Student: Kevin Mulder Date

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Nightmare, Or the Revelation of the Uncanny in Three

The American Nightmare, or the Revelation of the Uncanny in three documentary films by Werner Herzog La pesadilla americana, o la revelación de lo extraño en tres documentales de DIEGO ZAVALA SCHERER1 Werner Herzog http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7362-4709 This paper analyzes three Werner Herzog’s films: How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck (1976), Huie’s Sermon (1981) and God´s Angry Man (1981) through his use of the sequence shot as a documentary device. Despite the strong relation of this way of shooting with direct cinema, Herzog deconstructs its use to generate moments of filmic revelation, away from a mere recording of events. KEYWORDS:Documentary device, sequence shot, Werner Herzog, direct cinema, ecstasy. El presente artículo analiza tres obras de la filmografía de Werner Herzog: How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck (1976), Huie´s Sermon (1981) y God´s Angry Man (1981), a partir del uso del plano secuencia como dispositivo documental. A pesar del vínculo de esta forma de puesta en cámara con el cine directo, Herzog deconstruye su uso para la generación de momentos de revelación fílmica, lejos del simple registro. PALABRAS CLAVE: Dispositivo documental, plano secuencia, Werner Herzog, cine directo, éxtasis. 1 Tecnológico de Monterrey, México. E-mail: [email protected] Submitted: 01/09/17. Accepted: 14/11/17. Published: 12/11/18. Comunicación y Sociedad, 32, may-august, 2018, pp. 63-83. 63 64 Diego Zavala Scherer INTRODUCTION Werner Herzog’s creative universe, which includes films, operas, poetry books, journals; is labyrinthine, self-referential, iterative … it is, we might say– in the words of Deleuze and Guattari (1990) when referring to Kafka’s work – a lair. -

An Anguished Self-Subjection: Man and Animal in Werner Herzog's Grizzly

An Anguished Self-Subjection: Man and Animal in Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man Stefan Mattessich Santa Monica College Do we not see around and among us men and peoples who no longer have any essence or identity—who are delivered over, so to speak, to their inessentiality and their inactivity—and who grope everywhere, and at the cost of gross falsifications, for an inheritance and a task, an inheritance as task? Giorgio Agamben The Open erner herzog’s interest in animals goes hand in hand with his Winterest in a Western civilizational project that entails crossing and dis- placing borders on every level, from the most geographic to the most corporeal and psychological. Some animals are merely present in a scene; early in Fitzcarraldo, for instance, its eponymous hero—a European in early-twentieth-century Peru—plays on a gramophone a recording of his beloved Enrico Caruso for an audience that includes a pig. Others insist in his films as metaphors: the monkeys on the raft as the frenetic materializa- tion of the conquistador Aguirre’s final insanity. Still others merge with characters: subtly in the German immigrant Stroszek, who kills himself on a Wisconsin ski lift because he cannot bear to be treated like an animal anymore or, literally in the case of the vampire Nosferatu, a kindred spirit ESC 39.1 (March 2013): 51–70 to bats and wolves. But, in every film, Herzog is centrally concerned with what Agamben calls the “anthropological machine” running at the heart of that civilizational project, which functions to decide on the difference between man and animal. -

L'invention Musicale Face À La Nature Dans Grizzly

L’invention musicale face à la nature dans Grizzly Man, The Wild Blue Yonder et La grotte des rêves perdus de Werner Herzog Vincent Deville To cite this version: Vincent Deville. L’invention musicale face à la nature dans Grizzly Man, The Wild Blue Yonder et La grotte des rêves perdus de Werner Herzog. Revue musicale OICRM, Observatoire interdisciplinaire de création et de recherche en musique, 2018, 5 (n°1), s.p. hal-02133197v1 HAL Id: hal-02133197 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02133197v1 Submitted on 17 May 2019 (v1), last revised 15 Jul 2019 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License L’invention musicale face à la nature dans Grizzly Man, The Wild Blue Yonder et La grotte des rêves perdus de Werner Herzog Vincent Deville Résumé Quand le cinéaste allemand Werner Herzog réalise ou produit trois documentaires sur la création et l’enregistrement de la musique de trois de ses films entre 2005 et 2011, il effectue un double geste de révélation et d’incarnation : les notes nous deviennent visibles à travers le corps des musiciens. -

Mediated Meetings in Grizzly Man

An Argument across Time and Space: Mediated Meetings in Grizzly Man TRENT GRIFFITHS, Deakin University, Melbourne ABSTRACT In Werner Herzog’s 2005 documentary Grizzly Man, charting the life and tragic death of grizzly bear protectionist Timothy Treadwell, the medium of documentary film becomes a place for the metaphysical meeting of two filmmakers otherwise separated by time and space. The film is structured as a kind of ‘argument’ between Herzog and Treadwell, reimagining the temporal divide of past and present through the technologies of documentary filmmaking. Herzog’s use of Treadwell’s archive of video footage highlights the complex status of the filmic trace in documentary film, and the possibilities of documentary traces to create distinct affective experiences of time. This paper focuses on how Treadwell is simultaneously present and absent in Grizzly Man, and how Herzog’s decision to structure the film as a ‘virtual argument’ with Treadwell also turns the film into a self-reflexive project in which Herzog reconsiders and re-presents his own image as a filmmaker. With reference to Herzog’s notion of the ‘ecstatic truth’ lying beneath the surface of what the documentary camera records, this article also considers the ethical implications of Herzog’s use of Treadwell’s archive material to both tell Treadwell’s story and work through his own authorial identity. KEYWORDS Documentary time, self-representation, digital film, trace, authorship, Werner Herzog. Introduction The opening scene of Grizzly Man (2005), Werner Herzog’s documentary about the life and tragic death of grizzly bear protectionist and amateur filmmaker Timothy Treadwell, shows Treadwell filming himself in front of bears grazing in a pasture, addressing the camera as though a wildlife documentary presenter. -

Documentary Movies

Libraries DOCUMENTARY MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America DVD-2043 56 Up DVD-8322 180 DVD-3999 60's DVD-0410 1-800-India: Importing a White-Collar Economy DVD-3263 7 Up/7 Plus Seven DVD-1056 1930s (Discs 1-3) DVD-5348 Discs 1 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green DVD-8778 1930s (Discs 4-5) DVD-5348 Discs 4 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green c.2 DVD-8778 c.2 1964 DVD-7724 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 1968 with Tom Brokaw DVD-5235 9500 Liberty DVD-8572 1983 Riegelman's Closing/2008 Update DVD-7715 Abandoned: The Betrayal of America's Immigrants DVD-5835 20 Years Old in the Middle East DVD-6111 Abolitionists DVD-7362 DVD-4941 Aboriginal Architecture: Living Architecture DVD-3261 21 Up DVD-1061 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House Divided DVD-0001 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 Absent from the Academy DVD-8351 24 City DVD-9072 Absolutely Positive DVD-8796 24 Hours 24 Million Meals: Feeding New York DVD-8157 Absolutely Positive c.2 DVD-8796 c.2 28 Up DVD-1066 Accidental Hero: Room 408 DVD-5980 3 Times Divorced DVD-5100 Act of Killing DVD-4434 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Addicted to Plastic DVD-8168 35 Up DVD-1072 Addiction DVD-2884 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 Address DVD-8002 42 Up DVD-1079 Adonis Factor DVD-2607 49 Up DVD-1913 Adventure of English DVD-5957 500 Nations DVD-0778 Advertising and the End of the World DVD-1460 -

'Antiphusis: Werner Herzog's Grizzly Man'

Film-Philosophy, 11.3 November 2007 Antiphusis: Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man Benjamin Noys University of Chichester The moon is dull. Mother Nature doesn’t call, doesn’t speak to you, although a glacier eventually farts. And don’t you listen to the Song of Life. Werner Herzog1 At the heart of the cinema of Werner Herzog lies the vision of discordant and chaotic nature – the vision of anti-nature. Throughout his work we can trace a constant fascination with the violence of nature and its indifference, or even hostility, to human desires and ambitions. For example, in his early film Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970) we have the recurrent image of a crippled chicken continually pecked by its companions.2 Here the violence of nature provides a sly prelude to the anarchic carnival violence of the dwarfs’ revolt against their oppressive institution. This fascination is particularly evident in his documentary filmmaking, although Herzog himself deconstructs this generic category. In the ‘Minnesota Declaration’ (1999)3 on ‘truth and fact in documentary cinema’ he radically distinguishes between ‘fact’, linked to norms and the limits of Cinéma Vérité, and ‘truth’ as ecstatic illumination, which ‘can be reached only through fabrication and imagination and stylization’ (in Cronin (ed.) 2002, 301). In particular he identifies nature as the site of this ecstatic illumination – in which we find ‘Lessons of Darkness’ – but only through the lack of any ‘voice’ of nature. While Herzog constantly films nature he films it as hell or as utterly alien. This is not a nature simply corrupted by humanity but a nature inherently ‘corrupt’ in 1 In Cronin (ed.) 2002, 301. -

Conceiving Grizzly Man Through the "Powers of the False" Eric Dewberry, Georgia State University, US

Conceiving Grizzly Man through the "Powers of the False" Eric Dewberry, Georgia State University, US Directed by New German Cinema pioneer Werner Herzog, Grizzly Man (2005) traces the tragic adventures of Timothy Treadwell, self-proclaimed ecologist and educator who spent thirteen summers living among wild brown bears in the Katmai National Park, unarmed except for a photographic and video camera. In 2003, Treadwell and his girlfriend, Amy Huguenard, were mauled to death and devoured by a wild brown bear. The event is captured on audiotape, and their remains were found in the area around their tent and inside Bear #141, who was later killed by park officials. Herzog's documentary is assembled through interviews of friends close to Treadwell, various professionals, family, and more than 100 hours of footage that Treadwell himself captured in his last five years in Alaska. Grizzly Man is more than a conventional wildlife documentary, as the title of the film emphasizes the centrality of the main protagonist to the story. Herzog subjectively structures the film to take the viewer on a dialectical quest between his and Treadwell's visions about man versus nature and life versus death. As Thomas Elsaesser recognized early in Herzog's career, the filmmaker is famous for reveling in the lives of eccentric characters, who can be broken down into two different subjects: "overreachers," like the prospecting rubber baron Fitzcarraldo and the maniacal conquistador Aguirre, or "underdogs" like Woyzeck, all of them played by the equally unconventional German actor Klaus Kinski (Elsaesser, 1989). Including Herzog's documentary subjects, they are all outsiders, living on the edge, and in excessive pursuit of their goals in violation of what is considered normal and ordinary in society. -

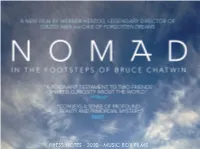

Bruce Chatwin, a Kindred Spirit Who Dedicated His Life to Illuminating the Mysteries of the World

PRESS NOTES - 2020 - MUSIC BOX FILMS LOGLINE Werner Herzog travels the globe to reveal a deeply personal portrait of his friendship with the late travel writer Bruce Chatwin, a kindred spirit who dedicated his life to illuminating the mysteries of the world. SYNOPSIS Werner Herzog turns the camera on himself and his decades-long friendship with the late travel writer Bruce Chatwin, a kindred spirit whose quest for ecstatic truth carried him to all corners of the globe. Herzog’s deeply personal portrait of Chatwin, illustrated with archival discoveries, film clips, and a mound of “brontosaurus skin,” encompasses their shared interest in aboriginal cultures, ancient rituals, and the mysteries stitching together life on earth. WERNER HERZOG Werner Herzog was born in Munich on September 5, 1942. He grew up in a remote mountain village in Bavaria and studied History and German Literature in Munich and Pittsburgh. He made his first film in 1961 at the age of 19. Since then he has produced, written, and directed more than sixty feature- and documentary films, such as Aguirre der Zorn Gottes (AGUIRRE, THE WRATH OF GOD, 1972), Nosferatu Phantom der Nacht (NOSFERATU, 1978), FITZCARRALDO (1982), Lektionen in Finsternis (LESSONS OF DARKNESS, 1992), LITTLE DIETER NEEDS TO FLY (1997), Mein liebster Feind (MY BEST FIEND, 1999), INVINCIBLE (2000), GRIZZLY MAN (2005), ENCOUNTERS AT THE END OF THE WORLD (2007), Die Höhle der vergessenen Träume (CAVE OF FORGOTTEN DREAMS, 2010). Werner Herzog has published more than a dozen books of prose, and directed as many operas. Werner Herzog lives in Munich and Los Angeles. -

Grizzly Man Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmforum.com Grizzly Man Discussion Guide Director: Werner Herzog Year: 2005 Time: 103 min You might know this director from: Encounters At the End of the World (2007) Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010) My Best Fiend (1999) Happy People: A Year in the Taiga (2010) Fitcarraldo (1982) Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) FILM SUMMARY GRIZZLY MAN is the story of a bear enthusiast named Timothy Treadwell. With camera in hand, he spent 13 summers in Katmai National Park and Preserve among wild grizzly bears before he was killed in 2003 by one of the bears he had protected on several occasions. Amie Huguenard, his girlfriend, was with him at the time and was also killed. Treadwell had gained a lot of media attention, frequently appearing in schools and on TV shows like the Late Night Show with David Letterman. After Treadwell’s death, prolific film director Werner Herzog took interest Treadwell’s story and began to put the pieces together. Through Treadwell’s own film footage and interviews with people who knew him best, we get to know a man who struggled with his past and claimed to find his calling amongst Alaska’s wildest bears. As Treadwell immerses himself in their daily lives, the bears accepted his presence, followed him, slept near his tent and permited him to enter their space. He gave them names and sang to them. Though Treadwell was known for being a brave, passionate man, Herzog found him to be a disturbed individual who had a skewed perspective of nature and carried a death wish till the end of his life. -

Documentary Films Audiences in Europe Findings from the Moving Docs Survey

1 Credit: Moving Docs DOCUMENTARY FILMS AUDIENCES IN EUROPE FINDINGS FROM THE MOVING DOCS SURVEY HUW D JONES July 2020 2 CONTENTS Project team .............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Foreword ................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Key findings ............................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Study method ............................................................................................................................................................................ 9 1. Who watches documentaries? ........................................................................................................................................ 11 2. Where are documentaries viewed? ............................................................................................................................... -

Sarkar-And-Wolf-Documentary-Acts-Interview-With-Madhusree-Dutta.Pdf

LeadershipRoundtable Insights from Jaina text Saman Suttam 21 BioScope Documentary Acts: 3(1) 21–34 © 2012 Screen South Asia Trust An Interview with SAGE Publications Los Angeles, London, Madhusree Dutta New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC DOI: 10.1177/097492761100300103 http://bioscope.sagepub.com Bhaskar Sarkar Nicole Wolf Keywords Documentary form and language, citizenship, realism, melodrama and performance, authorship and collaboration, the political The following interview is based on a series of conversations we have had with Madhusree Dutta over the past few years. We condensed the breadth and depth of these stimulating exchanges into five ques- tions which we posed to her via email. The text below is thus both a way of reflecting upon as well as a starting point for further engagements with Dutta’s practice and thinking. Bhaskar Sarkar and Nicole Wolf The trajectory of your work, from your first documentary film I Live in Behrampada (1993), via films such as Memories of Fear (1995) or Scribbles on Akka (2000) to your current curatorial practice for the ongoing large scale research and archival project Cinema City, which developed out of 7 Islands and a Metro (2007), shows a constant search for creative practices and formal languages to respond to your current social and political terrain and the questions of urgency this calls forth. Your relation to the Indian women’s movement and your negotiation with the issues and theoretical concerns coming from feminist thought appear to play a significant role here. This relation was even institutionalized via your co- founding of Majlis in 1990, with the feminist lawyer Flavia Agnes, which brought you close to the realm of rights and maybe even law. -

A Collection of Essays on Werner Herzog

Encounters at the End of the World: A Collection of Essays on Werner Herzog Author: Michael Mulhall Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/542 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2008 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Encounters at the End of the World: A Collection of Essays on Werner Herzog “I am my films” Michael Mulhall May 1, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 5. Chapter 1: Herzog’s Cultural Framework: Real and Perceived 21. Chapter 2: Herzog the Auteur 35. Chapter 3: Herzog/Kinski 48. Chapter 4: Blurring the Line 59. Works Cited Werner Herzog is one of the most well-known European art-house directors alive today (Cronin viii). Born in 1944 in war-torn Munich, Herzog has been an outsider from the start. He shot his first film, an experimental short, with a stolen camera. He has infuriated and confounded countless actors, producers, crew-members and studios in his lengthy career with his insistence on doing things his own way. Due to this maverick persona and the specific “adventurous madman” mystique he has cultivated over the past forty years, Herzog has attracted a large following worldwide. Herzog is perhaps best known for the lush but unforgiving jungles of Aguirre: Der Zorn Gottes (1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982) and his contemplative musings on the structures of society in The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974) and Stroszek (1977). Though he has never been a huge commercial success in terms of theater receipts, he has had a relatively impressive recent run at the box office, including the much-heralded Grizzly Man (2005) and his long awaited return to feature filmmaking, Rescue Dawn (2006).