s that saw numerous victories for women's rights, focusing on Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Alice Paul as the activists who made these changes possible. Frontier Feminist: Clarina Howard Nichols and the Politics of Motherhood Marilyn Blackwell 2010. Find in a Maine Library Clarina Irene Howard Nichols was a journalist, lobbyist and public speaker involved in all three of the major reform movements of the mid-19th century: temperance, abolition, and the women's movement that emerged largely out of the ranks of the first two. Mr. President, How Long Must We Wait: Alice Paul, Woodrow Wilson, and the Fight for the Right to Vote, Tina Cassidy 2019 Find in a Maine Library The author of Jackie After 0 examines the complex relationship between suffragist leader Alice Paul and President Woodrow Wilson, revealing the life-risking measures that Paul and her supporters endured to gain voting rights for American women. -

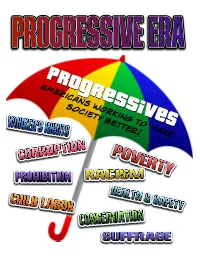

Americans Working to Make Society Better!

Americans working to make society better! New York City The rise of immigration brought millions Slums of people into overcrowded cities like New York City and Chicago. Many families could not afford to buy houses and usually lived in rented apartments or Crowded Tenements. These buildings were run down and overcrowded. These families had few places to turn to for help. Often times, tenements were poorly designed, unsafe, and lacked running water, electricity, and sanitation. Entire neighborhoods of tenement buildings became urban slums. Hull House, Chicago Jacob A Riis was a photographer whose photos of slums and tenements in New York City shocked society. His photography exposed the poor conditions of the lower class to the wealthier citizens and inspired many people to join in Jane Addams efforts to reform laws and improve living conditions in the slums. Jacob A. Riis Jane Addams helped people in a neighborhood of immigrants in Chicago, Illinois. She and her friend, Ellen Starr, bought a house and turned it into a Settlement House to provide services for poor people in the community. Addams' settlement house was called Hull House and it, along with other settlement houses established in other urban areas, offered opportunities such as english classes, child care, and work training to community residents. Large businesses were growing even larger. The rich and powerful wanted to continue their individual success and maintain their power. The federal and local governments became increasingly corrupt. Elected officials would often bribe people for support. Political Machines were organizations that influenced votes and controlled local governments. Politicians would break rules to win elections. -

Diamond, Pearl, Golden and Silver Soror

Diamond, Pearl, Golden and Silver Soror Virtual Celebration Souvenir Keepsake Program CELEBRATING EXCELLENCE IN SISTERHOOD AND SERVICE Honoring Our 2019 and 2020 Milestone Sorors Sunday, January 10, 2021 2p.m. CST YEARS OF RECOGNITION FOR DPGS HONOREES Diamond Sorors initiated in Golden Sorors initiated in 1944 or 1945 1969 or 1970 Inaugural Pearl Sorors initiated in Silver Sorors initiated in 1946, 1947, 1948, 1949, 1950, 1951, 1952, 1953, 1994 or 1995 1954 or 1955 Th is virtual celebration will be streamed live on the offi cial Alpha Kappa Alpha Facebook page and YouTube channel. Soror Glenda Glover Supreme Basileus Directorate Glenda Glover Supreme Basileus Danette Anthony Jasmyne E. McCoy Chelle Luper Gayle P. Bonnie Alysse Guerrier Jasmine Williams Reed Second Supreme Wilson Miles-Scott Washington Undergraduate Undergraduate First Supreme Anti-Basileus Supreme Supreme Murdah Member-At-Large Member-At-Large Anti-Basileus Grammateus Tamiouchos Supreme Parliamentarian Mary Bentley Jennifer King Carolyn G. Carrie J. Clark Mitzi Dease Paige Joya T. Hayes Sonya L. Bowen LaMar Congleton Randolph Great Lakes South Eastern South Central Central North Atlantic Mid-Atlantic South Atlantic Regional Director Regional Director Regional Director Regional Director Regional Director Regional Director Regional Director Twyla G. Woods- Shelby D. Boagni Joy Elaine Daley Buford Far Western International Mid-Western Regional Director Regional Director Regional Director 2 Diamond/Pearl/Golden/Silver Sorors Committee Tamara Cubit Angela C. Gibson Sharon Brown Lenora Ivy South Central North Atlantic Harriott Mid-Western South Atlantic Alana M. Broady Chairman Central Patrice Washington Renee Reed Micou Sharon Ella Turner-Gray Langford Great Lakes Shaw-McEwen Far Western South Central South Eastern Membership Committee Arla J.