Is Religiosity of Immigrants a Bridge Or a Buffer in the Process of Integration? a Comparative Study of Europe and the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Church of England Clergy Advocates (CECA) and the (Ncis) National Church Institutions

Church of England Clergy Advocates (CECA) and the (NCIs) National Church Institutions CECA is a workplace grouping of all Church of England clergy who are members of Unite Faith Workers Branch of Unite. The Faith Workers Branch (FWB) includes ministers and workers of all denominations as well as other faiths, and covers all of the UK. How CECA work with the NCIs CECA and the NCIs engage constructively with senior organisational representatives (usually from Clergy HR and Ministry Division meeting with CECA representatives) three times a year to discuss issues of concern. CECA and the Remuneration and Conditions of Service Committee share a number of common areas of interest and CECA representatives are invited to attend a meeting of RACSC annually in order to provide their input on relevant matters. How does CECA support office holders and church workers? • National helpline for members, staffed by experienced volunteers • A network of Accredited Representatives provides advice, support, and representation. • Regional Co-coordinators provide fellowship, encouragement, information and training. • Offer general advice, education and fellowship to member clergy through national and regional meetings, publications, or in other appropriate ways. • Represent the needs and concerns of members within the structures of the Church of England. Our shared priorities • Fairness and dignity • Best practice in policy and practise within the clergy context • Clear conditions of office Membership of CECA All clergy are entitled to be a member of a Trades Union or Professional Association and this is a matter for individual decision. Members of a Trades Union or Professional Association may be represented in matters affecting them as individuals by their Trades Union or Professional Association representative. -

HINDUISM in EUROPE Stockholm 26-28 April, 2017 Abstracts

HINDUISM IN EUROPE Stockholm 26-28 April, 2017 Abstracts 1. Vishwa Adluri, Hunter College, USA Sanskrit Studies in Germany, 1800–2015 German scholars came late to Sanskrit, but within a quarter century created an impressive array of faculties. European colleagues acknowledged Germany as the center of Sanskrit studies on the continent. This chapter examines the reasons for this buildup: Prussian university reform, German philological advances, imagined affinities with ancient Indian and, especially, Aryan culture, and a new humanistic model focused on method, objectivity, and criticism. The chapter’s first section discusses the emergence of German Sanskrit studies. It also discusses the pantheism controversy between F. W. Schlegel and G. W. F. Hegel, which crucially influenced the German reception of Indian philosophy. The second section traces the German reception of the Bhagavad Gītā as a paradigmatic example of German interpretive concerns and reconstructive methods. The third section examines historic conflicts and potential misunderstandings as German scholars engaged with the knowledge traditions of Brahmanic Hinduism. A final section examines wider resonances as European scholars assimilated German methods and modeled their institutions and traditions on the German paradigm. The conclusion addresses shifts in the field as a result of postcolonial criticisms, epistemic transformations, critical histories, and declining resources. 2. Milda Ališauskienė, Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania “Strangers among Ours”: Contemporary Hinduism in Lithuania This paper analyses the phenomenon of contemporary Hinduism in Lithuania from a sociological perspective; it aims to discuss diverse forms of Hindu expression in Lithuanian society and public attitudes towards it. Firstly, the paper discusses the history and place of contemporary Hinduism within the religious map of Lithuania. -

Fewer Americans Affiliate with Organized Religions, Belief and Practice Unchanged

Press summary March 2015 Fewer Americans Affiliate with Organized Religions, Belief and Practice Unchanged: Key Findings from the 2014 General Social Survey Michael Hout, New York University & NORC Tom W. Smith, NORC 10 March 2015 Fewer Americans Affiliate with Organized Religions, Belief and Practice Unchanged: Key Findings from the 2014 General Social Survey March 2015 Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Most Groups Less Religious ....................................................................................................................... 3 Changes among Denominations .................................................................................................................. 4 Conclusions and Future Work....................................................................................................................... 5 About the Data ............................................................................................................................................. 6 References ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 About the Authors ....................................................................................................................................... -

Top 5 Myths of the Separation of Church and State

Top 5 myths of the separation of church and state Brent Walker BJC Executive Director, 1999-2016 Myth #1: We don’t have separation of church and state in America because those words are not in the Constitution. True, the words are not there, but the principle surely is. It is much too glib an argument to say that constitutional principles depend on the use of certain words. Who would deny that “federalism,” “separation of powers” and the “right to a fair trial” are constitutional principles? But those words do not appear in the Constitution either. The separation of church and state, or the “wall of separation,” is simply a metaphor, a shorthand way of expressing a deeper truth that religious liberty is best protected when church and state are institutionally separated and neither tries to perform or interfere with the essential mission and work of the other. We Baptists often hold up Roger Williams’ “hedge or wall of separation between the garden of the church and the wilderness of the world,” and point to Thomas Jefferson’s 1802 Letter to the Danbury Connecticut Baptist Association where he talked about his “sovereign reverence” for the “wall of separation.” But we sometimes overlook the writings of the father of our Constitution, James Madison, who observed that “the number, the industry and the morality of the priesthood and the devotion of the people have been manifestly increased by the total separation of church and state.”1 Even Alexis de Tocqueville, in his famed 19th-century “Democracy in America,” a work often cited by those who would disparage separation, writes favorably of it: “In France, I had seen the spirits of religion and freedom almost always marching in opposite directions. -

Separation of Church and State: a Diffusion of Reason and Religion

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2006 Separation of Church and State: A Diffusion of Reason and Religion. Patricia Annettee Greenlee East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Greenlee, Patricia Annettee, "Separation of Church and State: A Diffusion of Reason and Religion." (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2237. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2237 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Separation of Church and State: A Diffusion of Reason and Religion _________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University __________________ In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _________________ by Patricia A. Greenlee August, 2006 _________________ Dr. Dale Schmitt, Chair Dr. Elwood Watson Dr. William Burgess Jr. Keywords: Separation of Church and State, Religious Freedom, Enlightenment ABSTRACT Separation of Church and State: A Diffusion of Reason and Religion by Patricia A.Greenlee The evolution of America’s religious liberty was birthed by a separate church and state. As America strides into the twenty first century the origin of separation of church and state continues to be a heated topic of debate. -

Relationships Between Religious Denomination, Quality of Life

Journal of Global Catholicism Volume 2 Article 3 Issue 1 African Catholicism: Retrospect and Prospect December 2017 Relationships Between Religious Denomination, Quality of Life, Motivation and Meaning in Abeokuta, Nigeria Mary Gloria Njoku Godfrey Okoye University, [email protected] Babajide Gideon Adeyinka ICT Polytechnic Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc Part of the African Studies Commons, Anthropology Commons, Catholic Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Community Psychology Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Developmental Psychology Commons, Health Psychology Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Multicultural Psychology Commons, Personality and Social Contexts Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, and the Transpersonal Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Njoku, Mary Gloria and Adeyinka, Babajide Gideon (2017) "Relationships Between Religious Denomination, Quality of Life, Motivation and Meaning in Abeokuta, Nigeria," Journal of Global Catholicism: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 3. p.24-51. DOI: 10.32436/2475-6423.1020 Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc/vol2/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Catholicism by an authorized editor of CrossWorks. 34 MARY GLORIA C. NJOKU AND BABAJIDE GIDEON ADEYINKA Relationships Between Religious Denomination, Quality of Life, Motivation and Meaning in Abeokuta, Nigeria Mary Gloria C. Njoku holds a masters and Ph.D. in clinical psychology and an M.Ed. in information technology. She is a professor and the dean of the School of Postgraduate Studies and the coordinator of the Interdisciplinary Sustainable Development Research team at Godfrey Okoye University Enugu, Nigeria. -

Sport, Islam, and Muslims in Europe: in Between Or on the Margin?

Religions 2013, 4, 644–656; doi:10.3390/rel4040644 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article Sport, Islam, and Muslims in Europe: in between or on the Margin? Mahfoud Amara School of Sport, Exercise and Health Sciences, Loughborough University, Loughborough, Leicestershire, LE11 3TU, UK; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-0-1509-226370; Fax: +44-0-1509-226301 Received: 30 September 2013; in revised form: 30 November 2013 / Accepted: 4 December 2013 / Published: 10 December 2013 Abstract: The aim of this paper is to reveal how misconceptions—or using the concept of Arkoun, “the crisis of meanings”—about the role and position of Islam in Europe is impacting on the discourse on sport, Islam, and immigration. France is selected as a case study for this paper as it is in this country where the debate on religion in general and Islam in particular seem to be more contentious in relation to the questions of integration of Muslim communities to secular (French republican) values. Recent sources of tensions include the ban of the Burqa in the public space; the debate on national identity instigated by the former French president Nicholas Sarkozy, which became centred around the question of Islam and Muslims in France; the provocative cartoons about Prophet Mohamed in the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo; opposition against the provision of halal meal in France’s fast-food chain Quick; and resistance toward Qatar’s plan to invest in deprived suburbs of France, to name just a few. The other context which this paper examines in relation to the question of sport, Islam, and identity-making of Muslims in Europe is the phenomenon of “reverse migration” or the re-connection of athletes of Muslim background in Europe, or so-called Muslim neo-Europeans, with their (parents’) country of origin. -

Christianity Questions

Roman Catholics of the Middle Ages shared the belief that there was Name one God, and that he created the universe. They believed that God sent his son, Jesus, to Earth to save mankind. They believed that God wanted his people to meet for worship. They believed that it was their religious duty to convert others to Christianity. Christianity Roman Catholics believed in the Bible - both the Old Testament, By Sharon Fabian which dated back to the time before Jesus was born, and the New Testament, which contained Jesus' teachings as told by his apostles. When you look at a picture of a medieval town, what do you see at the town's center? Often, you Their beliefs led to several developments, which have become part of will see a Christian cathedral. With its tall spires the history of the Middle Ages. One was the building of magnificent reaching toward heaven, the cathedral cathedrals for worship. Another was the Crusades, military campaigns dominated the landscape in many small towns of to take back Palestine, the Christian "Holy Land," from the Muslims. the Middle Ages. This is not a surprise, since A third development was the creation of religious orders of monks Christianity was the dominant religion in Europe and nuns who made it their career to do the work of the Church. during that time. The Roman Catholic Church continued to dominate religious life in Christianity was not the only religion in Europe Europe throughout the Middle Ages, but as the Middle Ages declined, in the Middle Ages. There were Jews, Muslims, so did the power of the Church. -

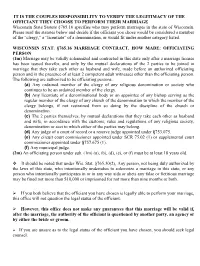

It Is the Couples Responsibility to Verify the Legitimacy Of

IT IS THE COUPLES RESPONSIBILITY TO VERIFY THE LEGITIMACY OF THE OFFICIANT THEY CHOOSE TO PERFORM THEIR MARRIAGE Wisconsin State Statute §765.16 specifies who may perform marriages in the state of Wisconsin. Please read the statutes below and decide if the officiant you chose would be considered a member of the “clergy,” a “licentiate” of a denomination, or would fit under another category listed. WISCONSIN STAT. §765.16 MARRIAGE CONTRACT, HOW MADE: OFFICIATING PERSON (1m) Marriage may be validly solemnized and contracted in this state only after a marriage license has been issued therefor, and only by the mutual declarations of the 2 parties to be joined in marriage that they take each other as husband and wife, made before an authorized officiating person and in the presence of at least 2 competent adult witnesses other than the officiating person. The following are authorized to be officiating persons: (a) Any ordained member of the clergy of any religious denomination or society who continues to be an ordained member of the clergy. (b) Any licentiate of a denominational body or an appointee of any bishop serving as the regular member of the clergy of any church of the denomination to which the member of the clergy belongs, if not restrained from so doing by the discipline of the church or denomination. (c) The 2 parties themselves, by mutual declarations that they take each other as husband and wife, in accordance with the customs, rules and regulations of any religious society, denomination or sect to which either of the parties may belong. -

Church-State Relationships in Europe

RESEARCH REPORT ON CHURCH-STATE RELATIONSHIPS IN SELECTED EUROPEAN COUNTRIES Nick Haynes, MA (Hons), IHBC Historic Buildings Consultant June 2008 Commissioned by the Historic Environment Advisory Council for Scotland (HEACS) Research Report on Church-State Relationships in Selected European Countries Prepared by Nick Haynes, Historic Buildings Consultant. Commissioned by the Historic Environment Advisory Council for Scotland (HEACS) June 2008 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................3 2. LIMITATIONS ......................................................................................................................................3 3. SUMMARY .........................................................................................................................................4 4. EUROPEAN CHURCH-STATE RELATIONSHIPS ...................................................................................4 5. EUROPEAN POLICY CONTEXT .........................................................................................................4 6. SCOTLAND .......................................................................................................................................6 7. ENGLAND .........................................................................................................................................9 8. FRANCE ..........................................................................................................................................14 -

Introduction to the 2018 Convocation for Restoration

Introduction to the 2018 Convocation for Restoration and Renewal of the Undivided Church: Through a renewed Catholicity – Dublin, Ireland – March 2018 The Polish National Catholic Church and the Declaration and Union of Scranton by the Very Rev. Robert M. Nemkovich Jr. The Polish National Catholic Church promulgated the Declaration of Scranton in 2008 to preserve true and genuine Old Catholicism and allow for a Union of Churches that would be a beacon for and home to people of all nations who aspire to union with the pristine faith of the undivided Church. The Declaration of Scranton “is modeled heavily on the 1889 Declaration of Utrecht of the Old Catholic Churches. This is true not only in its content, but also in the reason for its coming to fruition.”1 The Polish National Catholic Church to this day holds the Declaration of Utrecht as a normative document of faith. To understand the origins of the Declaration of Utrecht we must look back not only to the origin of the Old Catholic Movement as a response to the First Vatican Council but to the very see of Utrecht itself. “The bishopric of Utrecht, which until the sixteenth century had been the only bishopric in what is now Dutch territory, was founded by St. Willibrord, an English missionary bishop from Yorkshire.”2 Willibrord was consecrated in Rome by Pope Sergius I in 696, given the pallium of an archbishop and given the see of Utrecht by Pepin, the Mayor of the Palace of the Merovingian dynasty. Utrecht became under Willibrord the ecclesiastical capital of the Northern Netherlands. -

The Messenger

S E P T E M B E R 2 0 2 1 NATIONAL UNITED METHODIST CHURCH THE MESSENGER www.nationalchurch.org September 11th Remembrance IN THIS ISSUE Autumn Worship Pages 2-3 Silence the Violence Honk Jr. Page 4 Food for Thought page 5 You are invited to a Prayer & Meditation Service commemorating the 20th year anniversary of the 9/11 tragedy. The Metropolitan Memorial Garden @ St.Lukes Update sanctuary will be open from 5-8 pm on Saturday, September 11 for you to Farm Market Recovery participate in individual experiential prayer stations at your own pace. Page 6 Learning Opportunities Our clergy will be available for personal prayer throughout the evening. A Pages 7-9 short communal liturgy will be offered on the portico at the beginning of UMW Sunday each hour. The meditation stations will be open throughout the 5-8 pm Page 10 timeframe. You are welcome to come just as you are, whatever you are feeling (or not feeling) as you recall the events of 9/11 and beyond. You Jazz@Wesley Page 10-11 can come for 5 minutes or stay the whole time. All are welcome. If you have any questions, please contact Pastor Ali DeLeo ([email protected] | 202-744-6440). An Invitation to Autumn Worship from Pastor Doug The outdoor worship service at Metropolitan Memorial was drawing to a close when this bright yellow butterfly hovered overhead during one of the hymns. A bumblebee had passed earlier in more of a direct line, but this butterfly seemed to linger there as the hymn “In Christ Alone” echoed across campus.