1 METHOD1 on CREATIVE and ANALYTICAL METHODS the Cartesian Or the Holmsian Method? As Cairns-Smith Writes in Relation to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press 2015

Jan 15 #1 Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press Sherlockians (and Holmesians) gathered in New York to celebrate the Great Detective's 161st birthday during the long weekend from Jan. 7 to Jan. 11. The festivities began with the traditional ASH Wednesday dinner sponsored by The Adventuresses of Sherlock Holmes at Annie Moore's, and continued with the Christopher Morley Walk led by Jim Cox and Dore Nash on Thursday morn- ing, followed by the usual lunch at McSorley's. The Baker Street Irregulars' Distinguished Speaker at the Midtown Executive Club on Thursday evening was Alan Bradley, co-author of MS. HOLMES OF BAKER STREET (2004), and author of the award-winning "Flavia de Luce" series; the title of his talk was "Ha! The Stars Are Out and the Wind Has Fallen" (his paper will be published in the next issue of The Baker Street Journal). The William Gillette Luncheon at Moran's Restaurant was well attended, as always, and the Friends of Bogie's at Baker Street (Paul Singleton and An- drew Joffe) entertained the audience with an updated version of "The Sher- lock Holmes Cable Network" (2000). The luncheon also was the occasion for Al Gregory's presentation of the annual Jan Whimsey Award (named in memory of his wife Jan Stauber), which honors the most whimsical piece in The Ser- pentine Muse last year: the winner (Jenn Eaker) received a certificate and a check for the Canonical sum of $221.17. And Otto Penzler's traditional open house at the Mysterious Bookshop provided the usual opportunities to browse and buy. -

THE DISTRICT MESSENGER the Newsletter of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE

THE DISTRICT MESSENGER The Newsletter of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE opinions expressed are the editor’s unless noted otherwise no. 165 7th November 1996 To renew your subscription, send 12 stamped, self-addressed $450.00. There’s also a souvenir of the book’s launch: an envelopes or (overseas) send 12 International Reply Coupons or illustrated 8-page octavo booklet: The Coming Out of Holmes & £5.50 or US$11.00 for 12 issues. Dollar checks should be Watson . Copies 1 - 10, with more than 40 relevant autographs, payable to Jean Upton. Dollar prices quoted without are priced at $75.00; copies 11 - 50 are $50.00 each. (*These qualification refer to US dollars. prices are in Australian dollars.*) Fraser Smyth , a friend of great personality and kindness who Kelvin I. Jones (Oakmagic Publications, 2 South Place Folly, gave much to the Society’s meetings and publications, died last Penzance, Cornwall TR18 4JB) has reissued his 1980 month after a long illness. His fascination with the character of monograph Sherlock Holmes & the South Eastern at £2.50 + 50p Mary Morstan resulted in The Diaries of Mrs John H. Watson postage (cheques payable to K.I. Jones). He plans The (privately published, 1995). Our thoughts are with Anna and Psychology of The Hound (£3.50) for the spring, and a guide to their family. the Dartmoor locations of The Hound of the Baskervilles for the Despite mistaken obits, Vassily Livanov (Russian TV’s summer. Holmes) is still alive and working, according to Peter Blau’s The December catalogue from Ian Henry Publications Ltd (20 Scuttlebutt . -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Aaron, Michele, Death and the Moving Image: Ideology, Iconography and I. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015. Ebook. Agane, Ayaan. “Confations of ‘Queerness’ in 21st Century Adaptations.” In Gender and the Modern Sherlock Holmes: Essays on Film and Television Adaptations since 2009, edited by Nadine Farghaly, 160–173. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015. Alberto, Maria. “‘Of dubious and questionable memory’: The Collision of Gender and Canon in Creating Sherlock’s Postfeminist Femme Fatale.” In Gender and the Modern Sherlock Holmes: Essays on Film and Television Adaptations since 2009, edited by Nadine Farghaly, 66–84. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015. Ali, Dhanil. The Curse of Sherlock Holmes. London: MX Publishing, 2013. Altschuler, Eric L. “Asperger’s in the Holmes Family.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Discord 43 (2013): 2238–2239. Andrews, Hannah. Television and British Cinema: Convergence and Divergence since 1990. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2014. Apple History Channel. “Steve Jobs Stanford Commencement Speech,” Apple History Channel. YouTube. 2006. Accessed Sept 16, 2016. https://www. youtube.com/watch?v D1R-jKKp3NA. = Archer, William. “Masks or Faces?” In Actors on Acting, edited by Toby Cole and Helen Krich Chinoy, 74–86. New York: Crown, 1976. Asghar, Rob. “Five Reasons to Ignore the Advice to Do What You Love,” Forbes.com. 2013. Accessed Sept 16 2016. http://www.forbes.com/sites/ robasghar/2013/04/12/fve-reasons-to-ignore-the-advice-to-do-what-you- love/#cb38d9d36351. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 235 B. Poore, Sherlock Holmes from Screen to Stage, Adaptation in Theatre and Performance, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-46963-2 236 BIBLIOGRAPHY Associated Press. -

Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE E-Mail: [email protected]

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE SHERLOCK HOLMES SOCIETY OF LONDON Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE e-mail: [email protected] no. 250 13 March 2005 Thomas W Ross died on 2 January at the age of eighty-one. Old Station Offices, Llanidloes, Powys SY18 6EB; £5.99). This Academic, jazz musician and churchman, Tom Ross wore his sturdy, attractive paperback contains an informative introductory learning lightly and had a great gift for friendship. His 1997 Good essay and eight ingenious and engaging stories. I have admitted Old Index: The Sherlock Holmes Handbook is a distinctly publicly to a dislike of E W Hornung’s tales of the ‘gentleman idiosyncratic reference work . Basil Hoskins , who died on 17 thief’, but I’ve so enjoyed reading John Hall’s new adventures that January aged seventy-five, had a long and successful acting career, I’m determined to give the originals another go! The publishers mainly on the stage, alternating between the classic drama and have a website at www.planetree.com . musical comedy. In 1988 he played the Tiger of San Pedro in Jean-Marc Lofficier of the Black Coat Press (PO Box 17270, Granada’s TV production of Wisteria Lodge , with Jeremy Brett and Encino, CA 91416, USA; website www.blackcoatpress.com ) tells Edward Hardwicke. me that the second volume of stories about the other great Bill Barnes reports the death at the age of ninety-four, in Newcastle, ‘gentleman burglar’ has just been published. Arsène Lupin vs New South Wales, of Sherlock Holmes . Yes, that was his real Sherlock Holmes: The Blonde Phantom by Maurice Leblanc was name! ‘He once attended a Sherlockian convention in Australia and first published in 1906. -

Sherlock Holmes: Behind the Canonical Screen Info Sheet

Sherlock Holmes: Behind the Canonical Screen Edited & introduced by Lyndsay Faye and Ashley Polasek Order it at: www.bakerstreetjournal.com 272 pages, 10" x 7" trade paperback, December 2015 With 42 color and 38 b&w illustrations Contributor Biographies Lyndsay Faye, BSI (“Kitty Winter”) is the internationally bestselling author of the Edgar Award- nominated Timothy Wilde Trilogy, as well as the critically acclaimed pastiche Dust and Shadow: an Account of the Ripper Killings by Dr. John H. Watson. She is a guest writer for the Eisner Award- nominated comic Watson and Holmes, has written numerous short stories for Sherlockian anthologies as well as The Strand Magazine, and “The Case of Colonel Warburton’s Madness” was selected by Otto Penzler and Lee Child for Best American Mystery Stories 2010. An Adventuress of Sherlock Holmes, Baker Street Babe, and Curious Collector, Faye is also a proud volunteer mentor for Girls Write Now and a director-at-large for Mystery Writers of America. Her work has been translated into fourteen languages, and The Gods of Gotham was honored by the American Library Association for Best Historical Fiction. She lives in Queens with her husband and cats. Ashley D. Polasek, Ph.D., FRSA is an internationally recognized expert in the study of Sherlock Holmes adaptations. Both her MA thesis and doctoral dissertation interrogated the subject of Holmes on screen, and she has published several academic articles in leading journals and presented numerous papers exploring various aspects of Sherlockian film and television throughout the U.S., U.K., and Europe. As a frequent reviewer for Oxford UP’s Adaptation, and a member of both the Association of Adaptation Studies and the Literature/Film Association, she is proud to be a point of contact for scholars seeking to publish about Holmes’ screen afterlives. -

Università Di Pisa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Archive - Università di Pisa UNIVERSITÀ DI PISA Dipartimento di Filologia Letteratura e Linguistica Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue e Letterature Moderne Euroamericane TESI DI LAUREA No ghosts need apply: Gothic influences in Doyle’s Holmesian Canon Candidata: Relatrice: Camilla Del Grazia Prof.ssa Roberta Ferrari Anno Accademico 2014/2015 1 Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 4 I. 18th-century Gothic: parameters and perspectives ......................................................... 6 1. Gothic in context: the debate around romance and novel .......................................... 6 2. Past and politics ........................................................................................................ 12 3. Gothic spaces: settings and displacement. ................................................................ 17 4. Themes, plots and characters. ................................................................................... 21 II. From Romantic Gothic to its Victorian descendants. .................................................. 29 1. The reception of Gothic after 1790.......................................................................... -

Book ^ the Adventure of Wisteria Lodge (Annotated)

The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge (Annotated) (Paperback) ^ Doc < PHGGLGYAAP Th e A dventure of W isteria Lodge (A nnotated) (Paperback) By Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015. Paperback. Condition: New. Annotated. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****. The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge is one of the fifty-six Sherlock Holmes short stories written by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. One of eight stories in the volume His Last Bow, it is a lengthy, two-part story consisting of The Singular Experience of Mr. John Scott Eccles and The Tiger of San Pedro, which on original publication in The Strand bore the collective title of A Reminiscence of Mr. Sherlock Holmes. Holmes is visited by a perturbed proper English gentleman, John Scott Eccles, who wishes to discuss something grotesque. No sooner has he arrived at 221B Baker Street than Inspector Gregson also shows up, along with Inspector Baynes of the Surrey Constabulary. They wish a statement from Eccles about the murder near Esher last night. A note in the dead man s pocket indicates that Eccles said that he would be at the victim s house that night. READ ONLINE [ 4.7 MB ] Reviews A must buy book if you need to adding benefit. We have study and so i am sure that i am going to likely to study once again again in the foreseeable future. I realized this book from my i and dad encouraged this ebook to discover. -- Duane Fadel Undoubtedly, this is the best function by any writer. It usually will not charge too much. -

IRREGULARS This List of Investitured (Or Invested)

THE INVESTITURED (OR INVESTED) IRREGULARS This list of Investitured (or Invested) Irregulars is current through September 2021. Asterisks are used to indicate those who have "passed beyond the Reichenbach." The Investitures of Christopher Morley ("The Sign of the Four"), Edgar W. Smith (“The Hound of the Baskervilles”), Julian Wolff ("The Red-Headed League"), Thomas L. Stix Jr. (“The Norwood Builder”), and Vincent Starrett (“A Study in Scarlet”) have been formally retired. There have been 711 Irregular Shillings awarded, and there are 304 living Irregulars. * Abramson, Ben; 1949; The Beryl Coronet * Abromson, Herman; 1977; Lord Cantlemere Accardo, Pasquale; 2002; Gorgiano of the Red Circle Accardo, Peter X.; 2012; Thorneycroft Huxtable * Adams, Charles A.; 1990; The Winter Assizes at Norwich * Addlestone, Alan; 1985; The Addleton Tragedy * Akers, Arthur K.; 1958; The Bishopgate Jewel Case Alberstat, Mark; 2014; Halifax Alcaro, Mary M.; 2020; Ivy Douglas Alvarez, Marino C.; 2015; Hilton Soames * Anderson, Carl H.; 1951; The Resident Patient * Anderson, James L.; 1964; Inspector Baynes, Surrey Constabulary * Anderson, Karen; 2000; Emilia Lucca * Anderson, Poul; 1960; The Dreadful Abernetty Business * Andrew, Clifton R.; 1950; Shoscombe Old Place Andriacco, Dan; 2021; St. Saviour’s, Near King’s Cross Arai, Kiyoshi; 2015; The Shoso-in Near Nara Armstrong, Curtis; 2006; An Actor and a Rare One * Armstrong, George; 1984; John o' Groat's * Armstrong, Walter P., Jr.; 1985; Birdy Edwards * Aronson, Marvin E.; 1968; Penrose Fisher * Ashman, Peter -

His Last Bow the Adventure of Wisteria Lodge

His Last Bow Arthur Conan Doyle His Last Bow Arthur Conan Doyle The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge The Singular Experience of Mr. John Scott Eccles I find it recorded in my notebook that it was a bleak and windy day towards the end of March in the year 1892. Holmes had received a telegram while we sat at our lunch, and he had scribbled a reply. He made no remark, but the matter remained in his thoughts, for he stood in front of the fire afterwards with a thoughtful face, smoking his pipe, and casting an occasional glance at the message. Suddenly he turned upon me with a mischievous twinkle in his eyes. “I suppose, Watson, we must look upon you as a man of letters,” said he. “How do you define the word ‘grotesque’?” “Strange—remarkable,” I suggested. He shook his head at my definition. “There is surely something more than that,” said he; “some underlying suggestion of the tragic and the terrible. If you cast your mind back to some of those narratives with which you have afflicted a long-suffering public, you will recognize how often the grotesque has 1 His Last Bow Arthur Conan Doyle deepened into the criminal. Think of that little affair of the red-headed men. That was grotesque enough in the outset, and yet it ended in a desperate attempt at robbery. Or, again, there was that most grotesque affair of the five orange pips, which led straight to a murderous conspiracy. The word puts me on the alert.” “Have you it there?” I asked. -

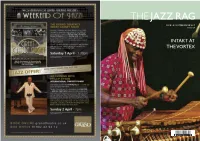

The Jazz Rag

THE JAZZ RAG ISSUE 145 WINTER/SPRING 2017 UK £3.25 INTAKT AT THE VORTEX Photo by Stefan Postius CONTENTS INTAKT RECORDS (PAGE 13) IVORIAN ALY KEITA, MASTER OF THE BALAFON, IS AMONG THE STARS PERFORMING AT INTAKT RECORDS’ FESTIVAL AT THE VORTEX, LONDON. 4 NEWS 7 UPCOMING EVENTS 9 NAT HENTOFF THE GREAT JAZZ WRITER REMEMBERED 10 JAZZ CENTRE UK DIGBY FAIRWEATHER INTRODUCES A MAJOR NEW PROJECT 12 LAST OF THE GUNSLINGERS? SIMON SPILLETT STIRS UP DEBATE 14 ELLA AT 100 SUBSCRIBE TO THE JAZZ RAG SCOTT YANOW ON A NOTABLE CENTENARY THE NEXT SIX EDITIONS MAILED DIRECT TO YOUR DOOR FOR ONLY £17.50* 16 JAZZ RAG CHARTS CDS AND BOOKS Simply send us your name. address and postcode along with your payment and we’ll commence the service from the next issue. 18 JAZZ FESTIVALS MARCH-JUNE OTHER SUBSCRIPTION RATES: EU £24 USA, CANADA, AUSTRALIA £27 21 SOUTHPORT JAZZ FESTIVAL REVIEW Cheques / Postal orders payable to BIG BEAR MUSIC Please send to: 22 CD REVIEWS JAZZ RAG SUBSCRIPTIONS PO BOX 944 | Birmingham | England 31 BOOK REVIEW To pay by debit/credit card, visit www.paypal.me/bigbearmusic and enter the correct amount for your subscription 32 BEGINNING TO CD LIGHT * to any UK address THE JAZZ RAG PO BOX 944, Birmingham, B16 8UT, England UPFRONT Tel: 0121454 7020 33 – AND COUNTING! Fax: 0121 454 9996 The listing of jazz festivals on pages 18-20 suggests a very healthy scene – and, to an Email: [email protected] extent, that is the case -, but doesn’t hint at the hard work, determination and Web: www.jazzrag.com enterprise needed to keep a jazz festival in operation over many years. -

THE TIGER of HAITI by Rick Lai © 2007 Rick Lai [email protected]

THE TIGER OF HAITI by Rick Lai © 2007 Rick Lai [email protected] Scores of theories abound about the true identity of the King of Bohemia encountered by Sherlock Holmes, but very little has been written about man whom Watson disguised as Don Murillo, the Tiger of San Pedro from “The Adventure of the Wisteria Lodge.” To my knowledge, only one solution has been offered concerning Murillo’s real identity. In Dr. Julian Wolff’s Practical Handbook of Sherlockian Heraldry (1955), was suggested that Murillo was Dom Pedro II, the last Emperor of Brazil. However, Dr. Wolff was the first to admit that Dom Pedro was never a despot. We must look elsewhere to ascertain the real name of the Tiger of San Pedro. The search should begin with the country that Watson hid under the alias of San Pedro. Watson portrayed San Pedro as a Central American Republic. San Pedro Sula is a department of Honduras. Fortunately for the people Honduras but unfortunately for my analysis, none of their rulers of the late nineteenth century were as bestial as Don Murillo. Looking elsewhere in Latin America, I discovered that San Pedro is also a department of Paraguay. This country adopted a liberal constitution in 1870 that ushered in a period of political reform for the rest of the century. Don Murillo could never have flourished in such a climate. San Pedro de Macoris is a province in the Dominican Republic. This country presents some intriguing possibilities. The province of San Pedro de Macoris has a capital city of the same name located at the mouth of the Higuamo River. -

His Last Bow

HIS LAST BOW: SH O R T STORIES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES BY SIR AR T H U R CONAN DOYLE © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor This PDF eBook was produced in the year 2010 by Tantor Media, Incorporated, which holds the copyright thereto. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc.