Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ester Boserup's Legacy on Sustainability Orientations for Contemporary Research Fischer-Kowalski, Marina; Reenberg, Anette; Schaffartzik, Anke ; Mayer, Andreas

Ester Boserup's legacy on Sustainability Orientations for Contemporary Research Fischer-Kowalski, Marina; Reenberg, Anette; Schaffartzik, Anke ; Mayer, Andreas DOI: 10.1007/978-94-017-8678-2 Publication date: 2014 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Fischer-Kowalski, M., Reenberg, A., Schaffartzik, A., & Mayer, A. (Eds.) (2014). Ester Boserup's legacy on Sustainability: Orientations for Contemporary Research. Springer. Human - Environment Interactions Vol. 4 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8678-2 Download date: 26. sep.. 2021 Ester Boserup’s Legacy on Sustainability Human-Environment Interactions VOLUME 4 Series Editor: Professor Emilio F. Moran, Michigan State University (Geography) Editorial Board: Barbara Entwisle, Univ. of North Carolina (Sociology) David Foster, Harvard University (Ecology) Helmut Haberl, Klagenfurt University (Socio-ecological System Science) Billie Lee Turner II, Arizona State University (Geography) Peter H. Verburg, University of Amsterdam (Environmental Sciences, Modeling) For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/8599 Marina Fischer-Kowalski • Anette Reenberg Anke Schaffartzik • Andreas Mayer Editors Ester Boserup’s Legacy on Sustainability Orientations for Contemporary Research Editors Marina Fischer-Kowalski Anke Schaffartzik Institute of Social Ecology Institute of Social Ecology Alpen Adria University Alpen Adria University Vienna Vienna Austria Austria Anette Reenberg Andreas Mayer Dept. Geosciences & Resource Mgmt Institute -

The Emergence of Radical/Critical Geography Within North America

The Emergence of Radical/Critical Geography within North America Linda Peake1 Urban Studies Program, Department of Social Science York University, Canada [email protected] Eric Sheppard Department of Geography University of California, Los Angeles, USA [email protected] Abstract In this paper we aim to provide a historical account of the evolution of Anglophone radical/critical geography in North America. Our account is structured chronologically. First, we examine the spectral presence of radical / critical geography in North America prior to the mid-sixties. Second, we narrate the emergence of both radical and critical geography between 1964 / 1969 until the mid-1980s, when key decisions were taken that moved radical / critical geography into the mainstream of the discipline. Third, we examine events since the mid- 1980s, as radical geography merged into critical geography, becoming in the process something of a canon in mainstream Anglophone human geography. We conclude that while radical / critical geography has succeeded in its aim of advancing critical geographic theory, it has been less successful in its aim of 1 Published under Creative Commons licence: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 2 Eric’s first exposure was as an undergraduate at Bristol in 1971 when the newly hired lecturer Keith Bassett, freshly returned from Penn State, brought a stack of Antipodes to one of his lectures. Linda’s radical awakening also came in the UK, in the late 1970s courtesy of her lecturers at Reading University. Sophie Bowlby took her The Emergence of Radical/Critical Geography in North America 306 increasing access to the means of knowledge production to become a peoples’ geography that is grounded in a desire for working towards social change. -

King's Research Portal

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1177/1363460718779209 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Hubbard, P. (2018). Geography and sexuality: why space (still) matters. SEXUALITIES, 21(8), 1295-1299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460718779209 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Grounded Theologies: 'Religion' and the 'Secular' in Human Geography

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Singapore Management University Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Research Collection School of Social Sciences School of Social Sciences 2-2013 Grounded theologies: ‘Religion’ and the ‘secular’ in human geography Justin Kh TSE Singapore Management University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soss_research Part of the Geography Commons, and the Religion Commons Citation TSE, Justin Kh.(2013). Grounded theologies: ‘Religion’ and the ‘secular’ in human geography. Progress in Human Geography, 38(2), 201-220. Available at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soss_research/3134 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Social Sciences at Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Collection School of Social Sciences by an authorized administrator of Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. For more information, please email [email protected]. Article Progress in Human Geography 2014, Vol. 38(2) 201–220 ª The Author(s) 2013 Grounded theologies: Reprints and permission: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav ‘Religion’ and the ‘secular’ DOI: 10.1177/0309132512475105 in human geography phg.sagepub.com Justin K.H. Tse The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada Abstract This paper replies to Kong’s (2010) lament that geographers of religion have not sufficiently intervened in religious studies. It advocates ‘grounded theologies’ as a rubric by which to investigate contemporary geographies of religion in a secular age. -

The Story of My Face: How Environmental Stewards Perceive Stigmatization (Re)Produced by Discourse

Sustainability 2010, 2, 3339-3353; doi:10.3390/su2113339 OPEN ACCESS sustainability ISSN 2071-1050 www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability Article The Story of My Face: How Environmental Stewards Perceive Stigmatization (Re)produced By Discourse Jutta Gutberlet 1,* and Bruno de Oliveira Jayme 2 1 Department of Geography, University of Victoria, P.O. Box 3060 STN CSC, Victoria, B.C., V8W 3R4, Canada 2 Interdisciplinary Program, University of Victoria, P.O. Box 3060 STN CSC, Victoria, B.C., V8W 3R4, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-250-472-4537; Fax: +1-250-721-6216. Received: 25 August 2010; in revised form: 19 October 2010 / Accepted: 21 October 2010 / Published: 27 October 2010 Abstract: The story of my face intertwines concepts of social semiotics and discourse analysis to explore how a simple type of printed media (flyer) can generate stigmatization of informal recyclers, known as binners in Western Canada. Every day, media exposes humans to signifiers (e.g., words, photographs, cartoons) that appear to be trivial but influence how we perceive their meaning. Amongst the signifiers frequently found in the media, the word “scavengers”, has been used to refer to autonomous recyclers. Specific discourse has the potential to promote and perpetuate discrimination against the individuals who deal with selective collection of recyclables and decrease the value of their work. Their work is valuable because it generates income for recyclers, recovers resources and improves overall environmental health. In this context, the present qualitative study draws on data collected with binners during research conducted in the city of Victoria, in British Columbia. -

DCDC 2011-2012 Annual Progress Report Decision Center for A

DCDC 2011-2012 Annual Progress Report Decision Center for a Desert City II: Urban Climate Adaptation SES-0951366 Principal Investigators Dave White (PI, Co-Director) Charles Redman (Co-PI, Co-Director) Craig Kirkwood (Co-PI) Margaret Nelson (Co-PI) Submitted to the National Science Foundation Via Fastlane June 1, 2012 Decision Center for a Desert City II DCDC 2011-2012 Principal Investigators: Table of Contents Dave White (PI, Co-Director) Charles Redman (Co-PI, Co-Director) I. Introduction to DCDC 3 Craig Kirkwood (Co-PI) Margaret Nelson (Co-PI) II. Findings of Research Activities 14 Executive Committee: Dave White Craig Kirkwood III. Education and Development 18 Kelli Larson Margaret Nelson IV. Outreach Activities 20 Charles Redman V. Kerry Smith Liz Marquez V. Contributions 25 Staff: VI. Partner Organizations 28 Katja Brundiers Sarah Jones Taylor Ketchum VII. DCDC Participants 33 Liz Marquez Estella O’Hanlon Annissa Olsen Ray Quay David Sampson Sally Wittlinger Teams: Adaptation Decision Analysis Decision Processes Institutional Roles in Decision Making Boundary Studies Education and Resource Development Outcomes Distributional Effects Economic Feedbacks Urban System Impacts Uncertainties Climate Change - 2 - I. Introduction to DCDC The Decision Center for a Desert City (DCDC) at Arizona State University (ASU) was established in 2004 by the National Science Foundation (NSF) to advance scientific understanding of environmental decision making under conditions of uncertainty. Bolstered by new funding from the NSF, “DCDC II” was launched in October 2010 to expand its already-extensive research agenda, further engage the policy community, and forge stronger ties between knowledge and action. In this second phase of DCDC funding, we are developing new fundamental knowledge about decision making from three interdisciplinary perspectives: climatic uncertainties, urban-system dynamics, and adaptation decisions. -

Re Ections on the 'Cultural Turn' in British Human Geography

Norsk geogr. Tidsskr. Vol. 55, 166–172. Oslo. ISSN 0029-1951 Whatever happened to the social? Re ections on the ‘cultural turn’ in British human geography GILL VALENTINE Valentine, G. 2001. Whatever happened to the social? Re ections on the ‘cultural turn’ in British human geography. Norsk Geo- gra sk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography Vol. 55, 166–172. Oslo. ISSN 0029-1951. This paper focuses on the ‘cultural turn’ which has taken place in British and to a lesser extent North American and Australian human geography in the last decade. It begins by exploring what constitutes the cultural in what has been dubbed ‘new cultural geography’. It then explores contemporary claims that cultural geography has eclipsed or marginalised social geography. The nal section evaluates these claims about the demise of the social, arguing that the social has not been evacuated but rather has been rede ned. While this paper tells a speci c story about a particular tradition and geographical frame of reference, it nonetheless has wider relevance because it provides an example of the differential development of particular sub-disciplinar y areas, of the way sub- disciplinary knowledges shape each other, and of the way understanding s of disciplinar y trends are contested. Keywords: cultural turn, geographical thought, social Gill Valentine, Department of Geography, University of Shef eld, Winter Street, Shef eld, S10 2TN, UK. E-mail: G.Valentine@ shef eld.ac.uk Introduction dimensions. (Jackson 1989). Methodologically, Sauer was in uenced by anthropology, from which he derived a This paper focuses on the ‘cultural turn’ which has taken commitment to ethnographic eld research. -

Geography & Env Planning (GE)

Geography & Env Planning (GE) 1 GE 3080 Economic Geography (4) GEOGRAPHY & ENV Introduces students to the major themes and issues addressed in critical economic geography. Focuses on development, resources, theories, and PLANNING (GE) the impacts of economic systems across the global landscape. Gives students a greater appreciation and understanding of the myriad of GE 2002 Human Geography (3) cultural political and economics forces shaping our world. Fall of even Provides Geography and Environmental Planning majors an introduction years. to the field of human geography, with a particular focus on the various GE 3260 The Physical Geography of National Parks (3) subfields and their relationship to the social sciences. A general A survey of the physical geography of the United States through a introduction to the field, open to any student. Reviews key concepts, sample of our National Parks. These Parks have within them examples of viewpoints and methods of cultural geographers in examining how many diverse landforms and demonstrate the tectonic and geomorphic human activity is organized. Springs. processes responsible for the evolution of landforms throughout the GE 2040 Digital Cartography (2) United States. Using the example of the National Parks, examines the The basic elements of Cartography are discussed and illustrated with tectonics of the Eastern and Western United States, the effects of alpine practical experience. Students learn the principles of effective digital and continental glaciation and periglacial processes, and the impact of mapping and become familiar with the types of problems that Geographic fluvial processes within the context of landscape regions such as the Information Systems (GIS) can solve. -

Master of Science in Development Statistics Programme 2008-2015

www.sta.uwi.edu/postgrad/ Master of Science in Development Statistics Programme 2008-2015 SIR ARTHUR LEWIS INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC STUDIES (SALISES) MASTER OF SCIENCE IN DEVELOPMENT STATISTICS PROGRAMME 2008 - 2015 M.Sc. in Development Statistics ..............................................................................................................2 Graduates of M.Sc. in Development Statistics Programme ...........................................................6 Lecturers of M.Sc. in Development Statistics Programme ..........................................................20 Admission Procedures .............................................................................................................................28 Throughput of the M.Sc. in Development Statistics .....................................................................28 Projected Throughput for 2008-2016 ................................................................................................29 Non-Trinidad and Tobago Applicants ................................................................................................29 Student Engagement M.Sc. Graduates-Development Statistics ..............................................30 Career Paths After Graduation M.Sc. Graduates-Development Statistics .............................30 The Jack Harewood Award ....................................................................................................................30 SALISES Graduates Master of Science in Development Statistics ............................................31 -

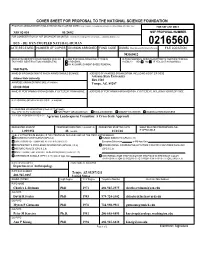

Cover Sheet for Proposal to the National Science Foundation

COVER SHEET FOR PROPOSAL TO THE NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION PROGRAM ANNOUNCEMENT/SOLICITATION NO./CLOSING DATE/if not in response to a program announcement/solicitation enter NSF 02-2 FOR NSF USE ONLY NSF 02-010 01/24/02 NSF PROPOSAL NUMBER FOR CONSIDERATION BY NSF ORGANIZATION UNIT(S) (Indicate the most specific unit known, i.e. program, division, etc.) BCS - BE: DYN COUPLED NATURAL-HUMAN 0216560 DATE RECEIVED NUMBER OF COPIES DIVISION ASSIGNED FUND CODE DUNS# (Data Universal Numbering System) FILE LOCATION 943360412 EMPLOYER IDENTIFICATION NUMBER (EIN) OR SHOW PREVIOUS AWARD NO. IF THIS IS IS THIS PROPOSAL BEING SUBMITTED TO ANOTHER FEDERAL TAXPAYER IDENTIFICATION NUMBER (TIN) A RENEWAL AGENCY? YES NO IF YES, LIST ACRONYM(S) AN ACCOMPLISHMENT-BASED RENEWAL 860196696 NAME OF ORGANIZATION TO WHICH AWARD SHOULD BE MADE ADDRESS OF AWARDEE ORGANIZATION, INCLUDING 9 DIGIT ZIP CODE Arizona State University Arizona State University Box 3503 AWARDEE ORGANIZATION CODE (IF KNOWN) Tempe, AZ. 85287 0010819000 NAME OF PERFORMING ORGANIZATION, IF DIFFERENT FROM ABOVE ADDRESS OF PERFORMING ORGANIZATION, IF DIFFERENT, INCLUDING 9 DIGIT ZIP CODE PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE (IF KNOWN) IS AWARDEE ORGANIZATION (Check All That Apply) (See GPG II.C For Definitions) FOR-PROFIT ORGANIZATION SMALL BUSINESS MINORITY BUSINESS WOMAN-OWNED BUSINESS TITLE OF PROPOSED PROJECT Agrarian Landscapes in Transition: A Cross-Scale Approach REQUESTED AMOUNT PROPOSED DURATION (1-60 MONTHS) REQUESTED STARTING DATE SHOW RELATED PREPROPOSAL NO., IF APPLICABLE $ 1,999,952 48months 01/01/03 CHECK APPROPRIATE BOX(ES) IF THIS PROPOSAL INCLUDES ANY OF THE ITEMS LISTED BELOW BEGINNING INVESTIGATOR (GPG I.A) HUMAN SUBJECTS (GPG II.C.11) DISCLOSURE OF LOBBYING ACTIVITIES (GPG II.C) Exemption Subsection or IRB App. -

A Preliminary Assessment Zusammenfassung: Postmoderne Geographie Des Men- Schen. Eine Vorläufige Bilanz Der Nachfolgende Beitra

2 Erdkunde Band 48/1994 POSTMODERN HUMAN GEOGRAPHY A preliminary assessment MICHAEL DEAR Zusammenfassung: Postmoderne Geographie des Men-authority being threatened; incomprehension on the schen. Eine vorläufige Bilanz part of those who (for whatever reason) failed to Der nachfolgende Beitrag versucht eine vorläufige Bilanz negotiate its arcane jargon; and the indifference of the des Einflusses des postmodernen Denkansatzes auf die majority, who have ignored what they presumably Geographie des Menschen während des vergangenen perceived as the latest fad. On the ideological left, Jahrzehnts zu geben. Eine einheitliche Theorie der Post- postmodernism encountered few friends, since moderne gibt es nicht. Ihre philosophischen Ursprünge können bis ins 19. Jahrhundert zurückverfolgt werden, progressives viewed its pluralist (some say neo- obwohl der Begriff selbst erst seit den 30er Jahren gebräuch- conservative) sentiments with suspicion. There were lich wurde. Konzepte der Postmoderne im Sinne von Stil, even fewer allies on the right, whose crusade to Epoche und Methode werden geprüft, um das Verständnis preserve the established canons of Western culture für eine höchst schillernde Terminologie zu fördern. transformed this same pluralism into the arcane Zusammen mit der Bewegung des Dekonstruktivismus hat obligations of "political correctness". der Ansatz des postmodernen Denkens zahlreiche philo- Despite the combined armies of antipathy and iner- sophischen Grundlagen der Aufklärung und des "moder- tia, postmodernism has flourished. I believe this is nen" Denkens in Frage gestellt. Im Bereich der Geographie because it constitutes the most profound challenge to des Menschen können Spuren des postmodernen Denk- ansatzes in der quantitativen Revolution und im Wieder- three hundred years of post-Enlightenment thinking. aufleben der marxistischen Sozialtheorie entdeckt werden. -

«M 12Name» «Last Name»«Suffix»

American Philosophical Society HELD AT PHILADELPHIA FOR PROMOTING USEFUL KNOWLEDGE WWW . AMPHILSOC . ORG Election of New Members to the American Philosophical Society April 23, 2021 The following were offered membership in the Society: CLASS 1 MATHEMATICAL AND PHYSICAL SCIENCES Joseph S. Francisco President’s Distinguished Professor of Earth and Environmental Science, Professor of Chemistry, University of Pennsylvania; William E. Moore Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences and Chemistry, Purdue University Email: [email protected] Barbara V. Jacak Director, Nuclear Science Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Professor of Physics, University of California, Berkeley Email: [email protected] Deb Niemeier Clark Distinguished Chair Professor, Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering, Director, Maryland Transportation Institute, University of Maryland Email: [email protected] Daniel G. Nocera Patterson Rockwood Professor of Energy, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Harvard University; Founder and Board of Directors, Kula Bio Email: [email protected] Billie Lee Turner II Distinguished Sustainability Scientist, Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation, Regents’ Professor, Gilbert F. White Professor of Environment and Society, School of the Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning and School of Sustainability, Arizona State University; Distinguished Research Professor of Geography, Clark University Email: [email protected] International Michael Victor Berry