Effectiveness of Fear and Crime Prevention Strategy For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flusim Simulation for Malaysia: Towards Improved Pandemic Surveillance

International Journal of Chemical Engineering and Applications, Vol. 2, No. 1, February 2011 ISSN: 2010-0221 FluSiM Simulation for Malaysia: Towards Improved Pandemic Surveillance Hock Lye Koh and Su Yean Teh 1968, about 43 years ago. Based upon this statistics it is not Abstract— The A H1N1 2009 influenza that started in Mexico surprising that WHO is concerned that the A H1N1 2009 in early April 2009 ultimately spread over the entire globe might evolve into the next pandemic. within a matter of a few months. Malaysia reported its first The A H1N1 2009 influenza that started in Mexico in confirmed A H1N1 2009 infection on 15 May 2009. The April 2009 [2] ultimately spread to Malaysia. For Malaysia, infection persisted for 23 weeks, peaking at week 12, with a total of about thirteen thousand infections, with residual infections Fig. 1 shows the number of H1N1 weekly infections reported continuing until today. Many countries are concerned over the in Malaysia from week 22 of 2009 to week 11 of 2010, potential of a more severe second wave of H1N1 and have put in available from the Malaysian Ministry of Health (MOH), place contingency plan to mitigate this H1N1 threats should with the first case confirmed on 15 May 2009. The bell-shape they occur. This paper presents the model FluSiM developed to infection curve strongly suggests that the A H1N1 infections simulate A H1N1 2009 in Malaysia. Simulation results for H1N1 can be modeled by the well-known SIR model. Details 2009 in Malaysia indicate that the basic reproduction number varied between 1.5 and 2.5. -

Kuala Lumpur, Melaka & Penang

Plan Your Trip 12 ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Kuala Lumpur, Melaka & Penang “All you’ve got to do is decide to go and the hardest part is over. So go!” TONY WHEELER, COFOUNDER – LONELY PLANET THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Simon Richmond, Isabel Albiston Contents PlanPlan Your Your Trip Trip page 1 4 Welcome to Top Itineraries ...............16 Eating ............................25 Kuala Lumpur ................. 4 If You Like... ....................18 Drinking & Nightlife.... 31 Kuala Lumpur’s Top 10 ...6 Month By Month ........... 20 Entertainment ............ 34 What’s New ....................13 With Kids ....................... 22 Shopping ...................... 36 Need to Know ................14 Like a Local ................... 24 Explore Kuala Lumpur 40 Neighbourhoods Masjid India, Day Trips from at a Glance ................... 42 Kampung Baru & Kuala Lumpur ............. 112 Northern KL .................. 83 Bukit Bintang Sleeping ......................124 & KLCC .......................... 44 Lake Gardens, Brickfields & Bangsar .. 92 Melaka City.................133 Chinatown, Merdeka Square & Bukit Nanas ...67 Penang .........................155 Understand Kuala Lumpur 185 Kuala Lumpur Life in Kuala Lumpur ...197 Arts & Architecture .... 207 Today ........................... 186 Multiculturalism, Environment ................212 History ......................... 188 Religion & Culture ......200 Survival Guide 217 Transport .....................218 Directory A–Z ............. 222 Language ....................229 Kuala -

I. the Royal Malaysia Police

HUMAN RIGHTS “No Answers, No Apology” Police Abuses and Accountability in Malaysia WATCH “No Answers, No Apology” Police Abuses and Accountability in Malaysia Copyright © 2014 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-1173 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2014 ISBN: 978-1-62313-1173 “No Answers, No Apology” Police Abuses and Accountability in Malaysia Glossary .......................................................................................................................... 1 Map of Malaysia ............................................................................................................. -

15) the Effects of Microcredit Access and Macroeconomic Conditions On

Int. Journal of Economics and Management 12 (1): 285-304 (2018) IJEM International Journal of Economics and Management Journal homepage: http://www.ijem.upm.edu.my THE EFFECTS OF MICROCREDIT ACCESS AND MACROECONOMIC CONDITIONS ON LOWER INCOME GROUP THILAGARANI SELVARAJA*, ZULKEFLY ABDUL KARIMA, AISYAH ABDUL-RAHMANA AND NORSHAMLIZA CHAMHURIA AFaculty Economics and Management, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia ABSTRACT This paper examines the impact of the microcredit access and macroeconomic conditions on the headcount of lower income group. By identifying the determinants that contribute to the successful impact can make the microcredit organization’s evaluation more strategic and efficient that can leads to outgrow of the lower income group (proxy by Bottom 40 Headcounts) and move-up to the middle-income group. The study utilizes the panel data (fixed effect analysis) of 16-states and federal territories (Malaysia) from the year 2011 to 2015. Based on the overall findings of this study, it is crucial to analyze the impact from the microcredit access and macroeconomic condition on the headcount of lower income group. The study reveals that the number of loans per microcredit office has significant positive effect on lower income group headcount. The numbers of borrowings from the agriculture sector and female to male ratio borrowings have significant negative effect on the headcount of lower income group. The finding implies that the female has a higher tendency towards reducing the headcount of lower income group. Additionally the general macroeconomic condition also influences significantly the lower income group, as this group is vulnerable to economic shocks. This paper will contribute to the existing microcredit studies in the following dimension namely implications for academic, microfinance institutions and policymakers. -

Barriers to Mobility

An Overview of Research and Factsheets #mymobilitymatters 1 BARRIERS cover TO WOMEN’S MOBILITY An Overview of Research and Factsheet s #MYMOBILITYMATTERS An Overview of Research and Factsheets #mymobilitymatters 2 CONTENTS 02 04 PREFACE AHRC RESEARCH TEAM 05 WOMEN’S MOBILITY 06 08 STATISTICS RELATED TO CRIME CASES WOMEN 10 FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSION 16 20 QUESTIONNAIRE SURVEY SHARING DISCUSSION 23 CONCLUSION www.womenmobility.com An Overview of Research and Factsheets #mymobilitymatters 3 The research entitled “Barriers to Women’s AHRC Mobility” intended to explore the struggle and barriers of women while travelling and RESEARCH basically addressing two of the UN’s Global Goals for Sustainable Development TEAM It is a network project for the research team to acquire first-hand knowledge of UNITED KINGDOM COVENTRY UNIVERSITY the problems women experience in PROF DR. ANDREE accessing transport and analyse the existing WOODCOOK solutions and their effectiveness in UNIVERISITY OF ILLINOIS Pakistan, Malaysia and the UK DR. DEANA CATHERINE MCDONAGH PAKISTAN (DESIGNPAK) KOMAL FAIZ PUNNAL FAIZ MALAYSIA UNIVERSITY MALAYA DR YONG ADILAH SHAMSUL HARUMAIN DR NIKMATUL ADHA DR GOH HONG CHING DR NOOR SUZAINI RESEARCH ASSISTANT MIRAWAHIDA LEE WEI SAN NETWORK RESEARCH SUHANA MUSTAFA AHMAD AL-RASHID An Overview of Research and Factsheets #mymobilitymatters 4 However, it is not equally accessible for every WOMEN’S individual in benefiting from the advanced transport system due to differences need. Mobility on public transportation is focused as it MOBILITY has increasingly become a societal concern nowadays. There is growing mobility literature on It has been long recognized the importance of the gender differences in mobility development of transport system, not only in enabling individuals to travel further and faster to In the study on the choice of destinations but also have a greater transportation, mobility is societal and economic impacts globally to create a defined as the movement of more sustainable living world. -

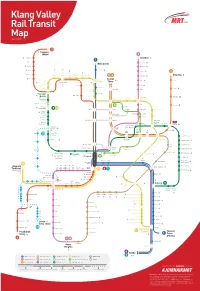

Klang Valley Rail Transit Map April 2020

Klang Valley Rail Transit Map April 2020 2 P Tanjung Malim 5 P Kuala Kubu Baru Gombak P 1 P Rasa Taman Melati P Batu Caves P Batang Kali Wangsa Maju P P P P Serendah Taman Wahyu P P Sri Rampai P 3 Sri Sri P Metro P Rawang Damansara Damansara Kepong Sri Prima Ampang P Sentral Timur Baru Jinjang Delima 4 3 Setiawangsa P P Kuang Sentul Cahaya Kampung P Jelatek P Sri Batu P Timur P Damansara Kepong Sentral P Barat P Kentonmen Dato’ Keramat Kepong Damansara Batu Kentomen Damai Cempaka P Sentul P Jalan Damai Ipoh *Sungai Sentul P P P Segambut Sentul Buloh Pandan Indah P Barat Hospital Raja Ampang *Kampung Titiwangsa Kuala Lumpur Uda Park Selamat *Rubber Research Institute 8 KLCC Pandan Jaya P *Kwasa Chow Kit P Damansara 9 12 Putra PWTC Medan Tuanku Kampung Baru Persiaran KLCC Kwasa P Sentral Sultan Ismail Dang Wangi Bukit Nanas Kota Conlay Damansara Raja Chulan Surian Bank Negara Bandaraya Tun Razak Mutiara Exchange (TRX) Damansara Bukit Bintang Cochrane Maluri P Bandar Bukit Bintang P Masjid Utama Jamek Imbi S01 P Miharja P Plaza Hang Rakyat Tuah Pudu S02 Taman Tun 11 Dr Ismail Taman Pertama Chan Phileo P Merdeka Sow Lin Damansara Taman Midah P S03 P Kuala Lumpur Cheras Taman Mutiara Bukit Kiara Bandar Malaysia P Muzium Negara Pasar Utara Seni Maharajalela Taman Connaught S04 Salak Selatan P KL Sentral P Bandar Malaysia Taman Suntex Selatan P P Tun Sambanthan Semantan KL Sentral 8 Pusat Bandar Sri Raya P S05 Damansara P Mid Valley Seputeh Salak Selatan Bandar Tun Bandar Tun Razak P Hussein Onn 10 Bangsar P P P P P S06 Batu 11 Cheras Skypark -

KUALA LUMPUR Your Free Copy ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

www.facebook.com/friendofmalaysia twitter.com/tourismmalaysia Published by Tourism Malaysia, Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Malaysia KUALA LUMPUR Your Free Copy ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in The Dazzling Capital City whole or part without the written permission of the publisher. While every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is correct at the time of publication, Tourism Malaysia shall not be held liable for any errors, omissions or inaccuracies which may occur. KL (English) / IH / PS April 2015 (0415) (TRAFFICKING IN ILLEGAL DRUGS CARRIES THE DEATH PENALTY) 1 CONTENTS 4 DOING THE SIGHTS 38 SENSATIONAL SHOPPING 5 Prestigious Landmarks 39 Shopping Malls 6 Heritage Sites 42 Craft Centres 10 Places of Worship 43 Street Markets and Bazaars 12 Themed Attractions 44 Popular Malaysian Souvenirs 14 TROPICAL ENCLAVES 45 EATING OUT 15 Perdana Botanical Gardens 46 Malay Cuisine 16 KLCC Park 46 Chinese Cuisine 17 Titiwangsa Lake Gardens 46 Indian Cuisine 17 National Zoo 46 Mamak Cuisine 17 Bukit Nanas Forest Reserve 47 International Cuisine 47 Malaysian Favourites 18 TREASURE TROVES 49 Popular Restaurants in KL 19 Museums 21 Galleries 52 BEYOND THE CITY 22 Memorials 53 Kuala Selangor Fireflies 53 Batu Caves 23 RELAX AND REJUVENATE 53 Forest Research Institute of Malaysia 24 Spa Retreats (FRIM) 25 Healthcare 54 Putrajaya 54 Port Dickson 26 ENTHRALLING PERFORMANCES 54 Genting Highlands 27 Premier Concert Halls 55 Berjaya Hills 27 Cultural Shows 55 Cameron Highlands 28 Fine Arts Centres 55 Melaka 29 CELEBRATIONS GALORE 56 USEFUL INFORMATION 30 Religious Festivals 57 Accommodation 31 Events and Celebrations 61 Getting There 62 Getting Around 33 ENTERTAINMENT AND 65 Useful Contacts EXCITEMENT 66 Malaysia at a Glance 34 Theme Parks 67 Saying it in Malay 35 Sports and Recreation 68 Map of Kuala Lumpur 37 Nightlife 70 Tourism Malaysia Offices 2 Welcome to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia’s dazzling capital city Kuala Lumpur or KL is a modern metropolis amidst colourful cultures. -

Issues Regarding the Design Intervention and Conservation of Heritage Areas: the Historical Pedestrian Streets of Kuala Lumpur

sustainability Article Issues Regarding the Design Intervention and Conservation of Heritage Areas: The Historical Pedestrian Streets of Kuala Lumpur Ahmed Bindajam 1, Fadrul Hisham 2, Nashwan Al-Ansi 3 and Javed Mallick 4,* 1 Department of Architecture and Planning, College of Engineering, King Khalid University, Abha 61411, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Design and Architecture, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Seri Kembangan 43400, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Architecture and Planning, Qassim University, Al Qassim 51452, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 4 Department of Civil Engineering, College of Engineering, King Khalid University, Abha 61411, Saudi Arabia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +966-172-428-439; Fax: +966-172-418-152 Received: 17 April 2020; Accepted: 6 May 2020; Published: 14 May 2020 Abstract: This study focused on the areas of Petaling Street and Jalan Hang Kasturi, Kuala Lumpur, in a historical enclave that is well known locally for its cultural, architectural, and historical interest that is worth preserving and conserving. To fulfill the purpose of enhancing the areas, the local authority introduced a covered pedestrian street, which is said to be more convenient for shoppers, considering the tropical climate of Kuala Lumpur. This effort is believed to have been done without any consultation with heritage conservators and activists, thus invoking a debate regarding its many pros and cons. This study examined the arguments concerning the intervention in the heritage area from various groups of stakeholders that are directly involved. Furthermore, this paper presents the method of implementation used by the local authority when executing a conservation project. -

Malaysia Real Estate Highlights

A comprehensive analysis of Malaysia's residential, retail, office and industrial markets Real Estate Highlights knightfrank.com/research Research, 1st Half 2020 REAL ESTATE HIGHLIGHTS KUALA LUMPUR HIGH END CONDOMINIUM MARKET Market Indications Highlights The COVID-19 pandemic is driving the global economy into recession and many countries, including Malaysia, are responding with stimulus packages to avoid a cascade of bankruptcies and emerging market debt defaults. The country’s dependency on oil revenue The recovery path of the property will further strain the government’s fiscal position amid declining oil prices. market since 2019, which was supported by the extended Home The country’s economy expanded 4.3% in 2019 (2018: 4.7%), the lowest growth since the Ownership Campaign (HOC), has global financial crisis in 2009. It weakened further to record at 0.7% in 1Q2020 (4Q2019: been thrown off by the onset of the 3.6%), reflecting the early impact of measures taken both globally and domestically to COVID-19 pandemic in 1Q2020. contain the spread of the novel coronavirus. Malaysia's economic growth for 2020, as measured by gross domestic product (GDP), is projected at between -2.0% and 0.5%. 6-month automatic loan moratorium to provide a short-term breather to The period of low headline inflation, recorded at 0.7% in 2019 (2018: 1.0%), mainly reflects borrowers impacted by the pandemic. the lapse in the impact from the Sales and Services Tax (SST) implementation. It continued to remain modest at 0.9% in 1Q2020 (4Q2019: 1.0%) due to lower fuel costs. The country’s The Central Bank has also lowered average headline inflation for 2020 is expected to turn negative due to lower global fuel the Overnight Policy Rate (OPR) thrice prices coupled with weaker domestic growth prospects and labour market conditions. -

Press Statement Malaysian Anti- Corruption Commission

Address :Strategic Communication Division Level 18, Block C, Head Quarters Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission, No. 2, Lebuh Wawasan, Presint 7, 62250 Putrajaya Tel. : 03-8870 0015 PRESS STATEMENT Fax : 03-8870 0908 Email : [email protected] Web : www.sprm.gov.my MALAYSIAN ANTI - Twitter : twitter.com/SPRMMalaysia Facebook: facebook.com/sprm.benci.rasuah Blog : www.ourdifferentview.com CORRUPTION Youtube : www.youtube.com/odvmacc COMMISSION ‘Walk Stop Talk: Six Hours Quarter Million Messages’ Spread Anti-Corruption Messages Through Future Educators THE Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) in collaboration with the Institute of Teacher Education (IPGM) and the Kuala Lumpur City Hall (DBKL) had organized the 'Walk Stop Talk: Six Hours Quarter Million Messages' event to spread corruption prevention message to the general public in country. A total of 1,000 participants including MACC officers and educators from 27 IPGM campuses will move simultaneously to 262 locations across the country beginning at 9 am to 3 pm to meet the public and distribute 250,000 brochures with anti-corruption messages and get the public’s signatures to support the initiative to fight against corruption. In order to record the success of this program in The Malaysia Book of Record and to receive the certification, the organizer should get a quarter million signatures of the community to fight against corruption. The closing ceremony of the ‘Walk Stop Talk: Six Hours Quarter Million Messages’ program was completed by the Deputy Prime Minister, Datuk Seri Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, accompanied by MACC Chief Commissioner, Dato’ Sri Mohd. Shukri Abdull at the Kuala Lumpur City Hall Field (DBKL), today. -

Download Brochure

FREEHOLD REINVENTING COMMUNITIES Artist’s Impression AN ALL INCLUSIVE COMMUNITY The Suite is the most exciting and Inviting you to be amongst a anticipated co-living and co-working community of like-minded people, space in Kuala Lumpur. In today’s fast one that shares your values in paced digital world, urban dwellers defining the perfect hybrid and knowledge entrepreneurs home-office experience, demand enhanced ways of living, here at The Suite. entertaining, working and interacting. CO-WORKING The latest buzzword in reinventing the concept of traditional offices into one that adds the flexibility and comforts of your space. Whether working as an individual or as a collaboration, The Suite completes COMMUNITY LIFESTYLE your needs in a home and workspace, The Suite sits quietly within an all in one place, complete with all the enclave, just one street off the right trimmings. international offerings of Jalan Ampang. SUITE DREAMS ARE MADE OF THESE The perfect place to live, a definition that evolves through time. Changing based on progress, trends and needs, which come about with modernity. The Suite checks all four boxes that matter now, in order to achieve this new hybrid living concept with success. CO-LIVING SHARED SPACES The Suite gathers like-minded Shared facilities, conveniences urbanites who have a mutual and services allow for much need for convenience, access, more to be offered to the entertainment and rejuvenation. urbanites and entrepreneurs here. Now we are able to cater Satisfy your lifestyle with a to a wider range of lifestyles, host of experiences offered, appetites and interests. or simply retire in the privacy of your living space for some alone time, whenever you need. -

Seri Negara Are Both Registered As Heritage Building

EP 2 FRIDAY SEPTEMBER 21, 2018 • THEEDGE FINANCIAL DAILY NEWS HIGHLIGHTS from www.EdgeProp.my Taman Midah folk want City Hall to Draft Penang Structure Plan 2030 halt development on green lung displayed for public feedback Residents in Taman Midah, Cheras, Kuala Lumpur want the authorities The draft of the Penang Structure to be “collated, scrutinised and to halt a mixed-use development on Plan 2030 (PSP 2030) is currently considered”, said state housing, a green lung in their area. on display for two months starting town, country planning and local They have been complaining on Sept 18 at Level Three, Komtar, government committee chairman about the proposed development Penang Island and at the Seberang Jagdeep Singh Deo. since last year and they now hope Perai Municipal Council (MPSP) on The PSP 2030 is an update of the new administration in both Pu- the mainland. the PSP 2020 which was gazetted trajaya and Kuala Lumpur City Hall The public display period which in 2007, and serves to determine (DBKL) will now heed their cries for is twice the time period required by the type of development projects the project to be stopped. law will enable the state govern- allowed in Penang as well as out- News reports described the pro- ment to receive even more feed- line its development plans until ject as comprising two 50-storey back, suggestions and critiques 2030. office blocks on a 0.975 ha land. The Edge Property Sdn Bhd (1091814-P) There will also be 1,319 apartment Level 3, Menara KLK, units and an eight-storey car park.