An Appraisal of Challenges in the Sustainable Management of the Micro-Tidal Barrier-Built Estuaries and Lagoons in Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthropogenic Impacts on Urban Coastal Lagoons in the Western and North-Western Coastal Zones of Sri Lanka

1 2 Anthropogenic Impacts on Urban Coastal Lagoons in the Western and North-western Coastal Zones of Sri Lanka Jinadasa Katupotha Department of Geography, University of Sri Jayewardenepura Gangodawila, Nugegoda 10250, Sri Lanka [email protected] Abstract Six lagoons from Negombo to Puttalam, along the Western and North Western coast of Sri Lanka, show signs of some change due to urbanization-related anthropological activities. Identified activities have direct implications on morphological features of lagoons, elimination of wetlands (mangrove swamps and marshy lands) and pasture lands, land degradation due to encroachment for shrimp farms, shrinking of lagoons, and production of higher nutrient and heavy metal loads, decline in bird and fish populations and degradation of the scenic beauty. As a result, the lagoon ecosystems have suffered to such a degree that numerous faunal and floral species have disappeared or have diminished considerably over the last few years. All these anthropogenic impacts were identified by the author during 1992, 2002, and 2006 as well as in a study on “Lagoons in Sri Lanka” conducted by IWMI between 2011 and 2012. Key words: Anthropogenic Impacts, Urban Coastal Lagoons, Garbage accumulation, Awareness program Introduction The island of Sri Lanka has 82 coastal lagoons that support a variety of plants and animals, and the economy [1]. Anthropogenic impacts, particularly lagoon fishing, human occupation of the land and water contamination have considerably reduced the faunal and floral population to a point that some of them are in danger of extinction. Such danger of extinction has been accelerated in urban lagoons of the western and northwestern coastal zones, e.g. -

Evolutionof Coastallaridformsinthe Western Part of Srilanka

HiroshimaHiroshimaGeographicalAssociation Geographical Association Geographical Sciences vol, 43 no.1 pp, 18-36, 1988 Evolution of Coastal Laridforms inthe Western Part of Sri Lanka JINADASA KATUPOTHA* Key Words:evolution of coastal landforms, SriLanka, late Pleistocene, Holocene, landfOmi classMcation Abstract Geomorphic and geologic evidence shows four different stages {Stage I-IV} in the evolution of coastal landforrns on the west coast of Sri Lanka during the Iate Pleistocene and Holocene Epochs. The author assumes that the old ridges in Stage I at Sembulailarna, Kiriyanl(ailiya, Pambala, Wiraliena, Uluambalarna and Kadrana areas have been fonned precedng the Holocene transgression. Low hMs and ridges in the area were coated mainly by wind blown sand, fonowing the lower sea levels during the Late Pleistocene and Earty Holocene Epochs. Radiocarbon datings en the west and seuth coast$ reveal that the sea level remained 1rn or more above the present sea level between 6170± 70 and 535e± 80 yr B. P. During this transgression, the forTner drainage basins were submerged and headland bay beaches were ereated. Many wetlands aiid beach ridges, particularly in Stages ll, III, and IV were gradualy formed owing to rninor oscMations of sea levet after mid-Holocene. Most of these landiorTns haveaclose relationship with main climatic zenes of the country. 1987; Katupotha, 1988) also help to deterrnine their I. Introduction evolution. The island of Sri Lanka has a coastline over Coastal Iandform maps of the study area were 1920 km in length, exhibiting a diversity of coastal cornpiled by means of interpretation of aerial photo- landromis. The coastal lowlands with elevation graphs (1:40,OOO-Survey Department of Sri Lanka, from mean sea level (MSL) to 30m consist of 1956) and field observations. -

Ecological Biogeography of Mangroves in Sri Lanka

Ceylon Journal of Science 46 (Special Issue) 2017: 119-125 DOI: http://doi.org/10.4038/cjs.v46i5.7459 RESEARCH ARTICLE Ecological biogeography of mangroves in Sri Lanka M.D. Amarasinghe1,* and K.A.R.S. Perera2 1Department of Botany, University of Kelaniya, Kelaniya 2Department of Botany, The Open University of Sri Lanka, Nawala, Nugegoda Received: 10/01/2017; Accepted: 10/08/2017 Abstract: The relatively low extent of mangroves in Sri extensively the observations are made and how reliable the Lanka supports 23 true mangrove plant species. In the last few identification of plants is, thus, rendering a considerable decades, more plant species that naturally occur in terrestrial and element of subjectivity. An attempt to reduce subjectivity freshwater habitats are observed in mangrove areas in Sri Lanka. in this respect is presented in the paper on “Historical Increasing freshwater input to estuaries and lagoons through biogeography of mangroves in Sri Lanka” in this volume. upstream irrigation works and altered rainfall regimes appear to have changed their species composition and distribution. This MATERIALS AND METHODS will alter the vegetation structure, processes and functions of Literature on mangrove distribution in Sri Lanka was mangrove ecosystems in Sri Lanka. The geographical distribution collated to analyze the gaps in knowledge on distribution/ of mangrove plant taxa in the micro-tidal coastal areas of Sri occurrence of true mangrove species. Recently published Lanka is investigated to have an insight into the climatic and information on mangrove distribution on the northern anthropogenic factors that can potentially influence the ecological and eastern coasts could not be found, most probably for biogeography of mangroves and sustainability of these mangrove the reason that these areas were inaccessible until the ecosystems. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

A Strategy for Nature Tourism Management

I I I A STRATEGY FOR NATURE TOURISM I MANAGEMENT: I Review of the EnvIronmental and Economic Benefits I of Nature TourIsm and Measures to Increase these Benefits I By I H M 8 C Herath M Sivakumar I P Steele I FINAL REPORT I August 1997 I Prepared for the Ceylon Tourrst Board and Department of Wildlife I USAIDI Natural Resources & Environmental Polley Project International Resources Group (NAREPP/IRG) I A project of the United States Agency for International Development and the I Government of Sri Lanka I I I I I I I DlScriptlOllS about Authors Mr HMC Herath IS a Deputy DIrector workIng for Department of WIldlIfe I ConservatIon, 18, Gregory's Road, Colombo 07, TP No 94-01-695 045 Mr M Sivakurnar IS a Research asSIStant, EnvIronmental DIvISIon Mmistry of I Forestry and EnvIronment, 3 rd Floor, Umty Plaza Bmldmg, Colombo 04 Mr Paul Steele IS an EconomIC Consultant workIng for EnvIronmental DIvISIon, I MllliStry of Forestry and EnvIronment, 3 rd Floor, Umty Plaza BUlldmg, Colombo 04 I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I CONTENTS I Page I Executive Summary 1-11 1 IntroductIOn 12 I 2 EXIstmg market for nature tounsm 13-19 I 3 Survey of eXIstIng nature tounsm sItes 20-35 4 EnvIronmental and economIC ObjectIves of a I nature tounsm management strategy 36-42 5 QuantIfymg the economiC benefits from nature tounsm 43-56 I 6 ActI\ ltles and SItes for dIversIfymg and expandIng nature tounsm 57-62 I 7 ConclUSIOns and RecommendatIons for IncreasIng the e'1\ Ironmental and economIC benefits of I nature tounsm 63-65 8 References 66 I 9 Annex 1 LIst of persons consulted 67-68 I Annex 2 Graphs of VIsItor entrance and revenues 69-77 Annex 3 Summary of RecommendatIons of Nature Tounsm Workshop and LISt I of PartIcipants 78-80 I I I I I I I Executive summary I 1 Nature tOUrIsm should be promoted by the Ceylon TourlSt Board to mcrease the number of tourlSts vlSlt10g Sn Lanka. -

Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA34481 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 11 March 2009 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo – International Business Systems Institute – Education system – Sri Lankan Army-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam conflict – Risk of arrest This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. 2. Is it likely that someone would attain a high school or higher education qualification in Sri Lanka without learning a language other than Tamil? 3. Please provide an overview/timeline of relevant events in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka from 1986 to 2004, with particular reference to the Sri Lankan Army (SLA)-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) conflict. 4. What is the current situation and risk of arrest for male Tamils in Batticaloa and Colombo? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. Note: Kaluvanchikkudy is also transliterated as Kaluwanchikudy is some sources. No references could be located to the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. The Education Guide Sri Lanka website maintains a list of the “Training Institutes Registered under the Ministry of Skills Development, Vocational and Tertiary Education”, and among these is ‘International Business System Overseas (Pvt) Ltd’ (IBS). -

Fisheries Management Provisions

FISHERIES INSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS AND CAPACITY ASSESSMENT TO THE MINISTRY OF FISHERIES AND AQUATIC RESOURCES, SRI LANKA APPENDIX I: Fisheries Management provisions Table I.1: Fisheries co-management principles Participatory Fisheries Resource Meaning Management Principles The spirit of governance and administration are the interests of the people of Sri Lanka, based on their own aspirations. Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Under decentralization of the fisheries management process, DFAR and the District Fisheries Offices are the responsible Resources is responsible for facilitating the stakeholders: the decision-makers. Hence, these regional fisheries agencies are also responsible for facilitating the management of national and coastal fisheries management of regional fisheries resources by providing human and financial resources to support PFRM as a resources. framework for the management of regional and national fisheries resources. Stakeholders are the participants of fisheries management. The spirit of decentralization of decision-making is that stakeholders should decide on how their aspirations can be met. Stakeholders include: fishermen using different gear types; fish traders; fish processors; fisheries scientists and researchers; coastal communities; fish and plant farmers; district fisheries agencies and the central and district government fisheries agency (DFAR). Stakeholders of participatory coastal fisheries resource management are the coastal The selection of the appropriate stakeholder groups, to be involved in fisheries resource management, should be carried communities, private sectors and government out through stakeholder analysis and the best people to represent these groups chosen democratically. Stakeholder agencies. representatives must have the confidence of the group they represent to ensure ownership of decisions and the empowerment of the stakeholder groups. The social and cultural differences of stakeholders should be formally accepted as input into the decision making process. -

The Government of the Democratic

THE GOVERNMENT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE GOVERNMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2019 DEPARTMENT OF STATE ACCOUNTS GENERAL TREASURY COLOMBO-01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. 1. Note to Readers 1 2. Statement of Responsibility 2 3. Statement of Financial Performance for the Year ended 31st December 2019 3 4. Statement of Financial Position as at 31st December 2019 4 5. Statement of Cash Flow for the Year ended 31st December 2019 5 6. Statement of Changes in Net Assets / Equity for the Year ended 31st December 2019 6 7. Current Year Actual vs Budget 7 8. Significant Accounting Policies 8-12 9. Time of Recording and Measurement for Presenting the Financial Statements of Republic 13-14 Notes 10. Note 1-10 - Notes to the Financial Statements 15-19 11. Note 11 - Foreign Borrowings 20-26 12. Note 12 - Foreign Grants 27-28 13. Note 13 - Domestic Non-Bank Borrowings 29 14. Note 14 - Domestic Debt Repayment 29 15. Note 15 - Recoveries from On-Lending 29 16. Note 16 - Statement of Non-Financial Assets 30-37 17. Note 17 - Advances to Public Officers 38 18. Note 18 - Advances to Government Departments 38 19. Note 19 - Membership Fees Paid 38 20. Note 20 - On-Lending 39-40 21. Note 21 (Note 21.1-21.5) - Capital Contribution/Shareholding in the Commercial Public Corporations/State Owned Companies/Plantation Companies/ Development Bank (8568/8548) 41-46 22. Note 22 - Rent and Work Advance Account 47-51 23. Note 23 - Consolidated Fund 52 24. Note 24 - Foreign Loan Revolving Funds 52 25. -

Sri Lanka Date: 19 September 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA33744 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 19 September 2008 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Freedom of movement – Checkpoints This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Can you please provide information on the ease with which people could travel in the east and north of Sri Lanka during 2002, and also in subsequent years until 2006? 2. Please include any information about check points. RESPONSE 1. Can you please provide information on the ease with which people could travel in the east and north of Sri Lanka during 2002, and also in subsequent years until 2006? 2. Please include any information about check points. Sources indicate that travel to the north and east of Sri Lanka was possible between 2002 and 2006 due to the signing of the peace agreement between the Sri Lankan Army (SLA) and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam (LTTE) in 2002. This agreement, whilst not adhered to by either party, at least reduced full scale military activity in then LTTE-held areas, -

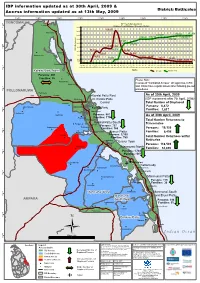

IDP Numbers and Access 30042009 GA Figures

IDP information updated as at 30th April, 2009 & District: Batticaloa Access information updated as at 13th May, 2009 81°15'0"E 81°20'0"E 81°25'0"E 81°30'0"E 81°35'0"E 81°40'0"E 81°45'0"E 81°50'0"E 81°55'0"E TRINCOMALEE (! IDP Trend - Batticaloa District Verugal Returnees Trend - Batticaloa / Trincomalee Districts 8°15'0"N 180,000 159,355 (! 160,000 Kathiravely 136,084 137,659 140,000 127,837 119,527 120,742 136,555 120,000 132,728 97,405 100,000 108,784 72,986 80,000 81,312 8°10'0"N IDPs/Returnees 60,272 68,971 60,000 51,901 (! Vaharai (! 52,685 38,230 Kaddumurivu 40,000 38,121 26,484 24,987 17,600 18,171 12,551 20,000 8,020 1,140 8,543 6,872 (! 0 Panichankerny Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May June July Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2009 2009 2009 2009 8°5'0"N Months IDP Trend Returnees' Trend Koralai Pattu North A 1 Persons: 201 5 Families: 55 (! Please Note: Kirimichchai In areas of "Controlled Access" UN agencies, ICRC Mankerny (! and INGO have regular access after following pre-set procedures. -

Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka Report

Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka A multi-agency approach coordinated by Central Environment Authority and Disaster Management Centre, Supported by United Nations Development Programme and United Nations Environment Programme Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka November 2014 A Multi-agency approach coordinated by the Central Environmental Authority (CEA) of the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy and Disaster Management Centre (DMC) of the Ministry of Disaster Management, supported by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Integrated Strategic Environment Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka ISBN number: 978-955-9012-55-9 First edition: November 2014 © Editors: Dr. Ananda Mallawatantri Prof. Buddhi Marambe Dr. Connor Skehan Published by: Central Environment Authority 104, Parisara Piyasa, Battaramulla Sri Lanka Disaster Management Centre No 2, Vidya Mawatha, Colombo 7 Sri Lanka Related publication: Map Atlas: ISEA-North ii Message from the Hon. Minister of Environment and Renewable Energy Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is a systematic decision support process, aiming to ensure that due consideration is given to environmental and other sustainability aspects during the development of plans, policies and programmes. SEA is widely used in many countries as an aid to strategic decision making. In May 2006, the Cabinet of Ministers approved a Cabinet of Memorandum -

The Effect of Water Bodies As a Determinant Force in Generating Urban Form

The Effect of Water Bodies as a Determinant Force in Generating Urban Form. A Study on Creating a Symbiosis between the two with a case study of the Beira Lake, City of Colombo. K. Pradeep S. S. Fernando. 139404R Degree of Masters in Urban Design 2016 Department of Architecture University of Moratuwa Sri Lanka The Effect of Water Bodies as a Determinant Force in Generating Urban Form. A Study on Creating a Symbiosis between the two with a case study of the Beira Lake, City of Colombo. K. Pradeep S. S. Fernando. 139404R Degree of Masters in Urban Design 2016 Department of Architecture University of Moratuwa Sri Lanka THE EFFECT OF WATER BODIES AS A DETERMINANT FORCE IN GENERATING URBAN FORM - WITH A STUDY ON CREATING A SYMBIOSIS BETWEEN THE TWO WITH A CASE STUDY OF THE BEIRA LAKE, CITY OF COLOMBO. Water bodies present in Urban Contexts has been a primary determinant force in the urban formation and settlement patterns. With the evolutionary patterns governing the cities, the presence of water bodies has been a primary generator bias, thus being a primary contributor to the character of the city and the urban morphology. Urban form can be perceived as the pattern in which the city is formed where the street patterns and nodes are created, and the 03 dimensional built forms, which holistically forms the urban landscape. The perception of urban form has also been a key factor in the human response to the built massing, and fabric whereby the activity pattern is derived, with the sociological implications. DECLARATION I declare that this my own work and this dissertation does not incorporate without acknowledgment any material previously submitted for a Degree or Diploma in any University or any Institute of Higher Learning and to the best of my knowledge and belief it does not contain any materials previously published or written by another person except where acknowledgement is made in the text.