Electronic Communications Privacy Act Committee On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vi--•·R~N ,: Ugib ,1@ F'o-R· A~I Pt1 1Hiiotl ·Unl.Er YA ;I.-Egcli.:L, M.2Im

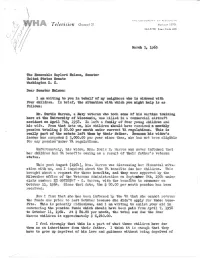

T H E Uf\JI\/EF-~SITY' o~=- WI S CONSir--.J Television Channel 21 Madison 53706 262-2720 Area Code 608 ch, 165 9le ~• Gqlont Jfelaoa, ._.tor Vlllldltatea leaw ~J.C. Dear----~ lelRBt I • wrlUna to ,n la N1111f ot IQ' -'pllora .. b 1d.4ow4 wttll tov eldl4ra. In vi•t• Qe dtaU. ld.tla vlaia ,_ ldpt Ml,p ta u toll.Ona •• Ollnta ~ N w, veteran who toC>. e train ng MN at .. llalftlWl."1' ot Wi.,e.onai , -w,· s lle ,1re ft uoi._.. • AJdl 111a, 9;.-v. l e · ' :f'amily · ft) w:-an · d hia •, • ~ that .fl-e on, b s c · U d?'en ·al Ul ?:mv _..,. pe s Olll totallt . 80aa00 pe . nth under C'Ut'rent v; re !bl• 18 naJ.11' part of 1M ••• left ._ w •t.r •--• incom~ hes tJ-_:{/:'.'~ad~d $ 3,000 .. .00 p,e:::· y~fl.'J:' ,since· th~n, she il'lcJG not b \3evi--•·r~n ,: Ugib ,1@ f'o-r· a~i pt1 1Hiiotl ·unl.er YA ;i.-egcli.:l, M.2im,. lfJ11;?01!' 1;~.. iir.ia 'tie:lJr, !J.:i•g wid.011~;; b1I"'~~ - Dc:>.- 1 s;, }~. 1-7ti~~~1-.:e-r1 ~:16, l~t.' 'V :.: '}..'1 t n.:fttt,n,:,;.d t tlo.. t he ·," 1::hlli:'l.r-~n tic..cd VA b€nei'i'tr.:.l r,,ert.d.n~ e,.cs a r\;:)sul t of theii: .fe.tb.;g:' s vet,iran. status,. Thl, ,3 p••Jrt, l\ 1.tg"iltt (1964 J, }-kf.L, 'tL 1~r':.'i/1 "'N'3.E:, t1ise'.:t5Gj.ng h ~:;" '.'.'l n~n~i~ll si t ,:1 at:t:01~ vti th ID·!~·~ ~L}n-d I :t.~1qu·~1~t1 i~ O";J'LJ~ t!'rc; ¥1!_ b(~U~fitz q:1u~ 2::!€\ ~:} c'!1_ild..~ •1t::1?Ja T:t1itJ 't)l'"(Ii:,&:l!.t ~o'.';;~'i;, @! I:>t~ c,r.. -

Union Calendar No. 481 104Th Congress, 2D Session – – – – – – – – – – – – House Report 104–879

1 Union Calendar No. 481 104th Congress, 2d Session ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± House Report 104±879 REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES DURING THE ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS PURSUANT TO CLAUSE 1(d) RULE XI OF THE RULES OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES JANUARY 2, 1997.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 36±501 WASHINGTON : 1997 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois, Chairman 1 CARLOS J. MOORHEAD, California JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., PATRICIA SCHROEDER, Colorado Wisconsin BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts BILL MCCOLLUM, Florida CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York GEORGE W. GEKAS, Pennsylvania HOWARD L. BERMAN, California HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina RICH BOUCHER, Virginia LAMAR SMITH, Texas JOHN BRYANT, Texas STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico JACK REED, Rhode Island ELTON GALLEGLY, California JERROLD NADLER, New York CHARLES T. CANADY, Florida ROBERT C. SCOTT, Virginia BOB INGLIS, South Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia XAVIER BECERRA, California STEPHEN E. BUYER, Indiana JOSEÂ E. SERRANO, New York 2 MARTIN R. HOKE, Ohio ZOE LOFGREN, California SONNY BONO, California SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas FRED HEINEMAN, North Carolina MAXINE WATERS, California 3 ED BRYANT, Tennessee STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MICHAEL PATRICK FLANAGAN, Illinois BOB BARR, Georgia ALAN F. COFFEY, JR., General Counsel/Staff Director JULIAN EPSTEIN, Minority Staff Director 1 Henry J. Hyde, Illinois, elected to the Committee as Chairman pursuant to House Resolution 11, approved by the House January 5 (legislative day of January 4), 1995. -

2012 Election Preview: the Projected Impact on Congressional Committees

2012 Election Preview: the Projected Impact on Congressional Committees K&L Gates LLP 1601 K Street Washington, DC 20006 +1.202.778.9000 October 2012 Table of Contents Table of Contents 1-2 Introduction 3 House Key Code 4 House Committee on Administration 5 House Committee on Agriculture 6 House Committee on Appropriations 7 House Committee on Armed Services 8 House Committee on the Budget 9 House Committee on Education and the Workforce 10 House Committee on Energy and Commerce 11 House Committee on Ethics 12 House Committee on Financial Services 13 House Committee on Foreign Affairs 14 House Committee on Homeland Security 15 House Committee on the Judiciary 16 House Committee on Natural Resources 17 House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform 18 House Committee on Rules 19 House Committee on Science, Space and Technology 20 House Committee on Small Business 21 House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure 22 House Committee on Veterans' Affairs 23 House Committee on Ways and Means 24 House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence 25 © 2012 K&L Gates LLP Page 1 Senate Key Code 26 Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry 27 Senate Committee on Appropriations 28 Senate Committee on Armed Services 29 Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs 30 Senate Committee on the Budget 31 Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation 32 Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources 33 Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works 34 Senate Committee on Finance 35 Senate Committee on Foreign -

How to Read the Bill History Page Hb 2480

HOW TO READ THE BILL HISTORY PAGE This tutorial will show you how to read the bill information and history page for a bill. This page and the next show the bill history for HB 2480 from the 2007-08 legislative session as it appears on the webpage. Beginning on page 3 this bill history is shown with a detailed explanation of what each line means. HB 2480 - 2007-08 (What is this?) Concerning public transportation fares. Sponsors: Clibborn, McIntire, Simpson Companion Bill: SB 6353 Go to documents. Go to videos. Bill History 2008 REGULAR SESSION Dec 21 Prefiled for introduction. Jan 14 First reading, referred to Transportation. (View Original Bill) Jan 17 Public hearing in the House Committee on Transportation at 3:30 PM. Jan 29 Executive action taken in the House Committee on Transportation at 3:30 PM. TR - Executive action taken by committee. TR - Majority; 1st substitute bill be substituted, do pass. (View 1st Substitute) Minority; do not pass. Feb 1 Passed to Rules Committee for second reading. Feb 12 Made eligible to be placed on second reading. Feb 13 Placed on second reading. Feb 14 1st substitute bill substituted (TR 08). (View 1st Substitute) Floor amendment(s) adopted. Rules suspended. Placed on Third Reading. Third reading, passed; yeas, 84; nays, 10; absent, 0; excused, 4. (View Roll Calls) (View 1st Engrossed) IN THE SENATE Feb 16 First reading, referred to Transportation. Feb 20 Public hearing in the Senate Committee on Transportation at 1:30 PM. Feb 26 Executive action taken in the Senate Committee on Transportation at 3:30 PM. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. March 10

1776 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. MARcH 10, H. Owen and ofW. W. Welch-severally to the Committee on Wax braces some six or seven hundred miles of road under one control, Claims. and, talring it in connection with its control of the Georgia road, By Mr. A.. HERR SMITH: The petition of soldiers and sailors of more than that. That is all worked in connection with the expor the late war for an increase of pension to all pensioners who lost an tation of productions at Savannah. The Louisville and Nashville arm and leg while in the line of duty-to the Committee on Invalid system, which is very prominent and controls probably some two Pensions. thousand miles of road, or more, works in harmony with the Central. By Mr. STONE: The petition of Patrick McDonald, to be placed That combination of roads naturally looks to Savannah as an outlet on the retired list-to the Committee on Military Affairs. for a great deal of the produce that is shipped over its lines. There By Mr. TALBOTT: Papers relating to the claim of Alexander M. is then the line by way of'the Georgia and Cent.ral, through Atlanta Templeton-to the Committee on War Claims. over the Stat.e Road~ as it is called, by the Nashville, Chattanoo~a By Mr. URNER: Papers relating to the claim of Robertson Topp antl Saint Louis, al o connecting with the Louisville and Nashviue and William L. Vance-to the same committee. Road to the western cities. There are the same connections up to By Mr. -

Congressional Record—Senate S10191

October 1, 2008 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S10191 are confident we will be able to restore by the House of Representatives under If you look at this map—I will leave the circulatory system, if you will, and the leadership of HOWARD BERMAN, the it up for a good part of the day—you regain health for the economy—the chairman of the Foreign Affairs Com- will appreciate, aside from the agree- body, if you will—and get the problem mittee of that body. ment itself, the strategic importance fixed for the American people. I have a letter from the Secretary of of this relation for the United States. I said yesterday that we are going to State, as well as other supporting in- India has become a major actor in fix this problem this week. The Senate formation, that leads us to the conclu- the world, and it increasingly sees will speak tonight. We will send to the sion that this bill ought to be passed, itself in concert with other global pow- House a package that, if passed, will and passed, I hope, overwhelmingly by ers, rather than in opposition to them. address the issue. this body because of the message it Indian Prime Minister Singh, who We will have demonstrated to the would send not only to the people and visited Washington just last week, has American people that we can deal with the Government of India but others as devoted energy and political courage in the crisis in the most difficult of well about the direction we intend to forging this agreement, and in seeking times—right before an election, when take in the 21st century about this approval for it in India. -

Congressional Directory NORTH CAROLINA

192 Congressional Directory NORTH CAROLINA NORTH CAROLINA (Population 2010, 9,535,483) SENATORS RICHARD BURR, Republican, of Winston-Salem, NC; born in Charlottesville, VA, November 30, 1955; education: R.J. Reynolds High School, Winston-Salem, NC, 1974; B.A., communications, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, 1978; professional: sales man- ager, Carswell Distributing; member: Reynolds Rotary Club; board member, Brenner Children’s Hospital; public service: U.S. House of Representatives, 1995–2005; served as vice-chairman of the Energy and Commerce Committee; married: Brooke Fauth, 1984; children: two sons; committees: ranking member, Veterans’ Affairs; Finance; Health, Education, Labor, and Pen- sions; Select Committee on Intelligence; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 2, 2004; re- elected to the U.S. Senate on November 2, 2010. Office Listings http://burr.senate.gov 217 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 .................................... (202) 224–3154 Chief of Staff.—Chris Joyner. FAX: 228–2981 Legislative Director.—Natasha Hickman. 2000 West First Street, Suite 508, Winston-Salem, NC 27104 .................................. (336) 631–5125 State Director.—Dean Myers. 100 Coast Line Street, Room 210, Rocky Mount, NC 27804 .................................... (252) 977–9522 201 North Front Street, Suite 809, Wilmington, NC 28401 ....................................... (910) 251–1058 *** KAY R. HAGAN, Democrat, of Greensboro, NC; born in Shelby, NC, May 26, 1953; edu- cation: B.A., Florida State University, 1975; J.D., Wake Forest University School of Law, 1978; professional: attorney and vice president of the Estate and Trust Division, NCNB, 1978–88; public service: North Carolina State Senator, 1999–2009; religion: Presbyterian; married: Chip Hagan; children: two daughters, one son; committees: Armed Services; Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs; Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions; Small Business and Entrepreneurship; elected to the U.S. -

Bills of Attainder

University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship Winter 2016 Bills of Attainder Matthew Steilen University at Buffalo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles Part of the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Matthew Steilen, Bills of Attainder, 53 Hous. L. Rev. 767 (2016). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/123 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE BILLS OF ATTAINDER Matthew Steilen* ABSTRACT What are bills of attainder? The traditional view is that bills of attainder are legislation that punishes an individual without judicial process. The Bill of Attainder Clause in Article I, Section 9 prohibits the Congress from passing such bills. But what about the President? The traditional view would seem to rule out application of the Clause to the President (acting without Congress) and to executive agencies, since neither passes bills. This Article aims to bring historical evidence to bear on the question of the scope of the Bill of Attainder Clause. The argument of the Article is that bills of attainder are best understood as a summary form of legal process, rather than a legislative act. This argument is based on a detailed historical reconstruction of English and early American practices, beginning with a study of the medieval Parliament rolls, year books, and other late medieval English texts, and early modern parliamentary diaries and journals covering the attainders of Elizabeth Barton under Henry VIII and Thomas Wentworth, earl of Strafford, under Charles I. -

The Beginner's Handbook of Amateur Radio

FM_Laster 9/25/01 12:46 PM Page i THE BEGINNER’S HANDBOOK OF AMATEUR RADIO This page intentionally left blank. FM_Laster 9/25/01 12:46 PM Page iii THE BEGINNER’S HANDBOOK OF AMATEUR RADIO Clay Laster, W5ZPV FOURTH EDITION McGraw-Hill New York San Francisco Washington, D.C. Auckland Bogotá Caracas Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan Montreal New Delhi San Juan Singapore Sydney Tokyo Toronto McGraw-Hill abc Copyright © 2001 by The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as per- mitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-139550-4 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-136187-1. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trade- marked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringe- ment of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. -

IATSE and Labor Movement News

FIRST QUARTER, 2012 NUMBER 635 FEATURES Report of the 10 General Executive Board January 30 - February 3, 2012, Atlanta, Georgia Work Connects Us All AFL-CIO Launches New 77 Campaign, New Website New IATSE-PAC Contest 79 for the “Stand up, Fight Back” Campaign INTERNATIONAL ALLIANCE OF THEATRICAL STAGE EMPLOYEES, MOVING PICTURE TECHNICIANS, ARTISTS AND ALLIED CRAFTS OF THE UNITED STATES, ITS TERRITORIES AND CANADA, AFL-CIO, CLC EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Matthew D. Loeb James B. Wood International President General Secretary–Treasurer Thomas C. Short Michael W. Proscia International General Secretary– President Emeritus Treasurer Emeritus Edward C. Powell International Vice President Emeritus Timothy F. Magee Brian J. Lawlor 1st Vice President 7th Vice President 900 Pallister Ave. 1430 Broadway, 20th Floor Detroit, MI 48202 New York, NY 10018 DEPARTMENTS Michael Barnes Michael F. Miller, Jr. 2nd Vice President 8th Vice President 2401 South Swanson Street 10045 Riverside Drive Philadelphia, PA 19148 Toluca Lake, CA 91602 4 President’s 74 Local News & Views J. Walter Cahill John T. Beckman, Jr. 3rd Vice President 9th Vice President Newsletter 5010 Rugby Avenue 1611 S. Broadway, #110 80 On Location Bethesda, MD 20814 St Louis, MO 63104 Thom Davis Daniel DiTolla 5 General Secretary- 4th Vice President 10th Vice President 2520 West Olive Avenue 1430 Broadway, 20th Floor Treasurer’s Message 82 Safety Zone Burbank, CA 91505 New York, NY 10018 Anthony M. DePaulo John Ford 5th Vice President 11th Vice President 6 IATSE and Labor 83 On the Show Floor 1430 Broadway, 20th Floor 326 West 48th Street New York, NY 10018 New York, NY 10036 Movement News Damian Petti John M. -

Bell Telephone Magazine

»y{iiuiiLviiitiJjitAi.¥A^»yj|tiAt^^ p?fsiJ i »^'iiy{i Hound / \T—^^, n ••J Period icsl Hansiasf Cttp public Hibrarp This Volume is for 5j I REFERENCE USE ONLY I From the collection of the ^ m o PreTinger a V IjJJibrary San Francisco, California 2008 I '. .':>;•.' '•, '•,.L:'',;j •', • .v, ;; Index to tne;i:'A ";.""' ;•;'!!••.'.•' Bell Telephone Magazine Volume XXVI, 1947 Information Department AMERICAN TELEPHONE AND TELEGRAPH COMPANY New York 7, N. Y. PRINTKD IN U. S. A. — BELL TELEPHONE MAGAZINE VOLUME XXVI, 1947 TABLE OF CONTENTS SPRING, 1947 The Teacher, by A. M . Sullivan 3 A Tribute to Alexander Graham Bell, by Walter S. Gifford 4 Mr. Bell and Bell Laboratories, by Oliver E. Buckley 6 Two Men and a Piece of Wire and faith 12 The Pioneers and the First Pioneer 21 The Bell Centennial in the Press 25 Helen Keller and Dr. Bell 29 The First Twenty-Five Years, by The Editors 30 America Is Calling, by IVilliani G. Thompson 35 Preparing Histories of the Telephone Business, by Samuel T. Gushing 52 Preparing a History of the Telephone in Connecticut, by Edward M. Folev, Jr 56 Who's Who & What's What 67 SUMMER, 1947 The Responsibility of Managcincnt in the r^)e!I System, by Walter S. Gifford .'. 70 Helping Customers Improve Telephone Usage Habits, by Justin E. Hoy 72 Employees Enjoy more than 70 Out-of-hour Activities, by /()/;// (/. Simmons *^I Keeping Our Automotive Equipment Modern. l)y Temf^le G. Smith 90 Mark Twain and the Telephone 100 0"^ Crossed Wireless ^ Twenty-five Years Ago in the Bell Telephone Quarterly 105 Who's Who & What's What 107 3 i3(J5'MT' SEP 1 5 1949 BELL TELEPHONE MAGAZINE INDEX. -

Letter from Stephen Johnson to Governor Schwarzenegger Denying

UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY WASHINGTON, D.C. 20460 DEC 1 9 2007 OFFICE OF THE ADMINISTRATOR The Honorable Arnold Schwarzenegger Governor of the State of California State Capitol Sacramento, California 95814 Dear Governor Schwarzenegger, As I have committed to you in previous correspondence, I am writing to inform you of my decision with respect to the request for a waiver of Federal preemption for motor vehicle greenhouse gas emission standards submitted by the California Air Resources Board (CARB). As you know, EPA undertook an extensive public notice and comment process with regard to the waiver request. The Agency held two public hearings: one on May 22, 2007 in Washington, D.C. and one in Sacramento, California on May 30, 2007. We heard from over 80 individuals at these hearings and received thousands of written comments during the ensuing public comment process from parties representing a broad set of interests, including state and local governments, public health and environmental organizations, academia, industry and citizens. The Agency also received and considered a substantial amount of technical and scientific material submitted after the close of the comment deadline on June 15, 2007. EPA has considered and granted previous waivers to California for standards covering pollutants that predominantly affect local and regional air quality. In contrast, the current waiver request for greenhouse gases is far different; it presents numerous issues that are distinguishable from all prior waiver requests. Unlike other air pollutants covered by previous waivers, greenhouse gases are fundamentally global in nature. Greenhouse gases contribute to the problem of global climate change, a problem that poses challenges for the entire nation and indeed the world.