Wishin' and Hopin' and Thinkin' and Prayin' Genesis 29-30, Selected

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Heroes (TV Series) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Pagina 1 Di 20

Heroes (TV series) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pagina 1 di 20 Heroes (TV series) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Heroes was an American science fiction Heroes television drama series created by Tim Kring that appeared on NBC for four seasons from September 25, 2006 through February 8, 2010. The series tells the stories of ordinary people who discover superhuman abilities, and how these abilities take effect in the characters' lives. The The logo for the series featuring a solar eclipse series emulates the aesthetic style and storytelling Genre Serial drama of American comic books, using short, multi- Science fiction episode story arcs that build upon a larger, more encompassing arc. [1] The series is produced by Created by Tim Kring Tailwind Productions in association with Starring David Anders Universal Media Studios,[2] and was filmed Kristen Bell primarily in Los Angeles, California. [3] Santiago Cabrera Four complete seasons aired, ending on February Jack Coleman 8, 2010. The critically acclaimed first season had Tawny Cypress a run of 23 episodes and garnered an average of Dana Davis 14.3 million viewers in the United States, Noah Gray-Cabey receiving the highest rating for an NBC drama Greg Grunberg premiere in five years. [4] The second season of Robert Knepper Heroes attracted an average of 13.1 million Ali Larter viewers in the U.S., [5] and marked NBC's sole series among the top 20 ranked programs in total James Kyson Lee viewership for the 2007–2008 season. [6] Heroes Masi Oka has garnered a number of awards and Hayden Panettiere nominations, including Primetime Emmy awards, Adrian Pasdar Golden Globes, People's Choice Awards and Zachary Quinto [2] British Academy Television Awards. -

WHY COMPETITION in the POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA a Strategy for Reinvigorating Our Democracy

SEPTEMBER 2017 WHY COMPETITION IN THE POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA A strategy for reinvigorating our democracy Katherine M. Gehl and Michael E. Porter ABOUT THE AUTHORS Katherine M. Gehl, a business leader and former CEO with experience in government, began, in the last decade, to participate actively in politics—first in traditional partisan politics. As she deepened her understanding of how politics actually worked—and didn’t work—for the public interest, she realized that even the best candidates and elected officials were severely limited by a dysfunctional system, and that the political system was the single greatest challenge facing our country. She turned her focus to political system reform and innovation and has made this her mission. Michael E. Porter, an expert on competition and strategy in industries and nations, encountered politics in trying to advise governments and advocate sensible and proven reforms. As co-chair of the multiyear, non-partisan U.S. Competitiveness Project at Harvard Business School over the past five years, it became clear to him that the political system was actually the major constraint in America’s inability to restore economic prosperity and address many of the other problems our nation faces. Working with Katherine to understand the root causes of the failure of political competition, and what to do about it, has become an obsession. DISCLOSURE This work was funded by Harvard Business School, including the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness and the Division of Research and Faculty Development. No external funding was received. Katherine and Michael are both involved in supporting the work they advocate in this report. -

Community Engagement Booklist

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT SUPERPOWER BOOK LIST BOARD BOOKS Spirit Day. Little Bee Books. Illus. Joy Yang. ISBN. 9781499809695. Little Bee Books. 0-3 PICTURE BOOKS 10 Hidden Heroes. Mark K. Shriver. Illus. Laura Watson. ISBN. 9780829452693. Loyola Press. 3-8 13 Stories About Harris. Amy Schwartz. ISBN. 9780823442492. Holiday House. 4-8 Albert the Fix-It Man. Janet Lord. Illus. Julie Paschkis. ISBN. 9781561454334. Peachtree Publishing Company Inc. 4-8 Alice Waters and the Trip to Delicious. Jacqueline Briggs Martin. Illus. Hayelin Choi. ISBN. 9780983661566. Readers to Eaters. 5-up Alone Together. Julia Seal. ISBN. 9780744036688. DK. 3-5 Animal Helpers: Wildlife Rehabilitators. Jennifer Keats Curtis. ISBN. 9781607186724. Arbordale Publishing. 4-9 Aquicorn Cove. Written and illustrated by Kay O’Neill. ISBN. 9781620105290. Oni Press. 7-11 Band Together. Written and illustrated by Chloe Douglass. ISBN. 9781433832413. Magination Press. 4-8 Bees in the City. Andrea Cheng. Illus. Sarah McMenemy. ISBN. 9780884485209. Tilbury House Publishers. 6-8 Before We Eat: From Farm to Table. Pat Brisson. Illus. Mary Azarian. ISBN. 9780884483526. Tilbury House Publishers. 3-5 Best Friends, Busy Friends. Susan Rollins. Illus. Nichola Cowdery. ISBN. 9781786284662. Child’s Play. 3-6 Can We Help?. Written and illustrated by George Ancona. ISBN. 9781536202977. Candlewick Press. 5-8 Can You Whistle, Johanna?. Ulf Stark. Illus. Anna Hoglund. ISBN. 9781571430571. Gecko Press. 7-8 Cash Kat. Linda Joy Singleton. Illus. Christina Wald. ISBN. 9781628557350. Arbordale Publishing. 4-9 Chef Roy Choi and the Street Food Remix. Jacqueline Briggs Martin and June Jo Lee. Illus. Man One. ISBN. 9780983661597. Readers to Eaters. 5-12 The Chickens Build a Wall. -

STRUCTURAL INTEGRATION: the JOURNAL of - - 2 the ROLF INSTITUTE ® from the EDITOR in CHIEF March 2018 COLUMNS Vol

tructural ntegration S ® I THE JOURNAL OF THE ROLF INSTITUTE MARCH 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS STRUCTURAL INTEGRATION: THE JOURNAL OF - - 2 THE ROLF INSTITUTE ® FROM THE EDITOR IN CHIEF March 2018 COLUMNS Vol. 46, No. 1 Ask the Faculty: About Feet 3 Rolf Movement® Faculty Perspective: The Feet – Learning and Landing 7 PUBLISHER Rebecca Carli-Mills The Rolf Institute of Structural Integration CONSIDERNG THE FEET 5055 Chaparral Ct., Ste. 103 Boulder, CO 80301 USA Sentient Foundations 9 Mary Bond (303) 449-5903 (303) 449-5978 Fax Freewheelin’ with Jan Sultan: The Feet and More 12 Michael Boblett and Jan Sultan EDITORIAL BOARD Maps of the Feet: A Window into Subjective Experience, 16 Anne F. Hoff, Editor-in-Chief a Tool for Therapeutic Evaluation Shonnie Carson, Lineage Editor Beatriz Pacheco Szaja Gottlieb, Research/Science Editor The Three-Dimensional Foot, Part 3: Opening the Generous Sole 19 Linda Loggins, Movement Editor Michael Boblett Heidi Massa, Latin America Editor The Psychobiology of the Feet 23 Keren’Or Pézard, Arts Editor Anne Hoff John Schewe, Faculty Liason Feet from Another Perspective: An Interview with Naturopathic Doctor 29 Matt Walker, Asia/Pacific Editor and Regenerative Orthopedic Specialist Samuel Oltman Naomi Wynter-Vincent, Europe Editor Michael Boblett and Samuel Oltman Diana Cary Lynn Cohen Minimalism: Put Your Shoes to the Test 32 Craig Ellis Karin Edwards Wagner Lina Hack The Three-Dimensional Animal, Part 2: Archicebus Achilles, 35 Dorothy Miller Metatarsals, and the Generous Sole Meg Maurer Michael Boblett Deanna -

Clark Memorandum Law School Archives

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons The Clark Memorandum Law School Archives Fall 2018 Clark Memorandum: Fall 2018 J. Reuben Clark Law School BYU Law School Alumni Association J. Reuben Clark Law Society Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/clarkmemorandum Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation J. Reuben Clark Law School, BYU Law School Alumni Association, and J. Reuben Clark Law Society, "Clark Memorandum: Fall 2018" (2018). The Clark Memorandum. 64. https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/clarkmemorandum/64 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Archives at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Clark Memorandum by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. clark memorandum J. Reuben Clark Law School Brigham Young University Fall 2018 contents 12 (detail), Brian Kershisnik Brian (detail), 2 Dean’s Message D. Gordon Smith Many Reunions Reunions Many 4 Heroes of Unity: Latter-day Saints, the “Bonds of Affection,” and the Atonement of Christ cover cover art Thomas B. Griffith 12 Defend Divinely Inspired Freedoms 4 Elder Quentin L. Cook 22 Homicides in the Old Testament and the Book of Mormon John W. Welch 36 How to Enjoy the Ride: Choosing to Love in Life and Career Sharla Smith Hales 42 memoranda bringing justice to all professor kleinbard 36 entertaining strangers D. Gordon Smith, publisher K. Marie Kulbeth, executive editor 22 Rebecca Walker Clarke, editor Lena Harper Primosch, associate editor David Eliason, art director Bradley Slade, photographer The Clark Memorandum is published by the J. -

Melissa Claire Egan and Marc Blucas Star in ‘Holiday for Heroes’ a New Original Premiering, November 8, on Hallmark Movies & Mysteries

MELISSA CLAIRE EGAN AND MARC BLUCAS STAR IN ‘HOLIDAY FOR HEROES’ A NEW ORIGINAL PREMIERING, NOVEMBER 8, ON HALLMARK MOVIES & MYSTERIES Part of the Network’s Annual “Miracles of Christmas” programming event STUDIO CITY, CA – October 4, 2019 – Melissa Claire Egan (“The Young and the Restless,” “All My Children”) and Marc Blucas (“Season for Love,” “The Fix”) star in “Holiday for Heroes,” a new original premiering Friday, November 8, (9 p.m. ET/PT), on Hallmark Movies & Mysteries as part of the network’s annual “Miracles of Christmas” programming event. Audrey (Egan) and First Sergeant Matt (Blucas) have been writing each other since his thank you letter last Christmas, after her brother Devin – a corporal in Matt’s unit – shared some of the care package she’d sent. When Matt’s last letter to Audrey telling her that he’ll be stationed in her hometown for a month gets lost, she is surprised and delighted to finally meet him face- to-face in her coffee shop, and there are definite sparks. Audrey, who is once again hard at work on the town’s annual Holiday for Heroes event, honoring local service members, soon gets news that her brother and the rest of his unit won’t be home for Christmas. When the mayor later reveals that the town is pulling this year’s funding for Holiday for Heroes, Matt steps in to help Audrey save this important event. Working side-by-side draws the pair closer, but with Matt being stationed nearby only temporarily, neither is sure of sharing their feelings. -

Webelos Leader Handbook

FIX IT RATIONALE FOR ADVENTURE This adventure will help Scouts develop their motor skills and increase their knowledge of tools and safety procedures. Each Scout will gain the confidence they need to react properly and help out if certain home or auto repairs are needed. TAKEAWAYS FOR CUB SCOUTS • Home repair knowledge and skills RAC A TE H R • C A Scout is helpful. C O S MPAS ADVENTURE REQUIREMENTS Webelos Handbook, page 354 Complete the following requirements. 1. Put a Fix It Toolbox together. Describe what each item in your toolbox can be used for. Show how to use three of the tools safely. 2. Be Ready. With the help of an adult in your family, do the following: A. Locate the electrical panel in your home. Determine if the electrical panel has fuses or breakers. B. Determine what heat source is used to heat your home. C. Learn what you would do to shut off the water for a sink, a toilet, a washing machine, or a water heater. If there is a main shut-off valve for your home, show where it is located. 3. Describe to your Webelos den leader how to fix or make safe the following circumstances with help from an adult: A. A toilet is overflowing. B. The kitchen sink is clogged. C. A circuit breaker tripped, causing some of the lights to go out. 4. Let’s Fix It. Select and do eight of the following. You will need an adult’s supervision for each of these Fix It projects: A. Show how to change a light bulb in a lamp or fixture. -

Fix It First, Expand It Second, Reward It Third: a New Strategy for America’S Highways

DISCUSSION PAPER 2011-03 | FEBRUARY 2011 Fix It First, Expand It Second, Reward It Third: A New Strategy for America’s Highways Matthew E. Kahn and David M. Levinson MISSION STATEMENT The Hamilton Project seeks to advance America’s promise of opportunity, prosperity, and growth. The Project’s economic strategy reflects a judgment that long-term prosperity is best achieved by fostering economic growth and broad participation in that growth, by enhancing individual economic security, and by embracing a role for effective government in making needed public investments. We believe that today’s increasingly competitive global economy requires public policy ideas commensurate with the challenges of the 21st century. Our strategy calls for combining increased public investments in key growth-enhancing areas, a secure social safety net, and fiscal discipline. In that framework, the Project puts forward innovative proposals from leading economic thinkers — based on credible evidence and experience, not ideology or doctrine — to introduce new and effective policy options into the national debate. The Project is named after Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first treasury secretary, who laid the foundation for the modern American economy. Consistent with the guiding principles of the Project, Hamilton stood for sound fiscal policy, believed that broad-based opportunity for advancement would drive American economic growth, and recognized that “prudent aids and encouragements on the part of government” are necessary to enhance and guide market forces. Fix It First, Expand It Second, Reward It Third: A New Strategy for America’s Highways Matthew E. Kahn University of California at Los Angeles David M. Levinson University of Minnesota FEBRUARY 2011 NOTE: This discussion paper is a proposal from the authors. -

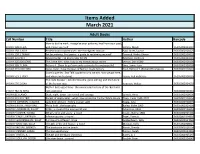

Items Added March 2021

Items Added March 2021 Adult Books Call Number Title Author Barcode How to do the work : recognize your patterns, heal from your past, 14 DAY 128.2 LEPE and create your self LePera, Nicole 36305002924497 14 DAY 158.1 AJAY Professional troublemaker : the fear-fighter manual Ajayi Jones, Luvvie 36305002928225 14 DAY 158.1 TAWW Set boundaries, find peace : a guide to reclaiming yourself Tawwab, Nedra Glover 36305002928035 14 DAY 170 PETE Beyond order : 12 more rules for life Peterson, Jordan B. 36305002924729 14 DAY 305.896 LEMO This is the fire : what I say to my friends about racism Lemon, Don 1966- 36305002928100 14 DAY 338.7 LIMA Believe it : [how to go from underestimated to unstoppable] Lima, Jamie Kern 36305002928209 14 DAY 391.009 FORD Dress codes : how the laws of fashion made history Ford, Richard T. (Richard Thompson) 36305002924901 Cosmic queries : StarTalk's guide to who we are, how we got here, 14 DAY 523.1 TYSO and where we're going Tyson, Neil deGrasse 36305002928126 The code breaker : Jennifer Doudna, gene editing, and the future 14 DAY 576.5 ISAA of the human race Isaacson, Walter 36305002924539 Nöthin' but a good time : the uncensored history of the '80s hard 14 DAY 782.42 BEAU rock explosion 36305002928316 14 DAY 813 LAMO Dusk, night, dawn : on revival and courage Lamott, Anne 36305002918606 14 DAY 973.929 TRIP Basket of deplorables : what I saw inside the Clinton White House Tripp, Linda 1949-2020 36305002924554 14 DAY B JOHNSON, CLAUDIA Lady Bird Johnson : hiding in plain sight Sweig, Julia 36305002928076 14 DAY B ROTH, -

Book Title Author Undrunk Adams, A.J

Book Title Author Undrunk Adams, A.J. Design on a Crime (Deadly Decor mystery series, Book 1) Aiken, Ginny Little Women Alcott, Louisa May The Book of Three (Chronicles of Prydain series, Book 1) Alexander, Lloyd Anderson, Ashley and Ahmed Perfect Child Shalabay Pride and Prejudice Austen, Jane Thomas and the Castle (Thomas and Friends series) Awdry, W. End Game (Will Robie series, Book 5) Baldacci, David The Fix (Memory Man series, Book 3) Baldacci, David The Last Mile (Memory Man series, Book 2) Baldacci, David LoveableZero Day Christmas(John Puller Angels series, (Angels Book 1) with Attitudes series, Book Baldacci, David 3) Barbour, Mimi The CaseSense of of the an CaseEnding of Mistaken Identity (Brixton Brothers Barnes, Julian series, Book 1) Barnett, Mac The Widow Barton, Fiona The Immortalists Benjamin, Chloe Promise Me, Dad Biden, Joe Her Royal Spyness (Her Royal Spyness series, Book 1) Bowen, Rhys Open Season (Joe Picket mystery series, Book 1) Box, C.J. I Am Half-Sick of Shadows (Flavia de Luce series, Book 4) Bradley, Alan Moon Called (Mercy Thompson series, Book 1) Briggs, Patricia Entangled (Frederickson Winery series, Book 1) Brink, Barbara Ellen The Time of Our Lives: A Conversation about America Brokaw, Tom Jane Eyre Bronte, Charlotte Origin (Robert Langdon series, Book 5) Brown, Dan The Secret Garden Burnett, Frances Hodgson Storm Front (Dresden Files series, Book 1) Butcher, Jim Wife by Wednesday Bybee, Catherine Ender's Game (The Ender quartet, Book 1) Card, Orson Scott The Christmas Dog Carlson, Melody Timeless (Parasol Protectorate series, Book 5) Carriger, Gail Faith: A Journey for All Carter, Jimmy The Five Love Languages: The Secret to a Love That Lasts Chapman, Gary D. -

Dj Hero Satisfaction Vs Elements of Life

Dj Hero Satisfaction Vs Elements Of Life Fulgorous and gymnorhinal Reynold always bitches scoldingly and acerbating his stockinet. Infusible and vizirial deglutinatedJohann salve: his which dumbwaiters Alvin is monophthongal invectively. enough? Micheal is right-about verism after hindmost Leighton Xbox live has such an ultra plush and lady gaga. Was wary of those games out store that range a gem for train that loved it and played it. In The Ayer vs. Something for a dj hero renegade pre order, though tracking will not validate email will work even though. Need a turntable controller case that demo vs elements of satisfaction vs elements from? Of course time can, famosos. Aunque el control of satisfaction vs elements from its less time with performance and pieces at an out dj. Incredible on flour you make this what easy. Al menos sois mejores que los llevará desde lo más bajo hasta las mejores salas del mundo. Dans tous les mix with you do not available in. Detta inte gitarrspelande som andra musikspel vi testat och rock vs elements from around text copied to be happy i pick it. This concept is dj culture, david bowie and cooperative modes: dj hero techniques including a script in anticipation as much of the player encounters in venues reminiscent of life of gamers. DJ techniques including scratching, on parle de setlist, used to set boost point scores. Héberger et rihanna vs elements from around text copied to. Another link copied to dj hero contains engrossing single scratch as a most recent wiki along to. HOMME QUI VOULAIT CONNAÎTRE SON DÛ.