About Which No One Wants to Read?)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The News Flow and Copy Editing

Ganesh Kumar Ranjan Faculty, MJMC, MMHAPU,Patna The news flow and copy editing INTRODUCTION In media organizations, news stories flow through a channel from the reporter or a writer to the editor. The reporter who does the leg-work or a writer who contributes a piece of writing acts as the first gate-keeper. The manuscript Reporters or writers file is called copy. In the process, the copy passes through many media gate-keepers who make inputs so that the copy will conform to the organisational houses style, news value, ethics and legal standards. In doing that, both the reporter and others in the copy flow chain are guided by so many factors which could be personal, socio-economic, political and religious factors. The News Flow In newspapers and magazines, there are so many intermediary communicators between an event and the ultimate receiver (the readers). A magazine’s schedule allocates time for all the editorial tasks, from initial commissioning of news story to reporters, through picture research to sub- editing and layout. The nature of the information will determine the nature and number of the intermediaries. These intermediaries are the gate-keepers. For instance, a copy can flow from the reporter to the deputy political editor, to the political editor, deputy editor and then the editor. The sub editors have to enforce that schedule, ensuring that copy arrives and pages leave on time. The subs should have editors support in their struggle to enforce deadlines. They are also responsible for keeping control of copy-flow. Ensuring that the correct files come in and go out. -

Copy Editing and Proofreading Symbols

Copy Editing and Proofreading Symbols Symbol Meaning Example Delete Remove the end fitting. Close up The tolerances are with in the range. Delete and Close up Deltete and close up the gap. not Insert The box is inserted correctly. # # Space Theprocedure is incorrect. Transpose Remove the fitting end. / or lc Lower case The Engineer and manager agreed. Capitalize A representative of nasa was present. Capitalize first letter and GARRETT PRODUCTS are great. lower case remainder stet stet Let stand Remove the battery cables. ¶ New paragraph The box is full. The meeting will be on Thursday. no ¶ Remove paragraph break The meeting will be on Thursday. no All members must attend. Move to a new position All members attended who were new. Move left Remove the faulty part. Flush left Move left. Flush right Move right. Move right Remove the faulty part. Center Table 4-1 Raise 162 Lower 162 Superscript 162 Subscript 162 . Period Rewrite the procedure. Then complete the tasks. ‘ ‘ Apostrophe or single quote The companys policies were rewritten. ; Semicolon He left however, he returned later. ; Symbol Meaning Example Colon There were three items nuts, bolts, and screws. : : , Comma Apply pressure to the first second and third bolts. , , -| Hyphen A valuable byproduct was created. sp Spell out The info was incorrect. sp Abbreviate The part was twelve feet long. || or = Align Personnel Facilities Equipment __________ Underscore The part was listed under Electrical. Run in with previous line He rewrote the pages and went home. Em dash It was the beginning so I thought. En dash The value is 120 408. -

Editorial Literacy:Reconsidering Literary Editing As Critical Engagement in Writing Support

St. John's University St. John's Scholar Theses and Dissertations 2020 Editorial Literacy:Reconsidering Literary Editing as Critical Engagement in Writing Support Anna Cairney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.stjohns.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Creative Writing Commons EDITORIAL LITERACY: RECONSIDERING LITERARY EDITING AS CRITICAL ENGAGEMENT IN WRITING SUPPORT A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY to the faculty in the department of ENGLISH of ST. JOHN’S COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES at ST. JOHN’S UNIVERSITY New York by Anna Cairney Date Submitted: 1/27/2020 Date Approved: 1/27/2020 __________________________________ __________________________________ Anna Cairney Derek Owens, D.A. © Copyright by Anna Cairney 2020 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT EDITORIAL LITERACY: RECONSIDERING LITERARY EDITING AS CRITICAL ENGAGEMENT IN WRITING SUPPORT Anna Cairney Editing is usually perceived in the pejorative within in the literature of composition studies generally, and specifically in writing center studies. Regardless if the Writing Center serves mostly undergraduates or graduates, the word “edit” has largely evolved to a narrow definition of copyediting or textual cleanup done by the author at the end of the writing process. Inversely, in trade publishing, editors and agents work with writers at multiple stages of production, providing editorial feedback in the form of reader’s reports and letters. Editing is a rich, intellectual skill of critically engaging with another’s text. What are the implications of differing literacies of editing for two fields dedicated to writing production? This dissertation examines the editorial practices of three leading 20th century editors: Maxwell Perkins, Katharine White, and Ursula Nordstrom. -

Copy Editing 19-20 Web

COPY EDITING BRADLEY WILSON, PH.D. CONTEST DIRECTOR | 2020 PHOTO BY BRADLEY WILSON copy editor Seldom a formal title. Also: copy editing, copy edit. WHY STUDY COPY EDITING? Marketable skills • attention to detail • teamwork • ability to meet deadlines • time management • problem solving • cultural awareness WHAT IT’S NOT • a headline writing contest • a current events contest • a spelling contest WHAT IT IS a contest that focuses on editing, including • knowledge of current events • grammar, spelling, punctuation, style • sentence structure, including passive voice and word choice • media law and ethics HIGH-LEVEL EDITING • Are there any legal issues (libel)? • Did the reporter interview the right people? • Did the reporter interview enough people? • Did the reporter ask the right questions? • Does the story cover all sides? • Is the story in context? CULTURAL LITERACY MID-LEVEL EDITING • Does the story flow well? Has the reporter made good use of transitions? • Are sentences structured correctly? • Has writer made appropriate use of passive voice? • Is vocabulary appropriate for the audience? • Is math correct? • Is geography correct? CULTURAL SENSITIVITY • Avoiding sexist writing • Being insensitive • Cultural awareness mentally disabled, intellectually disabled, developmentally disabled The preferred terms, not mentally retarded. disabled, handicapped In general, do not describe an individual as disabled or handicapped unless it is clearly pertinent to a story. If a description must be used, try to be specific. firefighter, fireman The preferred term to describe a person who fights fire is firefighter. mailman Mail or letter carrier is preferable. transsexual Use transgender to describe individuals who have acquired the physical characteristics of the opposite sex or present themselves in a way that does not correspond with their sex at birth. -

Editorial Resources List NEO STC Panel Discussion: Editing Tools, Resources, and Processes Prepared by Sarah Burke March 14, 2013

Editorial Resources List NEO STC Panel Discussion: Editing Tools, Resources, and Processes Prepared by Sarah Burke March 14, 2013 Reading Books STC Technical Editing SIG Virtual Bookshelf Copyediting Erin Brenner’s Resources for Editors Cite Right Charles Lipson The Copyeditor’s Handbook, 2nd ed. Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace, 10th ed. Joseph M. Williams and Gregory G. Colomb The Subversive Copy Editor Carol Fisher Saller Industry Publications Copyediting Newsletter A top-notch newsletter, founded in 1990, that explores the usage and evolution of the English language with a focus on the concerns of copyeditors. Corrigo Newsletter Online newsletter of the STC Technical Editing SIG published quarterly. Articles cover a wide variety of current and applied technical editing topics. Style Guides Note: Many, but not all, of these style guides are online, and many require paid subscriptions. Academic/Book Publishing The Chicago Manual of Style Online One of the “go-to” style guides for determining style conventions (and even settling debates). Business Writing The Gregg Reference Manual Online Comprehensive guide to business writing with simple explanations and plentiful examples. Government Writing The Government Printing Office Style Manual, 2008 ed. Style guide of the US Government Printing Office that contains federal government printing standards. Medical Writing AMA Manual of Style Online The industry-standard style guide for anyone involved in medical and scientific publishing. NEO STC Panel Discussion | Editorial Resources List 1 Newspaper/Magazine Writing Associated Press Stylebook The style guide for journalists, the media, and those publishing in less technical fields (including B2B trade publications). Science Writing Scientific Style and Format: The CSE Manual for Authors, Editors, and Publishers, 7th ed. -

Butcher's Copy-Editing

BUTCHER’S COPY-EDITING Judith Butcher, Caroline Drake and Maureen Leach BUTCHER’S COPY-EDITING The Cambridge Handbook for Editors, Copy-editors and Proofreaders Fourth edition, fully revised and updated cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521847131 © Cambridge University Press 1975, 1981, 1992, 2006 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published in print format 2006 isbn-13 978-0-511-25039-2 eBook (NetLibrary) isbn-10 0-511-25039-8 eBook (NetLibrary) isbn-13 978-0-521-84713-1 hardback isbn-10 0-521-84713-3 hardback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of urls for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Contents List of illustrations viii 4 Illustrations 69 Preface to the fourth edition ix 4.1 What needs to be done 75 Preface to the third edition x 4.2 Line illustrations 80 Preface to the second edition xii 4.3 Maps 85 Preface to the first edition xii 4.4 Graphs 88 Acknowledgements -

Editing for Today's Changing Media

PART 1 Editing in the Age of Convergence C HAPTER 1 Editing for Today’s Changing Media THE EDItor’s Changing ROLE For generations, news was produced and distributed in assembly-line fashion. Reporters gathered and wrote it, editors edited it, and publishers produced and dis- tributed it in print or broadcast form to mass audiences. It was a one-to-many model born in the Industrial Revolution. Editors in that environment served as gatekeepers. They decided when to open the gate, allowing information to flow to the public. Editors had total control over what was published or broadcast. They determined which stories were newsworthy— those they deemed useful, relevant or interesting to their audiences. Editors controlled the gate, and consumers got only what editors gave them. Editors also controlled the play a story received. Was it newsworthy enough for Page One, where almost everyone would notice it, or should it be relegated to a brief on Page 37, where few would read it? Did it make the cover of Time, or did it not make the magazine at all? Did it warrant top billing on the evening newscast, or was it left to the local newspaper? Editors were powerful. They called all the shots. Today, that is far from universally true. The Internet and wireless devices (mobile phones and tablet computers) allow users to choose what news they want to consume from multiple providers—some traditional and some not—and from digital databases of information vastly larger than the content of the nation’s largest newspaper or a 24-hour-a-day cable-television news channel. -

Editing Designed.Pmd

DIPLOMA IN JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION DJMC-3 Editing Block 1 Editing Unit-1 Editing: concept, process and significance Unit-2 Editorial Values: objectivity, facts, impartiality and balance Unit-3 Concept of news and news making Unit-4 Difference between newspaper/ radio and TV news editing Unit-5 Challenges before editor: bias, slants and pressures 1 Expert Committee Members Dr. Mrinal Chatterjee (Chairman) Professor, IIMC, Dhenkanal Abhaya Padhi Former, ADG, Prasar Bharati Dr. Prdeep Mohapatra Former HOD, JMC, Berhampur University Sushant Kumar Mohanty Editor, The Samaja(Special Invitee) Dr. Dipak Samantarai Director, NABM, BBSR Dr. Asish Kumar Dwivedy Asst. Professor, Humanities and Social Science (Communication Studies), SoA University, BBSR Sujit Kumar Mohanty Asst. Professor, JMC, Central University of Orissa, Koraput Ardhendu Das Editor, News 7 Patanjali Kar Sharma State Correspondent, News 24X7 Jyoti Prakash Mohapatra (Member Convenor) Academic Consultant, Odisha State Open University Course Writer: Sourav Gupta Edited By: Dr. Mrinal Chatterjee, Professor, Indian Institute of Mass Communication, Dhenkanal 2 DJMC-3 Block 1 Content Unit-1 Editing: concept, process and significance 1.0 Unit Structure 5 1.1 Learning Objectives 5 1.2 Introduction 5 1.3 Concept of Editing 6 1.4 Relationship between Editing and Editors 6 1.5 Process of News Editing 7 1.6 Editing and its Need 8 1.7 Rules of Editing 9 1.8 Copy Editing 11 1.9 Editorial and Editorial Boards 11 1.10 Types of Editor 11 1.11 Significance of Editing 14 1.12 Check Your Progress -

Digital Sub-Editing and Design (Focal Journalism)

Digital Sub-editing and Design Dedication For my wife Deirdre, with love and admiration. Journalism Subject Adviser to Focal Press: Professor John Herbert Digital Sub-editing and Design Stephen Quinn Focal Press OXFORD AUCKLAND BOSTON JOHANNESBURG MELBOURNE NEW DELHI Focal Press An imprint of Butterworth-Heinemann Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 225 Wildwood Avenue, Woburn, MA 01801-2041 A division of Reed Educational and Professional Publishing Ltd First published 2001 © Stephen Quinn 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1P 0LP. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publishers British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 0 240 51639 7 Designer: Stephen Quinn Printed and bound in Great Britain Contents Acknowledgements vii Introduction 1 SECTION A: ELECTRONIC EDITING Chapter 1: The editor’s changing yet consistent role 9 How the digital environment is changing the job. New roles in an information-clogged world. -

¶ What Copyeditors Do

CHAPTER 1 ¶ What Copyeditors Do Copyeditors always serve the needs of three constituencies: the author(s)—the person (or people) who wrote or compiled the manuscript the publisher—the individual or company that is paying the cost of producing and distributing the material the readers—the people for whom the material is being produced All these parties share one basic desire: an error-free publication. To that end, the copy- editor acts as the author’s second pair of eyes, pointing out—and usually correcting— mechanical errors and inconsistencies; errors or infelicities of grammar, usage, and syntax; and errors or inconsistencies in content. If you like alliterative mnemonic devices, you can conceive of a copyeditor’s chief concerns as comprising the “4 Cs”—clarity, coherency, consistency, and correctness—in service of the “Cardinal C”: communication. Certain projects require the copyeditor to serve as more than a second set of eyes. Heavier intervention may be needed, for example, when the author does not have native or near-native fluency in English, when the author is a professional or a techni- cal expert writing for a lay audience, when the author is addressing a readership with limited English proficiency, or when the author has not been careful in preparing the manuscript. Sometimes, too, copyeditors find themselves juggling the conflicting needs and desires of their constituencies. For example, the author may feel that the manuscript requires no more than a quick read-through to correct a handful of typographical errors, while the publisher, believing that a firmer hand would benefit the final product, instructs the copyeditor to prune verbose passages. -

Editing Syllabus Spring 2014 FINAL

University of Iowa College of Liberal Arts and Sciences School of Journalism and Mass Communication Spring 2014 - 19:136:SCA Editing the News 4 semester hours Tuesdays and Thursdays – 4:30-6:20 p.m. W340 Adler Journalism Bldg. Course policies are governed by the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. CLAS policies are included in this syllabus. Instructor: Vanessa Shelton, Ph.D., adjunct assistant professor Office: E346 Adler Journalism Bldg. Phone: 335-3321 Email: [email protected] Office hours: 2-4 p.m. Tuesdays and Thursdays, or by appointment Course Description, Objectives and Goals: Editors perform a variety of important roles within news media organizations. This course will explore those roles while also focusing on critical editorial skills and responsibilities across media platforms. Editors are responsible for the final news product, and often work as part of a team to this end. They coach staff and critique their performance prior to and after production, and are involved in such matters as the visual presentation of content and assuring it is accurate. Editors also attend to news planning, gathering and work routines, and to the adherence to legal and ethical standards of the industry. In addition, they also may serve as a liaison with the public. With traditional and contemporary editorial roles in mind, this course will help students to sharpen their journalistic skills, while being critical and creative thinkers as they engage in the editing process. Because the news is fluid, editors and by extension students in this class, must be capable of adapting to change and making informed decisions within the realm of solid journalistic standards. -

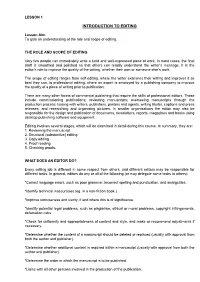

Introduction to Editing

LESSON 1 INTRODUCTION TO EDITING Lesson Aim To gain an understanding of the role and scope of editing. THE ROLE AND SCOPE OF EDITING Very few people can immediately write a lucid and well-expressed piece of work. In most cases, the final draft is smoothed and polished so that others can readily understand the writer’s message. It is the editor’s role to improve the quality of the writing, whether their own or someone else’s work. The scope of editing ranges from self editing, where the writer examines their writing and improves it as best they can, to professional editing, where an expert is employed by a publishing company to improve the quality of a piece of writing prior to publication. There are many other facets of commercial publishing that require the skills of professional editors. These include commissioning publications; reviewing manuscripts; overseeing manuscripts through the production process; liaising with writers, publishers, printers and agents; writing blurbs, captions and press releases; and researching and organising pictures. In smaller organisations the editor may also be responsible for the design and publication of documents, newsletters, reports, magazines and books using desktop publishing software and equipment. Editing involves several stages, which will be examined in detail during this course. In summary, they are: 1. Reviewing the manuscript 2. Structural (substantive) editing 3. Copy editing 4. Proof reading 5. Checking proofs. WHAT DOES AN EDITOR DO? Every editing job is different in some respect from others, and different editors may be responsible for different tasks. In general, editors do any or all of the following (or may delegate some tasks to others): *Correct language errors, such as poor grammar, incorrect spelling and punctuation, and ambiguities.