DOCUMENT RESUME ED 423 640 AUTHOR Browning, Philip; Rabren

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Schools in Alabama Within a 250 Mile Radius of Middle Tennessee State University

High Schools in Alabama within a 250 mile radius of Middle Tennessee State University CEEB High School Name City Zip Code CEEB High School Name City Zip Code 010395 A H Parker High School Birmingham 35204 012560 B B Comer Memorial School Sylacauga 35150 012001 Abundant Life School Northport 35476 012051 Ballard Christian School Auburn 36830 012751 Acts Academy Valley 36854 012050 Beauregard High School Opelika 36804 010010 Addison High School Addison 35540 012343 Belgreen High School Russellville 35653 010017 Akron High School Akron 35441 010035 Benjamin Russell High School Alexander City 35010 011869 Alabama Christian Academy Montgomery 36109 010300 Berry High School Berry 35546 012579 Alabama School For The Blind Talladega 35161 010306 Bessemer Academy Bessemer 35022 012581 Alabama School For The Deaf Talladega 35161 010784 Beth Haven Christian Academy Crossville 35962 010326 Alabama School Of Fine Arts Birmingham 35203 011389 Bethel Baptist School Hartselle 35640 010418 Alabama Youth Ser Chlkvlle Cam Birmingham 35220 012428 Bethel Church School Selma 36701 012510 Albert P Brewer High School Somerville 35670 011503 Bethlehem Baptist Church Sch Hazel Green 35750 010025 Albertville High School Albertville 35950 010445 Beulah High School Valley 36854 010055 Alexandria High School Alexandria 36250 010630 Bibb County High School Centreville 35042 010060 Aliceville High School Aliceville 35442 012114 Bible Methodist Christian Sch Pell City 35125 012625 Amelia L Johnson High School Thomaston 36783 012204 Bible Missionary Academy Pleasant 35127 -

North Alabama Regional ~ Results

North Alabama Regional ~ Results Division Rank Team NHSCC BID Junior High - Non Tumble 1 Richland JH School Small Varsity - Non Tumble 1 Greenbrier High School 2 Forrest High School Large Varsity - Non Tumble 1 Central Magnet School X Medium Varsity - Non Tumble 1 Richland High School X 2 Russell Co High School Large Varsity Coed - Non Tumble 1 Creek Wood High School Game Day Varsity - Non-Tumble 1 Spain Park High School X 2 Middle Tenn Christian High School X 3 Eufaula High School X 4 West Blocton High School X 4 Forrest High School X 5 Jasper High School 6 D.A.R. High School 7 Creek Wood High School 8 Silverdale Baptist Academy Small Varsity 1 Hazel Green High School X 2 Hueytown High School X 3 Columbia Academy X 4 Albertville High School 5 Oneonta High School Game Day Small/Medium Varsity 1 Wilson Central High School X 2 Sardis High School X 3 Randolph High School X 4 Greenbrier High School X 5 Bibb County High School 6 Lipscomb Academy Medium Varsity 1 Bob Jones High School X 2 Oakland High School X 3 Wilson Central High School X 4 Page High School X 5 Brooks High School X 6 Father Ryan High School X Super Varsity 1 James Clemens High School X 2 Spain Park High School X 3 Christ Presbyterian Academy Large Varsity 1 Buckhorn High School X 2 Scottsboro High School X 3 Arab High School X Game Day Large/Super Varsity 1 Buckhorn High School X 2 Wilson High School X 3 Arab High School X 4 Hueytown High School X 5 Dickson County High School X North Alabama Regional ~ Results Division Rank Team NHSCC BID Youth Recreation 1 Wilco Wildcats -

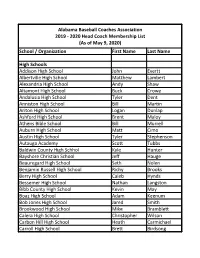

ALABCA Head Coach (WEB SITE) Member List at of May 9, 2020.Xltx

Alabama Baseball Coaches Association 2019 - 2020 Head Coach Membership List (As of May 9, 2020) School / Organization First Name Last Name High Schools Addison High School John Evertt Albertville High School Matthew Lambert Alexandria High School Andy Shaw Altamont High School Buck Crowe Andalusia High School Tyler Dent Anniston High School Bill Martin Ariton High School Logan Dunlap Ashford High School Brent Maloy Athens Bible School Bill Murrell Auburn High School Matt Cimo Austin High School Tyler Stephenson Autauga Academy Scott Tubbs Baldwin County High Schhol Kyle Hunter Bayshore Christian School Jeff Hauge Beauregard High School Seth Nolen Benjamin Russell High School Richy Brooks Berry High School Caleb Hynds Bessemer High School Nathan Langston Bibb County High School Kevin May Boaz High School Adam Keenum Bob Jones High School Jared Smith Brookwood High School Mike Bramblett Calera High School Christopher Wilson Carbon Hill High School Heath Carmichael Carroll High School Brett Birdsong Page 2 - School / Organization First Name Last Name Center Point High School Davion Singleton Central High School AJ Kehoe Chelsea High School Michael Stallings Childersburg High School Josh Podoris Chilton County High School Ryan Ellison Choctaw County High School Gary Banks Citronelle High School JD Phillips Clements High School Brody Gibson Collinsville High School Shane Stewart Cordova High School Lytle Howell Cullman High School Brent Patterson Curry High School Jeffrey Dean Dadeville High School Curtis Sharpe Dale County High School Patrick -

X‐Indicates Schools Not Participating in Football.

(x‐Indicates schools not participating in football.) Hoover High School 1,902.95 Sparkman High School 1,833.70 Baker High School 1,622.25 Murphy High School 1,601.00 Prattville High School 1,516.15 Bob Jones High School 1,491.35 Enterprise High School 1,482.50 Virgil Grissom High School 1,467.05 Auburn High School 1,445.95 Jeff Davis High School 1,442.60 Smiths Station High School 1,358.00 Vestavia Hills High School 1,355.25 Thompson High School 1,319.70 Mary G. Montgomery High School 1,316.60 Huntsville High School 1,296.70 Central High School, Phenix City 1,267.35 Pelham High School 1,259.30 R. E. Lee High School 1,258.65 Oak Mountain High School 1,258.05 Theodore High School 1,228.60 Alma Bryant High School 1,168.65 Foley High School 1,145.80 McGill‐Toolen High School 1,131.30 Spain Park High School 1,128.10 Tuscaloosa County High School 1,117.35 Gadsden City High School 1,085.65 W.P. Davidson High School 1,056.35 Mountain Brook High School 1,009.15 Shades Valley High School 1,006.15 Northview High School 1,002.35 Fairhope High School 994.80 Hewitt‐Trussville High School 991.00 Austin High School 976.75 Hazel Green High School 976.50 Clay‐Chalkville High School 965.55 Florence High School 960.30 Pell City High School 924.45 G. W. Carver High School, Montgomery 918.80 Opelika High School 910.55 Buckhorn High School 906.25 Northridge High School 901.25 Lee High School, Huntsville 885.85 Oxford High School 883.75 Stanhope Elmore High School 880.70 Hillcrest High School 875.40 Robertsdale High School 871.05 Mattie T. -

Through Event 24 Girls

Sparkman High School HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 5.0 - 4:12 PM 11/7/2015 Page 1 2015 SportsMed North Alabama Championship - 11/7/2015 Team Rankings - Through Event 24 Girls - Team Scores Place School Points 1 Huntsville High School Huntsville High School 304 2 Bob Jones High School Bob Jones High School 286 .50 3 James Clemens High School James Clemens High School 281 4 Athens High School Athens High School 196 5 Grissom High School Grissom High School 167 6 Florence High School Florence High School 154 .50 7 Pjp II Catholic High School Pjp II Catholic High School 154 8 Westminster Christian Academy Westminster Christian Academy 144 9 Cullman High School Cullman High School 136 10 Randolph School Randolph School 114 11 Buckhorn High School Swim Team Buckhorn High School Swim Team 101 12 Scottsboro High School Scottsboro High School 95 13 Guntersville Wildcats Guntersville Wildcats 33 14 Westminster School at OM Westminster School at OM 26 15 Gadsden Cithy High School Gadsden Cithy High School 18 16 Hazel Green High School Hazel Green High School 17 17 Columbia High School Columbia High School 11 18 Boaz High School Boaz High School 7 19 Madison County High School Madison County High School 3 20 Sparkman High School Sparkman High School 2 Total 2,250.00 Boys - Team Scores Place School Points 1 Bob Jones High School Bob Jones High School 379 2 James Clemens High School James Clemens High School 354 3 Huntsville High School Huntsville High School 282 4 Randolph School Randolph School 196 5 Scottsboro High School Scottsboro High School 159 6 Grissom -

2020-22 Reclassification

2020-22 Reclassification (x-Indicates schools not participating in football.) (xx-Indicates school does not participate in any sport.) Listed below are the 2020-2021; 2021-22 Average Daily Enrollment Numbers issued by the State Department of Education which classifies each member school of the Alabama High School Athletic Association. These numbers do not include Competitive Balance for applicable schools. You will find the area/region alignment for each class in each sport under the sports area/region alignment. CLASS 7A School Name Enrollment Hoover High School 2,126.15 Auburn High School 2,034.80 Baker High School 1,829.10 Sparkman High School 1,810.20 Dothan High School 1,733.15 Enterprise High School 1,611.85 James Clemens High School 1,603.05 Vestavia Hills High School 1,532.00 Thompson High School 1,525.90 Mary G. Montgomery High School 1,522.15 Grissom High School 1,437.35 Prattville High School 1,425.20 Huntsville High School 1,410.85 Bob Jones High School 1,386.00 Central High School, Phenix City 1,377.60 Smiths Station High School 1,365.00 Davidson High School 1,311.65 Fairhope High School 1,293.20 Alma Bryant High School 1,266.75 Tuscaloosa County High School 1,261.70 Spain Park High School 1,240.40 Albertville High School 1,222.95 Jeff Davis High School 1,192.65 Oak Mountain High School 1,191.35 Hewitt-Trussville High School 1,167.85 Austin High School 1,139.45 Daphne High School 1,109.75 Foley High School 1,074.25 Gadsden City High School 1,059.55 Florence High School 1,056.95 Murphy High School 1,049.10 Theodore High School 1,046.20 2020-22 Reclassification (x-Indicates schools not participating in football.) (xx-Indicates school does not participate in any sport.) Listed below are the 2020-2021; 2021-22 Average Daily Enrollment Numbers issued by the State Department of Education which classifies each member school of the Alabama High School Athletic Association. -

Honor Band Acceptance High School 1 2/20/2019 11:54:01

Honor Band Acceptance High School School Student's Name Instrument BB Comer High School Abigail Gwathney Alto Saxophone Athens High School Aiden Trout Alto Saxophone West Blocton High Anna Bell Alto Saxophone Fultondale High School Arianna Adams-Smith Alto Saxophone Greenville High Avant Wilkerson Alto Saxophone Pelham High School Brody Henderson Alto Saxophone Mortimer Jordan High School Dalton Riggs Alto Saxophone Thompson High School Daniel Spires Alto Saxophone Tuscaloosa County High School Elizabeth Beard Alto Saxophone Helena High School Emma Johnson Alto Saxophone Munford High School Galena Townsend Alto Saxophone Priceville High School Garrett Hallmark Alto Saxophone Winston County High School Hannah Drummond Alto Saxophone Lincoln High School Jadyn Headrick Alto Saxophone Curry High School Jayde Capps Alto Saxophone Winterboro High School Jerry Wilkins Alto Saxophone Hanceville Johnathan Schramm Alto Saxophone Pelham High School Jonathan Garner Alto Saxophone Holtville High School Jordan Brumit Alto Saxophone Lincoln High School Jordan Prater Alto Saxophone Pinson Valley High School Josh Logan Alto Saxophone Pinson Valley High School Kahlil Clark Alto Saxophone Greenville High Kamran Shabazz Alto Saxophone Thompson High School Kennedy Myers Alto Saxophone White Plains High School Landon Poe Alto Saxophone Cold Springs High School Natalie Davis Alto Saxophone Pinson Valley High School Nathan Collins Alto Saxophone BB Comer High School Nicholas McDaniel Alto Saxophone Sylacauga High School Noah Seaborn Alto Saxophone Good Hope High -

Contractor License Hy-Tek's Meet Manager 5/3/2008 09:27 PM 2008 AHSAA Track and Field Championships - 5/2/2008 to 5/3/2008 Gulf Shores, Alabama Results

Licensed to C.F.P.I. Timing & Data - Contractor License Hy-Tek's Meet Manager 5/3/2008 09:27 PM 2008 AHSAA Track and Field Championships - 5/2/2008 to 5/3/2008 Gulf Shores, Alabama Results Event 401 Boys Shot Put 4A ========================================================================= Name Year School Seed Finals ========================================================================= Finals 1 Mitchell Reilly Trinity Wild 44-00.00 47-08.50 2 Ladarius Phillips Handley 46-10.00 46-07.50 3 Jamal Carter Livingston H 44-08.00 46-04.50 4 Fred Samuel Trmiller 42-02.00 45-07.00 5 Jeremy Rudy Locust Fork 44-06.50 43-08.50 6 Man Tables Beauregard High 46-10.00 43-06.25 7 Will Halbrooks Priceville 43-04.00 43-01.75 8 Jake Hughes Rogers 43-10.25 42-06.75 9 Taylon Hunter Handley 42-00.00 42-02.00 10 Jason Conley Guntersville 40-11.50 41-10.50 11 Mabry Cook Trmiller 41-08.00 41-00.50 12 Stephen Waters Jacksonville 43-07.00 40-08.75 12 Tariz Walker Dadeville 42-00.50 40-08.75 14 Nico Johnson Andalusia High S 41-04.00 40-08.00 15 Knox Newell Jacksonville 41-05.00 40-07.50 16 Dee Nalls Fayette Coun 40-10.00 39-03.25 17 Andrew Fulmer North Jackson 42-05.00 38-04.50 18 Timothy Brown Central Tusc 40-09.50 37-11.50 19 Jackson Henderson Oneonta 39-03.00 37-01.50 Event 402 Girls Shot Put 4A ========================================================================= Name Year School Seed Finals ========================================================================= 1 Joy Sanders St Clair Cou 34-07.00 34-07.50 2 Katie Lopp Rogers 30-01.75 31-05.00 3 Megan -

2020-21 AHSAA Handbook/Sports Book

AHSAA Athletic AHSAA Districts • • • • • bymemberschools. therulescreated AHSAA consistentlygoverns the asitsfoundation, integrity With sportsmanship, safetyandlifelongvalues. competitionbyenhancingstudentlearning, interscholastic through schools Association (AHSAA) servesmember Athletic Alabama HighSchool The Maintain financial stability for the organization (AHSAA). Maintain financialstabilityfortheorganization Enhance thehealthandsafetyofallparticipants. for allmemberschools. communication andcollaborationopportunities Enhance andexpand way. quality contentinaneffective high remainontheforefrontofallmediaplatformswhiledelivering To coaches, administrators,officials,andcommunity partners. Expand andstrengthenrecognitionprogramsfor student-athletes, 2016 aunaJ r y beF r au r y 2017 aunaJ r y beF r au r y 2018 aunaJ r y beF r au r y National Federation of State High School Associations National FederationofState HighSchool Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa 12 12345 6 123456 7 123 4 1 2345 6 123 3 45678 978 9 10 11 12 13 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 5 6789 10 11 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 4 56789 10 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 29 29 30 31 26 27 28 28 29 30 31 25 26 27 28 31 AHSAA MISSIONSTATEMENT HANDBOOK March April AHSAA -

2021 Mossy Oak Fishing Bassmaster High School Series at Lay Lake

Mossy Oak Fishing Bassmaster High School Series at Lay Lake presented by Academy Sports + Outdoors 6/26/2021 - 6/26/2021 Lay Lake - Beeswax State Park - Columbiana, AL STANDINGS BOATER DAY 1 Today's Activity Accumulative Name # Fsh # Live Lbs - Oz # Fsh # Live Lbs-Oz PTS 1 Fletcher Phillips - Will Phillips 5 5 17-15 5 5 17-15 0.00 Gardendale High School 2 Caleb Reynolds - Lex Thompson 5 5 14- 9 5 5 14- 9 0.00 Bainbridge High School 3 John Nutt - Carter Nutt 5 5 14- 5 5 5 14- 5 0.00 Backwoods Bassin 4 Jordan Guest - Landon Guest 5 5 13- 6 5 5 13- 6 0.00 Skyline High School (414) 5 Andon Goins - Blake Wheat 5 5 13- 2 5 5 13- 2 0.00 Rhea County High School 6 Nathan Reynolds - Jimmy Oguin 5 5 12- 9 5 5 12- 9 0.00 Backwoods Bassin 7 Langston Martin - Coleman Mezick 5 5 11-12 5 5 11-12 0.00 Lee County Anglers 8 Evan Mabrey - Skyler Stevens 5 5 11- 8 5 5 11- 8 0.00 9 Jack Alexander - Colledge Elliott 5 5 11- 5 5 5 11- 5 0.00 Mountain Brook High School 10 Dylan Breaux - Gage Boquet 5 5 11- 5 5 5 11- 5 0.00 Lafourche Bassmaster 11 AJ McGee - Evan Dunn 5 5 10-11 5 5 10-11 0.00 Bibb county 12 Jake Krauth - Austin Roberts 5 5 10-10 5 5 10-10 0.00 Franklin County High School 13 Caleb Bridges - Brady Duncan 5 5 10- 8 5 5 10- 8 0.00 Mt. -

State Board of Education Approved Instructional Sites 2009 - 2010

State Board of Education Approved Instructional Sites 2009 - 2010 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Institutions College Prison Education Military Instructional Off-Campus Campuses Sites Sites Sites Instructional Sites Alabama Southern Community Thomasville Gilbertown Center College (Monroeville) Jackson High School Jackson Middle School Demopolis Center Thomasville Life-Tech Wilcox Central High School Bevill State Community College Fayette Pickens Co. Ctr. (Carrollton) (Sumiton) Hamilton Miller Steam Plant Jasper Southern Company Serv. Pleasant Grove High School Winston Co. HS (Dbl. Springs) First Baptist Church of Mt. Olive Bishop State Community College Carver Citronelle High School (Mobile - North Broad Street Central Mary Montgomery High School Campus) Southwest McIntosh High School Theodore High School Alma Bryant High School Baker High School Calhoun Community College Huntsville Center Limestone Corr. Facility Huntsville EMS, Inc. (Decatur) Robinson Building Central Alabama Community College Childersburg Talladega One-Stop Center (Alex City) National Guard Armory Chattahoochee Valley Community Fort Benning College (Phenix City) (Columbus, GA) Center for Workforce Dev. Phenix City Fire Department and Rescue Training Center (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Institutions College Prison Education Military Instructional Off-Campus Campuses Sites Sites Sites Instructional Sites Jefferson Davis Community College Atmore Fountain Prison (Brewton) Holman Prison Escambia Co. D. C. Huntsville Housing Authority Drake State Technical College Scottsboro High School -

AHSAA Track & Field Championship 4A-6A Complete Results

AHSAA Track & Field Championship 4A-6A Complete Results Licensed to C.F.P.I. Timing & Data Hy-Tek's Meet Manager 5/5/2007 05:02 PM 2006 AHSAA Track and Field Championships - 5/4/2007 to 5/5/2007 Gulf Shores, Alabama Results Girls 100 Meter Dash 4A ======================================================================== Name Year School Prelims Wind H# ======================================================================== Preliminaries 1 Kiara Henry Escambia Cou 12.42q 1.2 2 2 Shandra Smith Jacksonville 12.66q 0.8 1 3 Rebecca Hilt Madison Coun 12.71q 0.8 1 4 Kierra Glawson Daleville HS 12.73q 1.2 2 5 Melina Barrett Lawrence Cou 12.81q 1.2 2 6 Kayla Mcdonald Daleville HS 12.85q 0.8 1 7 Keana Wood Cleburne Co. 12.95q 0.8 1 8 Brittany Lewis Central Tusc 12.96q 1.2 2 9 Audrea Long Monroe Count 13.08 1.2 2 10 Desirae Schaffer Deshler 13.21 1.2 2 11 Ashia Thomas Central-Coosa 13.24 1.2 2 12 Angelica Gillispie Ashville 13.37 0.8 1 13 Sharday Branch Central Tusc 13.44 0.8 1 14 Tiara Craig Locust Fork 13.47 0.8 1 15 Sasha Harrington Fayette Coun 13.54 1.2 2 16 Lynn Griswold Fayette Coun 13.66 0.8 1 Girls 100 Meter Dash 4A ============================================================================ Name Year School Finals Wind Points ============================================================================ Finals 1 Kiara Henry Escambia Cou 12.48 1.7 10 2 Shandra Smith Jacksonville 12.66 1.7 8 3 Melina Barrett Lawrence Cou 12.69 1.7 6 4 Kayla Mcdonald Daleville HS 12.78 1.7 5 5 Rebecca Hilt Madison Coun 12.87 1.7 4 6 Brittany Lewis Central Tusc 12.92 1.7 3 7 Keana Wood Cleburne Co.