Economic Development Strategy Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hall Parking Permits Required Through Finals

12-06-02 01, 03 12/5/02 9:16 PM Page 1 FRIDAY First December 6, 2002 strike WSU volleyball plays first game in NCAA Cloudy tourney today High: 36 | Low: 29 Sports | 5 More weather, Page 2 Volume 108 | No. 76 | [email protected] | www.dailyevergreen.com A student publication of Washington State University | Pullman, Washington ICE BREAKER Holiday shopping possible in Pullman Amy Trang “For what I don’t Daily Evergreen staff get, I can find ’Tis the season for holi- most anything day shopping. As the holiday season in the Palouse approaches, WSU students Mall.” are hitting the stores from Pullman to Seattle on the Christina Thiemann search for the perfect gift sophomore, nutrition for everyone on their lists. For Christina Thiemann, her holiday Pea and Lentil Council and shopping starts at Norwegian national cook- Thanksgiving break. books. Eggnog lattes also Thiemann, a sophomore will be on sale for $1. nutrition major, shops for “It’s a fun time to come most of her gifts in her in, have some goodies, hometown, Tacoma. meet local authors and “For what I don’t get, I enjoy the new holiday can find most everything in extended hours,” said Erin the Palouse Mall or some- Balch, Bookie retail sales where in town,” she said. associate . “If I can’t find it here, then Authors Lance Olsen I usually do last-minute and Joan Burbick will be at shopping at home or go to the event to read excerpts Brendan Dore/Daily Evergreen Spokane.” from their new books and Jon Miller, a senior hotel and restaurant management major, removes snow from his car windshield Tuesday Tarynn Rudee, a junior sign them. -

Roadway &Traffic Operations Strategy

ESTABLISHING MULTI-MODAL STRATEGIES | CHAPTER 4 ROADWAY & TRAFFIC OPERATIONS STRATEGY To serve planned growth, the future transportation system needs multi-modal improvements and strategies to manage the forecasted travel demand. This chapter presents a detailed strategy to improve Moscow’s roadway network and traffic operations over the next 20 years, including network connectivity options, regional circulation enhancements, intersection modifications, and multi-modal street design guidelines. MULTI-MODAL TRANSPORTATION PLAN This page intentionally left blank. Moscow on the Move 4 ROADWAY & TRAFFIC OPERATIONS STRATEGY Supporting the guiding principles of Moscow on the Move, the Roadway & This Transportation Traffic Operations Strategy strives to provide a truly multi-modal Commission “check mark” icon signifies transportation system and improve safety, access, and mobility for all street which actions have unanimous users by identifying strategies, policies, and projects that help achieve support from the Commission. Moscow’s vision for mobility and access. This strategy of Moscow on the Move The icon is a way to illustrate the level of support for identifies opportunities to retrofit existing streets in Moscow and develops the implementation. street grid to improve citywide connectivity for motor vehicles, pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit users. This strategy specifically provides an overview of the existing traffic conditions and how conditions might change by 2035, a street network plan, various design tools that could be applied throughout the city, and descriptions of recommended street projects. FUTURE DEFICIENCIES AND NEEDS Existing and future roadway and traffic operation conditions were assessed to determine the needs and deficiencies of the system. The key areas projected to require improvement or to present future challenges are summarized below. -

Telephone Cross Reference 208-274 - 208-285 1

© 2019 HAGADONE DIRECTORIES Telephone Cross Reference 208-274 - 208-285 1 5871 Fortier Ted 3195 Paz Kelsey 4131 Gravelle Paul & 7731 Rice Vincent A 1162 Genesee Joint School 5871 Sacred Heart Mission 3196 Stern Matthew Carolyn 7741 Fey Bill District #282 208-274 6461 Coeur d’ Alene Tribe 3199 Rumbolz R 4132 Gillispie Jerry D 7860 Heimgartner Lee & 1164 Broemeling Steve R & 6753 Denny Jack & Vivien 3202 Waham James 4139 Munn Steve & Jeannie Chad (Shop) Mary 2011 Dohrman Ed & Lynda 7011 Smart Jeanene & Jerry 3204 Calhoun Sherill L 4231 Erberhardt Roger 7861 Heimgartner Lee & 1174 O’Connell Shawn & 2029 Smith Mary 3206 Burnett Gail 4272 Clemenhagen Marty & Barb Shelly 2031 Wise Dan & Elaine 3208 Jones Laurie Wendy 7881 Steigers Kenneth & 1177 Baumgartner L D & 2051 Way Glenn F & Vivian 208-276 3209 Mohr Craig 4291 Heimgartner Frank Linda Mary 2057 Chapman Samuel & 3213 Marshall Morgan 4300 Hadley Fred 7891 Kirkham Steve & Karen 1185 Haxton William O Daedra 0620 Bruns Matthew & 3214 Lane Jack IV 4302 Dennler Mark 7941 Stenzel Vickie 1188 Holder Ted 2070 Kuntz Rodney Jennifer 3215 Nelsen Dorie 4311 Dennler Bros 7961 D Taylor Construction 1191 Kraut Paul & Maria 2086 Spokane Seed 0621 Hogan Michael & Patti 3216 Ivie Randy 4311 Dennler Tom 7961 Taylor Dale & Mary 1193 Weber Pat Ed Company 3020 Savell G 3218 Bromley T 4312 Dennler Brothers Lou 1201 Becker Dale L 2095 Payne Rupert Jr & 3021 Taylor Dorothy 3220 Hess B 4331 Steigers Rick 7971 Hitchcock Richard 1202 Cutlip Amanda Marjorie 3023 Guinn J 3222 Webb Garrett 4351 Vallem MJ 7999 Dexter Larry -

Investpack for Attaching Staples.Indd

Staples Retail Space Commercial Opportunity palousecommercial.com Shelley L. Bennett 208.301.1623 208.882.3800 [email protected] For Sale or Lease $1,950,000 or $9.187/mo +NNN 233 Warbonnet Rd, Moscow ID Available SF 24,500 Parcel Size 82,098 SF Year Built 1997 Zoning Motor Business NNN Expenses $ 2.00 SF 2014 Taxes $42,196 Daily Traffic Count 20,447 Financing Cash, Conventional Features Currently Staples retail store Located in the areas main commercial center Hwy 95 Frontage Rear loading docks Next to Walmart Building signage Moscow Retail @ a Glance 28 1) Walmart 15) AutoZone 2) Applebees 16) Arby’s 3) Shari’s Restaurant 17) McDonalds 4) Staples 18) Zips 5) U-Haul 19) Marriott Fairfield Inn 6) Hastings 20) Tri State Outfitters 7) Macy’s 21) Cenex 8) Ross 22) Furniture Center 9) Bed Bath & Beyond 23) Fantastic Sam’s 27 10) Rite Aid 24) Idaho Inn 26 25 11) Winco 25) Walgreen’s 12) Buckle 26) Rosaurers Supermarket 13) Buffalo Wild Wings 27) Anytime Fitness 14) Best Western Suites 28) Do-it-Best Hardware 4 1 8 9 10 11 12 7 19 22 14 3 16 6 20 15 23 13 5 21 17 18 2 24 Downtown Moscow Pullman, WA & Washington University State University of Idaho 6 Miles West On the border of Idaho and Washington this 24,500 sq ft RETAIL STORE is located off Pullman Rd. High traffic and visibility area. Loading docks in the back. 100 Parking spaces. 1 Block west of the Palouse Mall, adjacent to Walmart Superstore, Applebee’s, Shari’s, New Regional Goodwill and La Quinta Hotel. -

2019 | 2020 Downtown Moscow State Highway 8

VISITOR'S GUIDE THAT MOMENT gritman.org BETWEEN MAKING A GRADE AND MAKING AN IMPACT. Exceptional care that’s close to home. It starts with an idea. Then grows into a bigger idea. At Idaho’s premier research university, the contagiousness of • 24/7 Emergency Services possibility leads to doing more, seeing more and learning • QuickCARE walk-in clinic more. And with over 300 academic programs to choose • Advanced diagnostic imaging from, your breakthrough is just around the corner. • Comprehensive surgical and hospital services UIDAHO.EDU/AROUND-THE-CORNER • Regional network of primary care clinics MOSCOW • POTLATCH • KENDRICK • TROY 2019 | 2020 Downtown Moscow State Highway 8 Pullman, WA State Highway 8 3rd Street 120 Perimeter Drive Perimeter N Student Activity Fields Line Street Line Home Street Home Stadium Drive 124 Paradise Creek Street Perimeter Drive 106 35 116 Street Asbury 48 61 3 93 34 Farm Road 65 36 112 6th Street Downtown 6th Street Moscow 6th Street 6th Street 66 26 9 PerimeterDrive 2 43 20 75 87 6th Street Extension 108 51 33 Elm Street 4 Street Ash 32 Deakin Avenue Deakin Rayburn Street Rayburn 42 56 68 86 113 52 46 7th Street 62 40 30 81 74 72 21 10 114 96 71 Narrow Street 89 Stadium Drive 19 29 91 79 17 41 73 27 83 Idaho Avenue Extension Idaho Avenue 60 Idaho Avenue 14 44 54 69 80 39 118 58 117 12 Downtown 103 College Avenue Moscow Elm Street 63 Street Ash 22 Perimeter Drive 78 Avenue Deakin Student Activity 13 Stadium Drive Fields University Avenue 121 ASUI Kibbie Dome 15 Activity Center 122 28 101 70 49 16 38 45 123 59 57 24 94 Sweet Avenue Avenue Deakin 107 Railroad Street 25 11 77 Old Pullman Road 110 55 1 5 Tennis Perimeter Drive Courts 82 Rayburn Street Blake Avenue 64 23 Campus Drive Deakin Avenue Deakin Nez Perce Drive Sweet Avenue 119 115 Tennis Courts 31 90 76 85 18 47 92 125 105 67 100 111 98 50 8 37 109 53 6 104 Nez Perce Drive 97 84 99 Highway 95 Blake Avenue 7 102 Boise Taylor Avenue Taylor Avenue VISITOR'S GUIDE WELCOME TO MOSCOW! WE ARE GLAD YOU ARE HERE. -

Uxiversi I'y of Idaho

UXIVERSI I'Y OF IDAHO 7'he l~aaclal l~oicc S6 (ee 1898 Friday, Sept. 1/i, 2007 Volume 108, No. 10 DARFU R I'ISIS Bicycles without headlights will be fined $46.50 inS ires Greg Connolly Argonaut In today's gasoline driven world, BC IQn the bicycle plays a crucial role in transportation for college students. Lianna Shepherd What many riders fail to acknowl- edge are the city and state codes Argonaut that exist for their safety. sophomore Travis Thompson According to Idaho law, the same When in New Zealand and Aus- trafflc laws to bikes and other studied abroad apply tralia, gained more than a larger back- human-energy propelled vehicles he ground in anthropology, he gained a mis- that apply to cars and trucks. This includes the use of headlights after sion. Shocked the treatment of Aborigines sunset. Bicycle lights must illumi- by Thompson sought to learn nate at least 500 feet ahead. Bikes in Australia, more about modern atrocities. also must have a reflector clearly "It was like I was a little kid "Thomp- displayed on the back of the bike. son said. "I wanted to know if there was "The law of gross tonnage says more of this stuff going on.", . that the biggest object usually wins. Thompson eventually decided to re- between a three quarter ton So, search Sudan and read "The Devil Came suburban truck and a bicycle, right Horseback," Brian Steidle. Accord- suburban's to on by or wrong, the going it was mind blowing." win," said Lt. Paul Kwiatkowski of ing to Thompson, "It's one thing for someone not to know, the Moscow Police Department. -

C Ross C~Air

Sept.19,1880; Vol. 85, No. 8; University of idaho friday .~ ' jili I Argoneut Photo/Gerard Oulnn 'bavid Giese, assistant professor of art, shows an embroidered Japanese art piece during the opening day—of the U of I Gallery's Palouse Collector's show =ooI; va a ayer c ross c ~air 'ro "ower Larry Barker, a starting defensive end on the Vandal swimming pool about a half hour after closing time. against Barker was dismissed by District Judge Robert football team, was suspended indefinitely Wednesday by Davitch said Berker's dropping the chair was just one of Felton. Felton said that probable cause had not been head coach Jerry Davitch. several incidents that led to his decision to suspend Barker shown by the complainant, Stan Slutz of Troy. Slutz filed last Barker had beaten him Barker, a 216.pound senior from Medford, Ore., drop- for at least one game. the complaint spring, saying last Dec. 12. ped a chair from the seventh floor of the Theophilus Tower "As far as the length the it's of suspension, something In April of 1978, Barker pleaded guilty to a battery Monday night. The chair struck freshman Joel Semanko, I'l just sit on," Davitch "I like : said. feel a parent of 100 charge and was given a withheld judgment. After a ~ who was walking out of the building. kids and have I responsibilities to them all, including 13-month probation period, the charges against Barker Larry. I felt had Semanko, an architecture major from Post Falls, re- just I to do something." were dismissed. -

Fiscal Year 2021 Budget Summary

CITY OF MOSCOW Municipal Budget Summary ADOPTED Fiscal Year 2021 Bill Lambert Gary J. Riedner Mayor City Supervisor Brandy Sullivan Maureen Laflin Council President Council Member Art Bettge Gina Taruscio Council Vice-President Council Member Sandra Kelly Anne Zabala Council Member Council Member TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 5 BUDGET DOCUMENT & GUIDE ...................................................................................................................... 5 CITY MISSION STATEMENT .............................................................................................................................. 6 STRATEGIC PLANNING PROCESS ..................................................................................................................... 7 Completed Issues .................................................................................................................................................... 8 Discontinued Issues ................................................................................................................................................ 9 Disrupted Issues ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 2020 City Council Workshop................................................................................................................................ 10 Tier -

A TOUCH of GLASS Acey Dennis E

© 2020 HAGADONE DIRECTORIES AAA - ADAMS 1 A A ASE Orofino ................................................................208-476-7476 Ace Elliott Land ASPNS 165 NE Kamiaken St Pul ............................509-334-3505 PO Box 301 Hwy 27 At Whelan Road Pul ..........509-332-2928 AAA Precision Tool & Cutter Grinding LLC AT&T 1850 W Pullman Rd Mscw ............................208-882-3402 Ace Hardware 610 S Main St Colfax....................509-397-4102 101 College Ave Orf..................................................208-476-4004 A To Z Family Services 205 107th St Orf ........208-476-7483 Ace Home Center 139 E Main St Grngvl ..........208-983-0933 AAA Ride Cab Lwstn/Clrkstn..................................208-743-3222 Ace Marketplace 403 Main St Kamiah................208-935-2522 A & A AUTO REPAIR & TOWING Aceves B Orf ................................................................208-476-9961 A TOUCH OF GLASS Acey Dennis E ..........................................................509-758-5448 Lewiston ................................................................208-743-4310 Acey’s Landscape Services ..............................509-758-5448 3406 4th St Lewiston .............. A & A Septic Service 208-750-1064 Achenbach J B 1761 Drury Rd Deary ................208-877-1279 95 Grangemont Rd Orf ............................................208-476-9143 Achieving Total Health A & W Restaurant 317 S Main Mscw..................208-882-2301 AAU OFFICE 2004 W Pullman Rd Mscw ......................................208-882-0149 Aaltonen -

111470 T&F Mg Text.Indd

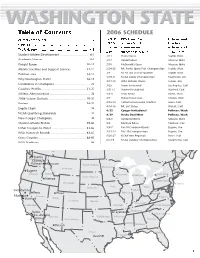

Table of Contents 2006 SCHEDULE Alumni Competitors ................................................... 2 1/20-21 WSU Indoor Open Pullman, Wash. Cougar Facts .............................................................. 3 1/27-28 Pole Vault Summit Reno, Nev. 1/27-28 Cougar Indoor Pullman, Wash. The University .......................................................... 4-5 2/10-11 Holiday Inn Team Invite Nampa, Idaho Student-Athlete Development ................................. 6-7 2/11 Husky Classic Seattle, Wash. Academic Honors .................................................... 8-9 2/17 Vandal Indoor Moscow, Idaho Weight Room ...................................................... 10-11 2/18 McDonald’s Open Moscow, Idaho Athletic Facilities and Support Services ................. 12-13 2/24-25 Mt. Pacifi c Sports Fed. Championships Seattle, Wash. Pullman area ........................................................ 14-17 3/4 NCAA Last Chance Qualifi er Seattle, Wash. 3/10-11 NCAA Indoor Championships Fayetteville, Ark. Why Washington State? ....................................... 18-19 3/17-18 Willie Williams Classic Tucson, Ariz. Alaska Conference of Champions ........................................ 20 3/25 Trojan Invitational Los Angeles, Calif. Coaches’ Profi les .................................................. 21-27 3/31-4/1 Stanford Invitational Stanford, Calif. Athletic Administration ............................................. 28 4/5-8 Texas Relays Austin, Texas 2006 Season Outlook ......................................... -

E Ain Overs E

C II ) .ON THE WE argonaut.illdaiio.edn THESTUDENTS V,„ICE -~j NCE 8 9 8 coNTAGT og: urguuuululdulig+II '. r qThe life nf a musician < I whole different daseline DDD students prepare for annual A.77ChhkoVt7 makeS rl >lelv hOme extravaganza —Sports, Page 11 —Artsd Entertlti ament, Page 8 Arabs issue Israel an ultimatum e ain overs e BY S(1RAYA SARIIADI)l Nsl.sos l(NI(ll)T l(ll)l)l:I( NFI((')I(AI'I:IIN Dress questions moti ves EIRUT, Lebanon — Saudi Crown Prince J ". Abdullah will present the Arab League's newly g adopted peace initiative to President Bush at draws ug his Texas ranch nex1 month, with hopes of convincing for patriotism, fire the United States to put, pressure on Israel io agree to the terms, Arab leaders said Thursday. The seven-part initiative, unveiled after the close BY IY()NNE Rl VERA of the organization's annual summit, includes an Al();()NAI'I' I'AFI. unprecedented offer of "normal relations" between all Arab countries and Israel in exchange for the Jewish state relinquishing land conquered in the Six Day he Wearable Art Collection on display at the War in 1967, But the Arab proposal —a compromise between University of Idaho's library is facing criticism " moderate and hard-line Arab states —may not be from many on campus. In the center of the con- * r ~ bold enough to gei, Israeli Prime Minister Ariel a Sharon to start negotiating, especially when his troversy stands a dress made of American flag fabric wu. nation is the target of a new wave of terrorist attacks. -

Visitor's Guide

VISITOR’S GUIDE – W E S E L L A DV E N T U R E G E A R MOSCow F O R A DV E N T U R E L OV E R S Step Outside With Us. Kayak & Canoe Sales & Rentals Hunting, Fishing & Camping Gear Fish & Game Tags & Licenses Barbeques & Smokers Beer & Wine Brewing Supplies Gourmet Snacks & Idaho Gifts Moscow. It rhymes with “Let’s go.” 208-882-4555 w w w. t r i s t a t e o u t f i t t e r s . c o m A C R O S S T H E PU L L M A N R O A D F R O M T H E U. I . CA M PU S WELCOME TO MOSCOW! WE ARE GLAD YOU ARE HERE. The community of Moscow invites you CHAMBER STAFF to experience what we have to offer – Jenny Ford, Executive Director interesting shops, a historic downtown, Kendra Ewing, Office Assistant sumptuous restaurants, exciting museums Gabriela Franco, Receptionist and art galleries, and even blockbuster Laura Kirkland, Receptionist movies. Hike, bike, golf, relax – you can do it all in Moscow. FOR MORE INFORMATION CONTACT US! The Moscow Chamber of Commerce Moscow Chamber of Commerce welcomes you. If you would like 411 South Main St. • (208) 882-1800 visitor information, a restaurant [email protected] recommendation, or directions to a thrift shop we are located downtown. Our downtown gathering spot is called Friendship Square – a perfect illustration of who we’ve always been. We know you will love it here! MOSCOW CHAMBER photo courtesy of Ryan Zimmer Photography OF COMMERCE Committed to a Strong Community Just as we invent new products to improve power grids in communities around the world, we find new ways to strengthen our own community on the Palouse every day.