Inter-Ethnic Marriage Patterns in Late Sixteenth-Century Shetland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orkney and Shetland

History, Heritage and Archaeology Orkney and Shetland search Treasures from St Ninian’s Isle, Shetland search St Magnus Cathedral, Orkney search Shetland fiddling traditions search The Old Man of Hoy, Orkney From the remains of our earliest settlements going back Ring of Brodgar which experts estimate may have taken more thousands of years, through the turbulent times of the than 80,000 man-hours to construct. Not to be missed is the Middle Ages and on to the Scottish Enlightenment and fascinating Skara Brae - a cluster of eight houses making up the Industrial Revolution, every area of Scotland has its Northern Europe’s best-preserved Neolithic village. own tale to share with visitors. You’ll also find evidence of more recent history to enjoy, such The Orkney islands have a magical quality and are rich in as Barony Mill, a 19th century mill which produced grain for history. Here, you can travel back in time 6,000 years and Orkney residents, and the Italian Chapel, a beautiful place of explore Neolithic Orkney. There are mysterious stone circles worship built by Italian prisoners of war during WWII. to explore such as the Standing Stones of Stenness, and the The Shetland Islands have a distinctive charm and rich history, and are littered with intriguing ancient sites. Jarlshof Prehistoric and Norse Settlement is one of the most Events important and inspirational archaeological sites in Scotland, january Up Helly Aa while 2,000 year old Mousa Broch is recognised as one of www.uphellyaa.org Europe’s archaeological marvels. The story of the internationally famous Shetland knitting, Orkney Folk Festival M ay with its intricate patterns, rich colours and distinctive yarn www.orkneyfolkfestival.com spun from the wool of the hardy breed of sheep reared on the islands, can be uncovered at the Shetland Textile Museum. -

Orkney & Shetland

r’ Soil Survey of Scotland ORKNEY & SHETLAND 1250 000 SHEET I The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research Aberdeen 1982 SOIL SURVEY OF SCOTLAND Soil and Land Capability for Agriculture ORKNEY AND SHETLAND By F. T. Dry, BSc and J. S. Robertson, BSc The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research Aberdeen 1982 @ The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research, Aberdeen, 1982 The cover illustration shows St. Magnus Bay, Shetland with Foula (centre nght) in the distance. Institute of Geological Sciences photograph published by permission of the Director; NERC copyright. ISBN 0 7084 0219 4 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS ABERDEEN Contents Chapter Page PREFACE 1 DESCRIPTIONOF THE AREA 1 GEOLOGY AND RELIEF 1 North-east Caithness and Orkney 1 Shetland 3 CLIMATE 9, SOILS 12 North-east Caithness and Orkney 12 Shetland 13 VEGETATION 14 North-east Caithness and Orkney 14 Shetland 16 LAND USE 19 North-east Caithness and Orkney 19 Shetland 20 2 THE SOIL MAP UNITS 21 Alluvial soils 21 Organic soils 22 The Arkaig Association 24 The Canisbay Association 29 The Countesswells/Dalbeattie/Priestlaw Associations 31 The Darleith/Kirktonmoor Associations 34 The Deecastle Association 35 The Dunnet Association 36 The Durnhill Association 38 The Foudland Association 39 The Fraserburgh Association 40 The Insch Association 41 The Leslie Association 43 The Links Association 46 The Lynedardy Association 47 The Rackwick Association 48 The Skelberry Association 48 ... 111 CONTENTS The Sourhope Association 50 The Strichen Association 50 The Thurso Association 52 The Walls -

The Social Context of Norse Jarlshof Marcie Anne Kimball Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2003 The social context of Norse Jarlshof Marcie Anne Kimball Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Kimball, Marcie Anne, "The ocs ial context of Norse Jarlshof" (2003). LSU Master's Theses. 2426. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2426 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SOCIAL CONTEXT OF NORSE JARLSHOF A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and the Arts and Science College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Marcie Anne Kimball B.S., Northwestern State University of Louisiana, 2000 August 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author is grateful to her major professor Dr. Rebecca Saunders, Associate Professor of Anthropology, and her thesis committee members Dr. Paul Farnsworth, Associate Professor of Anthropology, and Dr. Miles Richardson, Professor of Anthropology, all of Louisiana State University. The author is also grateful to Dr. Gerald Bigelow, Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Southern Maine, and to Mr. Stephen Dockrill, Director of Old Scatness Excavations, and to Dr. Julie Bond, Assistant Director of Old Scatness Excavations, for their guidance and assistance. -

Review Articles

REVIEW ARTICLES John Stewart: Shetland Place-names. Shetland Library and Museum, Lerwick, 1987. 354 pp. John Stewart was born in Whalsay in Shetland in 1903. He was educated at Brough School in Whalsay, the Anderson Educational Institute in Lerwick and Aberdeen University. His working life was spent teaching in Aberdeen but his leisure time was devoted to the study of the languages and history of Shetland and in 1950 he embarked on the ambitious project of recording all Shetland place names. With the assistance of the schoolchildren of the islands he assembled a vast body of material, which'he supplemented by his 'own work in the field and in archives. His original intent had been to register all the names but .he found it advisable to concentrate first on producing a comprehensive study of the island- and farm-names. He plotted all names on maps and recorded their Grid reference, collected early written forms and noted the pronunciation in phonetic symbols. The names and the elements they contained were compared with place-name material from Norway, Faroe, Iceland, Orkney and northern Scotland. A general introduction to the collection, entitled "Shetland Farm Names", was presented to the fourth Viking Congress in York in 1961 and published by the University ofAberdeen in 1965 in the Congress proceedings. Unfortunately, John Stewart died in 1977 before he had been able to publish the material on which his lecture had been based. Generously, the Shetland Island Council agreed to finance the present publication and its preparation for the press was entrusted to Brian Smith. John Stewart's typescript has been published as he left it, except that the format of the entries has been regularised and information about the markland values omitted. -

The Coastal Landslides of Shetland

The coastal landslides of Shetland Colin K. Ballantyne, Sue Dawson, Ryan Dick, Derek Fabel, Emilija Kralikaite, Fraser Milne, Graeme F. Sandeman, and Sheng Xu Date of deposit 18 04 2018 Document version Author’s accepted manuscript Access rights © 2018 Royal Scottish Geographical Society. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. This is the author created, accepted version manuscript following peer review and may differ slightly from the final published version. Citation for Ballantyne, C. K., Dawson, S., Dick, R., Fabel, D., Kralikaite, E., published version Milne, F., Sandeman, G. F., and Xu, S. (2018). The coastal landslides of Shetland. Scottish Geographical Journal, Latest Articles. Link to published https://doi.org/10.1080/14702541.2018.1457169 version Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Page 1 of 40 Scottish Geographical Journal 1 2 3 The coastal landslides of Shetland 4 5 6 7 ABSTRACT Little is known of hard-rock coastal landsliding in Scotland. We identify 128 8 9 individual coastal landslides or landslide complexes >50 m wide along the coasts of Shetland. 10 11 Most are apparently translational slides characterized by headscarps, displaced blocks and/or 12 debris runout, but 13 deep-seated failures with tension cracks up to 200 m inland from cliff 13 14 crests were also identified. 31 sites exhibit evidence of at least localized recent activity. 15 Landslide distribution is primarily determined by the distribution of coastal cliffs >30 m high, 16 For Peer Review Only 17 and they are preferentially developed on metasedimentary rocks. -

NSA Special Qualities

Extract from: Scottish Natural Heritage (2010). The special qualities of the National Scenic Areas . SNH Commissioned Report No.374. The Special Qualities of the Shetland National Scenic Area Shetland has an outstanding coastline. The seven designated areas that make-up the NSA comprise Shetland’s scenic highlights and epitomise the range of coastal forms varying across the island group. Some special qualities are generic to all the identified NSA areas, others are specific to each area within the NSA. The seven individual areas of the NSA are : Fair Isle, South West Mainland, Foula, Muckle Roe, Eshaness, Fethaland , and Hermaness . Where a quality applies to a particular area, the name is highlighted in bold . • The stunning variety of the extensive coastline • Coastal views both close and distant • Coastal settlement and fertility within a large hinterland of unsettled moorland and coast • The hidden coasts • The effects and co-existence of wind and shelter • A sense of remoteness, solitude and tranquillity • The notable and memorable coastal stacks, promontories and cliffs • The distinctive cultural landmarks • Northern light Special Quality Further information • The stunning variety of the extensive coastline Shetland’s long, extensive coastline is South West Mainland , stretching from Fitful Head (Old highly varied: from fissured and Norse hvitfugla, white birds) to the Deeps, displays greatly contrasting coastlines: fragmented hard rock coasts, to gentler formations of accumulated gravels, • Cliffed coastline of open aspect in the south to long voes sands, spits and bars; from remarkably at Weisdale and Whiteness. • Numerous small islands and stacks, notably in the area steep cliffs to sloping bays; from long, west of Scalloway. -

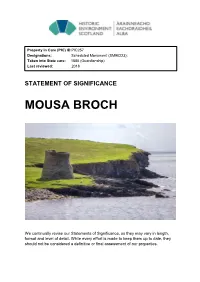

Mousa Broch Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID:PIC257 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90223); Taken into State care: 1885 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2018 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE MOUSA BROCH We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE MOUSA BROCH CONTENTS 1 Summary 2 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Statement of significance 2 2 Assessment of values 3 2.1 Background 3 2.2 Evidential values 6 2.3 Historical values 8 2.4 Architectural and artistic values 12 2.5 Landscape and aesthetic values 15 2.6 Natural heritage values 16 2.7 Contemporary/use values 17 3 Major gaps in understanding 18 4 Associated properties 23 5 Keywords 23 Bibliography 24 APPENDICES Appendix 1: Timeline 30 Appendix 2: Images 32 Appendix 3: Mousa Broch,detailed description 42 Appendix 4: Brochs – theories and interpretations 49 Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. -

Our New E-Commerce Enabled Shop Website Is Still Under Construction

Our new e-commerce enabled shop website is still under construction. In the meantime, to order any title listed in this booklist please email requirements to [email protected] or tel. +44(0)1595 695531 2009Page 2 The Shetland Times Bookshop Page 2009 2 CONTENTS About us! ..................................................................................................... 2 Shetland – General ...................................................................................... 3 Shetland – Knitting .................................................................................... 14 Shetland – Music ........................................................................................ 15 Shetland – Nature ...................................................................................... 16 Shetland – Nautical .................................................................................... 17 Children – Shetland/Scotland..................................................................... 18 Orkney – Mackay Brown .......................................................................... 20 Orkney ...................................................................................................... 20 Scottish A-Z ............................................................................................... 21 Shetland – Viking & Picts ........................................................................... 22 Shetland Maps .......................................................................................... -

Books from Shetland

2009 The Shetland Times Bookshop Page 1 CONTENTS About us! ..................................................................................................... 2 Shetland – General ...................................................................................... 3 Shetland – Knitting .................................................................................... 14 Shetland – Music ........................................................................................ 15 Shetland – Nature ...................................................................................... 16 Shetland – Nautical .................................................................................... 17 Children – Shetland/Scotland..................................................................... 18 Orkney – Mackay Brown .......................................................................... 20 Orkney ...................................................................................................... 20 Scottish A-Z ............................................................................................... 21 Shetland – Viking & Picts ........................................................................... 22 Shetland Maps ........................................................................................... 23 Shetland/Orkney Videos/DVDs................................................................. 24 Shetland – CDs/Cassettes ......................................................................... 24 Orkney – CDs .......................................................................................... -

Jarlshof Audio Guide Text Transcript

Jarlshof large print audio guide script 1 Welcome Narrator: Hello and welcome to Jarlshof. Today, you’re going to discover one of the most fascinating archaeological sites here on the Shetland Islands or, indeed, in the UK. You should now be standing outside the visitor centre, from where you have a good view of the site in front of you. About a hundred years ago, all you would have seen from this spot would have been a grassy mound with just one ruin, the tallest building just ahead of you. But that all changed on a stormy night in the late eighteen hundreds when fierce winds battered the island. Remains of earlier buildings were exposed, and the landowner of the site, John Bruce, started to dig. He found a number of structures that were later confirmed to be pre-historic. In 1925 he gave the site to the government, who, through Historic Scotland, still care for it today. Their excavations revealed the whole extent of this site. Today, you’re going to take a journey through 4000 years of human history. We’ll be looking at the remains chronologically. All you’ll need to do is follow the directions at the end of each stop. Now and again, you’ll also have the possibility to access additional information. If you listen to everything, your visit will last about an hour. You can pause a commentary at any time by pressing the red button. It will resume if you press the green button. The volume controls are marked with a loudspeaker symbol. -

The Last Glaciation of Shetland: Local Ice Cap Or Invasive Ice Sheet? 229

NORWEGIAN JOURNAL OF GEOLOGY The last glaciation of Shetland: local ice cap or invasive ice sheet? 229 The last glaciation of Shetland: local ice cap or invasive ice sheet? Adrian M. Hall Hall, A.M.: The last glaciation of Shetland: local ice cap or invasive ice sheet? Norwegian Journal of Geology , Vol 93, pp. 229–242. Trondheim 2013, ISSN 029-196X. The question of whether the Shetland Islands were covered by an ice cap or by an ice sheet during the last glacial cycle (40–10 ka) remains unresolved. This paper addresses this problem using existing and new data on glacial erratic carry, striae, glacial lineaments and roche moutonnée asymmetry. Its focus is on eastern Shetland, where ice-cap and ice-sheet glaciation would lead to opposed ice-flow directions, towards and away from the North Sea. Evidence cited in support of ice-sheet glaciation of Shetland is questioned. The primary survey of striae correctly identified striae orientation but the direction of ice flow from striae on eastern Shetland was misinterpreted: it was not from, but towards the North Sea. Glacial lineaments interpolated to cross the spine of Shetland instead are discontinuous and diverge away from an axial ice-shed zone that lacks lineaments. Glacitectonic structures cited recently as evidence for westward flow of an ice sheet across eastern Shetland have been partly mis- interpreted and other ice-flow indicators in the vicinity of key sites indicate former eastward ice flow towards the North Sea. Westward carry of erratics over short distances in N and S Shetland may be partly accounted for by shifts in ice sheds during ice-cap deglaciation. -

Stuart Hill Dissects Shetland’S History and Reveals a New Interpretation of Its Constitutional Position

Stuart Hill dissects Shetland’s history and reveals a new interpretation of its constitutional position. FORVIK Working from the legally accepted position that the relationship between Shetland and the United Kingdom is based on the 1469 pawning document, he analyses what that document meant at the time and then traces the actions of the Scottish and UK Crowns in connection with it. What he uncovers is a world of intrigue and double dealing, with the rights and concerns of Shetland people ignored for the benefit of powerful outside interests. He concludes that such has been the magnitude of that abuse that it leaves the people of Shetland in a powerful position if they ever wanted to assert their ancient rights. Includes previously unknown documents, others apparently considered too sensitive for public consumption and a fresh interpretation of existing historical sources. Stuart Hill FORVIK An examination of the source of the UK government’s authority in Shetland. Stuart Hill Forvik, published 2009 by Stuart Hill Steward’s Residence Forvik Shetland ZE2 9PL © Stuart Hill 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the author. ISBN Printed by Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Background 3 3. The Pawning 4 4. 1472 6 5. Sovereignty 8 6. 1469 -1667 11 7. The Treaty of Breda 1667 13 8. 1669 Act of Annexation 14 8. The Act of Union 17 9. After the Union 18 10. The Crown Estates 19 11.