Wonderland Trail Mount Rainier National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mount Rainier National Park

MOUNT RAINIER NATIONAL PARK • WASHINGTON • UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Mount Rainier [WASHINGTON] National Park United States Department of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Arno B. Cammerer, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1936 Rules and Regulations [BRIEFED] Events kjERVING a dual purpose, park regulations are designed for the comfort and convenience of visitors as well as for the protection of natural beauties OF HISTORICAL IMPORTANCE and scenery. The following synopsis is for the guidance of visitors, who are requested to assist the park administration by observing the rules. Complete rules and regulations may be seen at the superintendent's office 1792 May 8. The first white man to sec "The Mountain" (Capt. and at ranger stations. George Vancouver, of the Royal English Navy) sighted Fires. the great peak and named it Mount Rainier. Light carefully and in designated places. Extinguish COMPLETELY before leaving 1833 September 2. Dr. William Eraser Tolmie of Nisqually camp, even for temporary absence. Do not guess your fire is out—KNOW it. Do not House, a Hudson's Bay post, entered the northwest corner throw burning tobacco or matches on road or trail sides. of what is now the park. He was the first white man to penetrate this region. Camps. Keep your camp clean. As far as possible burn garbage in camp fire, and empty 1857 July. Lieut. A. V. Kautz, of the United States Army garri son at Fort Steilacoom, and four companions made the cans and residue into garbage cans provided. If no can is provided, bury the refuse. -

An Inventory of Fish in Streams in Mount Rainier National Park 2001-2003

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science An Inventory of Fish in Streams at Mount Rainier National Park 2001-2003 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCCN/NRTR—2013/717.N ON THE COVER National Park staff conducting a snorkel fish survey in Kotsuck Creek, Mount Rainier National Park, 2002. Photograph courtesy of Mount Rainier National Park. An Inventory of Fish in Streams at Mount Rainier National Park 2001-2003 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCCN/NRTR—2013/717.N Barbara A. Samora, Heather Moran, Rebecca Lofgren National Park Service North Coast and Cascades Network Inventory and Monitoring Program Mount Rainier National Park Tahoma Woods Star Rt. Ashford, WA. 98304 April 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

2010 CENSUS - CENSUS TRACT REFERENCE MAP: Lewis County, WA 121.217411W LEGEND Emmons Glacier

46.862203N 46.867049N 121.983702W 2010 CENSUS - CENSUS TRACT REFERENCE MAP: Lewis County, WA 121.217411W LEGEND Emmons Glacier Y P SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL LABEL STYLE South Mowich Fryingpan Glacier A I Glacier E K R I C M Federal American Indian Puyallup Glacier E A Reservation L'ANSE RES 1880 0 Bumping Lk Ingraham Glacier 5 0 3 7 7 Off-Reservation Trust Land, Hawaiian Home Land T1880 Tahoma Glacier Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area, Alaska Native Village Statistical Area, KAW OTSA 5340 Tribal Designated Statistical Area State American Indian W Tama Res 4125 ilson Glacier Reservation Kautz Glacier South Tahoma Glacier Nisqually Glacier Cowlitz Glacier State Designated Tribal Statistical Area Lumbee STSA 9815 Alaska Native Regional Corporation NANA ANRC 52120 State (or statistically equivalent entity) NEW YORK 36 County (or statistically Mount Rainier Natl Pk equivalent entity) ERIE 029 Minor Civil Division (MCD)1,2 Bristol town 07485 123 PIERCE 053 Consolidated City MILFORD 47500 S LEWIS 041 d R lley 1,3 Va e Incorporated Place s Davis 18100 i rad Pa Census Designated Place (CDP) 3 Incline Village 35100 ns Cany e on v e R t d S Census Tract 33.07 706 DESCRIPTION SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL Interstate 3 Water Body Pleasant Lake W o l d 706 706 r o 2 R 2 F 1 U.S. Highway 0 e Cre d t at ek a d Swamp or Marsh Okefenokee Swamp Sk N N R R i v d sq e N u D ally Riv State Highway 4 Glacier Bering Glacier 4 Marsh Ln 4 Other Road N d D a R e t v F v or Na e R t D d F 4WD Trail, Stairway, 0 o r 1 r o 2 F Military Fort Belvoir D e t Alley, Walkway, -

Shriner Peak Fire Lookout 03/13/1991

6/B2 National Park Service Westin Buildingding, 0^^920 I Aveni^^ WRO Pacific Northwest Region 2001 Sixth 1 SITE I D. NO INVENTORY Cultural Resources Division Seattle, Washington 98121 2 NAME(S) OF STRUCTURE (CARD 1 of 2) 5. ORIGINAL USE 7. CLASSIFICATION Shriner Peak Fire Lookout Fire Lookout 1932 3 SITE ADDRESS (STREET A NO) 6. PRESENT USE Fire Lookout Shriner Peak 0-052 and BackcounTi EASTING try Assistance COUNTY STATE SCALE 4 CITY/VICINITY 1 24 QUAD Ohanapecosh Lewis Washington OTHER , .NAME. 12 OWNER/AOMIN ADDRESS NPS/Mount Rainier National Park, Tahonia Woods-Star Route^ Ashford, WA., 98304 n ni r;rMiiMK)N and nACKr'.nnuNf) iiiruonv includini; crjN.-.mufuioN daims), mvsicAi oiMt nsions. maifmiai s, ma.kir ai ifraiions. fxiant f.ouipmfni. and IMPOniANI DUILDEHS. AMCMirFCrS. ENOINEERS. EIC Timber frame, two-story, square plan; hip roof, cedar shingles, projecting eaves; wrap around balcony, fixed sashes, rough lapped (Douglas Fir) exterior siding; wood floors, tongue-and-groove interior walls and ceilings; concrete foundation. In 1931 Superintendent O.A. Tomlinson reported that three fire lookouts were being manned by park personnel; Colonnades, Anvil Rock and Shriner Peak. Althdugh it is not known what kind of lookout existed then on Shrlner Peak, in 1932 a private contractor (engaged in road construction on the East Side Road) erected a new timber frame lookout. Measuring 14' X 14', it was built according to a standard design drafted by the National Park Service, Landscape Division (Branch of Plans and Design) in 1932. Thomas E. Carpenter, Landscape Architect recommended the design. Typically, the ground floor was used for storage and the one-room upper floor contained the fire finder, charts, supplies, a bed and cooking facilities. -

Carbon River Access Management Plan

United States Department of the Interior FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Washington Fish and Wildlife Office 510 Desmond Dr. SE, Suite 102 Lacey, Washington 98 503 APR 2 6 20ll In Reply Refer To: 13410-2010-F-0488 Memorandum To: Superintendent, Mount Rainier National Park Ashford, Washington From: Manager, Washington Fish and Wildlife Lacey, Washington Subject: Biological Opinion for the Carbon River Access Management Plan This document transmits the Fish and Wildlife Service's Biological Opinion based on our review of the proposed Carbon River Access Managernent Plan to be implemented in Mount Rainier National Park, Pierce County, Washington. We evaluated effects on the threatened northern spotted owl (Sfrlx occidentalis caurina),marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus),bttll trout (Salvelinus confluentus), and designated bull trout critical habitat in accordance with section 7 of the Endangered Species Act (Act) of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.). Your July 29,2010 request for formal consultation was received on August 2,2010. This Biological Opinion is based on information provided in the June 28, 2010 Biological Assessment and on other information and correspondence shared between our respective staff. Copies of all correspondence regarding this consultation are on file at the Washington Fish and Wildlife Office in Lacey, Washington. If you have any questions about this mernorandum, the attached Biological Opinion, or your responsibilities under the Act, please contact Vince Harke at (360) 753-9529 or Carolyn Scafidi at (360) 753-4068. Endangered Species Act - Section 7 Consultation BIOLOGICAL OPINION U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Reference: 13410-2010-F-0488 Carbon River Access Management Plan Mount Rainier National Park Pierce County, Washington Agency: National Park Service Consultation Conducted By: U.S. -

Mount Rainier National Park, Washington

NATIONAL PARK . WASHINGTON MOUNT RAINIER WASHINGTON CONTENTS "The Mountain" 1 Wealth of Gorgeous Flowers 3 The Forests 5 How To Reach the Park 8 By Automobile 8 By Railroad and Bus 11 By Airplane 11 Administration 11 Free Public Campgrounds 11 Post Offices 12 Communication and Express Service 12 Medical Service 12 Gasoline Service 12 What To Wear 12 Trails 13 Fishing 13 Mount Rainier Summit Climb 13 Accommodations and Expenses 15 Summer Season 18 Winter Season 18 Ohanapecosh Hot Springs 20 Horseback Trips and Guide Service 20 Transportation 21 Tables of Distances 23 Principal Points of Interest 28 References 32 Rules and Regulations 33 Events of Historical Importance 34 Government Publications 35 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR • Harold L. Ickes, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Arno B. Cammerer, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE • 1938 AN ALL-YEAR PARK Museums.—The park museum, headquarters for educational activities, MOUNT RAINIER NATIONAL PARK may be fully enjoyed throughout the and office of the park naturalist are located in the museum building at year. The summer season extends from early June to early November; the Longmire. Natural history displays and wild flower exhibits are main winter ski season, from late November well into May. All-year roads make tained at Paradise Community House, Yakima Park Blockhouse, and the park always accessible. Longmire Museum. Nisquaiiy Road is open to Paradise Valley throughout the year. During Hikes from Longmire.—Free hikes, requiring 1 day for the round trip the winter months this road is open to general traffic to Narada Falls, 1.5 are conducted by ranger naturalists from the museum to Van Trump Park, miles by trail from Paradise Valley. -

Concept of Operations for Mount Rainier National Park Intelligent Transportation Systems Mount Rainier National Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Concept of Operations for Mount Rainier National Park Intelligent Transportation Systems Mount Rainier National Park Natural Resource Report NPS/NRR—2013/04 NPS D-XXX/XXXXXX & PMIS 88348 ON THE COVER Highway Advisory Radio Information Sign, Mount Rainier National Park Photograph by: Steve Lawson Concept of Operations for Mount Rainier National Park Intelligent Transportation Systems Mount Rainier National Park Natural Resource Report NPS/NRR—2013/04 NPS D-XXX/XXXXXX & PMIS 88348 Lawrence Harman1, Steve Lawson2, and Brett Kiser2 1Harman Consulting, LLC 13 Beckler Avenue Boston, MA 02127 2Resource Systems Group, Inc. 55 Railroad Row White River Junction, VT 05001 April 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

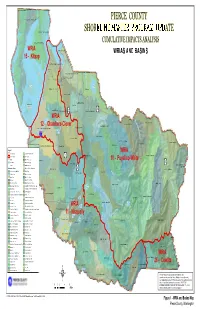

Pierce County Shoreline Master Program Update

Key Peninsula-FrontalKey Peninsula-Frontal Case Inlet Case Inlet Key Peninsula-Frontal Carr Inlet PIERCE COUNTY Key Peninsula-Frontal Carr Inlet PIERCE COUNTY SHORELINE MASTER PROGRAM UPDATE Curley Creek-Frontal Colvos Passage SHOR LINE MA PR AM U DATE Curley Creek-Frontal Colvos Passage Burley Creek-Frontal Carr Inlet CUMULATIVERESTORATION IMPACTS PLAN ANALYSIS Burley Creek-Frontal Carr Inlet WRIAWRIA MillerMiller Creek-Frontal Creek-Frontal East PassageEast Passage WRIASWRIASWRIAS A ANDND B BASINS BASINSASINS 1515 - -Kitsap Kitsap City ofCity Tacoma-Frontal of Tacoma-Frontal Commencement Commencement Bay Bay White R FOX Whit FOX HylebosHylebos Creek-Frontal Creek-Frontal Commencement Commencement Bay Bay ISLANDISLAND eR iv i ver e Lake MC NEILMC NEIL r Lake TappsTapps ISLANDISLAND Chambers Creek - Leach Creek Chambers Creek - Leach Creek WhiteWhite River River D D N N SwanSwan Clear Clear Creeks Creeks U U O O S S PuyallupPuyallup Shaw Shaw Road Road Upper Upper AndersonAnderson Island Island ClarksClarks Creek Creek ANDERSONANDERSON e RRi hhi it t e ivveerr ISLANDISLAND WW CloverClover Creek Creek - Lower - LowerClover Creek - North Fork ?¨ Clover Creek - North Fork?Ã FennelFennel Creek-Puyallup Creek-Puyallup River River ?¨ T T ?Ã E E G rGer e e e G G WRIA ri rei eCCr n n WRIA r i eeeek U American a i k w w U American r a CC a a Spa S r l P P Lake Lake na pana P P l ee t t w w Twin Creek-White River e e a a o v e v e t h h aa Twin Creek-White River y C l l or r t r r r C y C Boise Creek-White River River r C C u u ww r C r e e o South -

Debris Properties and Mass-Balance Impacts on Adjacent Debris-Covered Glaciers, Mount Rainier, USA

Natural Resource Ecology and Management Publications Natural Resource Ecology and Management 4-8-2019 Debris properties and mass-balance impacts on adjacent debris- covered glaciers, Mount Rainier, USA Peter L. Moore Iowa State University, [email protected] Leah I. Nelson Carleton College Theresa M. D. Groth Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/nrem_pubs Part of the Environmental Monitoring Commons, Glaciology Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, and the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons The complete bibliographic information for this item can be found at https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ nrem_pubs/335. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resource Ecology and Management at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Resource Ecology and Management Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Debris properties and mass-balance impacts on adjacent debris-covered glaciers, Mount Rainier, USA Abstract The north and east slopes of Mount Rainier, Washington, are host to three of the largest glaciers in the contiguous United States: Carbon Glacier, Winthrop Glacier, and Emmons Glacier. Each has an extensive blanket of supraglacial debris on its terminus, but recent work indicates that each has responded to late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century climate changes in a different way. While Carbon Glacier has thinned and retreated since 1970, Winthrop Glacier has remained steady and Emmons Glacier has thickened and advanced. -

Geology, Published Online on 24 May 2011 As Doi:10.1130/G31902.1

Geology, published online on 24 May 2011 as doi:10.1130/G31902.1 Geology Whole-edifice ice volume change A.D. 1970 to 2007/2008 at Mount Rainier, Washington, based on LiDAR surveying T.W. Sisson, J.E. Robinson and D.D. Swinney Geology published online 24 May 2011; doi: 10.1130/G31902.1 Email alerting services click www.gsapubs.org/cgi/alerts to receive free e-mail alerts when new articles cite this article Subscribe click www.gsapubs.org/subscriptions/ to subscribe to Geology Permission request click http://www.geosociety.org/pubs/copyrt.htm#gsa to contact GSA Copyright not claimed on content prepared wholly by U.S. government employees within scope of their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted permission, without fees or further requests to GSA, to use a single figure, a single table, and/or a brief paragraph of text in subsequent works and to make unlimited copies of items in GSA's journals for noncommercial use in classrooms to further education and science. This file may not be posted to any Web site, but authors may post the abstracts only of their articles on their own or their organization's Web site providing the posting includes a reference to the article's full citation. GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, regardless of their race, citizenship, gender, religion, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this publication do not reflect official positions of the Society. Notes Advance online articles have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet appeared in the paper journal (edited, typeset versions may be posted when available prior to final publication). -

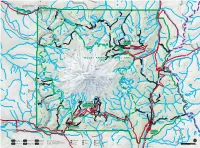

Moramap1.Pdf

To Wilkeson 13mi / 21km from CLEARWATER Carbon River Entrance k Obtain Climbing and Wilderness Road closed to vehicles beyond e this point. Road open to foot WILDERNESS e Camping Permits for the northwest r and bicycle traffic. Bicyclists must C r area of the park at Carbon River remain on the main road. e v Carbon e i Ranger Station. MT. BAKER-SNOQUALMIE NATIONAL FOREST o D R 165 rbon River T Ca rail (former road) r r 4mi e e C v Carbon River Entrance 6km i G v Chenuis Falls E i h e 410 R o G Lake t 1880ft k R e Carbon River i a e 573m n D e t I Eleanor e h u t Carbon River Rainforest Trail r R i k Tirzah Peak i C s h W e J 5208ft Scarface u e Adelaide Pigeon Peak r W E k n C 1587m 6108ft e L o C Lake e E k 1862m re C s N Oliver r r C Wallace Peak C A t e E e C G Ranger Falls o Sweet H Lake d k r F E D D a Peak e I N N e U ls t R I E s k l S Marjorie e a C P F Slide Mountain r E W T Lake C M e Green D 6339ft 2749ft N46° 58´ 42˝ S r Ipsut Creek O e e N 1932m 838m U Lake k I U e W121° 32´ 07˝ Florence Peak N Chenuis y R r C T Cr r k 5508ft e a A r A rb B e L 1679m g o EE I N Lakes rn n n F o b K Arthur Peak LA e I a T Lake H l Gove Peak S 5483ft R n k i C NORTH C l 5310ft Ethel a c v R 1671m u J r e E PARK 1619m W R V o e r iv H s S o e T n e ep r k de Lake K h k rl R in BURNT e an James A e C Howard Peak e d Y P PARK r r E Tyee Peak C LL e 5683ft Tr OW Natural D e ail S S k NORSE PEAK 1732m Spukwush TONE CLIFF Bridge N Tolmie Peak t C A u r Redstone R 5939ft s Alice e G p e Peak C 1810m I Falls k re BEAR e Norse Peak k WILDERNESS Eunice -

MOUNT • RAINIER NATIONAL • PARK Wbtm

wBtmmm wcy«yS&jfli .V&2Smmmmmmm\ fmWk\ mmmWmZfWmVWm W&* M §?'/*£¥&LWrnA Ur+Jmmmm m$af •5-t'' s '•* f •' •' '• Jvfl MOUNT • RAINIER NATIONAL • PARK r~Wask inatopis Trail Guide MOUNT RAINIER NATIONAL PARK Washington This Trail Guide is printed in such a way that the Wonderland Trail Section 1 is the Carbon River area. By starting a trip in this section of the park (such as the one around Mount Rainier on the Wonderland Trail) the hiker may come out periodically at devel oped areas, such as Longmire or Yakima Park, to renew supplies or to dry off if the weather has been wet. However, the hiker may begin long trips anywhere, or short trips as he pleases, by noting the maps in this trail guide and the descriptions of the vari ous trails in each sec tion. 1 SECTION 1 about 50 feet in a setting of trees, "coasting" and the Mowich Lake Carbon River WONDERLAND TRAIL ferns, and moss-covered rocks. Trail intersection is reached. It is Up again out of the trees and into four-tenths of a mile from here to the sunshine of the alpine meadows beautiful Mowich Lake, which oc is a land of flowers and cool, pure cupies an old glacial cirque and is Summary of Trail head wall of a glacial cirque of water. Here are miles of open the largest body of water in Mount Mileages such enormous proportions as to trail through Seattle and Spray Rainier National Park. Mowich is stagger the imagination. At its Parks. In a few spots the trail a Chinook Indian word meaning There are 26.3 miles of the Wonder feet begin the ice masses of the Car reaches rocky country, snowfields, "deer." land Trail in this section of the park.