The Third Annual Jerome M. Culp Memorial Lecture: the Zombie Jamboree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

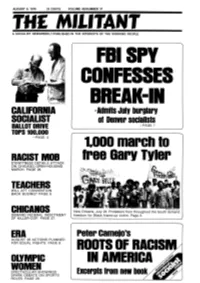

1 ..000 March to Tree Gary Tyler

AUGUST 6, 1976 25 CENTS VOLUME 40/NUMBER 31 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY /PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Militant/Harry Ring CALIFORNIA ·Admits July burglary SOCIALIST ol Denver socialists BALLOT DRIVE -PAGE 7 TOPS 100.000 -PAGE 4 1.. 000 march to RACIST MOB tree Gary TYler EYEWITNESS DETAILS ATTACK ON CHICAGO OPEN-HOUSING MARCH. PAGE 28. TEACHERS WILL AFT CONVENTION BACK BUSING? PAGE 9. - MIIIT"n"·'""' Aber CHICANOS New Orleans, July 24. Protesters from throughout the South demand DEMAND FEDERAL INDICTMENT freedom for Black frame-up victim. Page 3. OF KILLER-COP. PAGE 27-. ERA Peter CameJo's AUGUST 26 ACTIONS PLANNED FOR EQUAL RIGHTS. PAGE 8. ROOTS OF RACIS OLYMPIC II A ERICA WOMEN SPECTACULAR SHOWINGS SPARK DEBATE ON SPORTS Excerpts lrom new book ROLES. PAGE 28. In Brief TIBBS GETS NEW TRIAL: The Florida State Supreme Rogers. The workers were seeking a >L1 percent increase in Court has reversed the murder and rape convictions of wages. Delbert Tibbs. With the death penalty about to go into effect The city fired all li17 strikers and hired scabs. On ,July 1i1 in Florida, the thirty-five-year-old Black man's life was in city officials announced that all the jobs would be filled by imminent danger. The high court ordered a new trial for the next day, prompting a number of strikers to return. THIS Tibbs because of conflicts in trial testimony. Union leaders called off the strike July 16. Fewer than one Tibbs, a writer from Chicago, was hitchhiking through third of the strikers were rehired. -

The Zombie Jamboree by Anthony Paul Farley

Page 1 FIU Law Review Fall, 2008 4 FIU L. Rev. 175 LENGTH: 4685 words Symposium: Twelfth Annual LatCrit Conference Critical Localities: Epistemic Communities, Rooted Cosmopolitans, New Hegemonies and Knowledge Processes: The Third Annual Jerome M. Culp Memorial Lecture: The Zombie Jamboree(c) (c) Anthony Paul Farley 2007. NAME: Anthony Paul Farley* BIO: * James Campbell Matthews Distinguished Professor of Jurisprudence at Albany Law School and Haywood Burns Chair in Civil Rights at CUNY School of Law during 2006-2007. It was an honor and a joy to give the Third Annual Jerome M. Culp Memorial Lecture at LatCrit XII: Critical Localities at Florida International University School of Law. Jerome was dedicated to Critical Race Theory and to LatCrit. Lat- Crit has sustained critical race theories and critical race theorists for twelve years now. No one knows what will happen tomorrow, but our vitality, our ability to face tomorrow, as intellectual movements and as individual thinkers, must surely have something to do with the way we remember those whose past efforts made today possible. Although what follows is the text on which I based my lecture, please think of it as a line of flight and a point of departure. I departed from it quite freely in Miami. This essay, Zombie Jamboree, is a memorial meant for singing and for flight and for departures: We have been naught, we shall be all. Thanks to all my colleagues at Albany Law School. Thanks to all my colleagues at CUNY School of Law, 2006-2007. Thanks to Keith Aoki, Steve Bender, Christopher Carbot, Bob Chang, Angela Harris, Charles Pouncy, Frank Valdes, and everyone else involved in LatCrit XII. -

Death Penally -&Ary Tyler: How Court Ruling Will Attect His Case ·Reactionary Decision Sparks Broad Opposition -PAGES 4-6

JULY 16, 1976 25 CENTS VOLUME 40/NUMBER 28 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE ·Blacks are chiel victim ol death penallY -&ary TYler: how court ruling will attect his case ·Reactionary decision sparks broad opposition -PAGES 4-6 socialist candidates blast .death penallY ·Hit Ford, carter stands [Peter Camejo and Willie Mae Reid, Socialist Workers party candidates for president and vice president, released the following statement July 7.] The Supreme Court ruling upholding the death penalty is a stunning setback for all working people. It is bitterly ironic that on the two hundredth anniver sary of the American revolution the men in black robes sanctioned a practice that has more in common with the Dark Ages than the ideals of the revolutionaries of 1776. Continued on page 5 In Brief THIS PETER CAMEJO TO ANSWER DEMOCRATS: Social 'WOMAN'S EVOLUTION' AT HARVARD: Even the ist Workers party presidential candidate Peter Camejo will ivy-covered bastion of male academia is not impervious to a answer the decisions of the Democratic party convention at feminist view of the origins of women s oppression. This fall WEEK'S a public meeting July 16. He will also outline his party's Harvard students in Natural Science 36, the course on perspective for independent political action at the rally, "Biological Determinism," will be reading selections from MILITANT which will begin at 7:30 p.m. at the Community Church, 40 Woman's Evolution by Marxist anthropologist Evelyn Reed. 3 Jury weighs fate E. Thirty-fifth Street, in New York. -

Rhonda Cato: a 'Beautiful by Michael K

n. Blaell Stll.eat Voice of Nonll... t .... UDivaaity 0 • December 1, 1976 IIIIIAIGII Black vote lfiiCIIIY elects ·Carter Ill tbousalds of votes cast for acll candidate ~IU(I[ CARTER • by 2,071,506 and also defeated · the most powerful weapons by Anthony Jenkins against Republicans. Republicans PENNSYLVANIA President Ford in the electoral Onyx Staff Z.IZ3WN college; by a very slim margin. can no longer. afford to overlook -2t President-elect Carter r~eived blacks in any areas. It is also reasonable to say that President-elect Jimmy Caner Ford won 55 Ofo of the white OHIO many congratulations from well 1.111Mfi had President Ford payed more .lost the white' popular vote 47 .60Jo vote in the South, yet Carter's wishers while President Ford, who attention to blacks he might have to 51.3% IN THE 'Nov. 2 massive black support in that area maintained his proud image after MISSOURI picked up more votes from the Presidedtial Eiection, but he won made th.e South solid for him. I MW-1• losing to Caner, works diligently minorities that could have cut the roughly 920To of the ~.6 million The 52-year-old former Gover 12 to help make a smooth transition to the office of the presidency for 2,000,000 vote deficit to win the black votes·.cast and will become nor from Plains, Ga. defeated the TEXAS popular vote. the 39th President of the United incumbent President after . he I 1.74SMIM President-elect Carter. Black politicians wanted hope, States because of his black served his country for two years in The election was won for LOUISIANA promises and verbal commit support. -

Hat a Sadlowski Victory Can Mean -STEEL SUPPLEMENT, PAGES 15-20 Militanvstu Singer -ELECTION NEWS, PAGES 4,5 Ed Sadlowski, Insurgent Candidate for Top Union Post

JANUARY 21, 1977 25 CENTS VOLUME 41 I NUMBER 2 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE SPECIAL STEEL ISSUE hat a Sadlowski victory can mean -STEEL SUPPLEMENT, PAGES 15-20 MilitanVStu Singer -ELECTION NEWS, PAGES 4,5 Ed Sadlowski, insurgent candidate for top union post ,,.-- .,_,:---.<''- --" ~ '{·'':/',;/-').:·< THIS In Brief WEEK'S SUPPORT BUILDS IN MICH. FREE SPEECH Christmas Eve fire that killed twelve people. FIGHT: MIT Prof. Noam Chomsky. Joe Madison, president Militant correspondent Joyce Stoller reports that neigh MILITANT of the Detroit NAACP. Edith Tiger, director of the National bors protested the fatal consequences of the lack of bilingual fire fighters in Chicago. Rescue operations were crippled 4 Steel election battle Emergency Civil Liberties Committee. Eqbal Ahmad of the Institute for Policy Studies. Lehman Brightman of the because firemen were unable to communicate with people enters final weeks Native American studies ·department at Contra Costa trapped in the burning building. 5 Perspectiva Mundial: College. Mary Gonzales, speaking for the Pilsen Neighbors 'A real breakthrough' These are among the new endorsers of the Committee for Community Council, charged that three of the city's four Free Speech. The committee was set up to defend three snorkel rescue units were used to fight a warehouse fire 6 Hoosiers, Georgians members of the Young Socialist A1liance who each face where no human lives were threatened at the same time five demand: 'Ratify the ERA!' penalties of up to $1,650 in fines and six months in jail on people were consumed in the January 2 blaze. 7 Where Gary Tyler charges of "criminal trespass" and "illegally occupying a "What it comes down to," Gonzales said, "is what do the case stands today university building by force." firemen consider more important, human lives or private The three-Brigid Douglas, Tom Smith, and Jim property?" 8 New FBI guidelines Garrison-were arrested October 20 while distributing authorize informers Socialist Workers election campaign literature outside a CALIF.