PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

04 July 2020

04 July 2020 12:01 AM John Philip Sousa (1854-1932) Stars & Stripes forever – March Netherlands Radio Symphony Orchestra, Richard Dufallo (conductor) NLNOS 12:05 AM Thomas Demenga (1954-) Summer Breeze Andrea Kolle (flute), Maria Wildhaber (bassoon), Sarah Verrue (harp) CHSRF 12:13 AM Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Concerto in C major, RV.444 for recorder, strings & continuo Il Giardino Armonico, Giovanni Antonini (recorder), Giovanni Antonini (director), Enrico Onofri (violin), Marco Bianchi (violin), Duilio Galfetti (violin), Paolo Beschi (cello), Paolo Rizzi (violone), Luca Pianca (theorbo), Gordon Murray (harpsichord), Duilio Galfetti (viola) DEWDR 12:23 AM Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) 3 Chansons for unaccompanied chorus BBC Singers, Alison Smart (soprano), Judith Harris (mezzo soprano), Daniel Auchincloss (tenor), Stephen Charlesworth (baritone), Stephen Cleobury (conductor) GBBBC 12:30 AM Bela Bartok (1881-1945) Out of Doors, Sz.81 David Kadouch (piano) PLPR 12:44 AM Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Rosamunde (Ballet Music No 2), D 797 Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, Heinz Holliger (conductor) NONRK 12:52 AM John Cage (1912-1992) In a Landscape Fabian Ziegler (percussion) CHSRF 01:02 AM Jean-Francois Dandrieu (1682-1738) Rondeau 'L'Harmonieuse' from Pieces de Clavecin Book I Colin Tilney (harpsichord) CACBC 01:08 AM Bohuslav Martinu (1890-1959) The Frescoes of Piero della Francesca Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, Robert Stankovsky (conductor) SKSR 01:30 AM Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Metamorphosen for 23 solo strings (AV.142) Risor Festival Strings, -

Paul Weller with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Jules Buckley

For immediate release Paul Weller with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Jules Buckley concert date added to ‘Live from the Barbican’ line-up in spring 2021 Barbican Hall, Saturday 6 February 2021, 8pm The Barbican and Barbican Associate Orchestra, the BBC Symphony Orchestra are excited to announce that the orchestra and its Creative Artist in Association Jules Buckley, will be joined by legendary singer songwriter Paul Weller on Saturday 6 February for a concert reimagining Weller’s work in stunning orchestral settings as part of Live from the Barbican in 2021. In Weller’s first live performance for two years, songs spanning the broad spectrum of his career from The Jam to as yet unheard new material will delight fans and newcomers alike. Classic songs including ‘You Do Something to Me’, ‘English Rose’ and ‘Wild Wood’ along with tracks from Weller’s latest number 1 album ‘On Sunset’ will be heard as never before in brand new orchestral arrangements by Buckley. Weller, who takes cultural authenticity to the top of the charts, reunites with Steve Cradock for this one-off performance. Part of the acclaimed Live from the Barbican series which returns to the Centre in the spring, the concert will have a reduced, socially distanced live audience in the Barbican Hall, and it will also be available to watch globally via a livestream on the Barbican website. Whilst the concert will reflect on some of Weller’s back catalogue, as is typical of his constantly evolving career, it will look to the future with performances of songs from an album not released until May 2021, as well as welcoming guest artists to illustrate his work and the music that influenced him. -

9445.01 GCE A2 Music (Part 2) Written Paper (Summer 2015).Indd

ADVANCED General Certificate of Education 2015 Music Assessment Unit A2 2: Part 2 assessing Written Examination [AU222] TUESDAY 2 JUNE, AFTERNOON MARK SCHEME 9445.01 F Context for marking Questions 2, 3 and 4 – Optional Areas of Study Each answer should be marked out of 30 marks distributed between the three criteria as follows: Criterion 1 – content focused Knowledge and understanding of the Area of Study applied to the context of the question. [24] Criterion 2 – structure and presentation of ideas Approach to the question, quality of the argument and ideas. [3] Criterion 3 – quality of written communication Quality of language, spelling, punctuation and grammar and use of appropriate musical vocabulary. [3] MARKING PROCESS Knowledge and Understanding of the Area of Study applied to the Context of the Question Marks should be awarded according to the mark bands stated below. Marks [1]–[6] The answer is limited by insufficient breadth or depth of knowledge. [7]–[12] The answer displays some breadth but limited depth of knowledge of the area of study. There is some attempt to relate the content of the answer to the context of the question but there may be insufficient reference to appropriate musical examples. [13]–[18] The answer displays a competent grasp of the area of study in terms of both breadth and depth of knowledge with appropriate musical examples to support points being made or positions taken. At the lower end of the range there may be an imbalance between breadth and depth of knowledge and understanding. [19]–[24] The answer displays a comprehensive grasp of the area of study in terms of both breadth and depth of knowledge and understanding with detailed musical examples and references to musical, social, cultural or historical contexts as appropriate. -

Two Serial Pieces Written in 1968 by Pierre Boulez and Isang Yun By

A Study of Domaines and Riul: Two Serial Pieces Written in 1968 by Pierre Boulez and Isang Yun by Jinkyu Kim Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee _______________________________________ Julian L. Hook, Research Director _______________________________________ James Campbell, Chair _______________________________________ Eli Eban _______________________________________ Kathryn Lukas April 10, 2018 ii Copyright © 2018 Jinkyu Kim iii To Youn iv Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................. v List of Examples ............................................................................................................................. vi List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. ix List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. xi Chapter 1: MUSICAL LANGUAGES AFTER WORLD WAR II ................................................ 1 Chapter 2: BOULEZ, DOMAINES ................................................................................................ -

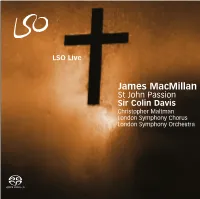

James Macmillan

LSO Live LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk James MacMillan LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les St John Passion plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant Sir Colin Davis ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Christopher Maltman circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres London Symphony Chorus du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns herein: lso.co.uk LSO0671 James MacMillan St John Passion (The Passion of Our Lord Disc 1 – Part I Total 54’14” Jesus Christ According to St John) 1 i. The arrest of Jesus 10’17” p12 Sir Colin Davis London Symphony Orchestra 2 ii. -

Download the Concert Programme (PDF)

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Thursday 18 May 2017 7.30pm Barbican Hall Vaughan Williams Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus Brahms Double Concerto INTERVAL Holst The Planets – Suite Sir Mark Elder conductor Roman Simovic violin Tim Hugh cello Ladies of the London Symphony Chorus London’s Symphony Orchestra Simon Halsey chorus director Concert finishes approx 9.45pm Supported by Baker McKenzie 2 Welcome 18 May 2017 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief Welcome to tonight’s LSO concert at the Barbican. BMW LSO OPEN AIR CLASSICS 2017 This evening we are joined by Sir Mark Elder for the second of two concerts this season, as he conducts The London Symphony Orchestra, in partnership with a programme of Vaughan Williams, Brahms and Holst. BMW and conducted by Valery Gergiev, performs an all-Rachmaninov programme in London’s Trafalgar It is always a great pleasure to see the musicians Square this Sunday 21 May, the sixth concert in of the LSO appear as soloists with the Orchestra. the Orchestra’s annual BMW LSO Open Air Classics Tonight, after Vaughan Williams’ Five Variants of series, free and open to all. Dives and Lazarus, the LSO’s Leader Roman Simovic and Principal Cello Tim Hugh take centre stage for lso.co.uk/openair Brahms’ Double Concerto. We conclude the concert with Holst’s much-loved LSO WIND ENSEMBLE ON LSO LIVE The Planets, for which we welcome the London Symphony Chorus and Choral Director Simon Halsey. The new recording of Mozart’s Serenade No 10 The LSO premiered the complete suite of The Planets for Wind Instruments (‘Gran Partita’) by the LSO Wind in 1920, and we are thrilled that the 2002 recording Ensemble is now available on LSO Live. -

BBC Symphony Orchestra/Oramo

BBC Symphony Orchestra/Oramo Start time: 8pm Approximate running time: 60 minutes, no interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change Programme Anna Clyne Within Her Arms Joseph Haydn Symphony No 49 in F minor, La Passione 1 Adagio 2 Allegro di molto 3 Menuet 4 Finale: Presto Magnus Lindberg Accused Three interrogations for soprano and orchestra, arr chamber orchestra (world premiere) 1 Part 1 2 Part 2 3 Part 3 Emotion and angst is at the forefront of tonight’s BBC Symphony Orchestra programme, as Harriet Smith explains. Tonight’s concert begins with what is arguably Anna Clyne’s most-performed work. Within her Arms is a seminal piece in her musical development for it was the point at which she realised that she was indeed a composer, modestly remarking: ‘That is how I like to express myself’. She is British-born but US-based and the commission for this piece came from the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s Green Umbrella series for young composers. The medium she chose was 15 strings and music she wrote was initially, she recalls, ‘very energetic and chaotic’. All that changed with a phone call and the devastating news that her mother had died unexpectedly. She flew back to England and within a day had recomposed Within her Arms as a heartfelt elegy. There’s an unmistakable sense of the music caressing the listener as the string lines move separately yet harmoniously. The medium itself allows both luminosity and in places a sparseness of texture, which makes the passages where the music builds to a peak of intensity, violins high over low-lying drones, all the more heartrending. -

Middleground Structure in the Cadenza to Boulez's Éclat

Middleground Structure in the Cadenza to Boulez’s Éclat C. Catherine Losada NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hp://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.19.25.1/mto.19.25.1.losada.php KEYWORDS: Boulez, Éclat, multiplication, middleground, transformational theory ABSTRACT: Through a transformational analysis of Boulez’s Éclat, this article extends previous understanding of Boulez’s compositional techniques by addressing issues of middleground structure and perception. Presenting a new perspective on this pivotal work, it also sheds light on the development of Boulez’s compositional style. Volume 25, Number 1, May 2019 Copyright © 2019 Society for Music Theory [1] Incorporating both elements of performer’s choice (mainly for the conductor) and an approach to temporality that subverts traditional notions of continuity by invoking the importance of the “moment,”(1) Boulez’s Éclat (1965) is a landmark work from the mid-1960s. It stems from a pivotal period within Boulez’s compositional career, following a time of intense application of novel serial techniques in works that cemented his reputation as a major figure of European modernism (such as Pli selon pli (1957–1962) and the Troisième Sonate (1955–63),(2) but preceding the marked simplification of the musical language that followed Rituel (1974).(3) Piencikowski (1993) has discussed the reliance of much of the central section of Éclat on material from the first version of Don (1960) which in turn is derived from the flute piece Strophes (1957) and from Orestie (1955), and has also thoroughly explained the pitch content of that central section.(4) The material from the framing cadenzas of Éclat, however, has received lile scholarly aention in published form, although Olivier Meston (2001) provides a description of abstract serial processes that could explain the pitch content.(5) One of Meston’s main claims is that the serial processes he presents are not perceptible (10, 16). -

Mozart: Requiem

LSO Live Mozart Requiem Sir Colin Davis Marie Arnet Anna Stéphany Andrew Kennedy Darren Jeffery London Symphony Chorus London Symphony Orchestra Mozart Requiem, K626 (1791) Page Index Marie Arnet soprano 3 Track listing Anna Stéphany alto 4 English notes Andrew Kennedy tenor 5 French notes Darren Jeffery bass 6 German notes 7 Composer biography Sir Colin Davis conductor 8 Text London Symphony Orchestra 10 Conductor biography London Symphony Chorus 11 Artist biographies 13 Orchestra and Chorus personnel lists 14 LSO biography James Mallinson producer Daniele Quilleri casting consultant Classic Sound Ltd recording, editing and mastering facilities Jonathan Stokes and Neil Hutchinson for Classic Sound Ltd balance engineers Ian Watson and Jenni Whiteside for Classic Sound Ltd editors A high density DSD (Direct Stream Digital) recording Recorded live at the Barbican, London 30 September and 3 October 2007 © 2008 London Symphony Orchestra, London UK P 2008 London Symphony Orchestra, London UK 2 Track listing Introitus and Kyrie 1 No 1 Requiem and Kyrie (chorus, soprano) 7’12’’ p8 Sequence 2 No 2 Dies irae (chorus) 1’44’’ p8 3 No 3 Tuba mirum (soprano, alto, tenor, bass) 3’38’’ p8 4 No 4 Rex tremendae (chorus) 2’13’’ p8 5 No 5 Recordare (soprano, alto, tenor, bass) 6’03’’ p8 6 No 6 Confutatis maledictis (chorus) 2’44’’ p8 7 No 7 Lacrimosa (chorus) 2’59’’ p8 Offertorium 8 No 8 Domine Jesu (chorus, soprano, alto, tenor, bass) 4’16’’ p8 9 No 9 Hostias (chorus) 4’36’’ p9 Sanctus 10 No 10 Sanctus (chorus) 1’47’’ p9 Benedictus 11 No 11 Benedictus (chorus, soprano, alto, tenor, bass) 4’29’’ p9 Agnus Dei and Communio 12 No 12 Agnus Dei (chorus, soprano) 8’46’’ p9 TOTAL 50’35’’ 3 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91) Jesu’ and the ’Hostias’ were written separately. -

Morning Heroes Blissmorning Heroes

SUPER AUDIO CD MORNING HEROES BLISS Hymn to Apollo (original version) Samuel West orator BBC Symphony Chorus BBC Symphony Orchestra SIR ANDREW DaVIS Arthur Bliss,1923 Arthur Photograph by Herbert Lambert (1881 – 1936) / Mary Evans Picture Library Sir Arthur Bliss (1891 – 1975) Morning Heroes, F 32 (1930)* 55:33 A Symphony for Orator, Chorus, and Orchestra To the memory of my brother FRANCIS KENNARD BLISS and all other comrades killed in battle 1 I Hector’s Farewell to Andromache. Maestoso – L’istesso tempo – L’istesso tempo – 13:00 2 II The City Arming. Allegro alla marcia (with great spirit and elation) – Poco meno – Più mosso – Meno mosso (Moderato) – Alla marcia – Più mosso – Pochissimo meno – Andante moderato 11:14 3 III Vigil. Andante sostenuto – L’istesso tempo (Tranquillo) – Agitato – Tempo I – 7:53 4 The Bivouac’s Flame. Adagio maestoso – Più mosso – A tempo maestoso – Tempo I – Largamente 4:26 5 IV Achilles Goes Forth to Battle. Allegro con fuoco – Tranquillo – 6:45 6 The Heroes. Allegro con fuoco – Molto animato 1:38 V Now, Trumpeter, for thy Close 7 Spring Offensive. Andante maestoso – Più animato – Andante molto tranquillo – 5:32 8 Dawn on the Somme. Grave (quasi chorale) – Andante tranquillo – Pochissimo più mosso – Più mosso – Maestoso – Molto tranquillo 5:02 3 premiere recording 9 Hymn to Apollo, F 116 (1926) 9:26 for Orchestra Original version Moderato maestoso – Più mosso (assai allegro) – A tempo I (moderato) – Più mosso – Tranquillo, ma non meno mosso – A tempo I meno mosso TT 65:12 Samuel West orator* BBC Symphony Chorus* Stephen Jackson chorus master BBC Symphony Orchestra Laura Samuel leader Sir Andrew Davis 4 Sir Andrew Davis Andrew Sir © Dario Acosta Photography Bliss: Morning Heroes / Hymn to Apollo Morning Heroes by machine gun fire near barrier.. -

Download Booklet

• • • BAX DYSON VEALE BLISS VIOLIN CONCERTOS Lydia Mordkovitch violin London Philharmonic Orchestra • City of London Sinfonia BBC Symphony Orchestra • BBC National Orchestra of Wales Richard Hickox • Bryden Thomson Nick Johnston Nick Lydia Mordkovitch (1944 – 2014) British Violin Concertos COMPACT DISC ONE Sir Arnold Bax (1883 – 1953) Concerto for Violin and Orchestra* 35:15 1 I Overture, Ballade and Scherzo. Allegro risoluto – Allegro moderato – Poco largamente 14:47 2 II Adagio 11:41 3 III Allegro – Slow valse tempo – Andante con moto 8:45 Sir George Dyson (1883 – 1964) Violin Concerto† 43:14 4 I Molto moderato 20:14 5 II Vivace 5:08 6 III Poco andante 10:39 7 IV Allegro ma non troppo 7:06 TT 78:39 3 COMPACT DISC TWO Sir Arthur Bliss (1891 – 1975) Concerto for Violin and Orchestra‡ 41:48 To Alfredo Campoli 1 I Allegro ma non troppo – Più animato – L’istesso tempo – Più agitato – Tempo I – Tranquillo – Più animato – Tempo I – Più animato – Molto tranquillo – Moderato – Tempo I – Più mosso – Animato 15:43 2 II Vivo – Tranquillo – Vivo – Meno mosso – Animando – Vivo 8:49 3 III Introduzione. Andante sostenuto – Allegro deciso in modo zingaro – Più mosso (scherzando) – Subito largamente – Cadenza – Andante molto tranquillo – Animato – Ancora più vivo 17:10 4 John Veale (1922 – 2006) Violin Concerto§ 35:38 4 I Moderato – Allegro – Tempo I – Allegro 15:55 5 II Lament. Largo 11:47 6 III Vivace – Andantino – Tempo I – Andantino – Tempo I – Andantino – Tempo I 7:53 TT 77:36 Lydia Mordkovitch violin London Philharmonic Orchestra* City of London Sinfonia† BBC National Orchestra of Wales‡ Lesley Hatfield leader BBC Symphony Orchestra§ Stephen Bryant leader Bryden Thomson* Richard Hickox†‡§ 5 British Violin Concertos Bax: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra on the manuscript testifies) but according Sir Arnold Bax’s (1883 – 1953) career as an to William Walton, Heifetz found the music orchestral composer started in 1905 with disappointing. -

Selected Vocal Repertoire

Selected Vocal Repertoire * = premiered by Barbara Hannigan van der Aa Here (to be found) * Here (in circles) * One * Abrahamsen let me tell you* Andriessen Four Beatles Songs Writing to Vermeer (Saskia) * Aperghis de la nature de la gravité de la nature de l’eau * Ayres In the Alps* J.S. Bach B minor mass Coffee Cantata (Lieschen) Hunt Cantata (Diana) Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen (Cantata 51) Johannes Passion Lutheran Mass Magnificat Matthäus Passion Peasant Cantata C.P.E. Bach Passion de Lezten Leidens Barry Karlheinz Stockhausen * La Plus Forte (Madame X) * The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (Gabrielle) The Importance of Being Earnest (Cecily Cardew) Beckwith Synthetic Trios Benjamin Written on Skin (Agnes)* Berg Der Wein Lulu (title role) Sieben Frühe Lieder Wozzeck fragments for soprano and orchestra Berio Sequenza 3 Sinfonia Binsbergen Sidenote: Howard Report* Boccherini Stabat Mater Boulez Le visage nuptial Pli selon pli Britten Les Illuminations The Rape of Lucretia (Lucia) Carissimi Jephtha (Jephtha’s daughter) Castiglione Cantus Planus Cavalli Giasone (Amore, Alinda) Charpentier Actéon (Arethuze) Chin Le silence des sirènes * Clerambault L’amour piqué par une abeille Crumb Apparition Dallapiccola Cinque frammenti di Saffo Debussy La Damoiselle Elue Defoort House of the Sleeping Beauties (The Women) * Dusapin Passion (Lei)* To God Dutilleux Correspondances Eötvös Octet Plus * Snatches of a Conversation Foss Time Cycle Francesconi Etymo Gluck Orfeo ed Eurydice (Amor) Grisey Quatre chants pour franchir le seuil Gubaidulina Hommage