The Implications of Racial Context to the Canadian Provocation Defense, 35 U

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1960 Surname

Surname Given Age Date Page Maiden Note Abbett Marda R. 25-Jan A-11 Abel Maude 53 4-Apr B-3 Abercrombie Julia 63 8-Nov A-11 Acheson Robert Worth 63 23-Aug B-3 Acker Ella 88 28-Mar B-3 Adamchuk Steve 65 30-Aug A-11 Adamek Anna 86 4-Sep B-3 Adams Helen B. 49 15-Jul B-3 Adams Homer Taylor 75 21-Mar B-3 Addlesberger Frank H. 62 14-Jun B-3 Adelsperger Carolina C. (Carrie)_ 69 18-Nov B-3 Adlers Nellie C.. 43 14-Feb B-3 Aguilar Juan O., Jr. 19 24-Feb 1 Ahedo Lupe 62 17-Aug B-3 Ahlendorf Alvina L. 74 4-Aug B-3 Ahrendt Martha 70 28-Dec B-3 Ainsworth Alta Belle 76 28-Jul A-11 Albertsen Rosella 61 22-Feb A-11 Alexander Ernest R. 83 14-Nov B-3 Alexander Joseph H. 82 15-Jul B-3 Allande Emil 54 17-Jun B-3 Allen William 14-Jun B-3 Alley Margaret B. 53 18-Jan A-11 Almanzia Maria 72 3-Oct B-3 Alvarado Ruby 49 11-Jan A-11 Alvey Wylie G. 80 19-Sep A-11 Ambre Henry L. 85 7-Nov B-5 Ambrose Paul R. 2 26-May 1 Andel Michael, Sr. 69 14-Sep B-3 Andersen Neils P. 74 13-Jun B-3 Anderson Daniel 2 19-Jan A-9 Anderson Donald R. 47 3-Jul B-3 Anderson Irene 59 4-Dec B-3 Anderson Jessie (Rohde) 66 18-Jan A-11 Anderson John B. -

INDEX to 1915-1919 Obituaries in the Canton Repository

INDEX To 1915-1919 Obituaries in the Canton Repository Published by the Stark County District Library of Canton, Ohio 2005 Index to 1915-1919 Obituaries in the Canton Repository The following is an alphabetical listing, by the deceased’s surname, of obituaries that appeared in the Canton, Ohio newspaper, The Repository. It was compiled by the library staff during the course of the year in the hope that it would be a useful tool to genealogy, as well as other researchers. To use this index, simply locate the name of the person whose obituary you wish to find. The entries will appear as follows: Miller William A. (Estella M.) Mrs. 1924 Jan. 13 30 The first column is the name of the deceased. The second gives the date on which the item appeared. And the third tells the page number containing the obituary. You may find one name with multiple listings showing different dates and locations in the paper. This indicates consecutive listings for that individual. I encourage you to view each for additional information. Index to 1915-1919 Obituaries in the Canton Repository Surname Given Name Maiden Title Year Mth Day Pg ? Mary 1918 Apr. 18 15 Aaron Benjamin 1918 Nov. 27 2 Abbott Lawrence C. 1919 Mar. 14 24 Abels infant 1919 July 16 6 Abherve Minnie Jacobs Mrs. 1918 Dec. 13 33 Abrams Leo 1917 Apr. 24 2 Abt Leo 1918 Apr. 27 1 Abvrezis Macone 1917 Sept. 17 2 Acker L. E. 1918 Jan. 13 26 Acker Leonard E. 1918 Jan. 12 5 Acker Sarah Mrs. -

16Th FINA World Masters Championships 2015 KAZAN (RUS)

16th FINA World Masters Championships 2015 KAZAN (RUS) 800 m Freestyle Men Results RANK SURNAME & NAME FED BORN 50 m 100 m 200 m 300 m 400 m 500 m 600 m 700 m FINAL TEAM CAT AGE GROUP 85-89 QUALIFYING STANDARD: 23:13.00 CR : 15:16.96 WR : 14:37.00 1 SKOBELEV Boris RUS 1930 57.07 2:04.20 4:21.07 6:40.73 8:59.42 11:19.63 13:41.02 16:02.54 18:20.43 Russian Reserve 85-89 1:07.13 2:16.87 2:19.66 2:18.69 2:20.21 2:21.39 2:21.52 2:17.89 2 COUTTIE Peter AUS 1930 1:10.96 2:34.81 5:22.83 8:08.13 10:53.13 13:37.70 16:20.90 19:02.42 21:41.08 Malvern Marlins 85-89 1:23.85 2:48.02 2:45.30 2:45.00 2:44.57 2:43.20 2:41.52 2:38.66 AGE GROUP 80-84 QUALIFYING STANDARD: 20:40.00 CR : 13:28.82 WR : 11:49.00 1 VERESHAGINE Anry RUS 1934 43.97 1:30.97 3:10.65 4:51.02 6:33.13 8:15.05 9:57.37 11:39.31 13:15.13 CR All Stars 80-84 47.00 1:39.68 1:40.37 1:42.11 1:41.92 1:42.32 1:41.94 1:35.82 2 BROVIN Igor RUS 1932 44.99 1:36.71 3:26.25 5:15.64 7:07.53 8:58.81 10:53.14 12:52.05 14:39.25 Sprut 80-84 51.72 1:49.54 1:49.39 1:51.89 1:51.28 1:54.33 1:58.91 1:47.20 3 MULLINS Steve USA 1932 56.13 2:04.19 4:18.97 6:35.14 8:50.62 11:04.23 13:18.27 15:29.71 17:32.64 Illinois Masters 80-84 1:08.06 2:14.78 2:16.17 2:15.48 2:13.61 2:14.04 2:11.44 2:02.93 4 KAMAL Ahmed Fouad EGY 1933 54.26 2:00.61 4:23.06 6:43.94 9:06.08 11:27.77 13:45.86 16:04.98 18:07.97 Gezira Sporting Club 80-84 1:06.35 2:22.45 2:20.88 2:22.14 2:21.69 2:18.09 2:19.12 2:02.99 NOT CLASSIFIED 0 HOLE Gerhard GER 1935 80-84 Ssf Bonn 05 DNS AGE GROUP 75-79 QUALIFYING STANDARD: 18:50.00 CR : 11:25.95 WR : 11:08.00 -

Muslims in Spain, 1492–1814 Mediterranean Reconfigurations Intercultural Trade, Commercial Litigation, and Legal Pluralism

Muslims in Spain, 1492– 1814 Mediterranean Reconfigurations Intercultural Trade, Commercial Litigation, and Legal Pluralism Series Editors Wolfgang Kaiser (Université Paris I, Panthéon- Sorbonne) Guillaume Calafat (Université Paris I, Panthéon- Sorbonne) volume 3 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ cmed Muslims in Spain, 1492– 1814 Living and Negotiating in the Land of the Infidel By Eloy Martín Corrales Translated by Consuelo López- Morillas LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: “El embajador de Marruecos” (Catalog Number: G002789) Museo del Prado. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Martín Corrales, E. (Eloy), author. | Lopez-Morillas, Consuelo, translator. Title: Muslims in Spain, 1492-1814 : living and negotiating in the land of the infidel / by Eloy Martín-Corrales ; translated by Consuelo López-Morillas. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2021] | Series: Mediterranean reconfigurations ; volume 3 | Original title unknown. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020046144 (print) | LCCN 2020046145 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004381476 (hardback) | ISBN 9789004443761 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Muslims—Spain—History. | Spain—Ethnic relations—History. -

Conselleria De Sanitat Consellería De Sanidad

Conselleria de Sanitat Consellería de Sanidad Notificació de liquidacions per taxes sanitàries en Notificación de liquidaciones por tasas sanitarias en l’Hospital General de Castelló. Liquidació número el Hospital General de Castellón. Liquidación número 0466705600514 i altres. [2014/517] 0466705600514 y otras. [2014/517] Segons que disposa l’article 112 de la Llei 58/2003, de 17 de De conformidad con lo dispuesto en el artículo 112 de la Ley desembre, General Tributària, i com que s’ha intentat la notificació a la 58/2003, de 17 de diciembre, General Tributaria, y habiéndose intenta- persona interessada o al seu representant per dues vegades, sense que do la notificación al interesado o su representante por dos veces, sin que haja sigut possible per causes no imputables al centre gestor, es posa haya sido posible practicarlas por causas no imputables al centro gestor, de manifest, mitjançant este anunci, que estan pendents de notificar les se pone de manifiesto, mediante el presente anuncio, que se encuentran liquidacions per taxes sanitàries que s’especifiquen a continuació. pendientes de notificar las liquidaciones por tasas sanitarias cuyo inte- resado se especifica a continuación. Per tot això, dispose que els subjectes passius, obligats tributaris En virtud de lo anterior dispongo que los sujetos pasivos, obligados indicats anteriorment, o els seus representants ben acreditats, hauran de tributarios indicados anteriormente, o sus representantes debidamente comparéixer en el termini de 15 dies naturals, comptadors des de l’ende- acreditados, deberán comparecer en el plazo de 15 días naturales, con- mà de la publicació d’esta resolució en el Diari Oficial de la Comunitat tados desde el siguiente al de la publicación de la presente resolución Valenciana, de dilluns a divendres, en l’horari de 09.00 a 14.00 hores, en el Diari Oficial de la Generalitat Valenciana, de lunes a viernes, en en el centre gestor Hospital de Castelló (av. -

Surname First Name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen

2018 DRIVERS' CATEGORISATION LIST Updated on 09/07/2018 Drivers in red : revised categorisation Drivers in blue : new categorisation Surname First name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen Klaus Bronze Abbott Hunter Silver Abbott James Silver Abe Kenji Bronze Abelli Julien Silver Abergel Gabriele Bronze Abkhazava Shota Bronze Abra Richard Silver Abreu Attila Gold Abril Vincent Gold Abt Christian Silver Abt Daniel Gold Accary Thomas Silver Acosta Hinojosa Julio Sebastian Silver Adam Jonathan Platinum Adams Rudi Bronze Adorf Dirk Silver Aeberhard Juerg Silver Afanasiev Sergei Silver Agostini Riccardo Gold Aguas Rui Gold Ahlin-Kottulinsky Mikaela Silver Ahrabian Darius Bronze Ajlani Karim Bronze Akata Emin Bronze Aksenov Stanislas Silver Al Faisal Abdulaziz Silver Al Harthy Ahmad Silver Al Masaood Humaid Bronze Al Qubaisi Khaled Bronze Al-Azhari Karim Bronze Alberico Neil Silver Albers Christijan Platinum Albert Michael Silver Albuquerque Filipe Platinum Alder Brian Silver Aleshin Mikhail Platinum Alesi Giuliano Silver Alessi Diego Silver Alexander Iradj Silver Alfaisal Saud Bronze Alguersuari Jaime Platinum Allegretta Vincent Silver Alleman Cyndie Silver Allemann Daniel Bronze Allen James Silver Allgàuer Egon Bronze Allison Austin Bronze Allmendinger AJ Gold Allos Manhal Bronze Almehairi Saeed Silver Almond Michael Silver Almudhaf Khaled Bronze Alon Robert Silver Alonso Fernando Platinum Altenburg Jeff Bronze Altevogt Peter Bronze Al-Thani Abdulrahman Silver Altoè Giacomo Silver Aluko Kolawole Bronze Alvarez Juan Cruz Silver Alzen -

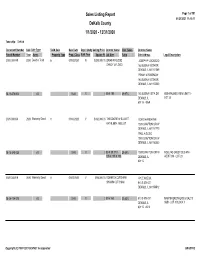

Ao-Sales-Dekalb2020.Pdf

Sales Listing Report Page 1 of 191 01/21/2021 11:10:11 DeKalb County 1/1/2020 - 12/31/2020 Township: DeKalb Document Number Sale Sale Type Valid Sale Sale Date Dept. Study Selling Price Grantor Name Curr. Sales Grantee Name Parcel Number Year Acres Property Type Prop. Class Built Year Square Ft. Lot Size Ratio Site Address Legal Description 2020-000145 2020 Deed in Trust N 01/03/2020 N $325,000.00 BRIAN R FLOOD JOSEPH P LOCASCIO SANDY L FLOOD 163 BUENA VISTA DR DEKALB, IL 601151069 PENNY A ROSENOW 163 BUENA VISTA DR DEKALB, IL 601150000 08-11-478-006 .00 0040 0 0 90 X 180 29.97% 163 BUENA VISTA DR KISHWAUKEE VIEW UNIT 3 - DEKALB, IL LOT 23 60115 -1069 2020-000166 2020 Warranty Deed Y 01/03/2020 Y $182,000.00 THEODORE W ELLIOTT ELVI S HANDAYANI KATHLEEN J ELLIOT 1509 CRAYTON CIR W DEKALB, IL 601151770 PAUL A GOGO 1509 CRAYTON CIR W DEKALB, IL 601150000 08-15-248-028 .00 0040 0 0 80 X 39.27 X 29.69% 1509 CRAYTON CIR W ROLLING CREST SUB 4TH 105 X 105 X 130 DEKALB, IL ADDITION - LOT 28 60115 2020-000219 2020 Warranty Deed Y 01/07/2020 Y $94,000.00 ROBERTA CUTSHAW KYLE KOZIOL SHAWN CUTSHAW 913 S 5TH ST DEKALB, IL 601154512 08-26-104-010 .00 0040 0 0 50 x 169 33.62% 913 S 5TH ST MARTIN BROTHERS & GALTS DEKALB, IL SUB - LOT 3 BLOCK 1 60115 -4512 Copyright (C) 1997-2021 DEVNET Incorporated BRADTKE Sales Listing Report Page 2 of 191 01/21/2021 11:10:11 DeKalb County 1/1/2020 - 12/31/2020 Township: DeKalb Document Number Sale Sale Type Valid Sale Sale Date Dept. -

Obituary Index-F Surnames

Name Year Month Day Age Page Newspaper Date Source Note FAATZ, PATRICIA A 2020 5 14 78 05/16/2020 LANC NEWSPAPERS NO OBIT PUBLISHED FABER, CYNTHIA J 2007 6 27 67 0 06/30/2007 LANC NEWSPAPERS FABER, NANCY H FERBER 2016 3 10 89 03/11/2016 LANC NEWSPAPERS FABER, RICHARD J JR 2017 2 27 91 03/01/2017 LANC NEWSPAPERS FABER, ROBERT PETER 1994 1 25 25 54 SCRAPBOOK FABIAN, CAROLYN S 1998 1 24 50 42 SCRAPBOOK FABIAN, ESTELLE GRACE 2015 6 3 65 06/09/2015 LANC NEWSPAPERS FABIAN, JERRY C 2001 7 5 46 310 SCRAPBOOK FABIAN, ROBERT J 2005 10 9 78 0 10/11/2005 LANC NEWSPAPERS FABIAN, STEVE A 2005 2 21 56 78 SCRAPBOOK FABIAN, TERRY A 2000 6 27 45 349 SCRAPBOOK FABIAN, WALTER A 1971 82 297 07/22/1971 CB OBITS FABIAN, WALTER A SR 1971 7 17 82 128 SCRAPBOOK FABIANI, FRANK J 2020 4 21 64 04/22/2020 LANC NEWSPAPERS NO OBIT PUBLISHED FABIANSKI, THEODORE KASIMIR 2003 12 13 80 499 SCRAPBOOK FABLE, RITA FROHOCK 2004 8 17 78 355 SCRAPBOOK FABRE, JANE M (NIGHTENGALE) 2013 7 26 84 07/29/2013 INTELLIGENCER JOURNAL FABRE, JOHN S 1990 12 22 81 509 SCRAPBOOK FABRIZIO, JOSEPH D 2002 10 16 69 453 SCRAPBOOK FABRIZIO, JOSEPH P SR 2007 5 9 84 0 05/11/2007 LANC NEWSPAPERS FABRIZIO, MAE E 2015 11 14 90 11/17/2015 LANC NEWSPAPERS FACEMIRE, H WAYNE 1989 5 25 33 167 SCRAPBOOK FACENDOLA, STEVEN G 2017 8 11 31 08/15/2017 LANC NEWSPAPERS FACEY, MARYANN 2000 4 20 66 230 SCRAPBOOK FACKENTHAL, FRANK D DR 1968 9 5 85 11 SCRAPBOOK FACKLER, ALBERT R 2012 10 7 79 10/09/2012 LANC NEWSPAPERS FACKLER, ANNA C 1984 11 3 72 250 SCRAPBOOK FACKLER, ANNIE K 1949 2 28 73 179 AKS OBIT BK 1 FACKLER, ARLENE -

PETITION List 04-30-13 Columns

PETITION TO FREE LYNNE STEWART: SAVE HER LIFE – RELEASE HER NOW! • 1 Signatories as of 04/30/13 Arian A., Brooklyn, New York Ilana Abramovitch, Brooklyn, New York Clare A., Redondo Beach, California Alexis Abrams, Los Angeles, California K. A., Mexico Danielle Abrams, Ann Arbor, Michigan Kassim S. A., Malaysia Danielle Abrams, Brooklyn, New York N. A., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Geoffrey Abrams, New York, New York Tristan A., Fort Mill, South Carolina Nicholas Abramson, Shady, New York Cory a'Ghobhainn, Los Angeles, California Elizabeth Abrantes, Cambridge, Canada Tajwar Aamir, Lawrenceville, New Jersey Alberto P. Abreus, Cliffside Park, New Jersey Rashid Abass, Malabar, Port Elizabeth, South Salma Abu Ayyash, Boston, Massachusetts Africa Cheryle Abul-Husn, Crown Point, Indiana Jamshed Abbas, Vancouver, Canada Fadia Abulhajj, Minneapolis, Minnesota Mansoor Abbas, Southington, Connecticut Janne Abullarade, Seattle, Washington Andrew Abbey, Pleasanton, California Maher Abunamous, North Bergen, New Jersey Andrea Abbott, Oceanport, New Jersey Meredith Aby, Minneapolis, Minnesota Laura Abbott, Woodstock, New York Alexander Ace, New York, New York Asad Abdallah, Houston, Texas Leela Acharya, Toronto, Canada Samiha Abdeldjebar, Corsham, United Kingdom Dennis Acker, Los Angeles, California Mohammad Abdelhadi, North Bergen, New Jersey Judith Ackerman, New York, New York Abdifatah Abdi, Minneapolis, Minnesota Marilyn Ackerman, Brooklyn, New York Hamdiya Fatimah Abdul-Aleem, Charlotte, North Eddie Acosta, Silver Spring, Maryland Carolina Maria Acosta, -

Using Standard Syste

PHYSICAL REVIEW D VOLUME 55, NUMBER 10 15 MAY 1997 Cumulative Author Index All authors of papers published so far in the current volume are listed alphabetically with the issue and page numbers following the dash. A more complete index, with the full title listed with each ®rst author's name and subsequent authors cross-referenced, is published in the last issue of the volume. A cumulative author and subject index covering Physical Review A through E, Physical Review Letters, and Reviews of Modern Physics is published annually under separate cover. Abashian, A.Ð͑9͒ 5667 Anderson, Paul R.Ð͑6͒ 3440; ͑10͒ 6116 Badgett, W.Ð͑3͒ 1142; ͑5͒ 2546; Abbasabadi, AliÐ͑9͒ 5647 Anderson, S.Ð͑3͒ R1119; ͑5͒ 2559; ͑9͒ R5263 Abe, F.Ð͑3͒ 1142; ͑5͒ 2546; ͑9͒ R5263 ͑7͒ R3919; ͑9͒ 5273 Baer, HowardÐ͑3͒ 1466; ͑5͒ 3201; Abe, K.Ð͑1͒ 19; ͑5͒ 2533, 2533 Andersson, NilsÐ͑2͒ 468 ͑7͒ 4463 Andreev, Yu. M.Ð͑3͒ 1233 Abel, S. A.Ð͑3͒ 1623 Bagdasarov, S.Ð͑3͒ 1142; ͑5͒ 2546; Anisovich, V. V.Ð͑5͒ 2918 Abney, MarkÐ͑2͒ 582 ͑9͒ R5263 Anninos, PeterÐ͑2͒ 829; ͑4͒ 1948 Abrahams, AndrewÐ͑2͒ 829 Bagger, JonathanÐ͑2͒ 1091 Anselmino, M.Ð͑9͒ 5841 Abt, I.Ð͑5͒ 2533 ͑ ͒ AntilloÂn, ArmandoÐ͑10͒ 6327 Bagger, Jonathan A.Ð 5 3188 Acharya, B. S.Ð͑8͒ R4521 Antoniadis, IgnatiosÐ͑8͒ 4756, 4770 Baier, R.Ð͑7͒ 4344 Achasov, N. N.Ð͑5͒ 2663, 2672 Antoniazzi, L.Ð͑7͒ 3927 Bailey, M. W.Ð͑3͒ 1142; ͑5͒ 2546; Adam, ChristophÐ͑10͒ 6299 Antos, J.Ð͑3͒ 1142; ͑5͒ 2546; ͑9͒ R5263 ͑9͒ R5263 Adhikari, RathinÐ͑6͒ 3836 Antunes, Nuno D.Ð͑2͒ 925 Baird, K. G.Ð͑5͒ 2533 Afanasev, AndreiÐ͑7͒ 4380 Anway-Wiese, C.Ð͑3͒ 1142; ͑5͒ 2546 Baker, JohnÐ͑2͒ 829 Ahlen, S. -

Index to 2003 Obituaries in the Canton Repository

Index to 2003 Obituaries in the Canton Repository Published by the Stark County District Library Canton, Ohio 2005 Page 1 Index to 2003 Obituaries in the Canton Repository The following is an alphabetical listing, by the deceased’s surname, of obituaries that appeared in the Canton, Ohio newspaper, The Repository. It was compiled by the library staff during the course of the year in the hope that it would be a useful tool to genealogy, as well as other researchers. To use this index, simply locate the name of the person whose obituary you wish to find. The entries will appear as follows: Miller William A. (Estella M.) Mrs. 1940 Jan. 13 30 The first column is the name of the deceased. The second gives the date on which the item appeared. And the third tells the page number containing the obituary. You may find one name with multiple listings showing different dates and locations in the paper. This indicates consecutive listings for that individual. I encourage you to view each for additional information. Page 2 Index to Obituaries in the 2003 Canton Repository Surname Given Name Maiden Title Year Mth. Day Sec. Pg. Abate Tammy Lynn Taylor 2003 Jan. 28 B 4 Abate Tammy Lynn Taylor 2003 Jan. 28 B 5 Abrams Harlan 2003 Apr. 27 B 4 Acker Mary Ann 2003 Jan. 11 B 3 Ackeret Vernon C. 2003 May 26 B 6 Ackerman Donald E. 2003 May 10 B 4 Ackerman Geraldine M. Kintz 2003 Feb. 19 B 4 Ackerman Jack J. 2003 May 30 B 4 Ackerman Marilyn S. -

Surname Given Maiden Name Date Page Adams Floyd, O. 20-Feb-48 43 Adams John, Myron 30-May-48 46 Adley Joseph, A

Surname Given Maiden Name Date Page Adams Floyd, O. 20-Feb-48 43 Adams John, Myron 30-May-48 46 Adley Joseph, A. 26-May-48 64 Agles Carolyn Foust 23-Dec-48 50 Alcantar Nellie 19-Nov-48 28 Alger William Henry 23-Feb-48 87 Allen Francis 8-Apr-48 72 Allen Louise 2-Feb-48 76 Almason Catherine May l8, 1948 69 Almay Edward 20-Dec-48 54 Alsman Marion, E. 24-Oct-48 44 Alt Henry, C. April ll, 1948 66 Alvarez Ferdinand, J. (S/Sgt.) December 2l, 1948 25 Alyea William November l5, 1948 77 Ambrus John D. (Pfc.) August l7, 1948 26 Amrai Katherine November l0, 1948 78 Ancich John 27-May-48 65 Anderson Arvid Carl III 23-Aug-48 6 weeks Anderson Bertie Marie 5-Sep-48 2 months Anderson George (Tech/Sgt.) December l6, 1948 29 Anderson John March 2l, 1948 66 Andreotti Peter (2nd Lt.) 28-Jun-48 24 Androff Thomas Carl 24-Oct-48 3 Anest Harry 29-Aug-48 67 Angelcoff George March l5, 1948 46 Angelich Emil February l6, 1948 58 Antonowicz Joseph, J. 9-May-48 70 Aponiak Alex 6-Jan-48 68 Armstrong Myrtle 22-Mar-48 66 Armstrong Walter, S. March l0, 1948 51 Arsulich Thomas 23-Nov-48 77 Augustyn Louis Septermber l9, 1948 57 Ault Lulu 30-Nov-48 75 Austgen Lillian 2-May-48 68 Austgen Mary 22-Jun-48 66 Baars William 6-Jan-48 83 Babbitt Nellie 4-May-48 76 Babe Henry, O. 23-Feb-48 58 Babic John 26-Jan-48 58 Babicz Louis 29-Jul-48 60 Babincsak Elizabeth 29-Aug-48 81 Babinscak Michael 7-Jun-48 64 Babyak Michael 27-Feb-48 58 Bacan Nick August l6, 1948 53 Baert Jennie 30-Aug-48 74 Bagamery James 8-Dec-48 69 Bailey Maude November l, 1948 66 Baker Gertrude Ausugst 25, 1948 86 Baker Ima December l5, 1948 46 Baker Lloyd Ira 7-Dec-48 63 Balczo James 23-Nov-48 5 months Baliga Mathew July l9, 1948 53 Ballon Albert, J.