Taking Good Works to the Next Level: Increasing Investment in and Support for Higher-Risk Innovation Jessie Capper Claremont Mckenna College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Philanthropy Forum Conference April 18–20 · Washington, Dc

GLOBAL PHILANTHROPY FORUM CONFERENCE APRIL 18–20 · WASHINGTON, DC 2017 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference This book includes transcripts from the plenary sessions and keynote conversations of the 2017 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference. The statements made and views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of GPF, its participants, World Affairs or any of its funders. Prior to publication, the authors were given the opportunity to review their remarks. Some have made minor adjustments. In general, we have sought to preserve the tone of these panels to give the reader a sense of the Conference. The Conference would not have been possible without the support of our partners and members listed below, as well as the dedication of the wonderful team at World Affairs. Special thanks go to the GPF team—Suzy Antounian, Bayanne Alrawi, Laura Beatty, Noelle Germone, Deidre Graham, Elizabeth Haffa, Mary Hanley, Olivia Heffernan, Tori Hirsch, Meghan Kennedy, DJ Latham, Jarrod Sport, Geena St. Andrew, Marla Stein, Carla Thorson and Anna Wirth—for their work and dedication to the GPF, its community and its mission. STRATEGIC PARTNERS Newman’s Own Foundation USAID The David & Lucile Packard The MasterCard Foundation Foundation Anonymous Skoll Foundation The Rockefeller Foundation Skoll Global Threats Fund Margaret A. Cargill Foundation The Walton Family Foundation Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation The World Bank IFC (International Finance SUPPORTING MEMBERS Corporation) The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust MEMBERS Conrad N. Hilton Foundation Anonymous Humanity United Felipe Medina IDB Omidyar Network Maja Kristin Sall Family Foundation MacArthur Foundation Qatar Foundation International Charles Stewart Mott Foundation The Global Philanthropy Forum is a project of World Affairs. -

The Marshall Project/California Sunday Magazine

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 2019 Carroll Bogert PRESIDENT Susan Chira EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Neil Barsky FOUNDER AND CHAIRMAN BOARD OF DIRECTORS Fred Cummings Nicholas Goldberg Jeffrey Halis Laurie Hays Bill Keller James Leitner William L. McComb Jonathan Moses Ben Reiter Topeka Sam Liz Simons (Vice-Chair) William J. Snipes Anil Soni ADVISORY BOARD Soffiyah Elijah Nicole Gordon Andrew Jarecki Marc Levin Joan Petersilia David Simon Bryan Stevenson CREDITS Cover: Young men pray at Pine Grove Youth Conservation Camp—California’s first and only remaining rehabilitative prison camp for offenders sentenced as teens. Photo by Brian Frank for The Marshall Project/California Sunday Magazine. Back cover: Photo credits from top down: WILLIAM WIDMER for The Marshall Project, Associated Press ELI REED for The Marshall Project. From Our President and Board Chair Criminal justice is a bigger part of our national political conversation than at any time in decades. That’s what journalism has the power to do: raise the issues, and get people talking. In 2013, when trying to raise funds for The Marshall Proj- more than 1,350 articles with more than 140 media part- ect’s launch, we told prospective supporters that one ners. Netflix has turned our Pulitzer-winning story, “An of our ambitious goals was for criminal justice reform to Unbelievable Story of Rape,” into an eight-part miniseries. be an integral issue in the presidential debates one day. We’ve reached millions of Americans, helped change “I would hope that by 2016, no matter who the candidates laws and regulations and won pretty much every major are… that criminal justice would be one of the more press- journalism prize out there. -

Investing in Equitable News and Media Projects

Investing in Equitable News and Media Projects Photo credit from Left to Right: Artwork: “Infinite Essence-James” by Mikael Owunna #Atthecenter; Luz Collective; Media Development Investment Fund. INVESTING IN EQUITABLE NEWS AND MEDIA PROJECTS AUTHORS Andrea Armeni, Executive Director, Transform Finance Dr. Wilneida Negrón, Project Manager, Capital, Media, and Technology, Transform Finance ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Farai Chideya, Ford Foundation Jessica Clark, Dot Connector Studio This work benefited from participation in and conversations at the Media Impact Funders and Knight Media Forum events. The authors express their gratitude to the organizers of these events. ABOUT TRANSFORM FINANCE Transform Finance is a nonprofit organization working at the intersection of social justice and capital. We support investors committed to aligning their impact investment practice with social justice values through education and research, the development of innovative investment strategies and tools, and overall guidance. Through training and advisory support, we empower activists and community leaders to shape how capital flows affect them – both in terms of holding capital accountable and having a say in its deployment. Reach out at [email protected] for more information. THIS REPORT WAS PRODUCED WITH SUPPORT FROM THE FORD FOUNDATION. Questions about this report in general? Email [email protected] or [email protected]. Read something in this report that you’d like to share? Find us on Twitter @TransformFin Table of Contents 05 I. INTRODUCTION 08 II. LANDSCAPE AND KEY CONSIDERATIONS 13 III. RECOMMENDATIONS 22 IV. PRIMER: DIFFERENT TYPES OF INVESTMENTS IN EARLY-STAGE ENTERPRISES 27 V. CONCLUSION APPENDIX: 28 A. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 29 B. LANDSCAPE OF EQUITABLE MEDIA INVESTORS AND ADJACENT INVESTORS I. -

Threat from the Right Intensifies

THREAT FROM THE RIGHT INTENSIFIES May 2018 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................1 Meeting the Privatization Players ..............................................................................3 Education Privatization Players .....................................................................................................7 Massachusetts Parents United ...................................................................................................11 Creeping Privatization through Takeover Zone Models .............................................................14 Funding the Privatization Movement ..........................................................................................17 Charter Backers Broaden Support to Embrace Personalized Learning ....................................21 National Donors as Longtime Players in Massachusetts ...........................................................25 The Pioneer Institute ....................................................................................................................29 Profits or Professionals? Tech Products Threaten the Future of Teaching ....... 35 Personalized Profits: The Market Potential of Educational Technology Tools ..........................39 State-Funded Personalized Push in Massachusetts: MAPLE and LearnLaunch ....................40 Who’s Behind the MAPLE/LearnLaunch Collaboration? ...........................................................42 Gates -

US Mainstream Media Index May 2021.Pdf

Mainstream Media Top Investors/Donors/Owners Ownership Type Medium Reach # estimated monthly (ranked by audience size) for ranking purposes 1 Wikipedia Google was the biggest funder in 2020 Non Profit Digital Only In July 2020, there were 1,700,000,000 along with Wojcicki Foundation 5B visitors to Wikipedia. (YouTube) Foundation while the largest BBC reports, via donor to its endowment is Arcadia, a Wikipedia, that the site charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and had on average in 2020, Peter Baldwin. Other major donors 1.7 billion unique visitors include Google.org, Amazon, Musk every month. SimilarWeb Foundation, George Soros, Craig reports over 5B monthly Newmark, Facebook and the late Jim visits for April 2021. Pacha. Wikipedia spends $55M/year on salaries and programs with a total of $112M in expenses in 2020 while all content is user-generated (free). 2 FOX Rupert Murdoch has a controlling Publicly Traded TV/digital site 2.6M in Jan. 2021. 3.6 833,000,000 interest in News Corp. million households – Average weekday prime Rupert Murdoch Executive Chairman, time news audience in News Corp, son Lachlan K. Murdoch, Co- 2020. Website visits in Chairman, News Corp, Executive Dec. 2020: FOX 332M. Chairman & Chief Executive Officer, Fox Source: Adweek and Corporation, Executive Chairman, NOVA Press Gazette. However, Entertainment Group. Fox News is owned unique monthly views by the Fox Corporation, which is owned in are 113M in Dec. 2020. part by the Murdoch Family (39% share). It’s also important to point out that the same person with Fox News ownership, Rupert Murdoch, owns News Corp with the same 39% share, and News Corp owns the New York Post, HarperCollins, and the Wall Street Journal. -

Philanthropy and the Media Guest Editor Miguel Castro, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Vol 22 Number 4 December 2017 www.alliancemagazine.org 32 Special feature Philanthropy and the media Guest editor Miguel Castro, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation 14 48 52 56 Interview: Adessium Philanthropy – the The crisis of civic media Foundation-backed Foundation media’s enlightened Bruce Sievers of Stanford journalism Founder, Gerard van Vliet despots University and Patrice Barbara Hans, editor-in-chief Schneider from the Media speaks exclusively to Alliance Gustavo Gorriti, editor of of Spiegel Online, on why it’s Development Investment IDL-Reporteros, reports best to proceed with caution Fund on new models from Peru to build trust Alliance Editorial Board Janet Mawiyoo 01 Akwasi Aidoo Kenya Community Humanity United, Development Senegal Foundation Editorial Lucy Bernholz Bhekinkosi Moyo Stanford University Southern Africa Trust, South Africa Center on Philanthropy New look and Civil Society, US Timothy Ogden AllianceThe only philanthropy magazine Philanthropy Action,US David Bonbright with a truly global focus Keystone, UK Felicitas von Peter and Michael philanthropy Carola Carazzone Alberg-Seberich Assifero, Italy Active Philanthropy, Maria Chertok Germany media CAF Russia Adam Pickering Andre Degenszajn Charities Aid Brazil Foundation, UK Vol 22 Eva Rehse Number 4 Christopher Harris December 2017 www.alliancemagazine.org AllianceFor philanthropy and social investment worldwide US Global Greengrants John Harvey Fund, Europe US Natalie Ross Charles Keidan Jenny Hodgson Council on Editor, Alliance. Foundations, US Global Fund for -

Giving Every Child a Fair Shot: Progress Under the Obama Administration’S Education Agenda

GIVING EVERY CHILD A FAIR SHOT: PROGRESS UNDER THE OBAMA ADMINISTRATION’S EDUCATION AGENDA FOREWORD When we came into office at the height of the worst recession in generations, we knew a key to creating true middle-class security would be preparing the next generation to compete in the global economy. Thanks to the hard work of our teachers, students, parents, and state and local leaders, that commitment is paying off in new opportunities for our communities and our country. Today, on National Teacher Appreciation Day, we say thank you to the leaders in our classrooms and reaffirm our shared belief that all children, no matter where they live or what they look like, can grow up to be whatever they want. A world-class education is the single most important factor in making that possible. It determines not just whether our children can compete for the best jobs, but whether America can out-compete other countries. At the beginning of my Administration, we set an ambitious goal to once again lead the world in our share of college graduates. By reforming our education system from cradle to career, and with the help of a newly announced $100 million down payment to help expand free community college programs and connect college graduates to in-demand jobs, we’re on our way to realizing that goal. We’re also proud that high school graduation rates are at an all-time high and dropout rates are at historic lows. Across the board, we’re raising expectations for everyone from the Congress to the classroom—but we didn’t stop there. -

Getting up to Your Eyeballs in Art After a Year of Sensory Deprivation, a Critic Dips a Toe Into the New, High-Powered Immersive Art Center in Miami

4 FILM REVIEW 10ART REVIEW 14TELEVISION REVIEW A supersize MoMA and Cynthia Erivo marathon for the Calder in shapely tries on Aretha Justice League. symbiosis. Franklin’s shoes. BY MAYA PHILLIPS BY ROBERTA SMITH BY JAMES PONIEWOZIK NEWS CRITICISM FRIDAY, MARCH 19, 2021 C1 N ARTHUR LUBOW CRITIC’S NOTEBOOK ALFONSO DURAN FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES TeamLab’s “Proliferating Immense Life, a Whole Year Per Year,” an interactive digital installation at Superblue in Miami, which begins previews next week. Flowers bud, grow huge and die off, accelerated by a viewer’s touch. Getting Up to Your Eyeballs in Art After a year of sensory deprivation, a critic dips a toe into the new, high-powered immersive art center in Miami. Superblue is the blue-chip contestant in the And yet they remain stuck in the gravita- FEELING A LITTLE LIKE Alice in Wonderland Superblue Miami rapidly growing field of immersive art. tional pull of virtual reality: The experi- as gigantic digital images of red, white and Opens on April 22 The popularity of this genre is driven by ences they seek are ones they can record on cream-colored dahlias budded, bloomed contradictory desires, as demonstrated their phone cameras and post on social me- and shattered on the wall in front of me, I kyo, is the dynamic centerpiece of an inau- memorably by the line of visitors in 2019 dia. dithered over what I was witnessing. Is this gural exhibition at Superblue, a Miami “ex- who waited up to six hours for a one-minute The renovated warehouse that Superblue a forward step in the march of modernism periential art center” (or EAC to initiates) stay amid the twinkling lights in Yayoi occupies in Miami is across the street from or a debasement of art into theme-park en- that begins invitational previews next week Kusama’s infinity mirror room at the David a more traditional contemporary art institu- tertainment? before opening to the public on April 22. -

The Disinformation Age

Steven Livingston W. LanceW. Bennett EDITED BY EDITED BY Downloaded from terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/1F4751119C7C4693E514C249E0F0F997THE DISINFORMATION AGE https://www.cambridge.org/core Politics, and Technology, Disruptive Communication in the United States the United in https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms . IP address: 170.106.202.126 . , on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:34:36 , subject to the Cambridge Core Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.126, on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:34:36, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/1F4751119C7C4693E514C249E0F0F997 The Disinformation Age The intentional spread of falsehoods – and attendant attacks on minorities, press freedoms, and the rule of law – challenge the basic norms and values upon which institutional legitimacy and political stability depend. How did we get here? The Disinformation Age assembles a remarkable group of historians, political scientists, and communication scholars to examine the historical and political origins of the post-fact information era, focusing on the United States but with lessons for other democracies. Bennett and Livingston frame the book by examining decades-long efforts by political and business interests to undermine authoritative institutions, including parties, elections, public agencies, science, independent journalism, and civil society groups. The other distinguished scholars explore the historical origins and workings of disinformation, along with policy challenges and the role of the legacy press in improving public communication. This title is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core. W. Lance Bennett is Professor of Political Science and Ruddick C. -

2019 ANNUAL REPORT in the Lives of Americans

2019 ANNUAL REPORT In the Lives of Americans ProPublica is an unusual news organization. Nearly all of our stories are investigative, which for most newsrooms is a small part of their work. We also have a clear mission: We seek through our journalism to spur real-world change, and we judge our own success by how often and to what extent we achieve this objective. And these are unusual times. All 2019, we want to spotlight some of interest and dividends — which of us are confronted with news those stories. describes most people. we never imagined possible, with We have been reporting about But the online services lobbied a level of polarization in our so- online tax filing services since against the idea of government-as- ciety not seen in a century and a 2013. But it was not until 2019 sisted tax prep and prevailed in ex- half, with norms being smashed that we understood the extent to change for the companies offering seemingly every week, with news which their lobbying efforts, with free services to most taxpayers. cycles shortening and attention Congress and especially the IRS, In fact, however, few taxpayers spans with them, with barriers to were resulting in higher profits used the free services. Why? Our speech dramatically lowered and for the companies. We revealed stories revealed that the free of- a resultant cacophony of speakers. that TurboTax especially, but also ferings were confusingly named How does our unusual orga- H&R Block, were selling millions (paid services were labeled “free”) nization make its way through of taxpayers a service they could and even hidden from Google and these unusual times? Sometimes, have received for free. -

Laurene-Powell-Jobs

Laurene Powell Jobs is investing in media, education, sports and more. What does she want? Laurene Powell Jobs — like the inventors and disrupters who were all around her — was thinking big. It was 2004, and she was an East Coast transplant — sprung from a cage in West Milford, N.J., as her musical idol Bruce Springsteen might put it — acclimating to the audacious sense of possibility suffusing the laboratories, garages and office parks of Silicon Valley. She could often be found at a desk in a rented office in Palo Alto, Calif., working a phone and an Apple computer. There, her own creation was beginning to take shape. It would involve philanthropy … technology … social change — she was charting the destination as she made the journey. She eventually named the project Emerson Collective after Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of her favorite writers. In time it would become perhaps the most influential product of Silicon Valley that you’ve never heard of. Yet at first, growth was slow. The work took a back seat to raising her three children and managing the care of her husband, Steve Jobs, as he battled the cancer that killed him in 2011 at age 56, followed by a period of working through family grief. She inherited his fortune, now worth something like $20 billion, and became the sixth-richest woman on the planet. By 2014, Emerson Collective was up to 10 employees. “For the first few years I worked here, there would be people who would say, ‘Who?’ ” says the eighth hire, Anne Marie Burgoyne, director of grants. -

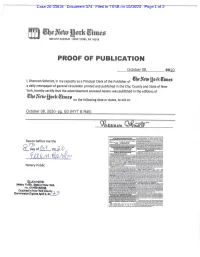

Case 20-33918 Document 374 Filed in TXSB on 10/08/20 Page 1 of 2

Case 20-33918 Document 374 Filed in TXSB on 10/08/20 Page 1 of 2 Case 20-33918 Document 374 Filed in TXSB on 10/08/20 Page 2 of 2 C M Y K Nxxx,2020-10-08,B,003,Bs-BW,E1 THE NEW YORK TIMES BUSINESS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 8, 2020 N B3 ENERGY | MEDIA | FINANCE Citing Safety, Agencies Concede Poor Planning in California Blackouts By IVAN PENN Outlet Pulls A report by California energy offi- cials on Tuesday placed blame for rolling blackouts that left millions White House without power in August on the impact of climate change and out- dated policies and practices that Reporter failed to adequately take into ac- By KATIE ROBERTSON count hotter weather. In the 121-page preliminary re- BuzzFeed News has pulled a polit- port to Gov. Gavin Newsom, the ical correspondent from the White state’s three central energy orga- House press pool, citing concerns nizations attributed the blackouts that the area has become a co- — the first in two decades — to a ronavirus hot zone after President heat wave that increased demand Trump, many of his top aides — in- for electricity while reducing the cluding the press secretary supply of power. Poor planning Kayleigh McEnany — and several compounded those problems, ac- journalists have tested positive cording to the report, which was for the virus. produced by the California Ener- A BuzzFeed News spokesman, gy Commission, the California Matt Mittenthal, confirmed that Public Utilities Commission and the company on Tuesday had the California Independent Sys- withdrawn the correspondent, tem Operator.