A History of Aboriginal Programming at Carleton University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Nunavut, Canada

english cover 11/14/01 1:13 PM Page 1 FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove Principal Researchers: Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Nunavut Wildlife Management Board Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove PO Box 1379 Principal Researchers: Iqaluit, Nunavut Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and X0A 0H0 Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike Cover photo: Glenn Williams/Ursus Illustration on cover, inside of cover, title page, dedication page, and used as a report motif: “Arvanniaqtut (Whale Hunters)”, sc 1986, Simeonie Kopapik, Cape Dorset Print Collection. ©Nunavut Wildlife Management Board March, 2000 Table of Contents I LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES . .i II DEDICATION . .ii III ABSTRACT . .iii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 RATIONALE AND BACKGROUND FOR THE STUDY . .1 1.2 TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND SCIENCE . .1 2 METHODOLOGY 3 2.1 PLANNING AND DESIGN . .3 2.2 THE STUDY AREA . .4 2.3 INTERVIEW TECHNIQUES AND THE QUESTIONNAIRE . .4 2.4 METHODS OF DATA ANALYSIS . -

26727 Consignor Auction Catalogue Template

Auction of Important Canadian & International Art September 24, 2020 AUCTION OF IMPORTANT CANADIAN & INTERNATIONAL ART LIVE AUCTION THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 24TH AT 7:00 PM ROYAL ONTARIO MUSEUM 100 Queen’s Park (Queen’s Park at Bloor Street) Toronto, Ontario ON VIEW Please note: Viewings will be by appointment. Please contact our team or visit our website to arrange a viewing. COWLEY ABBOTT GALLERY 326 Dundas Street West, Toronto, Ontario JULY 8TH - SEPTEMBER 4TH Monday to Friday: 9:00 am to 5:00 pm SEPTEMBER 8TH - 24TH Monday to Friday: 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Saturdays: 11:00 am to 5:00 pm Sunday, September 20th: 11:00 am to 5:00 pm 326 Dundas Street West (across the street from the Art Gallery of Ontario) Toronto, Ontario M5T 1G5 416-479-9703 | 1-866-931-8415 (toll free) | [email protected] 2 COWLEY ABBOTT | September Auction 2020 Cowley Abbott Fine Art was founded as Consignor Canadian Fine Art in August 2013 as an innovative partnership within the Canadian Art industry between Rob Cowley, Lydia Abbott and Ryan Mayberry. In response to the changing landscape of the Canadian art market and art collecting practices, the frm acts to bridge the services of a retail gallery and auction business, specializing in consultation, valuation and professional presentation of Canadian art. Cowley Abbott has rapidly grown to be a leader in today’s competitive Canadian auction industry, holding semi-annual live auctions, as well as monthly online Canadian and International art auctions. Our frm also ofers services for private sales, charity auctions and formal appraisal services, including insurance, probate and donation. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 Published by Strategic Planning and Government Relations P.O

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 Published by Strategic Planning and Government Relations P.O. Box 6100, Station Centre-ville Montreal, Quebec H3C 3H5 Internet: onf-nfb.gc.ca/en E-mail: [email protected] Cover page: ANGRY INUK, Alethea Arnaquq-Baril © 2017 National Film Board of Canada ISBN 0-7722-1278-3 2nd Quarter 2017 Printed in Canada TABLE OF CONTENTS 2016–2017 IN NUMBERS MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNMENT FILM COMMISSIONER FOREWORD HIGHLIGHTS 1. THE NFB: A CENTRE FOR CREATIVITY AND EXCELLENCE 2. INCLUSION 3. WORKS THAT REACH EVER LARGER AUDIENCES, RAISE QUESTIONS AND ENGAGE 4. AN ORGANIZATION FOCUSED ON THE FUTURE AWARDS AND HONOURS GOVERNANCE MANAGEMENT SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES IN 2016–2017 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ANNEX I: THE NFB ACROSS CANADA ANNEX II: PRODUCTIONS ANNEX III: INDEPENDENT FILM PROJECTS SUPPORTED BY ACIC AND FAP AS THE CROW FLIES Tess Girard August 1, 2017 The Honourable Mélanie Joly Minister of Canadian Heritage Ottawa, Ontario Minister: I have the honour of submitting to you, in accordance with the provisions of section 20(1) of the National Film Act, the Annual Report of the National Film Board of Canada for the period ended March 31, 2017. The report also provides highlights of noteworthy events of this fiscal year. Yours respectfully, Claude Joli-Coeur Government Film Commissioner and Chairperson of the National Film Board of Canada ANTHEM Image from Canada 150 video 6 | 2016-2017 2016–2017 IN NUMBERS 1 VIRTUAL REALITY WORK 2 INSTALLATIONS 2 INTERACTIVE WEBSITES 67 ORIGINAL FILMS AND CO-PRODUCTIONS 74 INDEPENDENT FILM PROJECTS -

THE ONTARIO CURRICULUM, GRADES 9 to 12 | First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies

2019 REVISED The Ontario Curriculum Grades 9 to 12 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies The Ontario Public Service endeavours to demonstrate leadership with respect to accessibility in Ontario. Our goal is to ensure that Ontario government services, products, and facilities are accessible to all our employees and to all members of the public we serve. This document, or the information that it contains, is available, on request, in alternative formats. Please forward all requests for alternative formats to ServiceOntario at 1-800-668-9938 (TTY: 1-800-268-7095). CONTENTS PREFACE 3 Secondary Schools for the Twenty-first Century � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �3 Supporting Students’ Well-being and Ability to Learn � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �3 INTRODUCTION 6 Vision and Goals of the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies Curriculum � � � � � � � � � � � � � �6 The Importance of the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies Curriculum � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �7 Citizenship Education in the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies Curriculum � � � � � � � �10 Roles and Responsibilities in the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies Program � � � � � � �12 THE PROGRAM IN FIRST NATIONS, MÉTIS, AND INUIT STUDIES 16 Overview of the Program � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �16 Curriculum Expectations � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

Ayapaahipiihk Naahkouhk

ILAJ YEARS/ANS parkscanada.gc.ca / parcscanada.gc.ca AYAPAAHIPIIHK NAAHKOUHK RESILIENCE RESISTANCE LU PORTRAY DU MICHIF MÉTIS ART l880 - 2011 Parks Parcs Canada Canada Canada RESILIENCE / RESISTANCE MÉTIS ART, 1880 - 2011 kc adams • jason baerg • maria beacham and eleanor beacham folster • christi belcourt bob boyer • marie grant breland • scott duffee - rosalie favell -Julie flett - Stephen foster david garneau • danis goulet • david hannan • rosalie laplante laroque - jim logan Caroline monnet • tannis nielsen • adeline pelletier dit racette • edward poitras • rick rivet BATOCHE NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE PARKS CANADA June 21 - September 15, 2011 Curated by: Sherry Farrell Racette BOB BOYER Dance of Life, Dance of Death, 1992 oil and acrylic on blanket, rawhide permanent collection of the Saskatchewan Arts Board RESILIENCE / RESISTANCE: METIS ART, 1880-2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 4 Aypaashpiihk, Naashkouhk: Lii Portray dii Michif 1880 - 2011 5 Curator's Statement 7 kcadams 8 jason baerg 9 maria beacham and eleanor beacham folster 10 christi belcourt 11 bob boyer 12 marie grant breland 13 scott duffee 14 rosaliefavell 15 Julie flett 16 Stephen foster 17 david garneau 18 danis goulet 19 david hannan 20 rosalie laplante laroque 21 jim logan 22 Caroline monnet 23 tannis nielsen 24 adeline pelletier dit racette 25 edward poitras 26 rick rivet 27 Notes 28 Works in the Exhibition 30 Credits 32 3 Resilience/Resistance gallery installation shot FOREWORD Batoche National Historic Site of Canada is proud to host RESILIENCE / RESISTANCE: MÉTIS ART, 1880-2011, the first Metis- specific exhibition since 1985. Funded by the Government of Canada, this is one of eighteen projects designed to help Métis com munities preserve and celebrate their history and culture as well as present their rich heritage to all Canadians. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 45/Thursday, March 7, 2019/Rules and Regulations

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 45 / Thursday, March 7, 2019 / Rules and Regulations 8263 III. Statutory and Executive Orders state submission in response to a ACTION: Final rule; issuance of Letters of Federal standard. Authorization (LOA). Under Executive Order 12866 (58 FR This action does not impose an 51735, October 4, 1993), this action is information collection burden under the SUMMARY: NMFS, upon request from the not a ‘‘significant regulatory action’’ and provisions of the Paperwork Reduction National Park Service (NPS), hereby therefore is not subject to review under Act of 1995 (44 U.S.C. 3501 et seq.). issues regulations to govern the Executive Orders 12866 and 13563 (76 Burden is defined at 5 CFR 1320.3(b). unintentional taking of marine FR 3821, January 21, 2011). This action mammals incidental to research and is also not subject to Executive Order List of Subjects in 40 CFR Part 62 monitoring activities in southern Alaska 13211, ‘‘Actions Concerning Regulations Environmental protection, Air over the course of five years (2019– That Significantly Affect Energy Supply, pollution control, Administrative 2024). These regulations, which allow Distribution, or Use’’ (66 FR 28355, May practice and procedure, sewage sludge for the issuance of Letters of 22, 2001). This action approves the incineration units. Authorization (LOA) for the incidental state’s negative declaration as meeting Dated: March 1, 2019. take of marine mammals during the described activities and specified Federal requirements and imposes no James Gulliford, -

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism by Matthew Purvis A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020, Matthew Purvis i Abstract This dissertation concerns the relation between eroticism and nationalism in the work of a set of English Canadian artists in the mid-1960s-70s, namely John Boyle, Greg Curnoe, and Joyce Wieland. It contends that within their bodies of work there are ways of imagining nationalism and eroticism that are often formally or conceptually interrelated, either by strategy or figuration, and at times indistinguishable. This was evident in the content of their work, in the models that they established for interpreting it and present in more and less overt forms in some of the ways of imagining an English Canadian nationalism that surrounded them. The dissertation contextualizes the three artists in the terms of erotic art prevalent in the twentieth century and makes a case for them as part of a uniquely Canadian mode of decadence. Constructing my case largely from the published and unpublished writing of the three subjects and how these played against their reception, I have attempted to elaborate their artistic models and processes, as well as their understandings of eroticism and nationalism, situating them within the discourses on English Canadian nationalism and its potentially morbid prospects. Rather than treating this as a primarily cultural or socio-political issue, it is treated as both an epistemic and formal one. -

News Release. Tiff Unveils Top Ten Canadian Films of 2017

December 6, 2017 .NEWS RELEASE. TIFF UNVEILS TOP TEN CANADIAN FILMS OF 2017 The Canada’s Top Ten Film Festival™ illuminates the nation with public screenings, free events, and special guests Alanis Obomsawin, Evan Rachel Wood and Jeremy Podeswa TORONTO — TIFF® is toasting the end of Canada’s sesquicentennial with its compelling list of 2017’s best Canadian films for the 17th annual Canada’s Top Ten Film Festival™. Established in 2001, the festival is one of the largest and longest-running showcases of Canadian film. From January 12 to 21, 2018 at TIFF Bell Lightbox in Toronto, the 10-day event boasts a rich offering of public screenings, Q&A sessions and a special Industry Forum, followed by a nationwide tour stopping in Vancouver, Montreal, Regina, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Ottawa and Saskatoon. Cameron Bailey, Artistic Director of TIFF, says the Canada’s Top Ten Film Festival is a vibrant celebration of diversity and excellence in contemporary Canadian cinema. “Our filmmakers have proven that they are among the best in the world and all Canadians should feel incredibly proud to get behind them and celebrate their achievements. Wrapping up Canada’s year in the global spotlight, we are thrilled to present this uniquely Canadian list, rich not only in talent but also in its diversity of perspectives, stories, and voices that reflect our nation’s multiculturalism," said Bailey. Steve Gravestock, TIFF Senior Programmer, says the number of exciting new voices alongside seasoned masters in this year’s lineup is a testament to the health of the Canadian film industry. "With a top ten that includes five first- or second-time feature directors, there is much to celebrate in Canadian cinema this year," said Gravestock. -

In-Person Screening

THE NFB FILM CLUB FALL/WINTER 2020–2021 CONTACT Florence François, Programming Agent 514-914-9253 | [email protected] JOIN THE CLUB! The NFB Film Club gives public libraries the opportunity to offer their patrons free screenings of films from the NFB’s rich collection. In each Film Club program, you’ll find films for both adults and children: new releases exploring hot topics, timely and thought-provoking documentaries, award-winning animation, and a few timeless classics as well. The NFB Film Club offers free memberships to all Canadian public libraries. ORGANIZING A SCREENING STEP 3 Organize your advertising for the event—promote IN YOUR LIBRARY the screening(s) in your networks. (To organize a virtual screening, STEP 4 please refer to our online program.) Prior to your event, test the film format that was delivered to you (digitally or by mail) using your equipment (you have two weeks to download your STEP 1 film(s) from the day you receive the link). Decide which film(s) you’re interested in from the available titles, which can be found by clicking on the NFB Film Club page. STEP 2 Send your selection(s) by e-mail to [email protected] and include your screening date(s), time(s), and location(s), as well as the film format required for your venue. We can supply an electronic file (MP3, MOV) or can ship a physical copy. PROMOTIONAL MATERIALS ATTENDANCE FIGURES To help you promote your screenings, you’ll To assist us in tracking the outreach of the NFB’s also have access to our media space and all films, please make note of the number of people archived promotional materials (photos, posters, who attended each library or virtual screening. -

MURAL TRIBUTE to ALANIS OBOMSAWIN MU INAUGURATES a 20Th MURAL DEDICATED to MONTREAL’S GREAT ARTISTS

PRESS RELEASE UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL NOVEMBER 5TH 2018, 11 AM MURAL TRIBUTE TO ALANIS OBOMSAWIN MU INAUGURATES A 20th MURAL DEDICATED TO MONTREAL’S GREAT ARTISTS Montreal, November 5th, 2018 — MU, the charitable non-profit mural arts organization, inaugurated a new mural in the Ville-Marie borough paying tribute the great Abenaki filmmaker, Alanis Obomsawin. This new mural art piece is the 20th of MU’s collection Montreal’s Great Artists, an ambitious undertaking that has been a source of pride for the organization since 2010, highlighting the creative minds and forces of those who have made outstanding contributions to Montreal’s cultural scene. As part of this collection, MU was inaugurating, a year ago, a tribute to another Montreal great artist with the already iconic mural of Leonard Cohen overlooking downtown Montreal. The event took place in presence of Mrs Marie-Josée Parent, associate councillor in charge of culture and reconciliation for the City of Montreal; Mr Claude Joli-Cœur, Government Film Commissioner and Chairperson for the NFB; Mrs Alanis Obomsawin and the artist, Meky Ottawa. Also present were Ghislain Picard, Assembly of First nations Regional Chief and Richard O’Bomsawin, Chief of Odanak. The mural is located on Lincoln Avenue corner of Atwater, in the heart of the Peter-McGill district, where Mrs. Obomsawin has been living for more than fifty years. This mural is MU’s fourth mural celebrating the heritage of Indigenous Peoples in Montreal. Meky Ottawa, an emerging Atikamekw artist, was chosen to design the piece in homage to Alanis Obomsawin following a call for nominations dedicated to Indigenous artists. -

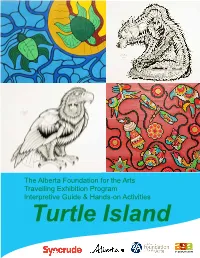

Turtle Island Education Guide

The Alberta Foundation for the Arts Travelling Exhibition Program Interpretive Guide & Hands-on Activities Turtle Island The Alberta Foundation for the Arts Travelling Exhibition Program The Interpretive Guide The Art Gallery of Alberta is pleased to present your community with a selection from its Travelling Exhibition Program. This is one of several exhibitions distributed by The Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the Alberta Foundation for the Arts Travelling Exhibition Program. This Interpretive Guide has been specifically designed to complement the exhibition you are now hosting. The suggested topics for discussion and accompanying activities can act as a guide to increase your viewers’ enjoyment and to assist you in developing programs to complement the exhibition. Questions and activities have been included at both elementary and advanced levels for younger and older visitors. At the Elementary School Level the Alberta Art Curriculum includes four components to provide students with a variety of experiences. These are: Reflection: Responses to visual forms in nature, designed objects and artworks Depiction: Development of imagery based on notions of realism Composition: Organization of images and their qualities in the creation of visual art Expression: Use of art materials as a vehicle for expressing statements The Secondary Level focuses on three major components of visual learning. These are: Drawings: Examining the ways we record visual information and discoveries Encounters: Meeting and responding to visual imagery Composition: Analyzing the ways images are put together to create meaning The activities in the Interpretive Guide address one or more of the above components and are generally suited for adaptation to a range of grade levels. -

1 Pocahontas No More: Indigenous Women Standing up for Each Other

1 Pocahontas No More: Indigenous Women Standing Up for Each Other in Twenty-First Century Cinema Sophie Mayer, Independent Scholar Abstract: Sydney Freeland’s fiction feature Drunktown’s Finest (2014) represents the return of Indigenous women’s feature filmmaking after a hiatus caused by neoconservative politics post-9/11. In the two decades since Disney’s Pocahontas (1995), filmmakers such as Valerie Red-Horse have challenged erasure and appropriation, but without coherent distribution or scholarship. Indigenous film festivals and settler state funding have led to a reestablishment, creating a cohort that includes Drunktown’s Finest. Repudiating both the figure of Pocahontas, as analysed by Elise M. Marubbio, and the erasure of Indigenous women in the new Western genre described by Susan Faludi, Drunktown’s Finest relates to both the work of white ally filmmakers of the early 2000s, such as Niki Caro, and to the work of contemporary Indigenous filmmakers working in both features (Marie-Hélène Cousineau and Madeline Ivalu of Arnait) and shorts (Danis Goulet, Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers). Foregrounding female agency, the film is framed by a traditional puberty ceremony that—through the presence of Felixia, a transgender/nádleeh woman—is configured as non-essentialist. The ceremony alters the temporality of the film, and inscribes a powerful new figure for Indigenous futures in the form of a young woman, in line with contemporary Indigenous online activism, and with the historical figure of Pocahontas. A young, brown-skinned, dark-haired woman is framed against a landscape—the land to which she belongs. Her traditional, cream-coloured clothes and jewellery move with the movement of her body against the wind; brilliant washes of colour change with the changing light.