Vineyard Establishment for the Connecticut Homeowner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

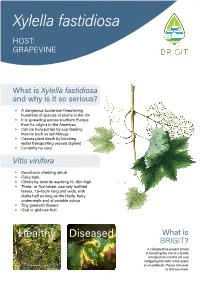

Xylella Fastidiosa HOST: GRAPEVINE

Xylella fastidiosa HOST: GRAPEVINE What is Xylella fastidiosa and why is it so serious? ◆ A dangerous bacterium threatening hundreds of species of plants in the UK ◆ It is spreading across southern Europe from its origins in the Americas ◆ Can be transported by sap-feeding insects such as spittlebugs ◆ Causes plant death by blocking water transporting vessels (xylem) ◆ Currently no cure Vitis vinifera ◆ Deciduous climbing shrub ◆ Flaky bark ◆ Climbs by tendrils reaching 15–18m high ◆ Three- or five-lobed, coarsely toothed leaves, 7.5–15cm long and wide, with stalks half as long as the blade, hairy underneath and of variable colour ◆ Tiny greenish flowers ◆ Oval or globose fruit Healthy Diseased What is BRIGIT? A collaborative project aimed at reducing the risk of a Xylella introduction into the UK and mitigating the risks in the event of an outbreak. Please turn over to find out more. What to look 1 out for 2 ◆ Marginal leaf scorch 1 ◆ Leaf chlorosis 2 ◆ Premature loss of leaves 3 ◆ Matchstick petioles 3 ◆ Irregular cane maturation (green islands in stems) 4 ◆ Fruit drying and wilting 5 ◆ Stunting of new shoots 5 ◆ Death of plant in 1–5 years Where is the plant from? 3 ◆ Plants sourced from infected countries are at a much higher risk of carrying the disease-causing bacterium Do not panic! 4 How long There are other reasons for disease symptoms to appear. Consider California. of University Montpellier; watercolour, RHS Lindley Collections; “healthy”, RHS / Tim Sandall; “diseased”, J. Clark, California 3 J. Clark & A.H. Purcell, University of California 4 J. Clark, University of California 5 ENSA, Images © 1 M. -

Grape Basics

Grape Basics s – any c ll grape olor – A vitamins C Shop and Save ntain and K co < For eating fresh, choose h help heal cu whic ts. table grapes. They have thinner skins and are sweet and juicy. Grapes grown for juice or wine have thicker skins and much Raisins more sugar. < Depending on the variety of < Look for firm, plump grapes grape, raisins (dried grapes) that are firmly attached to become dark brown or golden. green, flexible stems. < Look for tightly-sealed < Avoid grapes that are containers or covered bulk shriveled, sticky, have brown bins. Raisins should feel soft spots, or with dry, brittle and pliable. stems. < Store raisins in an airtight < Grapes are commonly purple, container in a cool, dry, dark red or pale green. They may place. be seedless or have seeds. Try < different colors, sizes and Once opened, reseal the textures by choosing the variety package tightly to help prevent that is lowest in price. hardening. For best quality use within 6 months. < If raisins become hard, soak in hot liquid for 5 to 15 minutes. Drain and use. < It takes 1 cup of grapes to make ¼ cup of raisins. They Store Well both have about 100 calories. Waste Less M Whole grapes are a I Leave grapes on the stem but remove any grapes that are serious choking hazard for shriveled, brown, or moldy. perforated plastic bag. For best children younger than four I Grapes can be kept on the quality, use within 7 to 10 days. years old. Cut grapes in countertop for a day or two, but I Rinse under cool water just half lengthwise or even last longer when refrigerated. -

OSU Wine and Grape Research and Extension Newsletter February 2010

OSU Wine and Grape Research and Extension Newsletter February 2010 http://wine.oregonstate.edu In this issue: Welcome to the February 2010 Newsletter Welcome As the dormant season progresses towards the beginning of the 2010 vineyard season, we prepared this newsletter to focus on viticulture topics in disease management and cover Avoiding canker problems in cropping. the vineyard With pruning taking place across vineyards in Oregon, Dr. Jay Pscheidt reminds vineyard managers to be on alert for canker diseases. Also, as we prepare for this next season, OSU OSU Plant Clinic announces Plant Clinic is preparing for new diagnostic testing services for grape viruses. To round off the vineyard pest management sections of this newsletter, Dr. Amy Dreves provides an new grape virus testing updated report on the Spotted Wing Drosophila and the impacts in vineyards. Using cover crops as a tool in For those of you who participated in past OSU surveys, you can read a summary of a cover crop survey conducted in 2008-2009. Within that report, Dr. Patty Skinkis provides vineyard management an update on current cover crop research results. Finally, take a moment to check out upcoming events for winter 2010 and the newly What do we know about the released OSU Extension Viticulture publications on mealybug and leafroll monitoring. Spotted wing Drosophila in Cheers, The OSU Winegrape Team Oregon? Avoiding canker problems in the vineyard Oregon State University to Dr. Jay W. Pscheidt, OSU Extension Plant Pathology Specialist feature viticulture and enology A canker is a dead area of a vine generally found on a trunk or cordon. -

So You Want to Grow Grapes in Tennessee

Agricultural Extension Service The University of Tennessee PB 1689 So You Want to Grow Grapes in Tennessee 1 conditions. American grapes are So You Want to Grow versatile. They may be used for fresh consumption (table grapes) or processed into wine, juice, jellies or Grapes in Tennessee some baked products. Seedless David W. Lockwood, Professor grapes are used mostly for fresh Plant Sciences and Landscape Systems consumption, with very little demand for them in wines. Yields of seedless varieties do not match ennessee has a long history of grape production. Most recently, those of seeded varieties. They are T passage of the Farm Winery Act in 1978 stimuated an upsurge of also more susceptible to certain interest in grape production. If you are considering growing grapes, the diseases than the seeded American following information may be useful to you. varieties. French-American hybrids are crosses between American bunch 1. Have you ever grown winery, the time you spend visiting and V. vinifera grapes. Their grapes before? others will be a good investment. primary use is for wine. uccessful grape production Vitis vinifera varieties are used S requires a substantial commit- 3. What to grow for wine. Winter injury and disease ment of time and money. It is a American problems seriously curtail their marriage of science and art, with a - seeded growth in Tennessee. good bit of labor thrown in. While - seedless Muscadines are used for fresh our knowledge of how to grow a French-American hybrid consumption, wine, juice and jelly. crop of grapes continues to expand, Vitis vinifera Vines and fruits are not very we always need to remember that muscadine susceptible to most insects and some crucial factors over which we Of the five main types of grapes diseases. -

Grapevine Survey for Viruses of Potential Economic Importance in Norton, Chardonel, and Vignoles

Grapevine Survey for viruses of potential economic importance in Norton, Chardonel, and Vignoles James E. Schoelz Dean Volenberg Division of Plant Sciences University of Missouri Columbia MO The 2017 virus survey: Missouri vineyards tested for the presence of 26 different viruses 25 hybrid grape cultivars tested 400 samples collected in July through a prearranged pattern to avoid bias towards selection of virus-infected plants Each sample was a composite of 4 vines (for a total of 1600 vines sampled) Each sample tested for 26 different viruses Table 2. Virus incidence in each cultivar Muscat Survey Average Survey Valvin Cabernet franc Cabernet Traminette Cloeta Vidal blanc Vignoles Chardonel Norton Vivant Vincent Catawba Rayon Saperavi Noiret Viognier Foch Crimson Cabernet Concord Cayuga Chambourcin Muench Lenior Wetumka Albania Virus Hidalgo GRSPaV3 58.71 100 100 46.7 0 100 100 0 15.0 80.0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 36.4 0 0 100 100 100 0 100 100 GLRaV-3 52.7 91.1 88.5 33.3 85.0 3.3 10.0 0 10.0 0 100 40.0 100 40.0 100 100 0 0 100 50.0 50.0 0 0 0 0 100 GRBV 35.0 24.4 4.3 75.5 77.5 26.7 40.0 90.0 0 0 20.0 100 20.0 80.0 0 100 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 60.0 20.0 100 GVE 31.0 26.7 85.7 8.9 30.0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 100 40.0 100 100 0 0 80.0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 GLRaV-2 19.0 91.1 54.2 6.7 0 26.7 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 20.0 0 0 0 0 0 GVB 17.2 0 65.7 0 22.5 0 0 0 0 0 10.0 60.0 40.0 0 20.0 100 0 0 80.0 0 10.0 0 0 0 0 0 GVkV 13.5 28.9 38.5 0 15.0 3.3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 40.0 0 0 0 0 40.0 GLRaV- 9.2 0 1.4 0 72.5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 60.0 0 0 0 0 0 2RG GVCV 8.2 33.3 1.4 24.4 0 0 20.0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 10.0 0 0 0 10.0 10.0 0 GVA 0.5 0 0 0 2.5 3.3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 GLRaV-5 0.2 0 0 2.2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Sample #2 400 45 70 45 40 30 20 10 20 10 10 5 5 5 5 5 5 11 5 10 10 4 5 10 10 5 1This value is the percentage of the composite samples positive for the selected virus. -

Starting a Vineyard in Texas • a GUIDE for PROSPECTIVE GROWERS •

Starting a Vineyard in Texas • A GUIDE FOR PROSPECTIVE GROWERS • Authors Michael C ook Viticulture Program Specialist, North Texas Brianna Crowley Viticulture Program Specialist, Hill Country Danny H illin Viticulture Program Specialist, High Plains and West Texas Fran Pontasch Viticulture Program Specialist, Gulf C oast Pierre Helwi Assistant Professor and Extension Viticulture Specialist Jim Kamas Associate Professor and Extension Viticulture Specialist Justin S cheiner Assistant Professor and Extension Viticulture Specialist The Texas A&M University System Who is the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service? We are here to help! The Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service delivers research-based educational programs and solutions for all Texans. We are a unique education agency with a statewide network of professional educators, trained volunteers, and county offices. The AgriLife Viticulture and Enology Program supports the Texas grape and wine industry through technical assistance, educational programming, and applied research. Viticulture specialists are located in each region of the state. Regional Viticulture Specialists High Plains and West Texas North Texas Texas A&M AgriLife Research Denton County Extension Office and Extension Center 401 W. Hickory Street 1102 E. Drew Street Denton, TX 76201 Lubbock, TX 79403 Phone: 940.349.2896 Phone: 806.746.6101 Hill Country Texas A&M Viticulture and Fruit Lab 259 Business Court Gulf Coast Fredericksburg, TX 78624 Texas A&M Department of Phone: 830.990.4046 Horticultural Sciences 495 Horticulture Street College Station, TX 77843 Phone: 979.845.8565 1 The Texas Wine Industry Where We Have Been Grapes were first domesticated around 6 to 8,000 years ago in the Transcaucasia zone between the Black Sea and Iran. -

Growing Grapes in Missouri

MS-29 June 2003 GrowingGrowing GrapesGrapes inin MissouriMissouri State Fruit Experiment Station Missouri State University-Mountain Grove Growing Grapes in Missouri Editors: Patrick Byers, et al. State Fruit Experiment Station Missouri State University Department of Fruit Science 9740 Red Spring Road Mountain Grove, Missouri 65711-2999 http://mtngrv.missouristate.edu/ The Authors John D. Avery Patrick L. Byers Susanne F. Howard Martin L. Kaps Laszlo G. Kovacs James F. Moore, Jr. Marilyn B. Odneal Wenping Qiu José L. Saenz Suzanne R. Teghtmeyer Howard G. Townsend Daniel E. Waldstein Manuscript Preparation and Layout Pamela A. Mayer The authors thank Sonny McMurtrey and Katie Gill, Missouri grape growers, for their critical reading of the manuscript. Cover photograph cv. Norton by Patrick Byers. The viticulture advisory program at the Missouri State University, Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center offers a wide range of services to Missouri grape growers. For further informa- tion or to arrange a consultation, contact the Viticulture Advisor at the Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center, 9740 Red Spring Road, Mountain Grove, Missouri 65711- 2999; telephone 417.547.7508; or email the Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center at [email protected]. Information is also available at the website http://www.mvec-usa.org Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction.................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2 Considerations in Planning a Vineyard ........................................................ -

Does Wine Have a Place in Kant's Theory of Taste?1

Does Wine Have a Place in Kant’s Theory of Taste?1 Rachel Cristy, Princeton University Kant’s own answer to my title question is “no.” One can make of a wine the merely subjective judgment that it is agreeable, never the universally valid judgment that it is beautiful. Here is Kant’s only remark on wine in the Critique of the Power of Judgment: With regard to the agreeable, everyone is content that his judgment, which he grounds on a private feeling, and in which he says of an object that it pleases him, be restricted merely to his own person. Hence he is perfectly happy if, when he says that sparkling wine from the Canaries is agreeable, someone else should improve his expression and remind him that he should say “It is agreeable to me”; and this is so not only in the case of the taste of the tongue, palate, and throat, but also in the case of that which may be agreeable to someone’s eyes and ears. (KU §7, 5: 212) Here is Kant’s explanation for why wine can’t be judged beautiful: “Aesthetic judgments can be divided into empirical and pure. The first are those which assert agreeableness or disagreeableness, the second those which assert beauty of an object… the former are judgments of sense (material aesthetic judgments), the latter (as formal) are alone proper judgments of taste” (§14, 5: 223). Not only flavors and aromas, but also “mere color, e.g., the green of a lawn” and “mere tone…say that of a violin” are relegated to judgments of agreeableness, because they “have as their ground merely the matter of the representations, namely mere sensation” (§14, 5: 224). -

Matching Grape Varieties to Sites Are Hybrid Varieties Right for Oklahoma?

Matching Grape Varieties to Sites Are hybrid varieties right for Oklahoma? Bruce Bordelon Purdue University Wine Grape Team 2014 Oklahoma Grape Growers Workshop 2006 survey of grape varieties in Oklahoma: Vinifera 80%. Hybrids 15% American 7% Muscadines 1% Profiles and Challenges…continued… • V. vinifera cultivars are the most widely grown in Oklahoma…; however, observation and research has shown most European cultivars to be highly susceptible to cold damage. • More research needs to be conducted to elicit where European cultivars will do best in Oklahoma. • French-American hybrids are good alternatives due to their better cold tolerance, but have not been embraced by Oklahoma grape growers... Reasons for this bias likely include hybrid cultivars being perceived as lower quality than European cultivars, lack of knowledge of available hybrid cultivars, personal preference, and misinformation. Profiles and Challenges…continued… • The unpredictable continental climate of Oklahoma is one of the foremost obstacles for potential grape growers. • It is essential that appropriate site selection be done prior to planting. • Many locations in Oklahoma are unsuitable for most grapes, including hybrids and American grapes. • Growing grapes in Oklahoma is a risky endeavor and minimization of potential loss by consideration of cultivar and environmental interactions is paramount to ensure long-term success. • There are areas where some European cultivars may succeed. • Many hybrid and American grapes are better suited for most areas of Oklahoma than -

Phylogenetic Analysis of Vitaceae Based on Plastid Sequence Data

PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF VITACEAE BASED ON PLASTID SEQUENCE DATA by PAUL NAUDE Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MAGISTER SCIENTAE in BOTANY in the FACULTY OF SCIENCE at the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG SUPERVISOR: DR. M. VAN DER BANK December 2005 I declare that this dissertation has been composed by myself and the work contained within, unless otherwise stated, is my own Paul Naude (December 2005) TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Abstract iii Index of Figures iv Index of Tables vii Author Abbreviations viii Acknowledgements ix CHAPTER 1 GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Vitaceae 1 1.2 Genera of Vitaceae 6 1.2.1 Vitis 6 1.2.2 Cayratia 7 1.2.3 Cissus 8 1.2.4 Cyphostemma 9 1.2.5 Clematocissus 9 1.2.6 Ampelopsis 10 1.2.7 Ampelocissus 11 1.2.8 Parthenocissus 11 1.2.9 Rhoicissus 12 1.2.10 Tetrastigma 13 1.3 The genus Leea 13 1.4 Previous taxonomic studies on Vitaceae 14 1.5 Main objectives 18 CHAPTER 2 MATERIALS AND METHODS 21 2.1 DNA extraction and purification 21 2.2 Primer trail 21 2.3 PCR amplification 21 2.4 Cycle sequencing 22 2.5 Sequence alignment 22 2.6 Sequencing analysis 23 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 3 RESULTS 32 3.1 Results from primer trail 32 3.2 Statistical results 32 3.3 Plastid region results 34 3.3.1 rpL 16 34 3.3.2 accD-psa1 34 3.3.3 rbcL 34 3.3.4 trnL-F 34 3.3.5 Combined data 34 CHAPTER 4 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS 42 4.1 Molecular evolution 42 4.2 Morphological characters 42 4.3 Previous taxonomic studies 45 4.4 Conclusions 46 CHAPTER 5 REFERENCES 48 APPENDIX STATISTICAL ANALYSIS OF DATA 59 ii ABSTRACT Five plastid regions as source for phylogenetic information were used to investigate the relationships among ten genera of Vitaceae. -

Wine Grape Terminology- the Lingo of Viticulture

Wine Grape Terminology- The Lingo of Viticulture Dr. Duke Elsner Small Fruit Educator Michigan State University Extension Traverse City, Michigan 2014 Wine Grape Vineyard Establishment Conference Viticulture Terminology Where to start? How far to go? – Until my time runs out! What are grapes? “…thornless, dark-stemmed, green- flowered, mostly shreddy-barked, high-climbing vines that climb by means of tendrils.” Cultivated species of grapes Vitis labrusca – Native to North America – Procumbent shoot growth habit – Concord, Niagara, dozens more Vitis vinifera – Eastern Europe, middle east – Upright shoot growth habit – Riesling, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Gewurztraminer, etc. Other important species of grapes Vitis aestivalis Summer grape Vitis riparia Riverbank grape Vitis rupestris Sand grape Vitis rotundifolia Muscadine grape Vitis cinerea Winter grape Variety A varient form of a wild plant that has been recognized as a true taxon ranking below sub- species. Cultivar A variety of a plant species originating and continuing in cultivation and given a name in modern language. Hybrid Cultivar A new cultivar resulting from the intentional crossing of selected cultivars, varieties or species. Hybrid Cultivar A new cultivar resulting from the intentional crossing of selected cultivars, varieties or species. Clone (clonal selection) A strain of grape cultivar that has been derived by asexual reproduction and presumably has a desirable characteristic that sets it apart from the “parent” variety. Pinot Noir = cultivar Pinot Noir Pommard = clone Grafted vine A vine produced by a “surgical” procedure that connects one or more desired fruiting cultivars onto a variety with desired root characteristics. Scion Above-graft part of a grafted vine, including leaf and fruit-bearing parts. -

Grape Varieties for Indiana

Commercial • HO-221-W Grape Varieties for Indiana COMMERCIAL HORTICULTURE • DEPARTMENT OF HORTICULTURE PURDUE UNIVERSITY COOPERATIVE EXTENSION SERVICE • WEST LAFAYETTE, IN Bruce Bordelon Selection of the proper variety is a major factor for fungal diseases than that of Concord (Table 1). Catawba successful grape production in Indiana. Properly match- also experiences foliar injury where ozone pollution ing the variety to the climate of the vineyard site is occurs. This grape is used primarily in white or pink necessary for consistent production of high quality dessert wines, but it is also used for juice production and grapes. Grape varieties fall into one of three groups: fresh market sales. This grape was widely grown in the American, French-American hybrids, and European. Cincinnati area during the mid-1800’s. Within each group are types suited for juice and wine or for fresh consumption. American and French-American Niagara is a floral, strongly labrusca flavored white grape hybrid varieties are suitable for production in Indiana. used for juice, wine, and fresh consumption. It ranks The European, or vinifera varieties, generally lack the below Concord in cold hardiness and ripens somewhat necessary cold hardiness to be successfully grown in earlier. On favorable sites, yields can equal or surpass Indiana except on the very best sites. those of Concord. Acidity is lower than for most other American varieties. The first section of this publication discusses American, French-American hybrids, and European varieties of wine Other American Varieties grapes. The second section discusses seeded and seedless table grape varieties. Included are tables on the best adapted varieties for Indiana and their relative Delaware is an early-ripening red variety with small berries, small clusters, and a mild American flavor.