The Role of Major Events in the Creation of Social Legacy: a Case Study of the Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Perspective 2

Economic Perspective 2 THE GLASGOW GARDEN FESTIVAL: MAKING GLASGOW MILES BETTER? John Heeley and Mike Pearlman Scottish Hotel School, University of Strathlcyde INTRODUCTION and/or existing parkland is refurbished in order to mount major exhibitions of plants. The The Glasgow Garden Festival (GGF) opened its gates festival's duration is normally six months in to the general public on April 28, 1988 and order to allow the changing seasons to be mirrored represented a crucial step in Glasgow's in floral displays. The exhibitions are then development as a tourism destination. The removed, leaving the upgraded land for future Festival, alongside Glasgow's designation as the development. European City of Culture in 1990 can be seen as the basis of a strong events-led tourism Despite the widespread popularity of gardening in development strategy. The sponsors and organisers Britain, it is only recently that serious of the Festival had set a target of 3 million attention has been paid to the garden festival visitors through the gates by the time the concept in the UK. There are some historical Festival closed on September 26, 1988. In fact, pointers in that Britain did pioneer trade the Festival has achieved a throughput of 4.25 exhibitions, beginning with the Great Exhibition million people. of 1851 at Crystal Palace which attracted over 6 million visitors. The Festival of Britain held in The GFF is essentially a tool for urban London in 1951 commemorated the 100th anniversary regeneration and the site's after-use will be of the Great Exhibiton and had a major leisure closely monitored given the difficulties faced by component (situated in Battersea park) including previous festival sites at Stoke and Liverpool in a giant rubber Octopus. -

City of Art“: Evaluating Singapore's Vision Of

CREATING A “CITY OF ART”: EVALUATING SINGAPORE’S VISION OF BECOMING A RENAISSANCE CITY by LEE, Wai Kin Bachelor of Arts (Honors) Geography National University of Singapore, 2000 Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN URBAN STUDIES AND PLANNING at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2003 © 2003 LEE, Wai Kin. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author:________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning August 19, 2003 Certified by:_______________________________________________________ J. Mark Schuster Professor of Urban Cultural Policy Thesis Supervisor Accepted by:______________________________________________________ Dennis Frenchman Chair, Master in City Planning Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning CREATING A “CITY OF ART”: EVALUATING SINGAPORE’S VISION OF BECOMING A RENAISSANCE CITY by LEE, Wai Kin Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on August 19, 2003 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Urban Studies and Planning ABSTRACT The arts have been used by many cities as a way to regenerate their urban environments and rejuvenate their economies. In this thesis, I examine an approach in which city-wide efforts are undertaken to create a “city of art”’. Such attempts endeavor to infuse the entire city, not just specific districts, with arts and cultural activities and to develop a strong artistic inclination among its residents. Singapore’s recent plan to transform itself into a “Renaissance City” is an example of such an attempt to create a “city of art”. -

Clyde Waterfront Green Network

Clyde Waterfront is a public sector partnership established to promote and facilitate the implementation of the River Clyde's regeneration as a world class waterfront location. The project will be a key driver of Scotland's economic development in the 21st century. A 15 year plan has been developed to transform the environment, communities, transport infrastructure and economy along the river from Glasgow to Erskine Bridge in the largest project of its kind to be undertaken in Scotland. The partnership involves the Scottish Executive, Glasgow City Council, Renfrewshire Council, West Dunbartonshire Council, Scottish Enterprise and Communities Scotland. The Green Network Strategy has been developed with the additional support of SNH and Forestry Commission Scotland. Visit www.clydewaterfront.com for further information. CONTENTS Part 1 - Strategic Overview of the Clyde Green Network Introduction ..........................................................................................................................................................................................3 Key gaps and opportunities for the Clyde Waterfront Green Network.................................................................................................5 Area wide priorities for delivering the green network.........................................................................................................................18 Next steps ..........................................................................................................................................................................................20 -

SB-4110-April

the www.scottishbanner.com Scottishthethethe Australasian EditionBanner 37 Years StrongScottishScottishScottish - 1976-2013 Banner A’BannerBanner Bhratach Albannach 42 Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Years Strong - 1976-2018 www.scottishbanner.com A’ Bhratach Albannach Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 VolumeVolumeVolume 41 36 36 NumberNumber Number 1011 11 The The The world’s world’s world’s largest largest largest international international international Scottish ScottishScottish newspaper newspaper newspaper May May April 2013 2013 2018 Team Scotland at the Gold Coast Commonwealth Games » Pg 14 Bringing tartan to the world Siobhan Mackenzie » Pg 16 Glasgow’s Great US Barcodes Garden Gala » Pg 10 Flowering 7 25286 844598 0 1 of Scotland! The Scottish daffodil » Pg 30 7 Australia25286 84459 $4.00 8 $3.950 9 CDN $3.50 US N.Z. $4.95 The Whithorn Way - Stepping in the ancient footsteps of Scotland’s pilgrims ................................. » Pg 8 Muriel Spark - 100 Years of one of Scotland’s greatest writers ............ » Pg 27 7 25286 844598 0 3 The Cairngorm Creature - The Big Grey Man of Ben Macdhui ............... » Pg 31 7 25286 844598 1 1 7 25286 844598 1 2 THE SCOTTISH BANNER Scottishthe Volume Banner 41 - Number 10 The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Publisher Valerie Cairney Editor Sean Cairney The Tartan Revolution EDITORIAL STAFF Jim Stoddart Ron Dempsey, FSA Scot The National Piping Centre David McVey Angus Whitson Lady Fiona MacGregor A month for tartan to shine Marieke McBean David C. -

Mavisbank Gardens | Festival Park | Glasgow| G51

Mavisbank Gardens | Festival Park | Glasgow| G51 1HL Modern one bedroom apartment within the Festival Park development which has a aspect views overlooking River Clyde. Mavisbank Gardens Modern one bedroom apartment within the Festival Park development which has a aspect views overlooking River Clyde. • Spacious living room with • Private Parking river views • Secure Video Door Entry • Modern Kitchen with • Residents’ Gardens integrated appliances • Double Sized Bedroom with storage Description The building is entered through a secure door entry system which leads to the property on the first floor. The accommodation consists of reception hallway with storage off, spacious living room with views over the River Clyde, modern kitchen with integrated appliances and fitted kitchen units. Double sized bedroom with walk-in wardrobe storage and to complete the accommodation there is a three piece suite bathroom. The property further benefits include double glazed window units, private parking and resident’s gardens. Extras: Other than the integrated kitchen appliances, only items specifically mentioned in the particulars of sale are included in the sale price unless otherwise agreed in offer. The property is supplied by water, electricity and drainage. Local Authority: Glasgow City Council Property Factor: Speirs Gumley, 194 Bath Street, Glasgow G2 4LE, 0141 332 9225 Kitchen 6’8 x 14’5 Lounge 10’8 x 19’3 (max) Ent Hall W St Bedroom 11’2 x 9’11 Bathroom (at widest point) Floor plans are indicative only - not to scale. Viewing By appointment with D.J. Alexander Legal, 49A Bath Street, Glasgow, G2 2DL. Telephone 0141 333 1345 or email [email protected]. -

Economic Perspective 1

Economic Perspective 1 THE GLASGOW GARDEN FESTIVAL: A WIDER PERSPECTIVE Pam Castledine and Kim Swales Department of Economics, University of Strathclyde The 1988 Glasgow Garden Festival which opened on earlier, events. The Third Reich has been 28 April is and ran for 5 months. It was credited with the revival of such events through located on the 100 acre Princes Dock site in the the 1938 Garden Show held in Essen which extended Govan/Kinning Park area of the city, on the south Gruga Park, but most authorities agree that the bank of the River Clyde, opposite the Scottish present form of Bundesgartenshau arose from the Exhibition and Conference Centre. Preparations 1951 Hanover Show (Bareham, 1983). Between 1951 for the Festival included the clearing of decayed and 1988, 19 such events have been held and future warehouses and ship repair buildings followed by shows are planned in Frankfurt (1989) and the importation of thousands of tons of soil plus Stuttgart (1993) (Golletz, 1985). more than 300,000 trees and shrubs. The total cost of creating and running the Festival is now Similar shows to the German Bundesgartenshau have put at £41.4 million whilst the estimated net cost been held in other European and overseas countries is £18.7 million (dependent upon the number of including Switzerland, Holland, Austria and Canada visitors). The need to maximise the Festival's while Italy and Belgium have held indoor shows. appeal in order to attain the required number of The first Garden Exhibition to be held in a visitors has led to spending of around £2 million tropical country will take place in Singapore in on various forms of advertising, including 1989. -

Let's Go Walking SECC

Life is busy, time is precious. But taking 30 Go on, get to your nearest Walking Hub minutes for a walk will help you feel better – Walk the Walk! Challenge yourself – mentally and physically. Even 15 minutes to ‘give it a go’. Grab a friend, grab your will have a benefit, when you can’t find the children and get outdoors! time to do more. Walking helps you feel more energetic and more able to deal with the Here is a handy little table to get you business of life! Walking also helps us to get started during the first few weeks of fitter and at the same time encourages us to walking. Simply mark on the table get outdoors – and it’s right on your doorstep! which Medal Route you walked on which day – can you build up to Gold? At this Walking Hub you will find 3 short circular walks of different lengths – Bronze, Silver & Gold Medal Routes. You don’t need Week Route M T W T F S S any special equipment to do these walks and going for a walk just got easier they are all planned out on paths – see the 1 map and instructions on the inside. Simple pleasures, easily found Let’s go walking Walking & talking is one of life’s simple 2 pleasures. We don’t need to travel far, we can SECC visit green spaces where Ramblers Scotland we live, make new friends, 3 Medal Routes is a Ramblers Scotland project. Ramblers have been promoting walking and representing the interests of see how things change walkers in England, Scotland and Wales since 1935. -

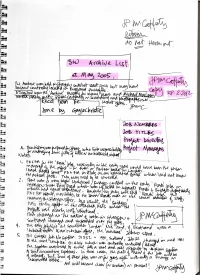

SW History Doc 13 Appx 1 02 Project List 1960-2005.Pdf

r ^^OMKK tUiN V ^-e^. 5; YEAR JOB PROJECT PD PM ARCH " ACTION 3' YEAR 60040 TOWNHEAD INTERCHANGE STAGER; 63040 WOODSIDE MOTORWAY STAGEjy' Q7" 9?-99 64010 EDINBURGH SURVEYS "7 64040 95 GLASGOW INNER RING ROAD - WOODSIDE SECTION (j^ 69029 CONTRACT FOR GROUND INVESTIGATION 71501 GLASGOW CHS ?5 71502 TOWNHEAD INTERCI yGE STAGE 1 71503 WOODSIDE 5$ 71504 RUTHERGLEN - MILL'STfeEi?STRE T PLAN 71505 MOTHERWELL CENTRAL AREA STUDY 71506 RENFREW MOTORWAY STAGE 1 J^V^ / 71507 CLYDEBANK CANAL CLOSURE 95 71508 ST GEORGE'S CROSS COMMERCIAL CENTRE 9? 71509 MOTHERWELL CONTINUATION STUDY 71510 ABERDEEN CENTRAL AREA STUDY 71511 BRANDON STREET BY-PASS MOTHERWELL 71512 STRATHCLYDE UNIVERSITY DEVELOPMENT 71513 RUTHERGLEN - REALIGNMENT MILL STREET - DESIGN 3W 71514 GGTS FOLLOW-UP STUDY A/4 71515 28 BRANDON STREET HAMILTON 71516 ST ANDREWS BY THE GREEN CHURCH 511 71517 BEARSDEN SHOPPING CENTRE - PUBLIC INQUIRY 71518 ST ENOCH STATION REDEVELOPMENT 71519 MOTHERWELL - PUBLIC INQUIRY 71520 COUNTY OF LANARK REDEVELOPMENT - STONEHOUSE 71521 MOTHERWELL CENTRAJTRAIL CDA NO 1 71522 AYR MOTORWAY / T>UMAbviki>^E<A UwVVMtOn 71523 HOUSING - CALDER STREET AREA - ROAD LINE STUDIES 71524 TOWNHEAD INTERCHANGE STAGE 11 71525 MOUNDINAR BURN - SITE INVESTIGATION _2£ 71526 WEST HAMILTON STREET UNDERPASS 71527 PROPOSED RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT GARTCOSH 71528 BEA HELICOPTER HANGAR DYCE AIRPORT ABERDEEN 71529 CLARKSTON INVESTIGATION - GAS COUNCIL INQUIRY hJP> 71530 PARTICK CDA 71531 MELBOURNE - STRATEGY STUDY 71532 MOTHERWELL CDA NO 1 - DIVERSION OF SERVICES 72501 GLASGOW CDA 91 72502 -

Regeneration-Led Culture: Cultural Policy in Glasgow 1970-1989

Edwards, Clare (2018) Regeneration-led culture: cultural policy in Glasgow 1970-1989. PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/71938/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Regeneration-Led Culture: Cultural Policy in Glasgow 1970-1989 Clare Edwards BA (Hons) Fine Art, Newcastle University MA History of Art, The Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the University of Glasgow AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Award with Glasgow Life, conducted through the Centre for Cultural Policy Research, School of Culture and Creative Arts, College of Arts, University of Glasgow July 2018 © Clare Edwards 2018 2 ABSTRACT 1990 is significant as the year in which Glasgow hosted the European City of Culture (ECOC), the first UK city and first ‘post-industrial’ city to do so. Glasgow has subsequently been regarded as constituting a ‘model’ of culture-led regeneration. While much has been written about the impacts of ECOC 1990, comparatively little is known about the emergence of cultural policy in Glasgow in the decades leading to 1990. -

Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Open University for the Degree of Master of Philosophy

qo - lo?z- rvr nn oenB¡n¡UU C- Bound by 10237017 Abbey Bookbinding Co.. otoolor Cordiff Uc 5' lel: (0222) 395882 Fol.t<027'21223345 lilll ll I lt r r ilililllilt il il]t 1ilil È .t r1, .{ ìI THE IMPACT OF GARDEN FESTIVAT WALES ON THE LOCAL TOURISM INDUSTRY FIONA ]AYNE WILLIAMS A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Open University for the degree of Master of PhilosoPhY LL)r[Luau¿ (ct-a't+) February 1994 Ca¡diff Institute of Higher Education DECLARATION I hereby declare that this dissertation is the result of my own work and that due reference is made where necessary to the work of other researchers and authors' I further declare that this disserbation has not beeir accepted in substance for any former degree and is not currentlY submitted in candidature for any other degree. C-andidate Supervisor ,rl1 LU,-tltaL¡¿ -/"^À¿ Fiona J Williams e P#,8¿"47 Director of Studies Supervisor C L DrJ Evans Dr D Botterill ABSTRACT by the Government as The concept of the garden festival was introduced to Britain part of the problems. have varie basic parameters as stated bY the D considerations' 'l'his accorded to each festival haíe diffe local some of the objectives of thesis describes attempts to determine the of company, Garden Ga¡den Festival wales held at Ebbw vale in 1992. The Festival image of the area, which in Festival wales Limited, placed priority on improving the Therefore, it is turn would act as a ffiur for more rápid economic regeneration' postulated in this study that Garden Festival W numbers attributable to the event would have a tourism industry. -

The New Urban Environment of Twentieth Century Britain

Pilot Zones: The New Urban Environment of Twentieth Century Britain By Sam Potter Wetherell A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor James Vernon, Chair Professor Thomas Laqueur Professor Robin Einhorn Professor Theresa Caldeira Spring 2016 Pilot Zones: The New Urban Environment of Twentieth Century Britain © 2016 by Sam Wetherell Abstract Pilot Zones: The New Urban Environment of Twentieth Century Britain by Sam Wetherell Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor James Vernon, Chair In the last third of the twentieth century, Britain underwent an urban transformation that was faster and more profound than any since the industrial revolution. Modernist housing schemes became gated communities. State managed shopping precincts became private out-of-town shopping malls. Derelict docklands became “enterprise zones” for fostering the financial service industry. A material world built from concrete began to give way to a world made of steel and glass. Using material from archives across Britain this dissertation discusses the role played by cities in producing, reflecting, and normalizing Britain’s post-social democratic settlement. The phrase “pilot zones” refers to the five spaces that act as case studies for this dissertation. The first of these two were policies. Enterprise zones, created by the Conservative government in 1981, were miniature tax havens in inner city areas, while National Garden Festivals were ambitious, state-directed garden shows in derelict urban areas that aimed to attract capital for urban redevelopment. -

Clyde Waterfront Green Network Strategy 1

CLYDE WATERFRONT GREEN NETWORK STRATEGY 1 Clyde Waterfront Green Network Strategy 2 CLYDE WATERFRONT GREEN NETWORK STRATEGY 3 Contents 01 Introduction 02 Context 03 Methodology 04 Network Characteristics 05 Strategic Framework 06 Proposed Projects 07 Delivery and Implementation 08 Next Steps 4 “ The Green Network is an ambitious 20 year programme, which will link parks, walkways, woodlands and countryside along miles of path and cycle routes bringing 01 a range of social, economic and environmental benefits Introduction to the Glasgow Metropolitan Region. Our Vision is for a transformed environment which improves lives and communities and lets business flourish.” Glasgow Clyde Valley Green Network Partnership CLYDE WATERFRONT GREEN NETWORK STRATEGY 5 River Clyde Understanding the Green Network The Green Network approach seeks to create Understanding these benefits drives identification incidental spaces within built up areas. They a series of connected, complimentary and of opportunities for and delivery of change in the can and should provide for a range of functions high quality greenspaces across the Glasgow short, medium and long term. Green Networks can encompassing wildlife havens, recreation and Metropolitan Region. help to; cultural experiences, organised sport and informal amenity/play. They operate at all spatial levels, The concept of Green Networks advocates a • Encourage stronger communities by creating from small scale spaces in urban centres, through joined-up approach to environmental management: places to be proud of suburban