ABSTRACT LIN, MICHELLE- "Only the Blind Are Free": Sight and Blindness in Margaret Atwood's the Blind Assassin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

246 Lavinia TACHE Faculty of Letters, University Of

Lavinia TACHE Faculty of Letters, University of Bucharest Bucharest, Romania [email protected] OBJECTS RECONFIGURING THE PRESENT AND THE PRESENCE. ROUTES OF DISPLACEMENT FOR HUMANS: YOKO OGAWA, HAN KANG, OLGA TOKARCZUK Recommended Citation: Tache, Lavinia. “Objects Reconfiguring the Present and the Presence. Routes of Displacement for Humans: Yoko Ogawa, Han Kang, Olga Tokarczuk.” Metacritic Journal for Comparative Studies and Theory 7.1 (2021): https://doi.org/10.24193/mjcst.2021.11.15 Abstract: The materiality of the human body is to be understood in a complementary relation with the objects that produce an extension of life and the privation of it. The Memory Police (Yoko Ogawa) and Human Acts (Han Kang) reassemble the past through the instrumentalization of objects, thus creating life in the present. The question that arises is whether this certain present can preserve the integrity of the human. Flights by Olga Tokarczuk suggests the body as a locus of conversion and tackles contemporary interests regarding plastic, for instance. These texts authored by Ogawa, Kang and Tokarczuk allow for a repositioning of the standpoint from which the consequences of subject-object relation are approached in literature, because they tap into human experience by addressing the essentiality of objects as repositories of memories. The essay attempts to analyse how objects having either a beneficial or a lethal meaning can be seen as deeply encapsulated in human existence. Keywords: memory, object-oriented theory, subject, bodies, trauma Three realities – objects for a decontextualized humanity Echoing dystopian versions of worlds about the reconfiguration of humanity, both Han Kang and Yoko Ogawa explore the idea that an object may have wide-ranging interpretations. -

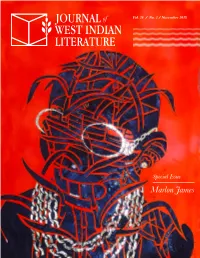

Marlon James Volume 26 Number 2 November 2018

Vol. 26 / No. 2 / November 2018 Special Issue Marlon James Volume 26 Number 2 November 2018 Published by the Departments of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: Sugar Daddy #2 by Leasho Johnson Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2018 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Lisa Outar (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Kevin Adonis Browne BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. JWIL originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt. It reflects the continued commitment of those who followed their lead to provide a forum in the region for the dissemination and discussion of our literary culture. -

The Unquiet Dead: Race and Violence in the “Post-Racial” United States

The Unquiet Dead: Race and Violence in the “Post-Racial” United States J.E. Jed Murr A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Dr. Eva Cherniavsky, Chair Dr. Habiba Ibrahim Dr. Chandan Reddy Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English ©Copyright 2014 J.E. Jed Murr University of Washington Abstract The Unquiet Dead: Race and Violence in the “Post-Racial” United States J.E. Jed Murr Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Eva Cherniavksy English This dissertation project investigates some of the ways histories of racial violence work to (de)form dominant and oppositional forms of common sense in the allegedly “post-racial” United States. Centering “culture” as a terrain of contestation over common sense racial meaning, The Unquiet Dead focuses in particular on popular cultural repertoires of narrative, visual, and sonic enunciation to read how histories of racialized and gendered violence circulate, (dis)appear, and congeal in and as “common sense” in a period in which the uneven dispensation of value and violence afforded different bodies is purported to no longer break down along the same old racial lines. Much of the project is grounded in particular in the emergent cultural politics of race of the early to mid-1990s, a period I understand as the beginnings of the US “post-racial moment.” The ongoing, though deeply and contested and contradictory, “post-racial moment” is one in which the socio-cultural valorization of racial categories in their articulations to other modalities of difference and oppression is alleged to have undergone significant transformation such that, among other things, processes of racialization are understood as decisively delinked from racial violence. -

Locating VS Naipaul

V.S. Naipaul Homelessness and Exiled Identity Roshan Cader 12461997 Supervisors: Professor Dirk Klopper and Dr. Ashraf Jamal November 2008 Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (English) at the University of Stellenbosch Declaration I, Roshan Cader, hereby declare that the work contained in this research assignment/thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature:……………………….. Date:…………………………….. 2 Abstract Thinking through notions of homelessness and exile, this study aims to explore how V.S. Naipaul engages with questions of the construction of self and the world after empire, as represented in four key texts: The Mimic Men, A Bend in the River, The Enigma of Arrival and A Way in the World. These texts not only map the mobility of the writer traversing vast geographical and cultural terrains as a testament to his nomadic existence, but also follow the writer’s experimentation with the novel genre. Drawing on postcolonial theory, modernist literary poetics, and aspects of critical and postmodern theory, this study illuminates the position of the migrant figure in a liminal space, a space that unsettles the authorising claims of Enlightenment thought and disrupts teleological narrative structures and coherent, homogenous constructions of the self. What emerges is the contiguity of the postcolonial, the modern and the modernist subject. This study engages with the concepts of “double consciousness” and “entanglements” to foreground the complex web and often conflicting temporalities, discourses and cultural assemblages affecting postcolonial subjectivities and unsettling narratives of origin and authenticity. -

J. M. Coetzee and the Paradox of Postcolonial Authorship

J. M. Coetzee and the Paradox of Postcolonial Authorship Jane Poyner J. M. COETZEE AND THE PARADOX OF POSTCOLONIAL AUTHORSHIP For Mehdi and my mother J. M. Coetzee and the Paradox of Postcolonial Authorship JANE POYNER University of Exeter, UK © Jane Poyner 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Jane Poyner has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to EHLGHQWL¿HGDVWKHDXWKRURIWKLVZRUN Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Suite 420 Union Road 101 Cherry Street Farnham Burlington Surrey, GU9 7PT VT 05401-4405 England USA www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Poyner, Jane. J. M. Coetzee and the paradox of postcolonial authorship. 1. Coetzee, J. M., 1940– – Criticism and interpretation. 2. Postcolonialism in literature. 3. Politics and literature – South Africa – History – 20th century. 4. South Africa – In literature. I. Title 823.9’14–dc22 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Poyner, Jane. J. M. Coetzee and the paradox of postcolonial authorship / Jane Poyner. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ,6%1 DONSDSHU 1. Coetzee, J. M., 1940 – Criticism and interpretation. 2. Coetzee, J. M., 1940 – Characters – Authors. 3. Authorship in literature. 4. Postcolonialism in literature. 5. South Africa – In -

The Therapy of Humiliation: Towards an Ethics of Humility in the Works of J.M. Coetzee

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2011 The Therapy of Humiliation: Towards an Ethics of Humility in the works of J.M. Coetzee Ajitpaul Singh Mangat [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, Literature in English, Anglophone outside British Isles and North America Commons, Other Psychiatry and Psychology Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mangat, Ajitpaul Singh, "The Therapy of Humiliation: Towards an Ethics of Humility in the works of J.M. Coetzee. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2011. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/896 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Ajitpaul Singh Mangat entitled "The Therapy of Humiliation: Towards an Ethics of Humility in the works of J.M. Coetzee." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Allen Dunn, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Urmila Seshagiri, Amy Elias Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Ajitpaul Singh Mangat entitled “The Therapy of Humiliation: Towards an Ethics of Humility in the works of J.M. -

Michael Ondaatje's Athe English Patient"

Vosi-Apocalyptic War Histories: Michael Ondaatje's aThe English Patient" JOSEF PESCH THE TRADITION of apocalyptic writing in the US is well documented,1 only a few critics have tried to identify aspects of this tradition in Canadian literature.'2 This may be because there is no equivalent in Canada to the apocalyptic expectations on which the US was founded, and thus a literature which reflected such expectations and their disappointment was never written.3 In the latter half of the twentieth century, apocalyptic writing has become popular to a point at which "apocalypse" has lost all its original religious revelatory meaning. It has become a synonym for total destruction, annihilation, and nuclear end of the world. In the often sensationalist novels of this genre, nuclear apoca• lypse merely serves as a useful structural device for generating tension and suspense, in order to produce a teleologically ori• ented, linear development of plot and action as well as a dramati• cally effective, climactic closure. Just a few postnuclear war novels, classics like Russell Hoban's Riddley Walker or Walter M. Miller's A Canticle for Leibowitz (cf. Dowling), have ventured be• yond such structural simplicity. It seems as if it has been forgotten that the biblical apocalypse, as recorded in "The Revelation of St. John," is not just a vision of destruction and end of the world. Here, beginning and end coincide, and a New Jerusalem and new life are promised to the happy few. There is a time after the end, even if that "time" is paradoxically suspended in timeless eternity. -

![Wordsworth, Lucy, and Post-Apartheid Silence in J.M. Coetzee's Disgrace Author[S]: Michael Sayeau Source: Moveabletype, Vol](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2418/wordsworth-lucy-and-post-apartheid-silence-in-j-m-coetzees-disgrace-author-s-michael-sayeau-source-moveabletype-vol-4592418.webp)

Wordsworth, Lucy, and Post-Apartheid Silence in J.M. Coetzee's Disgrace Author[S]: Michael Sayeau Source: Moveabletype, Vol

Article: ‘Oh, the difference to me!’: Wordsworth, Lucy, and Post-Apartheid Silence in J.M. Coetzee's Disgrace Author[s]: Michael Sayeau Source: MoveableType, Vol. 7, ‘Intersections’ (2014) DOI: 10.14324/111.1755-4527.061 MoveableType is a Graduate, Peer-Reviewed Journal based in the Department of English at UCL. © 2014 Michael Sayeau. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) 4.0https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. “Oh, the diference to me!”: Wordsworth, Lucy, and Post-Apartheid Silence in !"! Coet$ee%s Disgrace !"! Coet$ee%s work o)er the past decade has been structured by an am*ivalence bordering on hostility to the forms in which he writes or speaks! His books arrive in the shops mar(ed as “fction,” but readers are more likely to fnd a set o+ essays (as in Diary of a Bad Year/ or academic talks (as in Elizabeth Costello/ than narrative prose! On the other hand, when as(ed to deliver a talk o+ his own – such as the Tanner Lectures at Princeton that formed the basis o+ Lives of the Animals or his No*el Prize acceptance speech in 2003 – Coet$ee has recourse to fctions! In a promotional blur* for Da)id Shields%s 2010 anti-no)elistic polemic Reality Hunger, Coet$ee%s dissatis+action with the con)entional underpinnings o+ the no)el as a form comes in an e)en more caustic form! I, too, am sick o+ the well-made no)el with its plot and its characters and its settings! I, too, am drawn to literature as (as Shields puts it/ ‘a form o+ thinking, consciousness, wisdom-seekin'%! I, too, like no)els that don9t look like no)els!7 But what was it that made this highly respected no)elist, who has won the Boo(er Prize twice and is a No*el laureate, turn so starkly against his own form; 1 Cited in, Zadie Smith, “An essay is an act of imagination. -

Table of Contents Notes for Salman Rushdie: the Satanic Verses Paul

Notes for Salman Rushdie: The Satanic Verses Paul Brians Professor of English, Washington State University [email protected] Version of February 13, 2004 For more about Salman Rushdie and other South Asian writers, see Paul Brians’ Modern South Asian Literature in English . Table of Contents Introduction 2 List of Principal Characters 8 Chapter I: The Angel Gibreel 10 Chapter II: Mahound 30 Chapter III: Ellowen Deeowen 36 Chapter IV: Ayesha 45 Chapter V: A City Visible but Unseen 49 Chapter VI: Return to Jahilia 66 Chapter VII: The Angel Azraeel 71 Chapter VIII: 81 Chapter IX: The Wonderful Lamp 84 The Unity of The Satanic Verses 87 Selected Sources 90 1 fundamental religious beliefs is intolerable. In the Western European tradition, novels are viewed very differently. Following the devastatingly successful assaults of the Eighteenth Century Enlightenment upon Christianity, intellectuals in the West largely abandoned the Christian framework as an explanatory world view. Indeed, religion became for many the enemy: the suppressor of free thought, the enemy of science This study guide was prepared to help people read and study and progress. When the freethinking Thomas Jefferson ran for Salman Rushdie’s novel. It contains explanations for many of its President of the young United States his opponents accused him allusions and non-English words and phrases and aims as well of intending to suppress Christianity and arrest its adherents. at providing a thorough explication of the novel which will help Although liberal and even politically radical forms of Christianity the interested reader but not substitute for a reading of the book (the Catholic Worker movement, liberation theology) were to itself. -

J.M. Coetzee and the Problems of Literature by Benjamin H. Ogden a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick R

J.M. Coetzee and the Problems of Literature by Benjamin H. Ogden A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in English written under the direction of Myra Jehlen and Derek Attridge and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2013 Abstract of the Dissertation J.M. Coetzee and the Problems of Literature by Benjamin H. Ogden Dissertation Directors: Myra Jehlen and Derek Attridge This dissertation traces the evolution of J.M. Coetzee’s thinking concerning literary form in the non-fiction he wrote between 1963 and 1984. During the first two decades of his career, Coetzee completed a Master’s thesis on Ford Madox Ford, a doctoral dissertation on Samuel Beckett, and numerous articles on topics ranging from quantitative stylistics, to linguistics, to classical rhetoric. Although Coetzee’s novels have become among the most widely studied contemporary fiction in the world, his earliest writing about literature has been widely ignored. I argue that in neglecting Coetzee’s early work on literary form scholars have neglected much of his most important thinking concerning both the nature of the novel as a literary genre and literary form itself. If Coetzee’s novels are important in large part because of how they rethink the conventions of fiction, then it is critical to understand that his novels are extensions of the thinking he did as a doctoral candidate in linguistics and literature, and as a professor. -

Feminist Criticism in the Narratives of Arundhati Roy and Mahasweta Devi

Feminist criticism in the narratives of Arundhati Roy and Mahasweta Devi Trabajo de Fin de Grado Autora: Alicia Garrido Guerrero Tutor: Maurice Frank O’Connor Grado en Estudios Ingleses Curso 2017/18 Facultad de Filosofía y Letras CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………… 3 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………….. 4 1.1 Aim……………………………………………………………. 4 1.2 Corpus……………………………………………….………... 5 1.3 Methodology………………………………………………….. 6 1.4 Indian historical context………………………………………. 7 2. Caste and class marginalisation………………………...……………... 9 2.1 Inter-caste and inter-class relationships………...……………. 10 2.2 Abuse of authorial power………………………...…………... 13 2.3 Women against women………………………………………. 16 3. Indian patriarchal society………………………………………………. 18 3.1 Women’s dependence on male relatives……………………… 19 3.2 Women’s duties and responsibilities…………………………. 22 4. Female sexualisation and gender violence……………...……...……… 25 4.1 Exploitation of the female body……………………………… 26 4.2 Gender violence……….……………………………………… 30 5. India today: real facts behind fiction…………………………………... 32 6. Conclusions……………………………………………………………. 35 7. Bibliography…………………………………………………………… 37 2 ABSTRACT Arundhati Roy and Mahasweta Devi are well-known Indian authors that stand out for their continuous vindication of human rights in favour of the most disadvantaged, which includes feminism and the fight against gender-based discrimination. In their works, both writers narrate stories whose female characters suffer marginalisation, abuse and numerous restrictions due to their condition of women. This portrayal of violence and injustice can be understood as a critic upon the Indian caste system, the patriarchy and the objectification of women. These are precisely the aspects that shall be analysed in this work with the purpose of understanding what these authors denounce in their narrations. In particular, the project shall be focused on Roy’s The God of Small Things and Devi’s Outcast and Breast Stories. -

Margaret Atwood's the Testaments As a Dystopian Fairy Tale

The Oswald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English Volume 23 Issue 1 Article 8 2021 Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments as a Dystopian Fairy Tale Karla-Claudia Csürös Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/tor Part of the American Literature Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Literature in English, Anglophone outside British Isles and North America Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Csürös, Karla-Claudia (2021) "Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments as a Dystopian Fairy Tale," The Oswald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English: Vol. 23 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/tor/vol23/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you by the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Oswald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments as a Dystopian Fairy Tale Keywords Margaret Atwood, The Testaments, dystopia, fairy tale, The Handmaid's Tale This article is available in The Oswald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/tor/vol23/iss1/8 THE