9 Keys to Staying in the Race Jonathan Beverly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDIA INFO & Fast Facts

MEDIAWELCOME INFO MEDIA INFO Media Info & FAST FacTS Media Schedule of Events .........................................................................................................................................4 Fact Sheet ..................................................................................................................................................................6 Prize Purses ...............................................................................................................................................................8 By the Numbers .........................................................................................................................................................9 Runner Pace Chart ..................................................................................................................................................10 Finishers by Year, Gender ........................................................................................................................................11 Race Day Temperatures ..........................................................................................................................................12 ChevronHoustonMarathon.com 3 MEDIA INFO Media Schedule of Events Race Week Press Headquarters George R. Brown Convention Center (GRB) Hall D, Third Floor 1001 Avenida de las Americas, Downtown Houston, 77010 Phone: 713-853-8407 (during hours of operation only Jan. 11-15) Email: [email protected] Twitter: @HMCPressCenter -

Norcal Running Review

The Northern California Running Review, formerly the West Ramirez. Juan is a freshman at San Jose City College and lives Valley Newsletter. is published on a monthly basis by the West at 64.6 Jackson Ave., San Jose, 95116 (Apt. 9) - Ph. 258-9865. Valley Track Club of San Jose, California. It is a communica- At 19, Juan has best times of 1:59.7, 4:28.3, and 9:51.7. He tion medium for all Northern California track and field ath- ran 19:45 for four miles cross country this past season, and letes, including age group, high school, collegiate, AAU, women, was a key factor in SJCC's high ranking in Northern California, and senior runners. The Running Review is available at many road races and track meets throughout Northern California for Some address changes for club members: Rene Yco has moved 25% an issue, or for $3-50 per year (first class mail). All to 1674 Adrian May, San Jose, 95122 (same phone); Sean O'Rior- West Valley TC athletes receive their copies free if their dues dan is now attending Washington State Univ. and has a new ad- are paid up for the year. dress of Neill Hall, %428, WSU, Pullman, Wash., 99163; Tony Ca sillas was inducted into the armed forces in February and can This paper's success depends on you, the readers, so please be reached (for a while anyway) by writing Pvt. Anthony Casillas, send us any pertinent information on the NorCal running scene (551-64-9872), Co. A BN2 BDE-1, Ft. -

6 World-Marathon-Majors1.Pdf

Table of contents World Marathon Majors World Marathon Majors: how it works ...............................................................................................................208 Scoring system .................................................................................................................................................................210 Series champions ............................................................................................................................................................211 Series schedule ................................................................................................................................................................213 2012-2013 Series results ..........................................................................................................................................214 2012-2013 Men’s leaderboard ...............................................................................................................................217 2012-2013 Women’s leaderboard ........................................................................................................................220 2013-2014 Men’s leaderboard ...............................................................................................................................223 2013-2014 Women’s leaderboard ........................................................................................................................225 Event histories ..................................................................................................................................................................227 -

Updated 2019 Completemedia

April 15, 2019 Dear Members of the Media, On behalf of the Boston Athletic Association, principal sponsor John Hancock, and all of our sponsors and supporters, we welcome you to the City of Boston and the 123rd running of the Boston Marathon. As the oldest annually contested marathon in the world, the Boston Marathon represents more than a 26.2-mile footrace. The roads from Hopkinton to Boston have served as a beacon for well over a century, bringing those from all backgrounds together to celebrate the pursuit of athletic excellence. From our early beginnings in 1897 through this year’s 123rd running, the Boston Marathon has been an annual tradition that is on full display every April near and far. We hope that all will be able to savor the spirit of the Boston Marathon, regardless whether you are an athlete or volunteer, spectator or member of the media. Race week will surely not disappoint. The race towards Boylston Street will continue to showcase some of the world’s best athletes. Fronting the charge on Marathon Monday will be a quartet of defending champions who persevered through some of the harshest weather conditions in race history twelve months ago. Desiree Linden, the determined and resilient American who snapped a 33-year USA winless streak in the women’s open division, returns with hopes of keeping her crown. Linden has said that last year’s race was the culmination of more than a decade of trying to tame the beast of Boston – a race course that rewards those who are both patient and daring. -

A World-Class Cultural & Education Institute

® A World-Class Cultural & Education Institute What an International Marathon Center means for the MetroWest region The 26.2 Foundation's vision is to create a world-class cultural and educational institution that engages visitors intellectually, emotionally and physically. The center will encourage repeat visits through compelling interactive exhibits and best-practice education programs. ® HONOR CELEBRATE INSPIRE With the creation of an International Marathon Center (IMC), the 26.2 Foundation seeks to preserve and promote the importance and contributions of marathoning, advancing the ideals of sportsmanship, competition, fair play and the power of the human spirit. The proposed plans for the IMC call for construction on a multi-acre site on East Main Street (Route 135) in Hopkinton, MA, near the one-mile marker of the Boston Marathon course. Residents of Hopkinton will be asked to approve the lease of the site to the 26.2 Foundation for the Center’s construction. The IMC will offer state-of-the-art facilities and capabilities designed to draw visitors throughout the year. These will include: • Leading-edge conference and meeting facilities • Compelling, interactive exhibitions for multi-purpose use, by both private and public groups “I believe such a facility [as the IMC], encapsulating the special • Research and educational resources history, culture, and valuable research contributions made by the sport • A museum, hall of fame, auditorium, and of running, would be an important marker of Hopkinton’s special place event venue in the sport, and would undoubtedly be an economic benefit to the town • Compelling educational programs linked and its surrounding region.” to state and national fitness, nutrition — Meb Keflezighi, four-time USA Olympian, and civics curricula 2009 New York Marathon Champion, 2014 Boston Marathon Champion www.26-2.org • 26.2 Foundation • P.O. -

1983 Jacksonville River Run 15,000

.- -. .- -.:'t'" 1983 JACKSONVILLE RIVER RUN 15,000 . .. Hosted by: Jacksonville Track Club Sponsored by: Major Sponsor: BARNETT BANK OF JACKSONVILLE Supporting Sponsor: FLORIDA TIMES UNION CONVERSE R.C. COLA OF JACKSONVILLE CITY OF JACKSONVILLE Sports & Entertainment Commissior(' Tourist & Convention Bureau ... In kind Sponsors: SOUTHERN BELL DELMONTE COVER PHOTO: Larry Gwaltney captures the excitement ofth~ sixth annual Jacksonville River Run with this triple exposure photo taken before, during and after the 15K race. The Jacksonville River Run 15K results book is published by World Class Runners Inc. publishers of RUNNER'S UPDATE MAGAZINE. -'~-i":'!-_.... Ra.ce Director: DOUG ALRED Assistant Race Director: EVERETT MORRIS Registration Chairman: JIM COOVERT Awards Designed & Created By: JANE RYAN Layout & Graphics Prepared By: THOMAS KENNY/RUNNER'S UPDATE MAGAZINE RACE NOTES: Tom Kenny RIVER RUN HISTORY A Chronology of the South's Largest 15K DATELINE: JACKSONVILLE, FLORIDA women's division. This time River Run was designated as SPRING, 1977 - Members of the Jacksonville Track the RRCA's National 15K Championships. RU associate Club, after competing in the highly-successful July 4th editor Bob Ludlow, a last-minute entry, was astounded to Peachtree Road Race in Atlanta, decide to stage their own learn, only at the moment he accepted his trophy at the version of this mass-participation race. The Florida Times awards ceremony, that he had captured a national title for Union is quick to realize the potential of the race and offers masters. to sponsor it. By mid-summer, JTC President Gary Hogue 1981-One of the best fields ever assembled set the stage had things well under way. -

The First Thirty Years Central Park Track Club

CENTRAL PARK TRACK CLUB THE FIRST THIRTY YEARS 1972 Dave Blackstone Lynn Blackstone Jack Brennan Fred Burke Cathy Burnam Arnold Fraiman Frank Handelman Marc Howard Fred Lebow Andy Maslow Jerry Miller Richart Miller Kathrine Switzer Robert Urie IN THE BEGINNING, THERE WAS DAVE… “In the early 1970s there were perhaps two dozen runners who trained regularly in Central Park, many of whom did not compete but had track or cross-country backgrounds and stayed in shape, for example, Frank Handelman, Bob Urie, Jack Brennan and myself. Through the late 1960s and early 70s the only team winning Met titles was Millrose, except in cross-country where the NYAC was dominant, fielding national-class runners. I thought it would be fun to organize these regulars into a team, so in September 1972, my wife, Lynn and I called a founding meeting in our apartment and Central Park Track Club was born.” — Dave Blackstone, founder and first president of CPTC That was the genesis of our club. During the The history of CPTC might be divided into two ensuing 30 years, that little band consisting of parts — BG and AG. Long before George Dave and Lynn, Ben Gershmann, Larry Wisniewski came on the scene, CPTC had a Langer, Judge Arnold Fraiman, Walter Nathan, definite presence in local competition. Shelly Bob Urie, Fred Lebow, Frank Handelman, Jack Karlin, Handelman, Brennan, and Blackstone Brennan and a few others, has grown into a were names that frequently showed up as top real presence in New York, with close to four finishers in races. In fact, Dave seems to have hundred members from a variety of ethnic raced so often that in an early Club News piece, backgrounds, of all ages, speeds and resting it was reported he was leaving his job and pulse rates. -

Sports Spotlite Vol. 1 No. 3, July 2020

Tacoma-Pierce County SPORTS SPOTLITE Newsletter of the Shanaman Sports Museum JULY 2020 | Vol.1 No.3 Kaye Hall swimming the backstroke. (Courtesy Kaye Hall) Kaye Hall’s Olympic Triumph By Gail Wood CONTENTS The moment could have been overwhelming, filled with “I can’t.” About Us 2 Lend your Support 2 And yet Kaye Hall, as a 17-year-old youngster Join the Team 5 and a senior at Wilson High School, felt only Our Members 5 excitement, a sense of satisfaction and Hall of Fame Spotlites Mac Wilkins 6 achievement. She was about to begin the Gertrude Wilhelmsen 7 biggest race of her life at the 1968 Olympics. Local Olympians 8 (article continued on page 3) LEND YOUR SUPPORT by Kim Davenport It has been more than a century since our community last faced a pandemic, and the past several months have been a challenge for us all, The mission of the Shanaman Sports Museum of individually and collectively. Tacoma-Pierce County is to recreate the history of sports in the community by chronicling the evolution of various sports through written, visual and audio Like many other organizations in our community, mediums and to educate the public about our sports the Shanaman Sports Museum relies on your heritage. support to fulfill our mission. With the postponement of our annual Tribute to Board of Directors Champions event due to current restrictions on Marc Blau, President public gatherings, we need that support now Colleen Barta, Acting Vice President more than ever. John Wohn, Secretary Terry Ziegler, Treasurer Tom Bona Become a Member Gary Brooks Brad Cheney, Emeritus Membership to the Shanaman Sports Museum Jack Connelly Kyle Crews supports the museum’s efforts to preserve the Steve Finnigan sports history of Tacoma-Pierce County and to Pat Garlock educate the public through online exhibits, Vince Goldsmith including our Online Photo and Artifact catalog, Don GustaFson Kevin Kalal Old-School Sports Programs, Clay Huntington Dave Lawson Broadcast Center, and Tacoma-Pierce County Doug McArthur, Emeritus Sports Hall of Fame. -

Table of Contents

A Column By Len Johnson TABLE OF CONTENTS TOM KELLY................................................................................................5 A RELAY BIG SHOW ..................................................................................8 IS THIS THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES FINEST MOMENT? .................11 HALF A GLASS TO FILL ..........................................................................14 TOMMY A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS ........................................................17 NO LIGHTNING BOLT, JUST A WARM SURPRISE ................................. 20 A BEAUTIFUL SET OF NUMBERS ...........................................................23 CLASSIC DISTANCE CONTESTS FOR GLASGOW ...................................26 RISELEY FINALLY GETS HIS RECORD ...................................................29 TRIALS AND VERDICTS ..........................................................................32 KIRANI JAMES FIRST FOR GRENADA ....................................................35 DEEK STILL WEARS AN INDELIBLE STAMP ..........................................38 MICHAEL, ELOISE DO IT THEIR WAY .................................................... 40 20 SECONDS OF BOLT BEATS 20 MINUTES SUNSHINE ........................43 ROWE EQUAL TO DOUBELL, NOT DOUBELL’S EQUAL ..........................46 MOROCCO BOUND ..................................................................................49 ASBEL KIPROP ........................................................................................52 JENNY SIMPSON .....................................................................................55 -

Norcal Running Review Is Published on a Monthly Basis by the West Valley Track Club

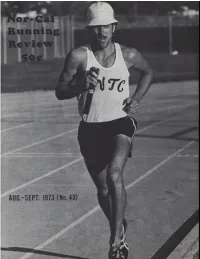

the athletic department RUNNING UNLIMITED JOHN KAVENY ON THE COVER West Valley Track Club's Jim Dare dur ing the final mile (4:35.8), his 30th, in the Runner's World sponsored 24-Hr Relay at San Jose State. Dare's aver age for his 30 miles was 4:47.2, and he led his teammates to a new U.S. Club Record of 284 miles, 224 yards, break ing the old mark, set in 1972 by Tulsa Running Club, by sane nine miles. Full results on pages 17-18. /Wayne Glusker/ STAFF EDITOR: Jack Leydig; PRINTER: Frank Cunningham; PHOTOGRA PHERS: John Marconi, Dave Stock, Wayne Glusker; NOR-CAL PORTRAIT CONTENTS : Jon Hendershott; COACH'S CORNER: John Marconi; WEST VALLEY PORTRAIT: Harold DeMoss; NCRR POINT RACE: Art Dudley; Readers' Poll 3 West Valley Portrait 10 WOMEN: Roxy Andersen, Harmon Brown, Jim Hume, Vince Reel, Dawn This & That 4 Special Articles 10 Bressie; SENIORS: John Hill, Emmett Smith, George Ker, Todd Fer NCRR LDR Point Ratings 5 Scheduling Section 12 guson, David Pain; RACE WALKING: Steve Lund; COLLEGIATE: Jon Club News 6 Race Walking News 14 Hendershott, John Sheehan, Fred Baer; HIGH SCHOOL: Roy Kissin, Classified Ads 8 Track & Field Results 14 Dave Stock, Mike Ruffatto; AAU RESULTS: Jack Leydig, John Bren- Letters to the Editor 8 Road Racing Results 16 nand, Bill Cockerham, Jon Hendershott. --- We always have room for Coach's Comer 9 Late News 23 more help on our staff, especially in the high school and colle NorCal Portrait 9 giate areas, now that cross country season has begun. -

2004 USA Olympic Team Trials: Men's Marathon Media Guide Supplement

2004 U.S. Olympic Team Trials - Men’s Marathon Guide Supplement This publication is intended to be used with “On the Roads” special edition for the U.S. Olympic Team Trials - Men’s Marathon Guide ‘04 Male Qualifier Updates in 2004: Stats for the 2004 Male Qualifiers as of OCCUPATION # January 20, 2004 (98 respondents) Athlete 31 All data is for ‘04 Entrants Except as Noted Teacher/Professor 16 Sales 13 AVERAGE AGE Coach 10 30.3 years for qualifiers, 30.2 for entrants Student 5 (was 27.5 in ‘84, 31.9 in ‘00) Manager 3 Packaging Engineer 1 Business Owner 2 Pediatrician 1 AVERAGE HEIGHT Development Manager 2 Physical Therapist 1 5’'-8.5” Graphics Designer 2 Planner 1 Teacher Aide 2 AVERAGE WEIGHT Researcher 1 U.S. Army 2 140 lbs. Systems Analyst 1 Writer 2 Systems Engineer 1 in 2004: Bartender 1 Technical Analyst 1 SINGLE (60) 61% Cardio Technician 1 Technical Specialist 1 MARRIED (38) 39% Communications Specialist 1 U.S. Navy Officer 1 Out of 98 Consultant 1 Webmaster 1 Customer Service Rep 1 in 2000: Engineer 1 in 2000: SINGLE (58) 51% FedEx Pilot 1 OCCUPATION # MARRIED (55) 49% Film 1 Teacher/Professor 16 Out of 113 Gardener 1 Athlete 14 GIS Tech 1 Coach 11 TOP STATES (MEN ONLY) Guidance Counselor 1 Student 8 (see “On the Roads” for complete list) Horse Groomer 1 Sales 4 1. California 15 International Ship Broker 1 Accountant 4 2. Michigan 12 Mechanical Engineer 1 3. Colorado 10 4. Oregon 6 Virginia 6 Contents: U.S. -

LE STATISTICHE DELLA MARATONA 1. Migliori Prestazioni Mondiali Maschili Sulla Maratona Tabella 1 2. Migliori Prestazioni Mondial

LE STATISTICHE DELLA MARATONA 1. Migliori prestazioni mondiali maschili sulla maratona TEMPO ATLETA NAZIONALITÀ LUOGO DATA 1) 2h03’38” Patrick Makau Musyoki KEN Berlino 25.09.2011 2) 2h03’42” Wilson Kipsang Kiprotich KEN Francoforte 30.10.2011 3) 2h03’59” Haile Gebrselassie ETH Berlino 28.09.2008 4) 2h04’15” Geoffrey Mutai KEN Berlino 30.09.2012 5) 2h04’16” Dennis Kimetto KEN Berlino 30.09.2012 6) 2h04’23” Ayele Abshero ETH Dubai 27.01.2012 7) 2h04’27” Duncan Kibet KEN Rotterdam 05.04.2009 7) 2h04’27” James Kwambai KEN Rotterdam 05.04.2009 8) 2h04’40” Emmanuel Mutai KEN Londra 17.04.2011 9) 2h04’44” Wilson Kipsang KEN Londra 22.04.2012 10) 2h04’48” Yemane Adhane ETH Rotterdam 15.04.2012 Tabella 1 2. Migliori prestazioni mondiali femminili sulla maratona TEMPO ATLETA NAZIONALITÀ LUOGO DATA 1) 2h15’25” Paula Radcliffe GBR Londra 13.04.2003 2) 2h18’20” Liliya Shobukhova RUS Chicago 09.10.2011 3) 2h18’37” Mary Keitany KEN Londra 22.04.2012 4) 2h18’47” Catherine Ndereba KEN Chicago 07.10.2001 1) 2h18’58” Tiki Gelana ETH Rotterdam 15.04.2012 6) 2h19’12” Mizuki Noguchi JAP Berlino 15.09.2005 7) 2h19’19” Irina Mikitenko GER Berlino 28.09.2008 8) 2h19’36’’ Deena Kastor USA Londra 23.04.2006 9) 2h19’39’’ Sun Yingjie CHN Pechino 19.10.2003 10) 2h19’50” Edna Kiplagat KEN Londra 22.04.2012 Tabella 2 3. Evoluzione della migliore prestazione mondiale maschile sulla maratona TEMPO ATLETA NAZIONALITÀ LUOGO DATA 2h55’18”4 Johnny Hayes USA Londra 24.07.1908 2h52’45”4 Robert Fowler USA Yonkers 01.01.1909 2h46’52”6 James Clark USA New York 12.02.1909 2h46’04”6