NARA Disclosure 8/00

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

Final Report of the Nazi War Crimes & Japanese

Nazi War Crimes & Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group Final Report to the United States Congress April 2007 Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group Final Report to the United States Congress Published April 2007 1-880875-30-6 “In a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people not to be on the side of the executioners.” — Albert Camus iv IWG Membership Allen Weinstein, Archivist of the United States, Chair Thomas H. Baer, Public Member Richard Ben-Veniste, Public Member Elizabeth Holtzman, Public Member Historian of the Department of State The Secretary of Defense The Attorney General Director of the Central Intelligence Agency Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation National Security Council Director of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum Nationa5lrchives ~~ \T,I "I, I I I"" April 2007 I am pleased to present to Congress. Ihe AdnllniSlr:lllon, and the Amcncan [JeOplc Ihe Final Report of the Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Rcrords Interagency Working Group (IWG). The lWG has no\\ successfully completed the work mandated by the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act (P.L. 105-246) and the Japanese Imperial Government DisdoSUTC Act (PL 106·567). Over 8.5 million pages of records relaH:d 10 Japanese and Nazi "'ar crimes have been identifIed among Federal Go\emmelll records and opened to the pubhc. including certam types of records nevcr before released. such as CIA operational Iiles. The groundbrcaking release of Lhcse ft:cords In no way threatens lhe Malio,,'s sccurily. -

The Psychology and Politics of Ludwig Carl Moyzisch, Author of Operation Cicero

International Journal of Arts & Sciences, CD-ROM. ISSN: 1944-6934 :: 09(04):227–232 (2017) THE PSYCHOLOGY AND POLITICS OF LUDWIG CARL MOYZISCH, AUTHOR OF OPERATION CICERO William W. Bostock University of Tasmania, Australia This article explores the intimate relationship between psychology and personal politics, as shown in the life of Ludwig Carl Moyzisch, the handler of Cicero, who was arguably the most successful spy of World War II. An analysis of Moyzisch’s book ‘Operation Cicero’ and other sources reveal Moyzisch to be a man possessing the qualities of astuteness, imagination and empathy, but also being of doubtful moral compass. There is also evidence of uncertainty over personal identity, a characteristic which can explain his successful handling of Elyesa Bazna, also known as Cicero, himself a man of confused identity. Keywords: Moyzisch, Cicero, Bazna, Von Papen, Knatchbull-Hugessen, Schellenberg. From October 1943 until March 1944, the British Embassy in Ankara was the site of a leakage of information in the form of photographs of Most Secret documents that were potentially disastrous for the Allied cause in World War Two, had the Nazi leadership acted upon them. They included the texts of the Allied conferences at Cairo and Teheran, attempts to get Turkey into World War II on the Allied side, and references to Operation Overlord, the forthcoming D Day Landing. The source of this leakage was Elyesa Diello Bazna, an ethnic Albanian of Turkish citizenship and Muslim religion, who was valet to Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen, British Ambassador to Turkey. While Sir Hugh was sleeping or taking his twice daily bath, his valet Bazna was able to photograph a large number of important and top secret documents, which he then offered for sale to the German Embassy for an outrageous price. -

Istanbul Intrigues

Istanbul Intrigues by Barry Rubin, 1950-2014 Published: 1989 J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents Author‘s Note Preface Poems & Chapter 1 … Diplomacy by Murder. Chapter 2 … Sailing to Istanbul. Chapter 3 … Intimations of Catastrophe. Chapter 4 … At the Court of Spies. Chapter 5 … The Last Springtime. Chapter 6 … The Front Line Comes to Istanbul. Chapter 7 … The Story Pursues the Journalists. Chapter 8 … The Americans Arrive: 1942-1943. Chapter 9 … American Ignorance and Intelligence. Chapter 10 … The Archaeologist’s Navy: The OSS in the Aegean, 1943-1944. Chapter 11 … Dogwood’s Bark: OSS Successes in Istanbul. Chapter 12 … Dogwood’s Bite: The Fall of OSS-Istanbul. Chapter 13 … Rescue from Hell. Chapter 14 … Germany’s Defective Intelligence. Chapter 15 … The Valet Did It. Chapter 16 … World War to Cold War. Epilogue Selective List of Code Names for OSS-Turkey Intelligence Organizations Interviews Acknowledgements J J J J J I I I I I Author‘s Note This is the story of Istanbul—but also of Turkey, the Balkans, and the eastern Mediterranean—during World War II, based on extensive interviews and the use of archives, especially those of the OSS, which I was the first to see for this region. The book is written as a cross between a scholarly work and a real-life thriller. The status of Turkey as a neutral country made it a center of espionage, a sort of actual equivalent of the film Casablanca . Aspects of the story include the Allied-Axis struggle to get Turkey on their side; the spy rings set up in the Middle East and the Balkans; the attempts of Jews to escape through Turkey; the Allies’ covert war in Greece, Yugoslavia, Hungary, and other countries; and the first accurate account of how the Germans recruited the British ambassador’s valet as a spy, who could have been their most successful agent of the war if only they had listened to his warnings. -

Secrets in Switzerland : Allen W. Dulles' Impact As OSS Station Chief in Bern on Developments of World War II & U.S

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2009 Secrets in Switzerland : Allen W. Dulles' impact as OSS station chief in Bern on developments of World War II & U.S. dominance in post-war Europe Jennifer A. Hoover College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hoover, Jennifer A., "Secrets in Switzerland : Allen W. Dulles' impact as OSS station chief in Bern on developments of World War II & U.S. dominance in post-war Europe" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 240. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/240 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SECRETS IN SWITZERLAND: ALLEN W. DULLES’ IMPACT AS OSS STATION CHIEF IN BERN ON DEVELOPMENTS OF WORLD WAR II & U.S. DOMINANCE IN POSTWAR EUROPE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in History from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, by Jennifer A. Hoover Accepted for ___________________________ _________________________________ Professor Hiroshi Kitamura Director _________________________________ Professor David McCarthy _________________________________ Professor William Rennagel Williamsburg, VA May 2008 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank many people for their help, guidance, and support throughout my thesis writing process. Dr. Hiroshi Kitamura helped me work through all the phases of this research project, and I am grateful for his advisement and encouragement. -

Guide to Western Intelligence During the Holocaust

Series IV Volume 9 Eavesdropping on Hell: Historical Guide to Western Communications Intelligence and the Holocaust, 1939-1945 UNITED STATES CRYPTOLOGIC HISTORY Eavesdropping on Hell: Historical Guide to Western Communications Intelligence and the Holocaust, 1939-1945 Robert J. Hanyok CENTER FOR CRYPTOLOGIC HISTORY NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY 2004 Table of Contents Page Table of Contents . .iii Preface and Acknowledgments . .1 A Note on Terminology . 5 Acknowledgments . 7 Chapter 1: Background . .11 The Context of European and Nazi Anti-Semitism . .11 Previous Histories and Articles . .14 Chapter 2: Overview of the Western Communications Intelligence System during World War II . 21 Step 1: Setting the Requirements, Priorities, and Division of Effort . .24 Step 2: Intercepting the Messages . .29 Step 3: Processing the Intercept . .36 Step 4: Disseminating the COMINT . .43 From Intercept to Decryption the Processing of a German Police Message . .51 Chapter 3: Sources of Cryptologic Records Relating to the Holocaust . .61 The National Archives and Records Administration . .61 The Public Record Office . .67 Miscellaneous Collections . .71 Chapter 4: Selected Topics from the Holocaust . .75 A. The General Course of the Holocaust and Allied COMINT . .76 B. Jewish Refugees, the Holocaust, and the Growing Strife in Palestine . .86 C. The Vichy Regime and the Jews . .89 D. The Destruction of Hungarys Jews, 1944 . .99 E. Japan and the Jews in the Far East . .97 F. Nazi Gold: National and Personal Assests Looted by Nazis and Placed in Swiss Banks, 1943 - 1945 . .104 Chapter 5: Some Observations about Western Communications Intelligence and the Holocaust . .. .121 What was Known from COMINT . .122 When the COMINT Agencies Knew . -

213471631.Pdf

PREFACE This is a book about Istanbul and about those who conducted political and espionage missions there during the Second World War. It is a work of nonfiction based on extensive archival research and interviews. Each event and every conversation is reconstructed as accurately as possible. Whenever I interviewed those involved, four decades after the events herein described, there always came a moment when these Americans, Austrians, Czechs, Germans, Hungarians, Israelis, Russians, and Turks would almost visibly reach back in time. Their eyes would light up in recalling those remarkable days that had forever marked their Jives. To some, these were moments of great achievement and romance; to others, searing tragedy. For all of them, it was an era of great perils and passionate idealism when they hoped their actions would shape a new world. One of Istanbul's most intriguing wartime characters was Wilhelm Hamburger. A highly successful German intelligence officer who later defected to the British, Hamburger then disappeared from history until I found--on my last day of research in the OSS archives--one of his letters that the ass had intercepted in 1945. In a postscript, Hamburger mentioned the new name he was taking. After checking a Vienna telephone book, I had his address within an hour. It was particularly meaningful for me to visit Vienna a century to the day after my great- grandfather left there for America. I walked to Hamburger's apartment down streets named for the city's great composers. Wiry and charming, as described in Allied intelligence reports forty years earlier, he spoke with me for six hours. -

From Axis Surprises to Allied Victories from AFIO's the INTELLIGENCER

Association of Former Intelligence Officers From AFIO's The Intelligencer 7700 Leesburg Pike, Suite 324 Journal of U.S. Intelligence Studies Falls Church, Virginia 22043 Web: www.afio.com, E-mail: [email protected] Volume 22 • Number 3 • $15 single copy price Winter 2016-17 ©2017, AFIO The Bleak Years: 1939 – Mid-1942 GUIDE TO THE STUDY OF INTELLIGENCE The Axis powers repeatedly surprised Poland, Britain, France, and others, who were often blinded by preconceptions and biases, in both a strategic and tactical sense. When war broke out on September 1, 1939, the Polish leadership, ignoring their own intelligence, lacked an appreciation of German mili- tary capabilities: their cavalry horses were no match From Axis Surprises to Allied for German Panzers. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain misread Hitler’s intentions, unwilling to Victories accept the evidence at hand. This was the consequence of the low priority given to British intelligence in the The Impact of Intelligence in World War II period between wars.3 Near the end of the “Phony War” (September 3, 1939 – May 10, 1940) in the West, the Germans engi- By Peter C. Oleson neered strategic, tactical, and technological surprises. The first came in Scandinavia in early April 1940. s governments declassify old files and schol- ars examine the details of World War II, it is Norway Aapparent that intelligence had an important The April 9 German invasion of Norway (and impact on many battles and the length and cost of this Denmark) was a strategic surprise for the Norwegians catastrophic conflict. As Nigel West noted, “[c]hanges and British. -

Duckwitz Die Rettung Der Dänischen Juden the Rescue of the Danish Jews GEORG FERDINAND FERDINAND GEORG

Edition DIPLOMATISCHE Diplomatie PROFILE ISBN 978-3-00-043167-8 DIPLOMATISCHE PROFILE GEORG FERDINAND Duckwitz Die Rettung der dänischen Juden The Rescue of the Danish Jews GEORG FERDINAND FERDINAND GEORG Hans Kirchhoff Hans Kirchhoff Duckwitz Dr. phil. Hans Kirchhoff, geb. 1933, emeritierter Professor am Institut für Geschichte der Universität Kopenhagen. Forschungsschwerpunkte: 2. Weltkrieg, deutsche Besatzung in Dänemark, dänische Flüchtlings- politik 1933–1945, Holocaust. Dr. phil. Hans Kirchhoff, born 1933, Professor emeritus, Institute of History, University of Copenhagen. Main interests: World War II, German occupation of Denmark, Danish refugee policy 1933–1945, Holocaust. Hans Kirchhoff Auszug aus Duckwitz‘ Tagebuch Extract from Duckwitz‘s diary GEORG FERDINAND Duckwitz Die Rettung der dänischen Juden The Rescue of the Danish Jews Hans Kirchhoff Vorwort Preface Staatssekretärin Dr. Emily Haber State Secretary Dr Emily Haber Vor 70 Jahren, Anfang Oktober 1943, unternahm das NS-Regime den Seventy years ago, in early October 1943, the Nazi regime attempted Versuch, die in Dänemark befindlichen Juden als Teil der „End lösung“ to deport Denmark’s Jewish community as part of the “final solution”, zu deportieren. Der verbrecherische Plan scheiterte. Die Masse der the genocide of Europe’s Jews. The heinous plan failed. The majority jüdischen Bevölkerung konnte über den Öresund nach Schweden of the Jewish population were able to flee over the Sound to Swe- fliehen und entkam der Vernichtung. Die Geschichte der „Menschen- den and to escape death. The story of the “human wall” which Danes mauer“, die damals von Dänen um ihre jüdischen Mitbürger errichtet formed around their Jewish compatriots at that time does credit to wurde, gereicht ihnen und Dänemark bis heute zur Ehre. -

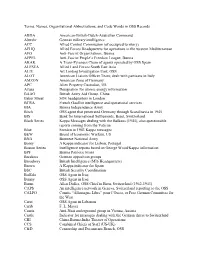

Terms, Names, Organizational Abbreviations, and Code Words in OSS Records

Terms, Names, Organizational Abbreviations, and Code Words in OSS Records ABDA American-British-Dutch-Australian Command Abwehr German military intelligence ACC Allied Control Commission (of occupied territory) AFHQ Allied Forces Headquarters for operations in the western Mediterranean AFO Anti-Fascist Organizations, Burma AFPFL Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League, Burma AKAK A Trans-Pyrenees Chain of agents operated by OSS Spain ALFSEA Allied Land Forces South East Asia ALIU Art Looting Investigation Unit, OSS ALOT American Liaison Officer Team; dealt with partisans in Italy AMZON American Zone of Germany APC Alien Property Custodian, US Azusa Designation for atomic energy information BAAG British Army Aid Group, China Baker Street SOE headquarters in London BCRA French Gaullist intelligence and operational services BIA Burma Independence Army Birch OSS agent that penetrated Germany through Scandinavia in 1945 BIS Bank for International Settlements, Basel, Switzerland Black Series Kappa Messages dealing with the Balkans (1944); also questionable reports coming from the Vatican Blue Sweden in 1943 Kappa messages BEW Board of Economic Warfare, US BNA Burmese National Army Bonty A Kappa indicator for Lisbon, Portugal Boston Series Intelligence reports based on George Wood/Kappa information BPF Burma Patriotic Front Breakers German opposition groups Broadway British Intelligence (MI6 Headquarters) Brown A Kappa indicator for Spain BSC British Security Coordination Buffalo OSS Agent in Iraq Bunny OSS Agent in Iraq Burns Allen Dulles, OSS Chief in Bern, Switzerland (1942-1943) CAPS An intelligence network in Geneva, Switzerland reporting to the OSS CALPO Comite “Allemagne Libre” pour l’Ouest, or Free German Committee for the West Carat OSS Agent in Lebanon Carib F. -

For Foreign Film Producers French Publishers

Couverture FP2S 2011.pdf 1 04/04/11 16:47 FRENCH PUBLISHERS FOR FOREIGN CATALOGUE FILM PRODUCERS C M J AU DIABLE VAUVERT GALAADE ÉDITIONS CM BELFOND HÉLIUM MJ CJ CASTERMAN LE LOMBARD CMJ LE CHERCHE MIDI MAX MILO N DARGAUD MICHALON DELCOURT LE PRÉ AUX CLERCS DENOËL PRESSES DE LA CITÉ r - Relecture Kiki Anderson RelectureKiki - r f . s DUPUIS ROBERT LAFFONT op r d : e FAYARD ÉDITIONS DU ROCHER qu i aph r g on ti a é r C E>L<:M:EH@N>L=N;B>? EDITION 2011 3 ‘From Page to Film’: stories you’ll long to make into movies... With the encouragement of the SCELF, BIEF has published this collective catalogue for foreign producers who are keen to exploit France’s editorial production and would like to discover its diversity. Here is a selection of roughly fifty books whose universe, characters or historical settings provide, in the opinion of the thirty French publishers who chose them, ideal material for cinematic adaptation. Each entry is an invitation to embark on an audiovisual adventure. A contact is given for each book presented: in just a few pages, you’ll find many names to create or complete your address book. We hope this catalogue will be the beginning of many new projects. Enjoy! BIEF 115, boulevard St-Germain 75006 Paris Tel.: +33 (0)1 44 41 13 16 www.bief.org 4 5 ‘I believe that if I love a book, there’s no reason why it shouldn’t make a good film. Similarly, it’s also possible to make a great movie out of a terrible book. -

Eavesdropping on Hell: Historical Guide to Western Communications Intelligence and the Holocaust, 1939-1945 UNITED STATES CRYPTOLOGIC HISTORY

Series IV Volume 9 Eavesdropping on Hell: Historical Guide to Western Communications Intelligence and the Holocaust, 1939-1945 UNITED STATES CRYPTOLOGIC HISTORY Eavesdropping on Hell: Historical Guide to Western Communications Intelligence and the Holocaust, 1939-11945 Robert J. Hanyok CENTER FOR CRYPTOLOGIC HISTORY NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY 2005 Second Edition Table of Contents Page Table of Contents . .iii Preface and Acknowledgments . .1 A Note on Terminology . 5 Acknowledgments . 7 Chapter 1: Background . .11 The Context of European and Nazi Anti-Semitism . .11 Previous Histories and Articles . .14 Chapter 2: Overview of the Western Communications Intelligence System during World War II . 21 Step 1: Setting the Requirements, Priorities, and Division of Effort . .24 Step 2: Intercepting the Messages . .30 Step 3: Processing the Intercept . .36 Step 4: Disseminating the COMINT . .43 From Intercept to Decryption – the Processing of a German Police Message . .51 Chapter 3: Sources of Cryptologic Records Relating to the Holocaust . .61 The National Archives and Records Administration . .61 The Public Record Office . .67 Miscellaneous Collections . .71 Chapter 4: Selected Topics from the Holocaust . .75 A. The General Course of the Holocaust and Allied COMINT . .76 B. Jewish Refugees, the Holocaust, and the Growing Strife in Palestine . .86 C. The Vichy Regime and the Jews . .89 D. The Destruction of Hungary’s Jews, 1944 . .94 E. Japan and the Jews in the Far East . .99 F. Nazi Gold: National and Personal Assests Looted by Nazis and Placed in Swiss Banks, 1943 - 1945 . .104 Chapter 5: Some Observations about Western Communications Intelligence and the Holocaust . .. .121 What was Known from COMINT .