A Majority in the Lifeboat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SINGLE-MEMBER PLURALITY and MIXED-MEMBER PROPORTIONAL ELECTORAL SYSTEMS : Different Concepts of an Election

THE SINGLE-MEMBER PLURALITY AND MIXED-MEMBER PROPORTIONAL ELECTORAL SYSTEMS : Different Concepts of an Election by James C. Anderson A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2006 © James C. Anderson 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-23700-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-23700-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics Economics 2005 Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/law_and_economics Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Adrian Vermeule, "Absolute Voting Rules" (John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper No. 257, 2005). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Economics by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO JOHN M. OLIN LAW & ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER NO. 257 (2D SERIES) Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO August 2005 This paper can be downloaded without charge at: The Chicago Working Paper Series Index: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/Lawecon/index.html and at the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=791724 Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule* The theory of voting rules developed in law, political science, and economics typically compares simple majority rule with alternatives, such as various types of supermajority rules1 and submajority rules.2 There is another critical dimension to these questions, however. Consider the following puzzles: $ In the United States Congress, the votes of a majority of those present and voting are necessary to approve a law.3 In the legislatures of California and Minnesota,4 however, the votes of a majority of all elected members are required. -

A Canadian Model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A

Proportional-first-past-the-post: A Canadian model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Memorial University St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador May 2014 ii Abstract For more than a decade a majority of Canadians have consistently supported the idea of proportional representation when asked, yet all attempts at electoral reform thus far have failed. Even though a majority of Canadians support proportional representation, a majority also report they are satisfied with the current electoral system (even indicating support for both in the same survey). The author seeks to reconcile these potentially conflicting desires by designing a uniquely Canadian electoral system that keeps the positive and familiar features of first-past-the- post while creating a proportional election result. The author touches on the theory of representative democracy and its relationship with proportional representation before delving into the mechanics of electoral systems. He surveys some of the major electoral system proposals and options for Canada before finally presenting his made-in-Canada solution that he believes stands a better chance at gaining approval from Canadians than past proposals. iii Acknowledgements First of foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my brilliant supervisor, Dr. Amanda Bittner, whose continuous guidance, support, and advice over the past few years has been invaluable. I am especially grateful to you for encouraging me to pursue my Master’s and write about my electoral system idea. -

The Concept of Law Revisited

Michigan Law Review Volume 94 Issue 6 1996 The Concept of Law Revisited Leslie Green Osgoode Hall Law School, York University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Leslie Green, The Concept of Law Revisited, 94 MICH. L. REV. 1687 (1996). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol94/iss6/15 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IBE CONCEPT OF LAW REVISITED Leslie Green* THE CONCEPT OF LAW. Second Edition. By H.L.A. Hart. With a Postscript edited by Penelope A. Bulloch and Joseph Raz. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1994. Pp. xii, 315. $26. Law is a social construction. It is a historically contingent fea ture of certain societies, one whose emergence is signaled by the rise of a systematic form of social control and elite domination. In one way it supersedes custom, in another it rests on it, for law is a system of primary social rules that direct and appraise behavior, together with secondary social rules that identify, change, and en force the primary rules. Law may be beneficial, but only in some contexts and always at a price, at the risk of grave injustice; our appropriate attitude to it is therefore one of caution rather than celebration. -

Proximity As the Basis of Political Community Jeremy Waldron

For Workshop on Theories of Territory. KCL, Feb 21 rough draft still Proximity as the Basis of Political Community Jeremy Waldron 1. Introduction A much earlier version of this paper was presented some years ago as the annual Daniel Jacobson Lecture, at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.1 I thought hard before presenting it there. I knew what I wanted to say; I had been thinking about topic for many years. But I worried that half of it would be hopelessly abstract: I was going to be delving into the higher reaches of Kantian political philosophy. And I worried that the other half would be uncomfortably concrete, for what I proposed to do—in Jerusalem, of all places—was to cast doubt on the proposition that it is a good idea for people to form a political community exclusively with those they like, or those who are like them, or those who share with them some affinity or trust based on culture, language, religion, or ethnicity. I wanted to cast doubt on that proposition not by criticizing it directly, but by articulating an alternative approach to the formation of political communities, which I shall call the principle of proximity. The principle of proximity holds that states should be formed among those who (in Immanuel Kant’s phrase) live “unavoidably side by side.”2 A state should be formed among them not on account of any special affinity or trust, but rather on account of the potential conflict that their proximity to one another is likely to engender. People should join in political community with those they are most likely to fight. -

Positivism and the Inseparability of Law and Morals

\\server05\productn\N\NYU\83-4\NYU403.txt unknown Seq: 1 25-SEP-08 12:20 POSITIVISM AND THE INSEPARABILITY OF LAW AND MORALS LESLIE GREEN* H.L.A. Hart made a famous claim that legal positivism somehow involves a “sepa- ration of law and morals.” This Article seeks to clarify and assess this claim, con- tending that Hart’s separability thesis should not be confused with the social thesis, the sources thesis, or a methodological thesis about jurisprudence. In contrast, Hart’s separability thesis denies the existence of any necessary conceptual connec- tions between law and morality. That thesis, however, is false: There are many necessary connections between law and morality, some of them conceptually signif- icant. Among them is an important negative connection: Law is, of its nature, morally fallible and morally risky. Lon Fuller emphasized what he called the “internal morality of law,” the “morality that makes law possible.” This Article argues that Hart’s most important message is that there is also an immorality that law makes possible. Law’s nature is seen not only in its internal virtues, in legality, but also in its internal vices, in legalism. INTRODUCTION H.L.A. Hart’s Holmes Lecture gave new expression to the old idea that legal systems comprise positive law only, a thesis usually labeled “legal positivism.” Hart did this in two ways. First, he disen- tangled the idea from the independent and distracting projects of the imperative theory of law, the analytic study of legal language, and non-cognitivist moral philosophies. Hart’s second move was to offer a fresh characterization of the thesis. -

Incentivising Participation in Liquid Democracy with Breadth-First Delegation

King’s Research Portal Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Kotsialou, G., & Riley, L. (Accepted/In press). Incentivising Participation in Liquid Democracy with Breadth-First Delegation . In International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems 2020: Social Choice and Cooperative Game Theory Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Liquid Democracy: an Algorithmic Perspective

Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 70 (2021) 1223-1252 Submitted 11/2020; published 03/2021 Liquid Democracy: An Algorithmic Perspective Anson Kahng [email protected] Computer Science Department Carnegie Mellon University Simon Mackenzie [email protected] University of New South Wales Ariel D. Procaccia [email protected] School of Engineering and Applied Sciences Harvard University Abstract We study liquid democracy, a collective decision making paradigm that allows voters to transitively delegate their votes, through an algorithmic lens. In our model, there are two alternatives, one correct and one incorrect, and we are interested in the probability that the majority opinion is correct. Our main question is whether there exist delegation mechanisms that are guaranteed to outperform direct voting, in the sense of being always at least as likely, and sometimes more likely, to make a correct decision. Even though we assume that voters can only delegate their votes to better-informed voters, we show that local delegation mechanisms, which only take the local neighborhood of each voter as input (and, arguably, capture the spirit of liquid democracy), cannot provide the foregoing guarantee. By contrast, we design a non-local delegation mechanism that does provably outperform direct voting under mild assumptions about voters. 1. Introduction Liquid democracy is a modern approach to voting in which voters can either vote directly or delegate their vote to other voters. In contrast to the classic proxy voting paradigm (Miller, 1969), the key innovation underlying liquid democracy is that proxies | who were selected by voters to vote on their behalf | may delegate their own vote to a proxy, and, in doing so, further delegate all the votes entrusted to them. -

Incentivising Participation in Liquid Democracy with Breadth-First Delegation∗

Research Paper AAMAS 2020, May 9–13, Auckland, New Zealand Incentivising Participation in Liquid Democracy with Breadth-First Delegation∗ Grammateia Kotsialou Luke Riley Political Economy - King’s College London Informatics - King’s College London, Quant Network London, United Kingdom London, United Kingdom [email protected] luke.riley@{kcl.ac.uk,quant.network} ABSTRACT Party in Argentina and Partido de Internet in Spain have been ex- Liquid democracy allows members of an electorate to either directly perimenting with liquid democracy implementations. Additionally, vote over alternatives, or delegate their voting rights to someone the local governments of the London Southwark borough and the they trust. Most of the liquid democracy literature and implementa- Italian cities Turino and San Dona di Piave are working on integrat- tions allow each voter to nominate only one delegate per election. ing liquid democracy for community engagement processes (Boella However, if that delegate abstains, the voting rights assigned to et al. [2018]). In the technology domain, the online platform Liq- her are left unused. To minimise the number of unused delegations, uidFeedback uses a liquid democracy system where a user selects it has been suggested that each voter should declare a personal a single guru for different topics (Behrens et al. [2014]; Kling etal. ranking over voters she trusts. In this paper, we show that even if [2015]). Another prominent online example is GoogleVotes (Hardt personal rankings over voters are declared, the standard delegation and Lopes [2015]), where each user wishing to delegate can select method of liquid democracy remains problematic. More specifically, a ranking over other voters. -

Selecting the Runoff Pair

Selecting the runoff pair James Green-Armytage New Jersey State Treasury Trenton, NJ 08625 [email protected] T. Nicolaus Tideman Department of Economics, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Blacksburg, VA 24061 [email protected] This version: May 9, 2019 Accepted for publication in Public Choice on May 27, 2019 Abstract: Although two-round voting procedures are common, the theoretical voting literature rarely discusses any such rules beyond the traditional plurality runoff rule. Therefore, using four criteria in conjunction with two data-generating processes, we define and evaluate nine “runoff pair selection rules” that comprise two rounds of voting, two candidates in the second round, and a single final winner. The four criteria are: social utility from the expected runoff winner (UEW), social utility from the expected runoff loser (UEL), representativeness of the runoff pair (Rep), and resistance to strategy (RS). We examine three rules from each of three categories: plurality rules, utilitarian rules and Condorcet rules. We find that the utilitarian rules provide relatively high UEW and UEL, but low Rep and RS. Conversely, the plurality rules provide high Rep and RS, but low UEW and UEL. Finally, the Condorcet rules provide high UEW, high RS, and a combination of UEL and Rep that depends which Condorcet rule is used. JEL Classification Codes: D71, D72 Keywords: Runoff election, two-round system, Condorcet, Hare, Borda, approval voting, single transferable vote, CPO-STV. We are grateful to those who commented on an earlier draft of this paper at the 2018 Public Choice Society conference. 2 1. Introduction Voting theory is concerned primarily with evaluating rules for choosing a single winner, based on a single round of voting. -

Jeremy Waldron Source: Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, New Series, Vol

Participation: The Right of Rights Author(s): Jeremy Waldron Source: Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, New Series, Vol. 98 (1998), pp. 307-337 Published by: Wiley on behalf of The Aristotelian Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4545289 Accessed: 26-08-2014 17:48 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Aristotelian Society and Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.122.149.145 on Tue, 26 Aug 2014 17:48:47 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions XV*-PARTICIPATION:THE RIGHT OF RIGHTS by JeremyWaldron ABSTRACT This paperexamines the role of political participationin a theory of rights. If political participationis a right, how does it stand in relation to other rights aboutwhich the participantsmay be makingpolitical decisions? Suppose a majority of citizens vote in favour of some limit on (say) the free exercise of religion. If their decision is allowed to stand, does that mean that we are giving more weight to the right to participatethan to the right to religious freedom? In this paper, I argue that talk of conflict (and relative weightings) of rights is inappropriatein a case like this. -

Midterm 2. Correction

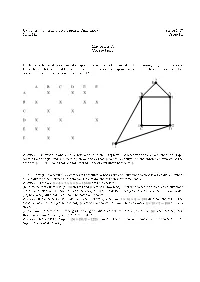

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Spring 2007 Math 181 Group F1 Midterm 2. Correction. 1. The table below shows chemical compounds which cannot be mixed without causing dangerous reactions. Draw the graph that would be used to facilitate the choice of disposal containers for these compounds ; what is the minimal number of containers needed ? 2 E A B C D E F A X X X B A 3 1 B X X X X C X X D X X X 1 2 E X X C D F X X F 1 Answer. The graph is above ; a vertex-coloring of this graph will at least use three colors since the graph contains a triangle, and the coloring above shows that 3 colors is enough. So the chromatic number of the graph is 3, which means that the minimal number of containers needed is 3. 2. (a) In designing a security system for its accounts, a bank asks each customer to choose a ve-digit number, all the digits to be distinct and nonzero. How many choices can a customer make ? Answer. There are 9 × 8 × 7 × 6 × 5 = 15120 possible choices. (b) A restaurant oers 4 soups, 10 entrees and 8 desserts. How many dierent choices for a meal can a customer make if one selection is made from each category ? If 3 of the desserts are pie and the customer will never order pie, how many dierent meals can the customer choose ? Answer. If one selection is made from each category, there are 4 × 10 × 8 = 320 dierent choices ; if the customer never orders pie, he has only 5 desserts to choose from and thus can make 4 × 10 × 5 = 200 dierent choices.