Judge Joseph W. Woodrough August 29, 1873 - October 2, 1977

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record-Senate. J Anuary 18

/ 814 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. J ANUARY 18, SENATE. of the country; which were referred to the Committee on Agri culture and Forestry. M o NDAY, J anuary 18, 190./j.. He also presented petitions of the Woman's Home Missionary Prayer by the Chaplain, Rev. EnwARD EVERETT HALE. Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church of Cincinnati, Ohio; Mr. H. D. 1\Io ... rnY, a Senator from the State of Mississippi, ap of the congregation of the Methodist Episcopal Church of Mor -peared in his seat to-day. ristown; of sundry citizens of Poland; of the congregation of the The Secretary proceeded to read the J on.rnal of the proceedings First Congregational Church of Jamestown; of sundry citizens of of Friday last, when, on request of Mr. LoDGE, and by unanimous Brooklyn; of the congregation of theNorth Pl·esbyterian Church, consent, the further reading was dispensed with. of Binghampton; of the congregation of the First Swedish Bap The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The Journal will stand ap tist Church of Jamestown, and of the Woman's Missionary Soci proved. ety of Avon, all in the State of New York, praying for an inves RENTAL OF BUILDINGS. tigation of the charges made and filed against Ron. REED S:MOOT, The PRESIDENT pro tempore laid before the Senate a com a Senator from the State of Utah; which were referred to the Com munication from the Secretary of-Commerce and Labor, trans mittee on Privileges and Elections. mitting, in response to a resolution of the 17th ultimo, a state Mr. QUARLES presented a petition of the Board of Directors ment showing the quarters and buildings rented by the Depart of the Merchants and Manufacturers' Association of Milwaukee, ment of Commerce and Labor in the District of Columbia and Wis., praying for the enactment of legislation providing for the the various States and Territories; which, with the accompany reorganization of the consular se1·vice; which was referred to the ing paper, was referred to the Committee on Public Buildings Committee on Foreign Relations. -

Reed, Joseph R.Tif

Standard Form For Members of the LeQ l Slature Name of Representative Sena tor {1c .l, ~flu (i.v -1jz4 N ~vitl ?Jv /u~r~ a r~·/l:-..;, .&,-ti1:~ a .. / ~~LA--v-, ~ / .. ~ T-~v 1. Birthday and place 12 /'JuN 1£35 j,/".r/r.l<t-:., . · . f5::t?.t · .(~~ ~ > ~ , I ;:../'{ Vf' • i I ~ 1¥t5 ~t ,,; (h,"-7. 'X~ ! ..:ta. /;j !3 ~,. 7 r-¢7•rzr./ 3. Significant events for example: · A. Business W;, ;1£; / :£-d . ~~/ &.-~/--t p./,£l..'i 9 B. civic res pons ib il it iu t!J.t. /• ,{:..,.I ,~ LJ/ ;,. ./ 1J111~ov (. I ., ;V. I - ' 4. Church membership ______~~ A~~~~~.h~· F~.t~r~·A~,,~&~b~· ------------------------- 1tf -1.( /; - 5. Sessions served // / 2 ,,'A!'k a.../ /?(1.' ~~-"' I .-/!I.J>.A!L/'.o.M~., It~' 6. Public Offices 7 . 8. 9. Names of /r<·r.· ., · Source: Iowa Territorial and State Legislators Collection compiled by volunteers and staff at the State Historical Society of Iowa Library, Des Moines, Iowa. '. 12. Other applicable information ,{J,p.../4 ,~-1 - _$ f•- ,• u f. ofc>.,v 47" zZ- ,,.;., !~S2 .t ~7. aftfZ£.-A; I 'AA. c..,,.~.... ~-M t , / -~·Jr;'!h' _,,;A:!. ?Ji,Jit 'I vt!"/).,1.,. /~ Source: Iowa Territorial and State Legislators Collection compiled by volunteers and staff at the State Historical Society of Iowa Library, Des Moines, Iowa. sources Log For Legisl at ion Bntri es Applicability Source Applicable Information obtained I 'f'l/ . Source: Iowa Territorial and State Legislators Collection compiled by volunteers and staff at the State Historical Society of Iowa Library, Des Moines, Iowa. - ... - .. .. - -.. - -- ··---· ---·.-· ---. ··.-- ·-- - --·- --- ~-- - --·-·- -- ----·---------·- Source: Iowa Territorial and State Legislators Collection compiled by volunteers and staff at the State Historical Society of Iowa Library, Des Moines, Iowa. -

Protecting Holmes' Notes Through the Conditional Sales Acts

Digital Commons at St. Mary's University Faculty Articles School of Law Faculty Scholarship 2013 Secured Transaction History: Protecting Holmes’ Notes Through the Conditional Sales Acts George Lee Flint Jr St. Mary's University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/facarticles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation George Lee Flint, Jr., Secured Transaction History: Protecting Holmes’ Notes Through the Conditional Sales Acts, 44 St. Mary’s L. J. 317 (2013). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE SECURED TRANSACTION HISTORY: PROTECTING HOLMES' NOTES THROUGH THE CONDITIONAL SALES ACTS GEORGE LEE FLINT, JR. * Prelude..............................................318 I. Introduction..........................................321 II. The Gilmorian M odel..................................328 A. Theoretical Underpinnings........................... 328 B. Illegitimate Functions...............................331 C. Coming of Age As a Financing Device ................. 335 D. Redundant Conditional Sales Acts..................... 339 III. The Pre-Act American Decisions ......................... 340 A . The Parties.......................................342 B. The Collateral.................................... -

New York State Task Force Ventilator Allocation Guidelines

VENTILATOR ALLOCATION GUIDELINES New York State Task Force on Life and the Law New York State Department of Health November 2015 Current Members of the New York State Task Force on Life and the Law Howard A. Zucker, M.D., J.D. LL.M. Commissioner of Health, New York State Karl P. Adler, M.D. Cardinal’s Delegate for Health Care, Archdiocese of NY Donald P. Berens, Jr., J.D. Former General Counsel, New York State Department of Health Rabbi J. David Bleich, Ph.D. Professor of Talmud, Yeshiva University, Professor of Jewish Law and Ethics, Benjamin Cardozo School of Law Rock Brynner, Ph.D., M.A. Professor and Author Karen A. Butler, R.N., J.D. Partner, Thuillez, Ford, Gold, Butler & Young, LLP Yvette Calderon, M.D., M.S. Professor of Clinical Emergency Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine Carolyn Corcoran, J.D. Principal, James P. Corcoran, LLC Nancy Neveloff Dubler, LL.B. Consultant for Ethics, NYC Health & Hospitals Corp., Professor Emerita, Albert Einstein College of Medicine Paul J. Edelson, M.D. Professor of Clinical Pediatrics, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University Joseph J. Fins, M.D., M.A.C.P. Chief, Division of Medical Ethics, Weill Medical College of Cornell University Rev. Francis H. Geer, M.Div. Rector, St. Philip’s Church in the Highlands Samuel Gorovitz, Ph.D. Professor of Philosophy, Syracuse University Cassandra E. Henderson, M.D., C.D.E., F.A.C.O.G. Director of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Lincoln Medical and Mental Health Center Hassan Khouli, M.D., F.C.C.P. Chief, Critical Care Section, St. -

Portraits of Notable Iowans

RESEARCH CENTER STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF IOWA (515) 281-6200 [email protected] Photographs Collection – Portraits of Notable Iowans These files may also include portraits of the individual’s spouse and other family members and, occasionally, a photo of their home. Most persons in this list have Iowa connections, but some national and international figures appear in here as well. For more information about these collections, contact us at the email or phone listed above. Available at Des Moines Research Center A Abben, Ben C., Jr. Abbott, Charles H. Abbott, George K. Abercrombie, John C. Abernethy, Alonzo Abernethy, Jacob Abraham, Lot Abrahamson, M.L. Ackerman, Michael Ackiss, J.C. Adams, Austin Adams, Austin (Mrs.) Adams, Elijah Adams, H.C. (Senator) Adams, John (President) Adams, John Quincy (President) Adams, Samuel Adams, William Adams, William T. Adcock, Homer Addleman, William Adkins, John V. Adorno, Paolina Agnew, David Hayes, M.C. Aiken, John Henry Ainslee, Peter (Rev.) Ainsworth, Lucien L. Albert, Elma G. (Judge) Alden, Cynthia Westover Alden, Ebenezer, Jr. Alderman, U.S. Aldrich, Charles Aldrich, C.S. Aldrich, Matilda W. Alexander, Archibald IOWA DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS STATE HISTORICAL BUILDING • 600 E. LOCUST ST. • DES MOINES, IA 50319 • IOWACULTURE.GOV Alexander, Lucy Alexander, Thomas C. Alger, Russell A. Allen, B.F. Allen, Isaac L. Allen, James (Captain, Black Hawk War) nd Allen, James (Captain, 2 Iowa Cavalry) Allen, J.H. (children of) Allen, William Allen, W.S. Allis, Edward P. Allison, William B. Allston, Washington Allyn, George S. Alvord, E.S. Ames, Amos W. Ames, Fisher Ampere, Andre Marie Anderson, Albert R. -

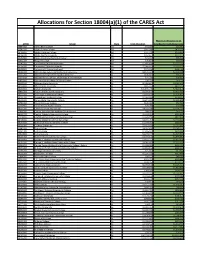

Allocations for Section 18004(A)(1) of the CARES Act

Allocations for Section 18004(a)(1) of the CARES Act Maximum Allocation to be OPEID School State Total Allocation Awarded for Institutional Costs 00884300 Alaska Bible College AK $42,068 $21,034 02541000 Alaska Career College AK $941,040 $470,520 04138600 Alaska Christian College AK $201,678 $100,839 00106100 Alaska Pacific University AK $254,627 $127,313 03160300 Alaska Vocational Technical Center AK $71,437 $35,718 03461300 Ilisagvik College AK $36,806 $18,403 01146200 University Of Alaska Anchorage AK $5,445,184 $2,722,592 00106300 University Of Alaska Fairbanks AK $2,066,651 $1,033,325 00106500 University Of Alaska Southeast AK $372,939 $186,469 00100200 Alabama Agricultural & Mechanical University AL $9,121,201 $4,560,600 04226700 Alabama College Of Osteopathic Medicine AL $186,805 $93,402 04255500 Alabama School Of Nail Technology & Cosmetology AL $77,735 $38,867 03032500 Alabama State College Of Barber Styling AL $28,259 $14,129 00100500 Alabama State University AL $6,284,463 $3,142,231 00100800 Athens State University AL $845,033 $422,516 00100900 Auburn University AL $15,645,745 $7,822,872 00831000 Auburn University Montgomery AL $5,075,473 $2,537,736 00573300 Bevill State Community College AL $2,642,839 $1,321,419 00101200 Birmingham-Southern College AL $1,069,855 $534,927 00103000 Bishop State Community College AL $2,871,392 $1,435,696 03783300 Blue Cliff Career College AL $105,082 $52,541 04267900 Brown Beauty Barber School AL $70,098 $35,049 00101300 Calhoun Community College AL $4,392,248 $2,196,124 04066300 Cardiac And -

The Interior Department, War Department and Indian Policy, 1865-1887

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, History, Department of Department of History 7-1962 The nI terior Department, War Department and Indian Policy, 1865-1887 Henry George Waltmann University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the American Studies Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Waltmann, Henry George, "The nI terior Department, War Department and Indian Policy, 1865-1887" (1962). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 74. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/74 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Copyright by HENRY GEORGE WALTMANN 1963 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE INTERIOR DEPARTMENT, WAR DEPARTMENT AND INDIAN POLICY, 1865-188? by Henry GVc ° Waltmann A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College in the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Under the Supervision of Dr. James C. Olson Lincoln, Nebraska July, 1962 Reproduced -

Santa Fe New Mexican, 08-03-1899 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 8-3-1899 Santa Fe New Mexican, 08-03-1899 New Mexican Printing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing Company. "Santa Fe New Mexican, 08-03-1899." (1899). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/7514 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 0 - f intern jfji-ai-j- . $.X TLL . w ? i ANTA FE NEW MEXICAN, 1899. AND NORTHERN MAIL. NO. 39 VOL. 36. SECOND EDITION SANTA FE, N. M. THURSDAY, AUGUST 3, CITY THREE MORE APPLICANTS, Dlamoad, Watch Repairing A SOUTHERN STORM IN SANTO DOMINGO Opal, Turquols First-Clas- s. THE OUTBREAK THE INNOCENT CADSE "uingg a specialty. Strictly YAQUI Several Applications Eut Ho Enlistments at the Local Recruiting Station, At the recruiting office y there Yellow Fever to A Florida Town and Valu The Murder of the President Was S. The Tribesmen at Work in Arizona Man Who Brought Destroyed were three applications for enlistment, SPITZ, Out to Sea Not Planned, But There Is a Revo- but the were all under age, Are Called Home to Aid in , the Soldiers' Home Has Been able Property Swept applicants and had not secured consent of their Wind and Wave. lution All the Same, . -

Why Judges Resign: Influences on Federal Judicial Service, 1789 to 1992

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. Why Judges Resign: Influences on Federal Judicial Service, 1789 to 1992 146891 U.S. Department of Justice Natlonallnsmute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the autllors and do not necessarily represent the oHicia1 position or policies of the Natlona11nstitute of Justice, Permission to reproduce this • r t 1 material has been gm.nletl.l:'U.Dl.J.C b.v • DomaJ.n, Federal JudJ.cJ.al Center to the National Criminal J~stlce Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the~owner. :ral Judicial History Office !ral Judicial Center Why Judges Resign: Influences on Federal Judicial Service, 1789 to 1992 By Emily Field Van Tassel With Beverly Hudson Wirtz and Peter Wonders Federal Judicial History Office Federal Judicial Center 1993 Prepared for the National Commission on Judicial Discipline and Removal. Thb Federal Judicial Center publication was undertaken in furtherance of the Cen ter's statutory mission to conduct and stimulate research and development for the improvement of judicial administration. The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Judicial Center. Table of Contents 1. Introduction I 2. Overview 5 The Growth of the Federal Judiciary 5 Changes in Judicial Tenure 7 Judicial Resignations as a Percentage of the Total Judiciary: Change Over Time 7 \'V'hy ] udges Resign 10 Age and/or health (including disability and pre-I9I9 retirement) 10 Appointment to other office/elected office 10 Dissatisfaction II Return to private practice, other employment, imdeq uate salary 12- Allegations of misbehavior (including impeachments and convictions) 17 3. -

The Development of Council Bluffs As a Staging Area

THE DEVELOPMENT OF COUNCIL BLUFFS AS A STAGING AREA FOR WESTERN SETTLEMENT, 1838-1869 A Thesis Presented to The School of Graduate Studies Drake University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History by Sidney Halma August 1972 /Cf /fp~ 1-//6 lea) THE DEVELOPl1ENT OF COUNCIL BLUFFS AS A STAGING AREA FOR \.JESTERN SETTLEMENT. 1838-1869 by Sidney Halma Approved by Committee: TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF MAPS iv LIST OF FIGURES v Chapter 1. INTRODUCT ION . 1 2. "SENTERAL TO SEVERAL NATIONS," 1838-1846 5 3. "THE MECCA ON THE MISSOURI," 1846-1848 20 4. THE GATHERING OF ISRAEL, 1847-1852 39 5. NEW LEADERSHIP, 1853-1856 59 6. "SPEARHEAD OF THE FRONTIER," 1857-1862 76 7. "STAR OF THE NORTHWEST," 1863-1869 .. 90 8. COUNCIL BLUFFS WINS BUT OMAHA TAKES THE PRIZE 108 9. "LIVING TOO MUCH OFF THE PAST" 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 120 APPENDIX 130 LIST OF MAPS Map Page 1. Northern Plains and Rocky Mountains, 18l9~1843 • 6 2. Map of the Vicinity of Council Bluffs l' .. • • • 13 3. Routes to the Gold Fields and Oregon • • 46 4. Location of Council Bluffs in Relationship to the Lewis and Clark Expedition . • • • • • . .• . 131 5. Routes of the Proposed Yellowstone Expedition 132 6. Map Showing Winter Quarters of the Yellowstone Expedition, 1819 ..... .... 133 7. Map Illustrating the Pottawattamie Cession and the Act of 1847 . 139 8. Map Showing a Saving of 200 Miles . 140 9. Map Illustrating Route from Dubuque to Denver via Council Bluffs . 141 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page L Differences in Prices of Commodities at Kanesville Between the Years 1849 and 1850 .