Direct Measurement of Stellar Angular Diameters by the VERITAS Cherenkov Telescopes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses First visibility of the lunar crescent and other problems in historical astronomy. Fatoohi, Louay J. How to cite: Fatoohi, Louay J. (1998) First visibility of the lunar crescent and other problems in historical astronomy., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/996/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk me91 In the name of Allah, the Gracious, the Merciful >° 9 43'' 0' eji e' e e> igo4 U61 J CO J: lic 6..ý v Lo ý , ý.,, "ý J ýs ýºý. ur ý,r11 Lýi is' ý9r ZU LZJE rju No disaster can befall on the earth or in your souls but it is in a book before We bring it into being; that is easy for Allah. In order that you may not grieve for what has escaped you, nor be exultant at what He has given you; and Allah does not love any prideful boaster. -

Young Super-Neptune Offers Clues to the Origin of Close-In Exoplanet 21 June 2016, by Rebecca Johnson

Young super-Neptune offers clues to the origin of close-in exoplanet 21 June 2016, by Rebecca Johnson planets in the same planetary system, or with more distant stars. These scenarios can be tested observationally by searching for young planets and studying their orbits. If the close-in population formed in place or migrated in through interactions with the natal disk, they reach their final orbital distances early on and will be found close in at young ages. In comparison, migrating a planet inward through interactions with other planets or more distant stars is effective on much longer timescales. If the latter processes dominate, planets will not be found close to their K2-33 b, shown in this illustration, is one of the youngest stars when they are young. exoplanets detected to date. It makes a complete orbit around its star in about five days. These two characteristics combined provide exciting new directions for planet-formation theories. K2-33b could have formed on a farther out orbit and quickly migrated inward. Alternatively, it could have formed in situ, or in place. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech A team of astronomers has confirmed the existence of a young planet, only 11 million years old, that orbits very close to its star (at 0.05 AU), with an orbital period of 5.4 days. Approximately 5 times the size of the Earth, the new planet is a "super-Neptune" and the youngest such planet This image shows the K2-33 system, and its planet known. The discovery lends unique insights into K2-33b, compared to our own solar system. -

Educator's Guide: Orion

Legends of the Night Sky Orion Educator’s Guide Grades K - 8 Written By: Dr. Phil Wymer, Ph.D. & Art Klinger Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………....3 Constellations; General Overview……………………………………..4 Orion…………………………………………………………………………..22 Scorpius……………………………………………………………………….36 Canis Major…………………………………………………………………..45 Canis Minor…………………………………………………………………..52 Lesson Plans………………………………………………………………….56 Coloring Book…………………………………………………………………….….57 Hand Angles……………………………………………………………………….…64 Constellation Research..…………………………………………………….……71 When and Where to View Orion…………………………………….……..…77 Angles For Locating Orion..…………………………………………...……….78 Overhead Projector Punch Out of Orion……………………………………82 Where on Earth is: Thrace, Lemnos, and Crete?.............................83 Appendix………………………………………………………………………86 Copyright©2003, Audio Visual Imagineering, Inc. 2 Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Introduction It is our belief that “Legends of the Night sky: Orion” is the best multi-grade (K – 8), multi-disciplinary education package on the market today. It consists of a humorous 24-minute show and educator’s package. The Orion Educator’s Guide is designed for Planetarians, Teachers, and parents. The information is researched, organized, and laid out so that the educator need not spend hours coming up with lesson plans or labs. This has already been accomplished by certified educators. The guide is written to alleviate the fear of space and the night sky (that many elementary and middle school teachers have) when it comes to that section of the science lesson plan. It is an excellent tool that allows the parents to be a part of the learning experience. The guide is devised in such a way that there are plenty of visuals to assist the educator and student in finding the Winter constellations. -

September 2020 BRAS Newsletter

A Neowise Comet 2020, photo by Ralf Rohner of Skypointer Photography Monthly Meeting September 14th at 7:00 PM, via Jitsi (Monthly meetings are on 2nd Mondays at Highland Road Park Observatory, temporarily during quarantine at meet.jit.si/BRASMeets). GUEST SPEAKER: NASA Michoud Assembly Facility Director, Robert Champion What's In This Issue? President’s Message Secretary's Summary Business Meeting Minutes Outreach Report Asteroid and Comet News Light Pollution Committee Report Globe at Night Member’s Corner –My Quest For A Dark Place, by Chris Carlton Astro-Photos by BRAS Members Messages from the HRPO REMOTE DISCUSSION Solar Viewing Plus Night Mercurian Elongation Spooky Sensation Great Martian Opposition Observing Notes: Aquila – The Eagle Like this newsletter? See PAST ISSUES online back to 2009 Visit us on Facebook – Baton Rouge Astronomical Society Baton Rouge Astronomical Society Newsletter, Night Visions Page 2 of 27 September 2020 President’s Message Welcome to September. You may have noticed that this newsletter is showing up a little bit later than usual, and it’s for good reason: release of the newsletter will now happen after the monthly business meeting so that we can have a chance to keep everybody up to date on the latest information. Sometimes, this will mean the newsletter shows up a couple of days late. But, the upshot is that you’ll now be able to see what we discussed at the recent business meeting and have time to digest it before our general meeting in case you want to give some feedback. Now that we’re on the new format, business meetings (and the oft neglected Light Pollution Committee Meeting), are going to start being open to all members of the club again by simply joining up in the respective chat rooms the Wednesday before the first Monday of the month—which I encourage people to do, especially if you have some ideas you want to see the club put into action. -

Instrumental Methods for Professional and Amateur

Instrumental Methods for Professional and Amateur Collaborations in Planetary Astronomy Olivier Mousis, Ricardo Hueso, Jean-Philippe Beaulieu, Sylvain Bouley, Benoît Carry, Francois Colas, Alain Klotz, Christophe Pellier, Jean-Marc Petit, Philippe Rousselot, et al. To cite this version: Olivier Mousis, Ricardo Hueso, Jean-Philippe Beaulieu, Sylvain Bouley, Benoît Carry, et al.. Instru- mental Methods for Professional and Amateur Collaborations in Planetary Astronomy. Experimental Astronomy, Springer Link, 2014, 38 (1-2), pp.91-191. 10.1007/s10686-014-9379-0. hal-00833466 HAL Id: hal-00833466 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00833466 Submitted on 3 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Instrumental Methods for Professional and Amateur Collaborations in Planetary Astronomy O. Mousis, R. Hueso, J.-P. Beaulieu, S. Bouley, B. Carry, F. Colas, A. Klotz, C. Pellier, J.-M. Petit, P. Rousselot, M. Ali-Dib, W. Beisker, M. Birlan, C. Buil, A. Delsanti, E. Frappa, H. B. Hammel, A.-C. Levasseur-Regourd, G. S. Orton, A. Sanchez-Lavega,´ A. Santerne, P. Tanga, J. Vaubaillon, B. Zanda, D. Baratoux, T. Bohm,¨ V. Boudon, A. Bouquet, L. Buzzi, J.-L. Dauvergne, A. -

Serpens – the Serpent

A JPL Image of surface of Mars, and JPL Ingenuity Helicioptor illustration, in flight Monthly Meeting May 10th at 7:00 PM at HRPO, and via Jitsi (Monthly meetings are on 2nd Mondays at Highland Road Park Observatory, will also broadcast via. (meet.jit.si/BRASMeet). PRESENTATION: Dr. Alan Hale, professional astronomer and co-discoverer of Comet Hale-Bopp, among other endeavors. What's In This Issue? President’s Message Member Meeting Minutes Business Meeting Minutes Outreach Report Light Pollution Committee Report Globe at Night SubReddit and Discord Messages from the HRPO REMOTE DISCUSSION Solar Viewing International Astronomy Day American Radio Relay League Field Day Observing Notes: Serpens - The Serpent & Mythology Like this newsletter? See PAST ISSUES online back to 2009 Visit us on Facebook – Baton Rouge Astronomical Society BRAS YouTube Channel Baton Rouge Astronomical Society Newsletter, Night Visions Page 2 of 20 May 2021 President’s Message Ahhh, welcome to May, the last pleasant month in Louisiana before the start of the hurricane season and the brutal summer months that follow. April flew by pretty quickly, and with the world slowly thawing from the long winter, why shouldn’t it? To celebrate, we decided we’re going to try to start holding our monthly meetings at Highland Road Park Observatory again, only with the added twist of incorporating an on-line component for those who for whatever reason don’t feel like making it out. To that end, we’ll have both our usual live broadcast on the BRAS YouTube channel and the Brasmeet page on Jitsi—which is where our out of town guests and, at least this month, our guest speaker can join us. -

1455189355674.Pdf

THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN Cover by: Peter Bradley LEGAL PAGE: Every effort has been made not to make use of proprietary or copyrighted materi- al. Any mention of actual commercial products in this book does not constitute an endorsement. www.trolllord.com www.chenaultandgraypublishing.com Email:[email protected] Printed in U.S.A © 2013 Chenault & Gray Publishing, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Storyteller’s Thesaurus Trademark of Cheanult & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Chenault & Gray Publishing, Troll Lord Games logos are Trademark of Chenault & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS 1 FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR 1 JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN 1 INTRODUCTION 8 WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT 8 THE STORYTeller’s RESPONSIBILITY: RESEARCH 9 WHAT THIS BOOK DOES NOT CONTAIN 9 A WHISPER OF ENCOURAGEMENT 10 CHAPTER 1: CHARACTER BUILDING 11 GENDER 11 AGE 11 PHYSICAL AttRIBUTES 11 SIZE AND BODY TYPE 11 FACIAL FEATURES 12 HAIR 13 SPECIES 13 PERSONALITY 14 PHOBIAS 15 OCCUPATIONS 17 ADVENTURERS 17 CIVILIANS 18 ORGANIZATIONS 21 CHAPTER 2: CLOTHING 22 STYLES OF DRESS 22 CLOTHING PIECES 22 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 24 CHAPTER 3: ARCHITECTURE AND PROPERTY 25 ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AND ELEMENTS 25 BUILDING MATERIALS 26 PROPERTY TYPES 26 SPECIALTY ANATOMY 29 CHAPTER 4: FURNISHINGS 30 CHAPTER 5: EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 ADVENTurer’S GEAR 31 GENERAL EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 2 THE STORYTeller’s Thesaurus KITCHEN EQUIPMENT 35 LINENS 36 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS -

Differential Photometry of Delta Scorpii During 2011 Periastron 3

IL NUOVO CIMENTO Vol. ?, N. ? ? Differential photometry of delta Scorpii during 2011 periastron C. Sigismondi(1)(2)(3)(4)(5) (1) Sapienza University of Rome, P.le Aldo Moro 5 00185, Roma (Italy) (2) ICRA, International Center for Relativistic Astrophysics, P.le Aldo Moro 5 00185, Roma (Italy) (3) Universit´ede Nice-Sophia Antipolis (France) (4) Istituto Ricerche Solari di Locarno (Switzerland) (5) GPA, Observatorio Nacional, Rio de Janeiro (Brasil) Summary. — Hundred observations of Delta Scorpii over 200 days, from April 2 to October 16, 2011, have been made for AAVSO visually and digitally from Rio de Janeiro, Rome and Paris. The three most luminous pixels either of the target star and the two reference stars are used to evaluate the magnitude through differential photometry. The main sources of errors are outlined. The system of Delta Scorpii, a spectroscopic double star, has experienced a close periastron in July 2011 within the outer atmospheres of the two giant components. The whole luminosity of Delta Scorpii system increased from about Mv=1.8 to 1.65 peaking around 5 to 15 July 2011, but there are significant rapid fluctuations of 0.2 - 0.3 magnitudes occurring in 20 days that seem to be real, rather than a consequence of systematic errors due to the changes of reference stars and observing conditions. This method is promising for being applied to other bright variable stars like Betelgeuse and Antares. After August the magnitude remained constant at Mv=1.8 until the last observation on October 16 made in twilight from Rome. PACS 95.75.Tv – Digital imaging astronomy. -

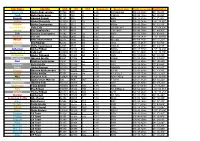

Star Name Identity SAO HD FK5 Magnitude Spectral Class Right Ascension Declination Alpheratz Alpha Andromedae 73765 358 1 2,06 B

Star Name Identity SAO HD FK5 Magnitude Spectral class Right ascension Declination Alpheratz Alpha Andromedae 73765 358 1 2,06 B8IVpMnHg 00h 08,388m 29° 05,433' Caph Beta Cassiopeiae 21133 432 2 2,27 F2III-IV 00h 09,178m 59° 08,983' Algenib Gamma Pegasi 91781 886 7 2,83 B2IV 00h 13,237m 15° 11,017' Ankaa Alpha Phoenicis 215093 2261 12 2,39 K0III 00h 26,283m - 42° 18,367' Schedar Alpha Cassiopeiae 21609 3712 21 2,23 K0IIIa 00h 40,508m 56° 32,233' Deneb Kaitos Beta Ceti 147420 4128 22 2,04 G9.5IIICH-1 00h 43,590m - 17° 59,200' Achird Eta Cassiopeiae 21732 4614 3,44 F9V+dM0 00h 49,100m 57° 48,950' Tsih Gamma Cassiopeiae 11482 5394 32 2,47 B0IVe 00h 56,708m 60° 43,000' Haratan Eta ceti 147632 6805 40 3,45 K1 01h 08,583m - 10° 10,933' Mirach Beta Andromedae 54471 6860 42 2,06 M0+IIIa 01h 09,732m 35° 37,233' Alpherg Eta Piscium 92484 9270 50 3,62 G8III 01h 13,483m 15° 20,750' Rukbah Delta Cassiopeiae 22268 8538 48 2,66 A5III-IV 01h 25,817m 60° 14,117' Achernar Alpha Eridani 232481 10144 54 0,46 B3Vpe 01h 37,715m - 57° 14,200' Baten Kaitos Zeta Ceti 148059 11353 62 3,74 K0IIIBa0.1 01h 51,460m - 10° 20,100' Mothallah Alpha Trianguli 74996 11443 64 3,41 F6IV 01h 53,082m 29° 34,733' Mesarthim Gamma Arietis 92681 11502 3,88 A1pSi 01h 53,530m 19° 17,617' Navi Epsilon Cassiopeiae 12031 11415 63 3,38 B3III 01h 54,395m 63° 40,200' Sheratan Beta Arietis 75012 11636 66 2,64 A5V 01h 54,640m 20° 48,483' Risha Alpha Piscium 110291 12447 3,79 A0pSiSr 02h 02,047m 02° 45,817' Almach Gamma Andromedae 37734 12533 73 2,26 K3-IIb 02h 03,900m 42° 19,783' Hamal Alpha -

Scorpius for the Big Dipper's Celebrated Duo

DOUBLE STl•i.~S OF THE MJNTH by GZenn F. ChapZe, Jr. Southern sky objects tend to be ig- nored·b~observers in northerly latitu- des. Except for an occasional swipe at a Messier object, we usually bypass celestial objects that flirt with the treetops. When the results of last .year's "Top Ten Doubles" survey were tabulated, I was surprised to see the poor showing of BETA SCORPII (16h 02.5m; ,.: 190 40'), one of my favorites. The upper~ost of a graceful arc of bright stars that includes Scorpion members lIIU I1h':103 0 Delta and Pi, Beta (also called Akrab) ~.. o SETA is as attractive as it is easy to find. .H~:'~ BOME.(,A' Its resemblance to Mizar is more than o M'E,(,A 1 mere coincedence. The magnitudes (2.6 and 4.9) and separation (13.7") 6f its es member stars closely match the figures SCORPiUS for the Big Dipper's celebrated duo. Once you've captured Akrab in your tele- scope,look closely at the fainter com- ponent. ~t seems to sparkle with a dis- tinct blue or blue-green color that con- trasts nicely with the strong white light of the primary. Akrab isa quin- tuple star; the rest of the family is beyond the reach of small to medium-sized There is yet another multiple star in the telescopes. area! This is NU SCORPII (16h 09.1 m; -190 21'), a quadruple star situated a scant Almost 8~0 due· north of Akrab, at 16h degree-and-a-half east of Akrab. -

Brightest Stars : Discovering the Universe Through the Sky's Most Brilliant Stars / Fred Schaaf

ffirs.qxd 3/5/08 6:26 AM Page i THE BRIGHTEST STARS DISCOVERING THE UNIVERSE THROUGH THE SKY’S MOST BRILLIANT STARS Fred Schaaf John Wiley & Sons, Inc. flast.qxd 3/5/08 6:28 AM Page vi ffirs.qxd 3/5/08 6:26 AM Page i THE BRIGHTEST STARS DISCOVERING THE UNIVERSE THROUGH THE SKY’S MOST BRILLIANT STARS Fred Schaaf John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.qxd 3/5/08 6:26 AM Page ii This book is dedicated to my wife, Mamie, who has been the Sirius of my life. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2008 by Fred Schaaf. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada Illustration credits appear on page 272. Design and composition by Navta Associates, Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copy- right.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. -

Contributions Bosscha Observatory

BANDUNG INSTITUTE OF s'4XI-INOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE CONTRIBUTIONS from the BOSSCHA OBSERVATORY No. 45 PHOTOGRAPHIC OBSERVATIONS OF THE OCCULTATION - OF BETA SCORPII BY JUPITER by Stephen M. Larson 1 NATIONAL TECHNICAL l INFORMATION SERVICE I US Department of Commerce . .Spring.field, VA. 22151 (NASA-CR-12 9990) PHOTOGRAPHIC 'OBSERVATIONS OF THE OCCULTATION OF BETA JSCORPII BY JUPITER S.M. Larson i(Observatorium Bosscha) 1972 12 p C ______ ___ CSCL 03A G3/30 BN73-14832 ,I 832 .4 Unclas % Published with financial support 50 507 of the I.T.B. - Pelita Funds 1972 P PHOTOGRAPHIC OBSERVATIONS OF THE OCCULTATION * I'.C $p~;OF BETA SCORPII BY JUPITER 'fl. Cla . -,:: b * // ....- l: *~ v Stephen M. Larson Lunar and. Planetary Laboratory *: >~.nimiv, , -. University of Arizona - ..i " ,,, tucson Arizona ear 'odi sloe19-, 857?21 " ~iu2aoqxe edt d','d : nstc; : :. evinirIneseiqei ized : evie oi b.. 0ib"os V rh-q' . ;; n-, -- ~tormrloim ' -ABSTRACT The occultation of the multiple star Beta Scorpii by Jupiter wasobservedvisually andphotographically fr6m the Bosscha Ob- servatory in Lembang (Java) , Indonesia, on May 13 , 1971 .The photographs recorded the dimming of the stars as the light was differentially refracted by the Jovian atmosphere, and gave support to a scale height greater than 8 km. Measurement of the position of the brightest component of Beta Scorpii during in- ~gess lshosysrefractDio of -.-approximately 1'.'4 before becoming >nv,lsteppr~act:- i *o-n unobsimbev,pe,pm(,e ;.;,,:.o:.~¢~ f)l3 ~, oi.% -;;.; :.'; *; -:": - q,1 OIg i 7:021i2w 1r· : " 'r " ' ,;'f' '.- ,INTRODUCTION .... qt2 .",: : . z'. ;- . .:,,~L9serv.ving.rnswas rniade ,at.the, Bosscha Observatory in Lemibang,(Jaya), Indonesia during1the:month of May 1971 (Larson 1971- ),,in,, Prpparation.