Talking Trash: the Corporate Playbook of False Solutions to the Plastic Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amir, Abbas Review Palestinian Situation

QATAR | Page 4 SPORT | Page 1 Dreama Former F1 holds champion forum Niki Lauda for foster dies at 70 families published in QATAR since 1978 WEDNESDAY Vol. XXXX No. 11191 May 22, 2019 Ramadan 17, 1440 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Amir, Abbas review Palestinian situation His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani met with the Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas at the Amiri Diwan yesterday. During the meeting, they discussed the situation in Palestine, where Abbas briefed the Amir on the latest developments, and expressed sincere thanks to His Highness the Amir for Qatar’s steadfast support for the Palestinian cause and for its standing with the Palestinian people in facing the diff icult circumstances and challenges. The meeting was attended by a number of ministers and members of the off icial delegation accompanying the Palestinian president. His Highness the Amir hosted an Iftar banquet in honour of the Palestinian president and the delegation accompanying him at the Amiri Diwan. The banquet was attended by a number of ministers. In brief QATAR | Reaction Accreditation programme Qatar condemns armed New Trauma & Emergency attack in northeast India launched for cybersecurity Qatar has strongly condemned the armed attack which targeted Centre opens partially today audit service providers a convoy of vehicles in the state of Arunachal Pradesh in northeast QNA before being discharged. QNA Abdullah, stressed on the importance India, killing many people including Doha The new facility, which is located on Doha of working within the framework of the a local MP and injuring others. -

BIOGRAPHICAL DATA on SUSAN E. ARNOLD Vice Chair

(Photo by Ken Shung 2006) BIOGRAPHICAL DATA ON SUSAN E. ARNOLD Vice Chair – P&G Beauty & Health RESIDENCE: Cincinnati, Ohio, USA DATE OF BIRTH: March 8, 1954 PLACE: Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania EDUCATION: University of Pennsylvania, B.A., 1976 University of Pittsburgh, M.B.A., 1980 BUSINESS AFFILIATIONS PRIOR TO JOINING PROCTER & GAMBLE: None DATE JOINED PROCTER & GAMBLE: September 1980 POSITIONS HELD AND DATES: 1980 - Brand Assistant, Dawn/Ivory Snow 1981 - Sales Training, Philadelphia 1981 - Assistant Brand Manager, Oxydol 1983 - Assistant Brand Manager, Cascade 1984 - Brand Manager, Gain/Special Assignment 1985 - Brand Manager, Tide Sheets 1986 - Brand Manager, Dawn 1987 - Associate Advertising Manager, PS&D Advertising 1987 - Associate Advertising Manager, Laundry Products, PS&D Division 1988 - Associate Advertising Manager, Laundry Specialty Products, PS&D Division 1989 - Advertising Manager, Fabric Softeners, BS&HCP Division 1990 - Manager, Noxell Products, International Division (Canada) 1992 - Special Assignment to R. T. Blanchard 1993 - General Manager, Deodorants/Old Spice, Procter & Gamble USA 1996 - Vice President and General Manager, Deodorants/Old Spice and Skin Care Products-U.S., Procter & Gamble North America 1997 - Vice President and General Manager, Laundry Products-U.S., Procter & Gamble North America 1999 - Vice President-North America Fabric Care 1999 - President-Global Skin Care 2000 - President-Global Cosmetics & Skin Care 2000 - President-Global Personal Beauty Care 2002 - President-Global Personal Beauty Care & Global Feminine Care 2004 - Vice Chair – P&G Beauty 2006 - Vice Chair – P&G Beauty & Health SUSAN E. ARNOLD Vice Chair – P&G Beauty & Health The Procter & Gamble Company In 2004, Susan Arnold was the first woman to be named to the Vice Chair position at P&G. -

Notes from the Field

A U G U S T 2 0 1 9 | I S S U E 1 Notes from the Field Advocacy updates from the Planned Parenthood Central Coast Action Fund Policy State Budget Proposal Early this year, CA Governor Gavin Newsom proposed setting aside $100 million in the state budget to go toward reproductive health care services. Planned Parenthood staff and advocates across the state worked diligently to secure public and legislative support for this huge investment in the services reproductive health care providers with like Planned Parenthood offer throughout California. The proposal includes funding for Broad Comedy STI, HIV, and Hep C prevention and also ensures health providers have a seat at the table when discussing pharmacy benefits in SAT. SEPT 7. 2019 Medi-Cal. Central Coast advocates signed 718 postcards in support of Governor For more info or to purchase Newsom’s proposed budget throughout the past six months and on June 27th, our tickets visit: advocacy work paid off! California ppcentralcoastaf.org successfully secured $100 million for reproductive health care. Title X Title X On Thursday, July 11, an eleven-judge en banc panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit refused to block the Trump-Pence administration from enforcing the Title X Gag Rule, which bars Title X-funded family planning clinics Tfromi retferrlinge patien ts Xfor abortions. With the Title X gag rule slated to take effect, California Planned Parenthood health care centers have been forced to withdraw from the Title X program. The decision to withdraw from the program in California is specific to Planned Parenthood's mission and operational model. -

Vision Mission 2020 Annual Report

2020 VISION ANNUAL REPORT Every person enjoys full equality and dignity, the right to sexual health and autonomy, access to the best quality sexual health care available, and the ability to make informed decisions without coercion or discrimination. MISSION To improve health and well-being by providing high-quality, nonjudgmental sexual health care, honest and accurate sexuality education, and reproductive health and rights advocacy. PLANNEDPARENTHOOD.ORG/TENNESSEE President’s Board Chair’s Message Message For 80 years, Planned The pandemic has had a significant impact on our Parenthood of Tennessee affiliate and our patients, but thanks to your support, This past year, we have collectively weathered the most Now more than ever, there is so much at stake— and North Mississippi has been a place of care, we have kept our doors open for our patients, all while contentious presidential election in modern history equality, life, health, and dignity. It’s a profound time in compassion, information, healing, and health for tens taking care of our hardworking, brave, and dedicated and a nationwide uprising for racial justice, while we the fight for equitable reproductive and sexual health of thousands of people. staff. We’ve expanded telehealth opportunities for our watched the most deadly pandemic in modern history care access. Our current battles at the state and federal patients and grown our free long-acting birth control Every day in our health centers we see patients of all enter our homes, schools, and businesses— all in real levels mean that we cannot rest. But we will fight every and teen services statewide. -

2006 Annual Report Financial Highlights

2006 Annual Report Financial Highlights FINANCIAL SUMMARY (UNAUDITED) Amounts in millions, except per share amounts; Years ended June 30 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 Net Sales $68,222 $56,741 $51,407 $43,377 $40,238 Operating Income 13,249 10,469 9,382 7,312 6,073 Net Earnings 8,684 6,923 6,156 4,788 3,910 Net Earnings Margin 12.7% 12.2% 12.0% 11.0% 9.7% Basic Net Earnings Per Common Share $2.79 $ 2.70 $ 2.34 $ 1.80 $ 1.46 Diluted Net Earnings Per Common Share 2.64 2.53 2.20 1.70 1.39 Dividends Per Common Share 1.15 1.03 0.93 0.82 0.76 NET SALES OPERATING CASH FLOW DILUTED NET EARNINGS (in billions of dollars) (in billions of dollars) (per common share) 68.2 11.4 2.64 4 0 4 0 4 4 40 0 0 04 0 06 0 0 04 0 06 0 0 04 0 06 Contents Letter to Shareholders 2 Capability & Opportunity 7 P&G’s Billion-Dollar Brands 16 Financial Contents 21 Corporate Officers 64 Board of Directors 65 Shareholder Information 66 11-Year Financial Summary 67 P&GataGlance 68 P&G has built a strong foundation for consistent sustainable growth, with clear strategies and room to grow in each strategic focus area, core strengths in the competencies that matter most in our industry, and a unique organizational structure that leverages P&G strengths. We are focused on delivering a full decade of industry-leading top- and bottom-line growth. -

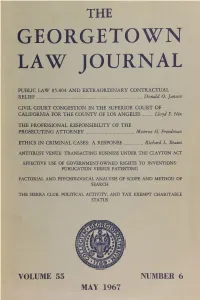

Georgetown Law Journal

THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL PUBLIC LAW 85-804 AND EXTRAORDINARY CONTRACTUAL RELIEF__________________________________________Donald O. Jansen CIVIL COURT CONGESTION IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF CALIFORNIA FOR THE COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES____Lloyd S. Nix THE PROFESSIONAL RESPONSIBILITY OF THE PROSECUTING ATTORNEY___________________ Monroe H. Freedman ETHICS IN CRIMINAL CASES: A RESPONSE_______ Richard L. Braun ANTITRUST VENUE: TRANSACTING BUSINESS UNDER THE CLAYTON ACT EFFECTIVE USE OF GOVERNMENT-OWNED RIGHTS TO INVENTIONS: PUBLICATION VERSUS PATENTING FACTORIAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF SCOPE AND METHOD OF SEARCH THE SIERRA CLUB, POLITICAL ACTIVITY, AND TAX EXEMPT CHARITABLE STATUS VOLUME 55 NUMBER 6 MAY 1967 THE BUREAU of NATIONAL AFFAIRS, inc. (BNA) cordially invites you to try the united states LAW WEEK for three months at half the regular rate! As an attorney, you know the in a special Summary and Analysis, a value of facts. That's why the five-minute review in which these legal following facts, regarding THE developments are tersely evaluated UNITED STATES LAW WEEK, for their effect on current law. should be particularly meaning ■ A key feature of LAW WEEK is its ful to you: high-speed reporting of Opinions of ■ The primary function of LAW WEEK the United States Supreme Court—in is to safeguard you against missing a full text, accompanied by crisp and single development of legal importance accurate summary digests. Mailed the . yet to save your time by greatly same day they are handed down, reducing your reading load! these exact photographic reproduc ■ To do this, LAW WEEK's expert tions of the Court's Opinions eliminate staff of lawyer-editors sifts thousands all possibility of error. -

Courier Gazette

Issued, Thursday Tuesday Thursday Issue Saturday T he Courier-Gazette Entered as Second Clan Mall Matte, Established January, 1846. By The Conrler-Uaxette, 465 Main St. Rockland, Maine, Thursday, July 27, 1939 TWELVE PAGES V olum e 94 Number 89. The Courier-Gazette He Rode The Goat Is Close At Hand [EDITORIAL] THREk-TIMKSA-WEEK NEARING ITS APEX “The Black Cat” Editor Lions Visit Hot Weather Gov. Barrows To Lead Pa WM O FULLER The near approach of August, universally recognized as the Associate Editor Initiation Upon Gow, rade In Rockport— Sw im ‘'big summer month" of the year, finds the Pentbscot Bay FRANK A WIN8LOW Whose Smile Slays ming Meet New Feature region well entrenched with visitors. The SamoseJ Hotel at Bubecrlptlona S3 00 ner year payable Rockland Breakwater, which might fairly be termed the sum lb advance; slnjlt coplea three cenite. | Rockland Lions admitted a new With Gov. Lewis O Barrows mer capital of this glorious region, has a very gratifying Advertlalnf rate* baaed upon clrcula-1 lion and very reasonable. member to their charmed circle yes leading the street parade at 6 p. m registry list, and the readers of Miss Pauline Ricker’s articles NEWSPAPER HISTORY terday and celebrated the event Aug. 2, the fourteenth annual will note that this beautiful and exclusive resort Is having a Tb» Rockland Oaaette waa estab- season of social activities unsurpassed for many years. The llah. d lu ,646 In 1874 the Courier was w th an Initiation de luxe. The Rockport Regatta Sportsmen's Show established and consolidated with the neighboring towns—Camden, Rcckport and Thomaston—all Uaeette In 1882 The Free Press was good-natured victim was George W will get underway. -

An Example of Open Innovation: P&G

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 195 ( 2015 ) 1496 – 1502 World Conference on Technology, Innovation and Entrepreneurship An Example of Open Innovation: P&G Nesli Nazik Ozkan* Istanbul University, Faculty of Economy, Istanbul Abstract Open innovation, also known as crowdsourcing or co-creation, is a way for companies to utilize the ideas and strength of the people outside their organization to make improvements in the internal processes or products. Many companies seek input from those people outside their organization for solving some of their trickiest problems. Open innovation help them to drive employee productivity, customer loyalty and better innovation. Open innovation process consists of three main steps. These are concept phase, development phase and implementation phase. In the concept phase, research activities are carried out. In the development phase, skills are defined and projects are developed. In the implementation phase projects are implemented and exchange of information is accelerated. P&G leads the companies who applied concept of open innovation successfully in the world. Procter & Gamble Co. as the world’s 40th biggest and 84th innovative company created the web site for this propose which is known Connect + Develop to encourage open innovation to help them to drive employee productivity. P&G's open innovation strategy has enabled to establish more than 2,000 successful agreements with innovation partners around the world. C+D already has delivered strategic value all across the company, and a series of game-changing consumer innovations. -

CANDY: Candy Bar $0.95 Altoids Peppermints $1.00 Breathsavers

Please use this list when ordering items from the Country Store, using the complete description (but not price). No more than 10 individual items can be ordered at one time – e.g. 3 candy bars count as 3 items. Call x2167 the night before you plan to pick up the items. Give your name, UNIT NUMBER, phone extension. Pick-up hours are 1 – 3 PM Monday – Saturday. CANDY: Candy Bar $0.95 Altoids peppermints $1.00 Breathsavers Peppermint $0.85 Breathsavers Spearmints $0.85 Cadbury Bar chocolate $1.95 Dentyne Peppermint gum $1.25 Dentyne Spearmint gum $1.25 Eclipse Polar Ice chewing gum $1.25 Fruit stripe chewing gum $1.25 Lifesavers Five Flavor $0.75 Lindt Lindor Dark chocolate $0.33 Lindt Lindor Milk chocolate $0.33 M&M Peanut chocolate $1.50 Mentos mints $1.00 Tic Tac Fresh Mints $0.95 Toblerone chocolate $2.19 Trident gum $1.25 Wrigley Big Red gum $1.25 Wrigley Juicy Fruit gum $1.25 SNACKS Almonds $3.00 Better Cheddars $3.90 Big Mama $1.28 Bud’s Best Wafers $0.55 Cheez-it $0.80 Chex Mix $0.66 Chips Ahoy $4.40 Chips, regular $1.25 Club crackers $1.80 Page 1 of 13 Fig Newtons $2.30 Gardetto snack mix $2.40 Ginger Snaps $5.08 Lorna Doone cookies $2.00 Nature Valley bar $0.48 Oreo cookies $2.30 Pea Snack Crisps $2.00 Pepperidge Farm cookies $3.89 Pepperidge Farm Goldfish $2.49 Planters, Peanut Pack $0.80 Planters Cashews, can $6.20 Planters cashews, pack $1.50 Planters cocktail peanuts, can $4.25 Planters mixed nuts, can $5.00 Planters unsalted nuts $4.50 Popcorn butter $0.80 Pretzels $1.25 Ritz cheese cracker sandwiches $0.50 Ritz crackers $4.30 -

Transformative Events in the LGBTQ Rights Movement

Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality Volume 5 Issue 2 Article 10 Spring 7-7-2017 Transformative Events in the LGBTQ Rights Movement Ellen A. Andersen University of Vermont, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijlse Part of the Law Commons Publication Citation Ellen Ann Andersen, Transformative Events in the LGBTQ Rights Movement, 5 Ind. J.L. & Soc. Equality 441 (2017). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transformative Events in the LGBTQ Rights Movement Ellen Ann Andersen* ABSTRACT Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 Supreme Court case holding that same-sex couples had a constitutional right to marry under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, was widely hailed in the media as a turning point for the LGBTQ rights movement. In this article, I contemplate the meaning of turning points. Social movement scholars have shown that specific events can, on rare occasion, alter the subsequent trajectory of a social movement. Such events have been termed ‘transformative events.’ I ask whether judicial decisions have the capacity to be transformative events and, if so, under what circumstances. I begin by developing a set of criteria for identifying a transformative event which I then apply to a handful of judicial decisions that, like Obergefell, have been described widely as turning points and/or watersheds in the struggle for LGBTQ rights. -

2.2.9. Procter & Gamble

1 Dirty recyclables of a Procter & Gamble brand Credit: Les Stone P&G has made no commitments regarding collection, and neither calls for legislation in this area nor mentions support for DRS. It high- lights different targets on its US environmental sustainability webpage6 than on its UK equivalent.7 At the time of writing, there was no reference to the development of reuse-and-refill delivery models for P&G products on their UK site;8 on its US site, however, the company highlights its 2019 participation in test programmes with TerraCycle’s Loop project in New York and Paris,9 in which its brands Pantene, Gillette and Venus were included.10 When it comes to reduction of virgin-plastic use, P&G states alternative materials will only be used ‘when it makes sense’, and that lightweighting, increasing recycled content and moving towards more concentrated products will take priority.11 However, this does not appear to involve an absolute reduction in the total number of single-use plastic-packaging units. It is also unclear what instances the company will consider using alternative materials in, and which types of materials. In another document on the company’s brand criteria for 2030, it states it will achieve ‘a meaningful increase in responsibly-sourced bio-based, or recycled or more resource efficient materi- als’;12 however, this commitment is nebulous because it does not include an actual target, timeframe or more detail on what ‘responsi- bly-sourced’ means. When it comes to minimum recycled content, P&G talks about ‘continuously innovating with recycled plastic’,13 and, according to As You Sow, has a recycled-content target of 8% for 2025.14 This is a very modest increase – from 6.3% in 2018. -

NARAL-WD2020-Digitaledition-1.Pdf

NARAL PRO-CHOICE AMERICA The United States ACCESS FACT: Currently, there are no states that provide total access Restricted Access The state of reproductive healthcare access in the United States is alarming. Due to the dearth of access in many regions, the nationwide status is “restricted access.” The meter’s colors represent the status of reproductive healthcare access in each state: a spectrum from bright red for “severely restricted access” to dark purple representing “total access.” As shown below, a handful of states have made great strides in expanding and protecting access to reproductive healthcare, achieving the status of “strongly protected access.” Yet, no state has achieved “total access” at this time. The majority of the states are in red, which should serve as a warning about the lack of reproductive healthcare access in much of the nation. An overview of the states that fall within each access category is below, and more detailed information about each state can be found in the state profiles. Colorado Minnesota Alaska Nevada Iowa New Hampshire Delaware New Jersey Massachusetts Rhode Island Maryland New Mexico SOME PROTECTED ACCESS ACCESS Florida California Montana Kansas STRONGLY Connecticut New York RESTRICTED Wyoming ACCESS PROTECTED Hawaii Oregon ACCESS Illinois Vermont Maine Washington SEVERELY TOTAL RESTRICTED ACCESS Alabama North Dakota ACCESS None Arizona Ohio Arkansas Oklahoma Georgia Pennsylvania Idaho South Carolina Indiana South Dakota Reproductive Healthcare Kentucky Tennessee Access Meter Louisiana Texas Michigan