Technical Efficiency of Smallholder Farmers in Red Pepper Production In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Knowledge and Attitude of Pregnant Women Towards Preeclampsia and Its Associated Factors in South Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopi

Mekie et al. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2021) 21:160 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03647-2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Knowledge and attitude of pregnant women towards preeclampsia and its associated factors in South Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: a multi‐center facility‐ based cross‐sectional study Maru Mekie1*, Dagne Addisu1, Minale Bezie1, Abenezer Melkie1, Dejen Getaneh2, Wubet Alebachew Bayih2 and Wubet Taklual3 Abstract Background: Preeclampsia has the greatest impact on maternal mortality which complicates nearly a tenth of pregnancies worldwide. It is one of the top five maternal mortality causes and responsible for 16 % of direct maternal death in Ethiopia. Little is known about the level of knowledge and attitude towards preeclampsia in Ethiopia. This study was designed to assess the knowledge and attitude towards preeclampsia and its associated factors in South Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. Methods: A multicenter facility-based cross-sectional study was implemented in four selected hospitals of South Gondar Zone among 423 pregnant women. Multistage random sampling and systematic random sampling techniques were used to select the study sites and the study participants respectively. Data were entered in EpiData version 3.1 while cleaned and analyzed by Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23. Descriptive and inferential statistics were performed. Adjusted odds ratio with 95 % confidence interval were used to identify the significance of the association between the level of knowledge on preeclampsia and its predictors. Results: In this study, 118 (28.8 %), 120 (29.3 %) of the study participants had good knowledge and a positive attitude towards preeclampsia respectively. The likelihood of having good knowledge on preeclampsia was found to be low among women with no education (AOR = 0.22, 95 % CI (0.06, 0.85)), one antenatal care visit (ANC) (AOR = 0.13, 95 % CI (0.03, 0.59)). -

International Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatal Health

Prevalence and associated factors of Neonatal near miss among Neonates Born in Hospitals at South Gondar Zone Amhara Region, North West Ethiopia, 2020 International Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatal Health Research Article Volume 5 Issue 1, Prevalence and associated factors of Neonatal near miss among January 2021 Neonates Born in Hospitals at South Gondar Zone Amhara Region, North West Ethiopia, 2020 Copyright ©2021 Adnan Baddour et al. Enyew Dagnew*, Habtamu Geberehana, Minale Bezie, and Abenezer Melkie This is an open access article distributed under the terms of Debre Tabor University, College of Health Sciences, Debre Tabor, Ethiopia the Creative Commons Attri- bution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, Corresponding author: Enyew Dagnew and reproduction in any me- Debre Tabor University, College of Health Sciences, Debre Tabor, Ethiopia. Tel No: 0918321285, dium, provided the original E-mail: [email protected] author andsource are credited. Article History: Received: February 07, 2020; Accepted: February 24, 2020; Published: January 18, 2021. Citation Abstract Enyew Dagnew et al. (2021), Objective: The aim of this study was to determine prevalence and associated factors of neonatal near Features of Bone Mineraliza- miss in Hospitals at South Gondar Zone Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019. tion in Children with Chron- Institutional based cross sectional study was employed among 848 study participants. Data was ic Diseases. Int J Ped & Neo collected with pretested structured questionnaire. The data was entered by Epi-Info version 7 software Heal. 5:1, 10-18 and exported to SPSS version 23 for analysis. Statistical significance was declared at P value of < 0.05. Results: In this study, prevalence of neonatal near miss in the study area were 242 (28.54%) of neonates (95% CI 25.5%, 31.8%). -

Measles Outbreak in Simada District, South Gondar Zone, Amhara

Brief communication Measles outbreak in Simada District, South Gondar Zone, Amhara Region, May - June 2009: Immediate need for strengthened routine and supplemental immunization activities (SIAs) Mer’Awi Aragaw1, Tesfaye Tilay2 Abstract Background: Recently measles outbreaks have been occurring in several areas of Ethiopia. Methods: Desk review of outbreak surveillance data was conducted to identify the susceptible subjects and highly affected groups of the community in Simada District, Amhara Region, May and June, 2009. Results: A total of 97 cases with 13 deaths (Case fatality Rate (CFR) of 13.4%) were reported delayed about 2 weeks. Cases ranged in of age range from 3 months to 79 years, with 43.3% aged 15 years and above; and high age specific attack rate in children under 5 and infants (p-value<0.0001). Conclusion and Recommendation: These findings indicate accumulation of susceptible children under 5 and a need to strengthen both routine and supplemental immunization activities (SIAs) and surveillance, with monitoring of accumulation of susceptible individuals to protect both target and non-target age groups. Surveillance should be extended to and owned by volunteer community health workers and the community, particularly in such remote areas. [Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 2012;26(2):115-118] Introduction outbreaks indicate accumulation of susceptible Measles is a highly infectious viral disease that can cause population for different reasons. permanent disabilities and death. In 1980, before the widespread global use of measles vaccine, an estimated Measles outbreak was reported from Simada District on 2.6 million measles deaths occurred worldwide (1). In 29 May 2009. This study to describes the outbreak and developing countries, serious complications may occur in identifies the susceptible population. -

Technological Gaps of Agricultural Extension: Mismatch Between Demand and Supply in North Gondar Zone, Ethiopia

Vol.10(8), pp. 144-149, August 2018 DOI: 10.5897/JAERD2018.0954 Articles Number: 0B0314557914 ISSN: 2141-2170 Copyright ©2018 Journal of Agricultural Extension and Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/JAERD Rural Development Full Length Research Paper Technological gaps of agricultural extension: Mismatch between demand and supply in North Gondar Zone, Ethiopia Genanew Agitew1*, Sisay Yehuala1, Asegid Demissie2 and Abebe Dagnew3 1Department of Rural Development and Agricultural Extension, College of Agriculture and Rural Transformation, University of Gondar, Ethiopia. 2College of Business and Economics, University of Gondar, Ethiopia. 3Departments of Agricultural Economics, College of Agriculture and Rural Transformation, University of Gondar, Ethiopia. Received 27 March, 2018; Accepted 30 April, 2018 This paper examines technological challenges of the agricultural extension in North Gondar Zone of Ethiopia. Understanding technological gaps in public agricultural extension helps to devise demand driven and compatible technologies to existing contexts of farmers. The study used cross sectional survey using quantitative and qualitative techniques. Data were generated from primary and secondary sources using household survey from randomly taken households, focus group discussions, key informant interview, observation and review of relevant documents and empirical works. The result of study shows that there are mismatches between needs of smallholders in crop and livestock production and available agricultural technologies delivered by public agricultural extension system. The existing agricultural technologies are limited and unable to meet the diverse needs of farm households. On the other hand, some of agricultural technologies in place are not appropriate to existing context because of top-down recommendations than need based innovation approaches. -

Phenotypic Characterization of Indigenous Chicken Ecotypes in North Gondar Zone, Ethiopia

Global Veterinaria 12 (3): 361-368, 2014 ISSN 1992-6197 © IDOSI Publications, 2014 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.gv.2014.12.03.76136 Phenotypic Characterization of Indigenous Chicken Ecotypes in North Gondar Zone, Ethiopia 12Addis Getu, Kefyalew Alemayehu and 3Zewdu Wuletaw 1University of Gondar, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Animal Production and Extension 2Bahir Dar University College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, Department of Animal Production and Technology 3Sustainable Land Management Organization (SLM) Bihar Dar, Ethiopia Abstract: An exploratory field survey was conducted in north Gondar zone, Ethiopia to identify and characterize the local chicken ecotypes. Seven qualitative and twelve quantitative traits from 450 chickens were considered. Chicken ecotypes such as necked neck, Gasgie and Gugut from Quara, Alefa and Tache Armacheho districts were identified, respectively. Morphometric measurements indicated that the body weight and body length of necked neck and Gasgie ecotypes were significantly (p < 0.01) higher than Gugut ecotypes except in shank circumstances. Sex and ecotype were the significant (p < 0.01) sources of variation for both body weights and linear body measurements. The relationship of body weight with other body measurements for all ecotypes in both sexes were highly significant (r = 0.67, p < 0.01). Some traits like wingspan, body length and super length (r = 0.64, P < 0.01) for males and for females (r = 0.59, P < 0.01) of necked neck chickens are significantly correlated with body weight. Therefore, highly correlated traits are the basic indicators for estimation of the continuous prediction of body weight of chicken. Identification and characterization of new genetic resources should be employed routinely to validate and investigate the resources in the country. -

Modeling Malaria Cases Associated with Environmental Risk Factors in Ethiopia Using Geographically Weighted Regression

MODELING MALARIA CASES ASSOCIATED WITH ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS IN ETHIOPIA USING GEOGRAPHICALLY WEIGHTED REGRESSION Berhanu Berga Dadi i MODELING MALARIA CASES ASSOCIATED WITH ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS IN ETHIOPIA USING THE GEOGRAPHICALLY WEIGHTED REGRESSION MODEL, 2015-2016 Dissertation supervised by Dr.Jorge Mateu Mahiques,PhD Professor, Department of Mathematics University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain Ana Cristina Costa, PhD Professor, Nova Information Management School University of Nova Lisbon, Portugal Pablo Juan Verdoy, PhD Professor, Department of Mathematics University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain March 2020 ii DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that the work described in this document is my own and not from someone else. All the assistance I have received from other people is duly acknowledged, and all the sources (published or not published) referenced. This work has not been previously evaluated or submitted to the University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain, or elsewhere. Castellon, 30th Feburaury 2020 Berhanu Berga Dadi iii Acknowledgments Before and above anything, I want to thank our Lord Jesus Christ, Son of GOD, for his blessing and protection to all of us to live. I want to thank also all consortium of Erasmus Mundus Master's program in Geospatial Technologies for their financial and material support during all period of my study. Grateful acknowledgment expressed to Supervisors: Prof.Dr.Jorge Mateu Mahiques, Universitat Jaume I(UJI), Prof.Dr.Ana Cristina Costa, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, and Prof.Dr.Pablo Juan Verdoy, Universitat Jaume I(UJI) for their immense support, outstanding guidance, encouragement and helpful comments throughout my thesis work. Finally, but not least, I would like to thank my lovely wife, Workababa Bekele, and beloved daughter Loise Berhanu and son Nethan Berhanu for their patience, inspiration, and understanding during the entire period of my study. -

Ethiopia Final Evaluation Report

ETHIOPIA: Mid-Term Evaluation of UNCDF’s Local Development Programme Submitted to: United Nations Capital Development Fund Final Evaluation Report 23 July 2007 Prepared by: Maple Place North Woodmead Business Park 145 Western Service Road Woodmead 2148 Tel: +2711 802 0015 Fax: +2711 802 1060 www.eciafrica.com UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT FUND EVALUATION REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. PROJECT SUMMARY 1 2. PURPOSE OF THE EVALUATION 2 Purpose of the evaluation 2 Programme Cycle 2 3. EVALUATION METHODOLOGY 3 Methodology and tools used 3 Work plan 4 Team composition 5 4. PROGRAMME PROFILE 6 Understanding the context 6 Donor Interventions in Amhara Region 7 Programme Summary 8 Programme Status 9 5. KEY EVALUATION FINDINGS 13 Results achievement 13 Sustainability of results 21 Factors affecting successful implementation & results achievement 24 External Factors 24 Programme related factors 24 Strategic position and partnerships 26 Future UNCDF role 27 6. LESSONS 28 Programme-level lessons 28 7. RECOMMENDATIONS 29 Results achievement 29 Sustainability of results 29 Factors affecting successful implementation and results achievement 30 Strategic positioning and partnerships 31 Future UNCDF role 31 “The analysis and recommendations of this report do not necessarily reflect the view of the United Nations Capital Development Fund, its Executive Board or the United Nations Member States. This is an independent publication of UNCDF and reflects the views of its authors” PREPARED BY ECIAFRICA CONSULTING (PTY) LTD, PROPRIETARY AND CONFIDENTIAL i 2007/05/24 -

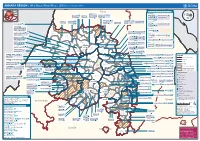

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

Preservice Laboratory Education Strengthening Enhances

Fonjungo et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, 11:56 http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/11/1/56 RESEARCH Open Access Preservice laboratory education strengthening enhances sustainable laboratory workforce in Ethiopia Peter N Fonjungo1,8*, Yenew Kebede1, Wendy Arneson2, Derese Tefera1, Kedir Yimer1, Samuel Kinde3, Meseret Alem4, Waqtola Cheneke5, Habtamu Mitiku6, Endale Tadesse7, Aster Tsegaye3 and Thomas Kenyon1 Abstract Background: There is a severe healthcare workforce shortage in sub Saharan Africa, which threatens achieving the Millennium Development Goals and attaining an AIDS-free generation. The strength of a healthcare system depends on the skills, competencies, values and availability of its workforce. A well-trained and competent laboratory technologist ensures accurate and reliable results for use in prevention, diagnosis, care and treatment of diseases. Methods: An assessment of existing preservice education of five medical laboratory schools, followed by remedial intervention and monitoring was conducted. The remedial interventions included 1) standardizing curriculum and implementation; 2) training faculty staff on pedagogical methods and quality management systems; 3) providing teaching materials; and 4) procuring equipment for teaching laboratories to provide practical skills to complement didactic education. Results: A total of 2,230 undergraduate students from the five universities benefitted from the standardized curriculum. University of Gondar accounted for 252 of 2,230 (11.3%) of the students, Addis Ababa University for 663 (29.7%), Jimma University for 649 (29.1%), Haramaya University for 429 (19.2%) and Hawassa University for 237 (10.6%) of the students. Together the universities graduated 388 and 312 laboratory technologists in 2010/2011 and 2011/2012 academic year, respectively. -

Transhumance Cattle Production System in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is It Sustainable?

WP14_Cover.pdf 2/12/2009 2:21:51 PM www.ipms-ethiopia.org Working Paper No. 14 Transhumance cattle production system in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is it sustainable? C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Transhumance cattle production system in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is it sustainable? Azage Tegegne,* Tesfaye Mengistie, Tesfaye Desalew, Worku Teka and Eshete Dejen Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia * Corresponding author: [email protected] Authors’ affiliations Azage Tegegne, Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Tesfaye Mengistie, Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia Tesfaye Desalew, Kutaber woreda Office of Agriculture and Rural Development, Kutaber, South Wello Zone, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia Worku Teka, Research and Development Officer, Metema, Amhara Region, Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Eshete Dejen, Amhara Regional Agricultural Research Institute (ARARI), P.O. Box 527, Bahir Dar, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia © 2009 ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute). All rights reserved. Parts of this publication may be reproduced for non-commercial use provided that such reproduction shall be subject to acknowledgement of ILRI as holder of copyright. Editing, design and layout—ILRI Publications Unit, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Correct citation: Azage Tegegne, Tesfaye Mengistie, Tesfaye Desalew, Worku Teka and Eshete Dejen. 2009. Transhumance cattle production system in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is it sustainable? IPMS (Improving Productivity and Market Success) of Ethiopian Farmers Project. -

Ethiopia Round 6 SDP Questionnaire

Ethiopia Round 6 SDP Questionnaire Always 001a. Your name: [NAME] Is this your name? ◯ Yes ◯ No 001b. Enter your name below. 001a = 0 Please record your name 002a = 0 Day: 002b. Record the correct date and time. Month: Year: ◯ TIGRAY ◯ AFAR ◯ AMHARA ◯ OROMIYA ◯ SOMALIE BENISHANGUL GUMZ 003a. Region ◯ ◯ S.N.N.P ◯ GAMBELA ◯ HARARI ◯ ADDIS ABABA ◯ DIRE DAWA filter_list=${this_country} ◯ NORTH WEST TIGRAY ◯ CENTRAL TIGRAY ◯ EASTERN TIGRAY ◯ SOUTHERN TIGRAY ◯ WESTERN TIGRAY ◯ MEKELE TOWN SPECIAL ◯ ZONE 1 ◯ ZONE 2 ◯ ZONE 3 ZONE 5 003b. Zone ◯ ◯ NORTH GONDAR ◯ SOUTH GONDAR ◯ NORTH WELLO ◯ SOUTH WELLO ◯ NORTH SHEWA ◯ EAST GOJAM ◯ WEST GOJAM ◯ WAG HIMRA ◯ AWI ◯ OROMIYA 1 ◯ BAHIR DAR SPECIAL ◯ WEST WELLEGA ◯ EAST WELLEGA ◯ ILU ABA BORA ◯ JIMMA ◯ WEST SHEWA ◯ NORTH SHEWA ◯ EAST SHEWA ◯ ARSI ◯ WEST HARARGE ◯ EAST HARARGE ◯ BALE ◯ SOUTH WEST SHEWA ◯ GUJI ◯ ADAMA SPECIAL ◯ WEST ARSI ◯ KELEM WELLEGA ◯ HORO GUDRU WELLEGA ◯ Shinile ◯ Jijiga ◯ Liben ◯ METEKEL ◯ ASOSA ◯ PAWE SPECIAL ◯ GURAGE ◯ HADIYA ◯ KEMBATA TIBARO ◯ SIDAMA ◯ GEDEO ◯ WOLAYITA ◯ SOUTH OMO ◯ SHEKA ◯ KEFA ◯ GAMO GOFA ◯ BENCH MAJI ◯ AMARO SPECIAL ◯ DAWURO ◯ SILTIE ◯ ALABA SPECIAL ◯ HAWASSA CITY ADMINISTRATION ◯ AGNEWAK ◯ MEJENGER ◯ HARARI ◯ AKAKI KALITY ◯ NEFAS SILK-LAFTO ◯ KOLFE KERANIYO 2 ◯ GULELE ◯ LIDETA ◯ KIRKOS-SUB CITY ◯ ARADA ◯ ADDIS KETEMA ◯ YEKA ◯ BOLE ◯ DIRE DAWA filter_list=${level1} ◯ TAHTAY ADIYABO ◯ MEDEBAY ZANA ◯ TSELEMTI ◯ SHIRE ENIDASILASE/TOWN/ ◯ AHIFEROM ◯ ADWA ◯ TAHTAY MAYCHEW ◯ NADER ADET ◯ DEGUA TEMBEN ◯ ABIYI ADI/TOWN/ ◯ ADWA/TOWN/ ◯ AXUM/TOWN/ ◯ SAESI TSADAMBA ◯ KLITE