Convergent Winds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: a Study of Traditions and Influences

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2012 Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences Sara Gardner Birnbaum University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Birnbaum, Sara Gardner, "Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 7. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/7 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series Frank Morelli, Bassoon Behind every Juilliard artist is all of Juilliard —including you. With hundreds of dance, drama, and music performances, Juilliard is a wonderful place. When you join one of our membership programs, you become a part of this singular and celebrated community. by Claudio Papapietro Photo of cellist Khari Joyner Photo by Claudio Papapietro Become a member for as little as $250 Join with a gift starting at $1,250 and and receive exclusive benefits, including enjoy VIP privileges, including • Advance access to tickets through • All Association benefits Member Presales • Concierge ticket service by telephone • 50% discount on ticket purchases and email • Invitations to special • Invitations to behind-the-scenes events members-only gatherings • Access to master classes, performance previews, and rehearsal observations (212) 799-5000, ext. 303 [email protected] juilliard.edu The Juilliard School presents Faculty Recital: Frank Morelli, Bassoon Jesse Brault, Conductor Jonathan Feldman, Piano Jacob Wellman, Bassoon Wednesday, January 17, 2018, 7:30pm Paul Hall Part of the Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series GIOACHINO From The Barber of Seville (1816) ROSSINI (arr. François-René Gebauer/Frank Morelli) (1792–1868) All’idea di quell metallo Numero quindici a mano manca Largo al factotum Frank Morelli and Jacob Wellman, Bassoons JOHANNES Sonata for Cello, No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 38 (1862–65) BRAHMS Allegro non troppo (1833–97) Allegro quasi menuetto-Trio Allegro Frank Morelli, Bassoon Jonathan Feldman, Piano Intermission Program continues Major funding for establishing Paul Recital Hall and for continuing access to its series of public programs has been granted by The Bay Foundation and the Josephine Bay Paul and C. -

Unifying Elements of John Corigliano's

UNIFYING ELEMENTS OF JOHN CORIGLIANO'S ETUDE FANTASY By JANINA KUZMAS Undergraduate Diploma with honors, Sumgait College of Music, USSR, 1985 B. Mus., with the highest honors, Vilnius Conservatory, Lithuania, 1991 Performance Certificate, Lithuanian Academy of Music, 1993 M. Mus., Bowling Green State University, USA, 1995 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES School of Music We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February 2002 © Janina Kuzmas 2002 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. ~':<c It CC L Department of III -! ' The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date J/difc-L DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT John Corigliano's Etude Fantasy (1976) is a significant and challenging addition to the late twentieth century piano repertoire. A large-scale work, it occupies a particularly important place in the composer's output of music for piano. The remarkable variety of genres, styles, forms, and techniques in Corigliano's oeuvre as a whole is also evident in his piano music. -

The English Oboe: Rediscovered 4 AEGEUS (1996) 8’21 THOMAS ATTWOOD WALMISLEY (1814-1856) SONATINA NO

EDMUND RUBBRA (1901-1986) SONATA IN C FOR OBOE AND PIANO, OP. 100 1 Con moto 5’49 2 Elegy 4’15 3 Presto 3’30 EDWARD LONGSTAFF (1965- ) The English Oboe: Rediscovered 4 AEGEUS (1996) 8’21 THOMAS ATTWOOD WALMISLEY (1814-1856) SONATINA NO. 1 JAMES TURNBULL oboe 5 Andante mosso - Allegro moderato 8’49 JOHN CASKEN (1949- ) 6 AMETHYST DECEIVER FOR SOLO OBOE (2009) 7’16 (World premiere recording) GUSTAV HOLST (1874-1934) TERZETTO FOR FLUTE, OBOE AND VIOLA 7 Allegretto 6’59 8 Un poco vivace 4’36 MICHAEL BERKELEY (1948- ) THREE MOODS FOR UNACCOMPANIED OBOE 9 Very free. Moderato 5’24 10 Fairly free. Andante 2’33 11 Giocoso 2’13 RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872-1958) SIX STUDIES IN ENGLISH FOLKSONG FOR COR ANGLAIS AND PIANO 12 Adagio 1’37 13 Andante sostenuto 1’28 14 Larghetto 1’31 15 Lento 1’36 16 Andante tranquillo 1’33 17 Allegro vivace 0’54 Total playing time: 68’34 James Turnbull ~ oboe / cor anglais (all tracks) Libby Burgess ~ piano (tracks 1-5 and 12-17) Matthew Featherstone ~ flute (tracks 7-8) Dan Shilladay ~ viola (tracks 7-8) FOREWORD PROGRAMME NOTES For a long time, I have been drawn towards English oboe music. It was therefore a Edmund Rubbra wrote much chamber music, including pieces for almost every straightforward decision to choose this repertoire to record. My aim was to introduce the instrument. He composed his Sonata for Oboe and Piano, op. 100, in 1958 for most varied programme possible: as a result, this disc spans over a century. -

Production Database Updated As of 25Nov2020

American Composers Orchestra Works Performed Workshopped from 1977-2020 firstname middlename lastname Date eventype venue work title suffix premiere commission year written Michael Abene 4/25/04 Concert LGCH Improv ACO 2004 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Piano Improv Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Violin & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Double Bass & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/9/00 Concert CH Tomorrow's Song, as Yesterday Sings Today World 2000 Ricardo Lorenz Abreu 12/4/94 Concert CH Concierto para orquesta U.S. 1900 John Adams 4/25/83 Concert TULLY Shaker Loops World 1978 John Adams 1/11/87 Concert CH Chairman Dances, The New York ACO-Goelet 1985 John Adams 1/28/90 Concert CH Short Ride in a Fast Machine Albany Symphony 1986 John Adams 12/5/93 Concert CH El Dorado New York Fromm 1991 John Adams 5/17/94 Concert CH Tromba Lontana strings; 3 perc; hp; 2hn; 2tbn; saxophone1900 quartet John Adams 10/8/03 Concert CH Christian Zeal and Activity ACO 1973 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH The Wound-Dresser 1988 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH My Father Knew Charles Ives ACO 2003 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH Violin Concerto 1993 John Luther Adams 10/15/10 Concert ZANKL The Light Within World 2010 Victor Adan 10/16/11 Concert MILLR Tractus World 0 Judah Adashi 10/23/15 Concert ZANKL Sestina World 2015 Julia Adolphe 6/3/14 Reading FISHE Dark Sand, Sifting Light 2014 Kati Agocs 2/20/09 Concert ZANKL Pearls World 2008 Kati Agocs 2/22/09 Concert IHOUS -

Trumpet Music by Women Composers

Trumpet Music by Women Composers Amy Dunker, DMA Professor of Music Theory, Composition and Trumpet Clarke University 1550 Clarke Drive Dubuque, IA 52001 [email protected] www.amydunker.com If you perform a composer’s work, please email them and/or send them a program. It is important to know that your work is appreciated! Trumpet Alone Beamish, Sally: Fanfare for Solo Trumpet (Trumpet Alone) http://www.warwickmusic.com/Main-Catalogue/Sheet-Music/Trumpet/Solo-Trumpet/Beamish-Fanfare- for-Solo-Trumpet-TR065 Beat, Janet: Fireworks in Steel (Trumpet Alone) http://furore-verlag.de/shop/noten/trompete/ Bernofsky, Lauren: Fantasia (Trumpet Alone) http://laurenbernofsky.com/works.php Bielawa, Lisa: Synopsis No. 5 (Trumpet Alone) http://lisabielawa.typepad.com/works_section/ Bingham, Judith: Enter Ghost Act 1, Scene 3 of Hamlet (Trumpet Alone) http://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/enter-ghost-act-1-scene-3-of-hamlet-2002-sheet-music/19110817 Bouchard, Linda: Propos (Trumpet Alone or Trumpet Ensemble) http://www.musiccentre.ca/node/21128 Campbell, Karen: Pieces (Trumpet Alone) http://library.newmusicusa.org/library/composition.aspx?CompositionID=85460 Clarke, Rosemary: Winter’s Winds (Trumpet Alone) http://library.newmusicusa.org/library/composition.aspx?CompositionID=86228 Cronin, Tanya: Undercurrents (Trumpet Alone) http://library.newmusicusa.org/library/composition.aspx?CompositionID=86700 Dinescu, Violeta: Abendandacht (Trumpet Alone) http://www.composers21.com/compdocs/dinescuv.htm Dunker, Amy: Advanced Solos (Trumpet Alone) 1. "Distant -

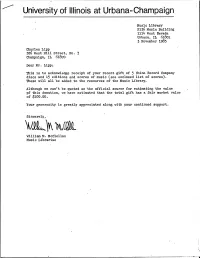

Lipp Donations Lists

-~~--~---·-~--·---·--·~----CO-~·---•o- •••---••-c~--·-~••·------·-----~-". University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Music Library 2136 Music Building 1114 West Nevada Urbana, IL 61801 3 rlovember 1983 Charles Lipp 306 West Hill Street, No. ; Champaign, IL 61820 Dear Mr. Lipp: This is to acknowledge receipt of your recent gift of 5 China Record Company discs and 15 editions and scores of music (see enclosed list of scores). These will all be added to the resources of the Music Library. Although we can't be quoted as the official source for estimating the value pf this donation, we have estimated that the total gift has a fair market value of $100.00. Your generosity is greatly appreciated along with your continued support. Sincerely, \Vlt. ..~ 'M~(®l William M. McClellan Music Librarian \ 1('y-r-.(..~~ ~"7 'S. ~ ~ <liARLES LIPP DONATION November 1, 1983 \ Scores: \ .. ! ''.<',. Andriessen, JurriaaQ Concertina voor fagot en Blazerse~mble. Amsterdam: Donemus, c1962. Study score. Andriessen, Jurriaan , Concertina_ voor fagot en B1azersensemble. Amsterdam: Donemus, c1962. Set of 11 parts. ~· ;;.,._ we 15 Beethoven, Ludwig van .Octet in E flat,. op. 103, for 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 horns, & g bassoons. London: Musica Rara, c1969. Set of 8 parts. · ',t· Dp.kelsky, Vladimir Etude, for violin and bassoon. cl939 by Sprague-Coleman. Fulkerson, James Patterns VII, for any Solo Instrument. cl972 by Fulkerson. Photocopy of MS. Hartzell, Eugene Monologue 3: Divertimento for Basaoon Solo. Wien: Verlag Doblinger, ci966. "' Heiden, Bernhard "Quintet (19'15) for flute, violin, viola, bassoon and contrabass. Score and 5 parts. Photoc-opy of MS. Persichetti, Vincent ?arable for Solo Bassoon. Bryn Mawr, PA: Elkan-Vogel, cl970. -

Elegy for Flute and Piano Sheet Music

Elegy For Flute And Piano Sheet Music Download elegy for flute and piano sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 4 pages partial preview of elegy for flute and piano sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 2575 times and last read at 2021-09-24 07:04:10. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of elegy for flute and piano you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Flute Solo, Piano Accompaniment Ensemble: Musical Ensemble Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Elegy For Flutes Elegy For Flutes sheet music has been read 3565 times. Elegy for flutes arrangement is for Beginning level. The music notes has 5 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 16:54:46. [ Read More ] Elegy Suite Elegy Suite sheet music has been read 3279 times. Elegy suite arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 01:50:49. [ Read More ] Elegy Pastorale Elegy Pastorale sheet music has been read 3334 times. Elegy pastorale arrangement is for Early Intermediate level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 14:40:20. [ Read More ] Symphonic Sketch No 2 Elegy Symphonic Sketch No 2 Elegy sheet music has been read 3235 times. Symphonic sketch no 2 elegy arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 04:39:17. -

2019 CCPA Solo Competition: Approved Repertoire List FLUTE

2019 CCPA Solo Competition: Approved Repertoire List Please submit additional repertoire, including concertante pieces, to both Dr. Andrizzi and to your respective Department Head for consideration before the application deadline. FLUTE Arnold, Malcolm: Concerto for flute and strings, Op. 45 strings Arnold, Malcolm: Concerto No 2, Op. 111 orchestra Bach, Johann Sebastian: Suite in B Minor BWV1067, Orchestra Suite No. 2, strings Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel: Concerto in D Minor Wq. 22, strings Berio, Luciano: Serenata for flute and 14 instruments Bozza, Eugene: Agrestide Op. 44 (1942) orchestra Bernstein, Leonard: Halil, nocturne (1981) strings, percussion Bloch, Ernest: Suite Modale (1957) strings Bloch, Ernest: "TWo Last Poems... maybe" (1958) orchestra Borne, Francois: Fantaisie Brillante on Bizet’s Carmen orchestra Casella, Alfredo: Sicilienne et Burlesque (1914-17) orchestra Chaminade, Cecile: Concertino, Op. 107 (1902) orchestra Chen-Yi: The Golden Flute (1997) orchestra Corigliano, John: Voyage (1971, arr. 1988) strings Corigliano, John: Pied Piper Fantasy (1981) orchestra Devienne, Francois: Concerto No. 7 in E Minor, orchestra Devienne, Francois: Concerto No. 10 in D Major, orchestra Devienne, Francois: Concerto in D Major, orchestra Doppler, Franz: Hungarian Pastoral Fantasy, Op. 26, orchestra Feld, Heinrich: Fantaisie Concertante (1980) strings, percussion Foss, Lucas: Renaissance Concerto (1985) orchestra Godard, Benjamin: Suite Op. 116; Allegretto, Idylle, Valse (1889) orchestra Haydn, Joseph: Concerto in D Major, H. VII f, D1 Hindemith, Paul: Piece for flute and strings (1932) Hoover, Katherine: Medieval Suite (1983) orchestra Hovhaness, Alan: Elibris (name of the DaWn God of Urardu) Op. 50, (1944) Hue, Georges: Fantaisie (1913) orchestra Ibert, Jaques: Concerto (1933) orchestra Jacob, Gordon: Concerto No. -

Solo Oboe, English Horn with Band

A Nieweg Chart Solo Oboe or Solo English Horn with Band or Wind Ensemble 95 editions April 2017 The 2017 Chart is an update of the 2010 Chart. It is not a complete list of all available works for Oboe or EH and band. Works with prices listed are for sale from any music dealer. Prices current as of 2010. Look at the publisher’s website for the current prices. Works marked rental must be hired directly from the publisher listed. Sample Band Instrumentation code: 3fl[1.2.3/pic] 2ob 7cl[Eb.1.2.3.acl.bcl.cbcl] 3bn[1.2.cbn] 4sax[a.a.t.b] — 4hn 3tp 3tbn euph tuba double bass — tmp+3perc — hp, pf, cel This listing gives the number of parts used in the composition, not the number of players. ------------------ Abbado, Marcello (b. Milan, 1926; ) Concerto in C minor (complete) Arranger / Editor: Trans. Charles T. Yeago Instrumentation: Oboe solo and band Pub: BAS Publishing. SOS-217 http://www.baspublishing.com ------------------ ALBINONI, Tommaso (1674-1745) Concerto in F for TWO Oboes and Band Adapted: Paul R. Brink Grade Level: Medium Pub: Bas Publishing Co.; Score and band set SOS-226 -$65.00 | 2 oboes and piano ENS-708. $10.00 ------------------ ARENZ, Heinz (b. 1924) German wind director, administrator, and composer Concertino fur Solo Oboe und Blasorchester Dur: 7'39" Grade Level: solo 6, band 5 Pub: HeBu Music Publishing; Band score and set 113.00 € Oboe and Piano 11.00 € ------------------ ATEHORTUA, Blas Emilio (b. Medellin, Columbia, 3 October 1933) Concerto for Oboe and Wind Symphony Orchestra Instrumentation listed <http://www.edition-peters.com/pdf/Albinoni-Grieg.pdf> Dur: 15' Pub: C. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313 761-4700 800 521-0600 Order Number 9401192 A selected bibliography of music for clarinet and one other instrument by women composers Richards, Melanie Ann, D.M.A. The Ohio State University, 1993 UMI 300 N. -

Elegy for Piano Cello and Oboe Sheet Music

Elegy For Piano Cello And Oboe Sheet Music Download elegy for piano cello and oboe sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 5 pages partial preview of elegy for piano cello and oboe sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 2520 times and last read at 2021-09-27 16:38:08. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of elegy for piano cello and oboe you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Cello, Oboe, Piano Ensemble: Mixed Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Petofi Elegy Liszt Oboe Cello Duet Petofi Elegy Liszt Oboe Cello Duet sheet music has been read 1156 times. Petofi elegy liszt oboe cello duet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 01:58:45. [ Read More ] Elegy For Chamber Ensemble Elegy For Chamber Ensemble sheet music has been read 3477 times. Elegy for chamber ensemble arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 05:26:45. [ Read More ] Elegy For Oboe Elegy For Oboe sheet music has been read 2674 times. Elegy for oboe arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 17:42:26. [ Read More ] Elegy In C Minor Reflective Oboe Piano Elegy In C Minor Reflective Oboe Piano sheet music has been read 3026 times. Elegy in c minor reflective oboe piano arrangement is for Intermediate level.