Digital Elevation Model Quality Assessment Methods: a Critical Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hirise Digital Elevation Model of Phobos: Implications for Morphological Analysis of Grooves

50th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2019 (LPI Contrib. No. 2132) 1759.pdf HIRISE DIGITAL ELEVATION MODEL OF PHOBOS: IMPLICATIONS FOR MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF GROOVES. R. Hemmi1 and H. Miyamoto2, 1The University Museum, The University of Tokyo (7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, 113-0033, Japan, [email protected]), 2Depatment of Systems Inno- vation, School of Engineering, The University of Tokyo Introduction: Linear narrow depressions common- ly known as “grooves,” can be observed on a variety of small bodies including Phobos, Gaspra, Ida, Eros, and small saturnian satellites [1]. Characteristics of grooves may reflect geological events, inherent in individual bodies. The surface of Phobos is mostly covered by grooves many of which are less than ~1 km wide. It remains controversial whether their morphologies rep- resent past internal (e.g., tidal disruption [2]) or exter- nal processes (e.g., crater chains [3,4], rolling boulders [5], etc.). The presence of raised rims on grooves is an important diagnostic of impact cratering processes as opposed to extensional stress which would form rim- less depressions [6]. Groove rims were previously identified from images [6–8]; however, their detailed topographies have not been well investigated. This is primarily due to limited spatial resolutions of previous digital terrain models (up to 100 meters) which are similar to the widths of target features (a few hundreds Fig. 1. HiRISE stereo pair images of Phobos (upper of meters). In this study, we produce a digital elevation images) and a part of HRSC global orthomosaic (lower model (DEM) from Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s image) with ground control points (magenta crosses). -

A Brief Guide

CHAPTER 1 Geomorphometry: A Brief Guide R.J. Pike, I.S. Evans and T. Hengl basic definitions · the land surface · land-surface parameters and objects · digital elevation models (DEMs) · basic principles of geomorphometry from a GIS perspective · inputs/outputs, data structures & algorithms · history of geomorphometry · geomorphometry today · data set used in this book 1. WHAT IS GEOMORPHOMETRY? Geomorphometry is the science of quantitative land-surface analysis (Pike, 1995, 2000a; Rasemann et al., 2004). It is a modern, analytical-cartographic approach to rep- resenting bare-earth topography by the computer manipulation of terrain height (Tobler, 1976, 2000). Geomorphometry is an interdisciplinary field that has evolved from mathematics, the Earth sciences, and — most recently — computer science (Figure 1). Although geomorphometry1 has been regarded as an activity within more established fields, ranging from geography and geomorphology to soil sci- ence and military engineering, it is no longer just a collection of numerical tech- niques but a discipline in its own right (Pike, 1995). It is well to keep in mind the two overarching modes of geomorphometric analysis first distinguished by Evans (1972): specific, addressing discrete surface features (i.e. landforms), and general, treating the continuous land surface. The morphometry of landforms per se, by or without the use of digital data, is more correctly considered part of quantitative geomorphology (Thorn, 1988; Scheidegger, 1991; Leopold et al., 1995; Rhoads and Thorn, 1996). Geomorphometry in this book is primarily the computer characterisation and analysis of continuous topography. A fine-scale counterpart of geomorphometry in manufacturing is industrial surface metrology (Thomas, 1999; Pike, 2000b). The ground beneath our feet is universally understood to be the interface be- tween soil or bare rock and the atmosphere. -

Digital Mapping & Spatial Analysis

Digital Mapping & Spatial Analysis Zach Silvia Graduate Community of Learning Rachel Starry April 17, 2018 Andrew Tharler Workshop Agenda 1. Visualizing Spatial Data (Andrew) 2. Storytelling with Maps (Rachel) 3. Archaeological Application of GIS (Zach) CARTO ● Map, Interact, Analyze ● Example 1: Bryn Mawr dining options ● Example 2: Carpenter Carrel Project ● Example 3: Terracotta Altars from Morgantina Leaflet: A JavaScript Library http://leafletjs.com Storytelling with maps #1: OdysseyJS (CartoDB) Platform Germany’s way through the World Cup 2014 Tutorial Storytelling with maps #2: Story Maps (ArcGIS) Platform Indiana Limestone (example 1) Ancient Wonders (example 2) Mapping Spatial Data with ArcGIS - Mapping in GIS Basics - Archaeological Applications - Topographic Applications Mapping Spatial Data with ArcGIS What is GIS - Geographic Information System? A geographic information system (GIS) is a framework for gathering, managing, and analyzing data. Rooted in the science of geography, GIS integrates many types of data. It analyzes spatial location and organizes layers of information into visualizations using maps and 3D scenes. With this unique capability, GIS reveals deeper insights into spatial data, such as patterns, relationships, and situations - helping users make smarter decisions. - ESRI GIS dictionary. - ArcGIS by ESRI - industry standard, expensive, intuitive functionality, PC - Q-GIS - open source, industry standard, less than intuitive, Mac and PC - GRASS - developed by the US military, open source - AutoDESK - counterpart to AutoCAD for topography Types of Spatial Data in ArcGIS: Basics Every feature on the planet has its own unique latitude and longitude coordinates: Houses, trees, streets, archaeological finds, you! How do we collect this information? - Remote Sensing: Aerial photography, satellite imaging, LIDAR - On-site Observation: total station data, ground penetrating radar, GPS Types of Spatial Data in ArcGIS: Basics Raster vs. -

Assessing the Accuracy of Underwater Photogrammetry for Archaeology

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Assessing the Accuracy of Underwater Photogrammetry for Archaeology: A Comparison of Structure from Motion Photogrammetry and Real Time Kinematic Survey at the East Key Construction Wreck Anne E. Wright 1,* , David L. Conlin 1 and Steven M. Shope 2 1 National Park Service Submerged Resources Center, Lakewood, CO 80228, USA; [email protected] 2 Sandia Research Corporation, Mesa, AZ 85207, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 September 2020; Accepted: 19 October 2020; Published: 28 October 2020 Abstract: The National Park Service (NPS) Submerged Resources Center (SRC) documented the East Key Construction Wreck in Dry Tortugas National Park using Structure from Motion photogrammetry, traditional archaeological hand mapping, and real time kinematic GPS (Global Positioning System) survey to test the accuracy of and establish a baseline “worst case scenario” for 3D models created with NPS SRC’s tri-camera photogrammetry system, SeaArray. The data sets were compared using statistical analysis to determine accuracy and precision. Additionally, the team evaluated the amount of time and resources necessary to produce an acceptably accurate photogrammetry model that can be used for a variety of archaeological functions, including site monitoring and interpretation. Through statistical analysis, the team determined that, in the worst case scenario, in its current iteration, photogrammetry models created with SeaArray have a margin of error of 5.29 cm at a site over 84 m in length and 65 m in width. This paper discusses the design of the survey, acquisition and processing of data, analysis, issues encountered, and plans to improve the accuracy of the SeaArray photogrammetry system. -

Aerial Photogrammetry and Terrestrial (Close Range) Photogrammetry

Introduction Photogrammetry is a surveying and mapping technique which can be used in various applications. There are many uses of Photogrammetry in the surveying industry such as topographic mapping, site planning, earthwork volumes, production of digital elevation models (DEM) and orthphotography maps. It is also useful in a vast selection of industries such as architecture, manufacturing, police investigation, and even plastic surgery. The word “photogrammetry” is composed of the words “photo” and “meter” which means measurements from photographs. The classical definition of photogrammetry is: The art, science and technology of obtaining reliable information about physical objects and the environment, through processes of recording, measuring, and interpreting images on photographs. (www.state.nj.us/transportation/eng/documents/survey/Chapter7.shtm) Photogrammetry is a skilled profession for the reason that obtaining reliable measurements requires certain skills, techniques and judgments to be made by the Photogrammetrist and experience is an advantage. It is a science and technology because it takes information from an image and transforms this data into meaningful results. Types of Photogrammetry There are two types of Photogrammetry, Aerial Photogrammetry and Terrestrial (Close Range) Photogrammetry. Aerial digital photogrammetry, often used in topographical mapping, begins with digital photographs or video taken from a camera mounted on the bottom of an airplane. The plane often flies over the area in a meandering flight path so it can take overlapping photographs or video of the entire area to get complete coverage. Close-range, or terrestrial, digital photogrammetry often uses photographs taken from close proximity by hand held cameras or those mounted to a tripod. -

Chapter 13.2: Topographic Maps 1

Chapter 13.2: Topographic Maps 1 A map is a model or representation of objects and terrain in the actual environment. There are numerous types of maps. Some of the types of maps include mental, planimetric, topographic, and even treasure maps. The concept of mapping was introduced in the section using natural features. Maps are created for numerous purposes. A treasure map is used to find the buried treasure. Topographic maps were originally used for military purposes. Today, they have been used for planning and recreational purposes. Although other types of maps are mentioned, the primary focus of this section is on topographic maps. Types of Maps Mental Maps – The mind makes mental maps all the time. You drive to the grocery store. You turn right onto the boulevard. You identify a street sign, building or other landmark and know where this is where you turn. You have made a mental map. This was discussed under using natural features. Planimetric Maps – A planimetric map is a two dimensional representation of objects in the environment. Generally, planimetric maps do not include topographic representation. Road maps, Rand McNally ® and GoogleMaps ® (not GoogleEarth) are examples of planimetric maps. Topographic Maps – Topographic maps show elevation or three-dimensional topography two dimensionally. Topographic maps use contour lines to show elevation. A chart refers to a nautical chart. Nautical charts are topographic maps in reverse. Rather than giving elevation, they provide equal levels of water depth. Topographic Maps Topographic maps show elevation or three-dimensional topography two dimensionally. Topographic maps use contour lines to show elevation. -

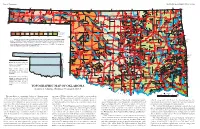

TOPOGRAPHIC MAP of OKLAHOMA Kenneth S

Page 2, Topographic EDUCATIONAL PUBLICATION 9: 2008 Contour lines (in feet) are generalized from U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps (scale, 1:250,000). Principal meridians and base lines (dotted black lines) are references for subdividing land into sections, townships, and ranges. Spot elevations ( feet) are given for select geographic features from detailed topographic maps (scale, 1:24,000). The geographic center of Oklahoma is just north of Oklahoma City. Dimensions of Oklahoma Distances: shown in miles (and kilometers), calculated by Myers and Vosburg (1964). Area: 69,919 square miles (181,090 square kilometers), or 44,748,000 acres (18,109,000 hectares). Geographic Center of Okla- homa: the point, just north of Oklahoma City, where you could “balance” the State, if it were completely flat (see topographic map). TOPOGRAPHIC MAP OF OKLAHOMA Kenneth S. Johnson, Oklahoma Geological Survey This map shows the topographic features of Oklahoma using tain ranges (Wichita, Arbuckle, and Ouachita) occur in southern contour lines, or lines of equal elevation above sea level. The high- Oklahoma, although mountainous and hilly areas exist in other parts est elevation (4,973 ft) in Oklahoma is on Black Mesa, in the north- of the State. The map on page 8 shows the geomorphic provinces The Ouachita (pronounced “Wa-she-tah”) Mountains in south- 2,568 ft, rising about 2,000 ft above the surrounding plains. The west corner of the Panhandle; the lowest elevation (287 ft) is where of Oklahoma and describes many of the geographic features men- eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas is a curved belt of forested largest mountainous area in the region is the Sans Bois Mountains, Little River flows into Arkansas, near the southeast corner of the tioned below. -

Parameters Derived from And/Or Used with Digital Elevation Models (Dems) for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping and Landslide Risk Assessment: a Review

International Journal of Geo-Information Review Parameters Derived from and/or Used with Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping and Landslide Risk Assessment: A Review Nayyer Saleem * , Md. Enamul Huq , Nana Yaw Danquah Twumasi, Akib Javed and Asif Sajjad State Key Laboratory of Information Engineering in Surveying, Mapping and Remote Sensing, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430079, China; [email protected] (M.E.H.); [email protected] (N.Y.D.T.); [email protected] (A.J.); [email protected] (A.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-131-6411-7422 Received: 15 September 2019; Accepted: 27 November 2019; Published: 29 November 2019 Abstract: Digital elevation models (DEMs) are considered an imperative tool for many 3D visualization applications; however, for applications related to topography, they are exploited mostly as a basic source of information. In the study of landslide susceptibility mapping, parameters or landslide conditioning factors are deduced from the information related to DEMs, especially elevation. In this paper conditioning factors related with topography are analyzed and the impact of resolution and accuracy of DEMs on these factors is discussed. Previously conducted research on landslide susceptibility mapping using these factors or parameters through exploiting different methods or models in the last two decades is reviewed, and modern trends in this field are presented in a tabulated form. Two factors or parameters are proposed for inclusion in landslide inventory list as a conditioning factor and a risk assessment parameter for future studies. Keywords: digital elevation models (DEMs); landslide hazards; landslide susceptibility mapping; landslide conditioning factors; landslide risk assessment 1. -

What Is Geovisualization? to the Growing Field of Geovisualization

This issue of GeoMatters is devoted What is Geovisualization? to the growing field of geovisualization. Brian McGregor uses geovisualiztion to by Joni Storie produce animated maps showing settle- ment patterns of Hutterite colonies. Dr. Marc Vachon’s students use it to produce From a cartography perspective, dynamic presentation options to com- videos about urban visualization (City geovisualization represents a change in municate knowledge. For example, at- Hall and Assiniboine Park), while Dr. how knowledge is formed and repre- lases require extra planning compared Chris Storie shows geovisualiztion for sented. Traditional cartography is usu- to individual maps, structurally they retail mapping in Winnipeg. Also in this issue Honours students describe their ally seen a visualization (a.k.a. map) could include hundreds of maps, and thesis projects for the upcoming collo- that is presented after the conclusion all the maps relate to each other. Dr. quium next March, Adrienne Ducharme is reached to emphasize or compliment Danny Blair and Dr. Ian Mauro, in the tells us about her graduate research at the research conclusions. Geovisual- Department of Geography, provide an ELA, we have a report about Cultivate ization changes this format by incor- excellent example of this integration UWinnipeg and our alumni profile fea- porating spatial data into the analysis with the Prairie Climate Atlas (http:// tures Michelle Méthot (Smith). (O’Sullivan and Unwin, 2010). Spatial www.climateatlas.ca/). The combina- Please feel free to pass this newsletter data, statistics and analysis are used to tion of maps with multimedia provides to anyone with an interest in geography. answer questions which contribute to for better understanding as well as en- Individuals can also see GeoMatters at the Geography website, or keep up with the conclusion that is reached within riched and informative experiences of us on Facebook (Department of Geog- the research. -

Comparative Analysis of Digital Elevation Models: a Case Study Around Madduleru River

Indian Journal of Geo Marine Sciences Vol. 46 (07), July 2017, pp. 1339-1351 Comparative analysis of digital elevation models: A case study around Madduleru River Subbu Lakshmi. E1 & Kiran Yarrakula2* Centre for Disaster Mitigation and Management, VIT University, Vellore, Pin 632014, India *[E-mail: [email protected]] Received 14 July 2016 ; revised 28 November 2016 High resolution DEM is generated from Cartosat-1 stereo data. The performance of different DEMs is evaluated based on error statistics. To identify the hill profiles, the TIN plots have generated and compared for SRTM, Cartosat -1, and SOI toposheet. The study divulges that, elevation values of Cartosat-1 DEM are better in flat terrain and SRTM images in hilly region produced better, when compared each other. [Keywords: Cartosat-1 DEM, SRTM-DEM, Google earth, Survey of India Toposheet, Accuracy Assessment, Digital elevation model] Introduction corresponding image points are identified in the Cartosat-1 DEM with 2.5m spatial particular stereo images In general, the accuracy resolution and vertical resolution 7.5m is intended of Cartosat-1 DEM seems to be fine in the flat to be used for generating DEM. The ground terrain which is helpful to interpret the land control points and geometric model are the features13. Past few years many scientists and essential components required for generating researchers have done a series of local and global DEM from stereo data1. DEM in variety of assessments of these elevation products. Many application such as land use land cover to analyze new technologies are giving opportunities for the spatio-temporal change on the river2&3, generating digital elevation models in remote cadastral mapping, to assess the vertical sensing to determine Earth surface elevation at characteristics of topographical variability of increasing resolution for larger areas14. -

AN ASSESSMENT of DIGITAL ELEVATION MODELS (Dems) from DIFFERENT SPATIAL DATA SOURCES

AN ASSESSMENT OF DIGITAL ELEVATION MODELS (DEMs) FROM DIFFERENT SPATIAL DATA SOURCES Olalekan Adekunle ISIOYE, Nigeria And JOBI N Paul, Nigeria Key words : Digital Elevation Model (DEM), Google Earth image, SRTM, spot height SUMMARY Digital Elevation Model (DEM) represents a very important geospatial data type in the analysis and modelling of different hydrological and ecological phenomenon which are required in preserving our immediate environment. DEMs are typically used to represent terrain relief. DEMs are particularly relevant for many applications such as lake and water volumes estimation, soil erosion volumes calculations, flood estimate, quantification of earth materials to be moved for channels, roads, dams, embankment etc. In this study, three different sources of spatial data in the generation of DEMs (Shuttle Radar Topography Mission SRTM 30, Digitized Topographical map and Google Earth Pro.) were compared with field measured data from Total Station Instrument, the field data were used to generate a Digital Elevation Models DEMs from 495 radial points over the test site. The accuracy of generated DEMs were assessed statistically by comparing (1) estimates of some topographic attributes(slope and aspect), (2)overall spot height estimation performance and, (3) independence of spot estimation errors and the magnitude of field measured height. From the results obtained it was concluded that the DEMs from the satellite imagery (SRTM 30) does not perform well in collecting data for topographic works. The digitized topographic map gives a good result but the variation from the reference in this study may be as a result of human activities and erosion that has occurred from when the topographic map was produced and also the quality of the topographic map. -

Geomorphometry of Cerro Sillajhuay (Andes, Chile/Bolivia): Comparison of Digital Elevation Models (Dems) from ASTER Remote Sensing Data and Contour Maps

Geomorphometry of Cerro Sillajhuay (Andes, Chile/Bolivia): Comparison of Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) from ASTER Remote Sensing Data and Contour Maps Ulrich Kamp Department of Geography and Environmental Science Program, DePaul University 990 W Fullerton Ave, Chicago, IL 60614-2458, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] Tobias Bolch Department of Geography, Humboldt University Berlin Rudower Chausse 16, Unter den Linden 6, 10099 Berlin, Germany E-mail: [email protected] Jeffrey Olsenholler Department of Geography and Geology, University of Nebraska - Omaha 6001 Dodge Street, Omaha, NE 68182-0199, U.S.A. [email protected] Abstract Digital elevation models (DEMs) are increasingly used for visual and mathematical analysis of topography, landscapes and landforms, as well as modeling of surface processes. To accomplish this, the DEM must represent the terrain as accurately as possible, since the accuracy of the DEM determines the reliability of the geomorphometric analysis. For Cerro Sillajhuay in the Andes of Chile/Bolivia two DEMs are compared: one derived from contour maps, the other from a satellite stereo-pair from the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER). As both DEM procedures produce estimates of elevation, quantative analysis of each DEM was limited. The original ASTER DEM has a horizontal resolution of 30 m and was generated using tie points (TPs) and ground control points (GCPs). It was then resampled to 15 m resolution, the resolution of the VNIR bands. Five parameters were calculated for geomorphometric interpretation: elevation, slope angle, slope aspect, vertical curvature, and tangential curvature. Other calculations include flow lines and solar radiation.