On History, Takings Jurisprudence, and Palazzolo: a Reply to James Burling Timothy J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arsenal of Megadeth Mp3, Flac, Wma

Megadeth Arsenal Of Megadeth mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Non Music Album: Arsenal Of Megadeth Country: Russia Released: 2006 Style: Interview, Speed Metal, Thrash, Heavy Metal MP3 version RAR size: 1329 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1871 mb WMA version RAR size: 1317 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 535 Other Formats: AU MP4 AHX VOC APE DTS DMF Tracklist Hide Credits 1.1 Film Excerpt From The Movie Talk Radio 0:35 1.2 Peace Sells (Video) 4:16 1.3 Megadeth Interview, 1986 2:31 1.4 Wake Up Dead (Video) 4:05 1.5 Cutting Edge Happy Hour Interview Intro 0:22 In My Darkest Hour (From: The Decline Of Western Civilization Part II: The Metal Years) 1.6 5:10 (Video) 1.7 So Far, So Good... So What! Album Interview Excerpts 2:49 1.8 Anarchy In The U.K (Video) 3:01 1.9 No More Mr. Nice Guy (Video) 3:02 1.10 Marty Friedman Unreleased Audition Footage (Easter Egg) 3:58 1.11 Rust In Peace Album Release TV Spot 0:37 1.12 Clash Of The Titans Tour Footage, 1990 6:49 1.13 Holy Wars... The Punishment Due (Video) 6:35 1.14 Mission Megadeth: Headbanger's Ball (Excerpts From 5/18/91 Broadcast Show) 2:53 1.15 Hangar 18 (Longform Unedited Version) (Video) 6:27 1.16 Go To Hell (Guitar Version) (Video) 4:34 1.17 Rock The Vote Clip 1 (Megadeth) 0:30 1.18 Rock The Vote Clip 2 (Dave Mustaine) 0:14 1.19 Rock The Vote Clip 3 (Dave Mustaine) 0:16 1.20 Countdown To Extinction Album Release TV Spot 0:37 1.21 Symphony Of Destruction (Video) 4:11 Symphony Of Destruction (The Gristle Mix) (Video Edit) (Easter Egg) 1.22 3:49 Remix – Trent Reznor 1.23 Skin O' My -

Megadeth Arsenal of Megadeth Mp3, Flac, Wma

Megadeth Arsenal Of Megadeth mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Non Music Album: Arsenal Of Megadeth Country: US Released: 2006 Style: Interview, Public Service Announcement, Speed Metal, Thrash, Heavy Metal MP3 version RAR size: 1961 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1432 mb WMA version RAR size: 1613 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 302 Other Formats: WMA MPC DMF AA DTS AIFF MOD Tracklist Hide Credits DVD1.1 Film Excerpt From The Movie Talk Radio 0:35 DVD1.2 Peace Sells (Video) 4:16 DVD1.3 Megadeth Interview, 1986 2:31 DVD1.4 Wake Up Dead (Video) 4:05 DVD1.5 Cutting Edge Happy Hour Interview Intro 0:22 In My Darkest Hour (From: The Decline Of Western Civilization Part II: The Metal DVD1.6 5:10 Years) (Video) DVD1.7 So Far, So Good... So What! Album Interview Excerpts 2:49 DVD1.8 Anarchy In The U.K (Video) 3:01 DVD1.9 No More Mr. Nice Guy (Video) 3:02 DVD1.10 Marty Friedman Unreleased Audition Footage (Easter Egg) 3:58 DVD1.11 Rust In Peace Album Release TV Spot 0:37 DVD1.12 Clash Of The Titans Tour Footage, 1990 6:49 DVD1.13 Holy Wars... The Punishment Due (Video) 6:35 DVD1.14 Mission Megadeth: Headbanger's Ball (Excerpts From 5/18/91 Broadcast Show) 2:53 DVD1.15 Hangar 18 (Longform Unedited Version) (Video) 6:27 DVD1.16 Go To Hell (Guitar Version) (Video) 4:34 DVD1.17 Rock The Vote Clip 1 (Megadeth) 0:30 DVD1.18 Rock The Vote Clip 2 (Dave Mustaine) 0:14 DVD1.19 Rock The Vote Clip 3 (Dave Mustaine) 0:16 DVD1.20 Countdown To Extinction Album Release TV Spot 0:37 DVD1.21 Symphony Of Destruction (Video) 4:11 Symphony Of Destruction (The -

Hal Leonard Bass Play-Along) Online

ciBr0 (Download free pdf) Megadeth: Bass Play-Along Volume 44 (Hal Leonard Bass Play-Along) Online [ciBr0.ebook] Megadeth: Bass Play-Along Volume 44 (Hal Leonard Bass Play-Along) Pdf Free Megadeth ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #2550247 in Books Hal Leonard 2014-07-01Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 12.00 x .23 x 9.00l, .0 #File Name: 145842362X64 pages | File size: 20.Mb Megadeth : Megadeth: Bass Play-Along Volume 44 (Hal Leonard Bass Play-Along) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Megadeth: Bass Play-Along Volume 44 (Hal Leonard Bass Play-Along): 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Four StarsBy Stanley Cup BrianI like it. (Bass Play-Along). The Bass Play-Along Series will help you play your favorite songs quickly and easily! Just follow the tab, listen to the CD to hear how the bass should sound, and then play along using the separate backing tracks. The melody and lyrics are also included in the book in case you want to sing, or to simply help you follow along. The audio CD is playable on any CD player. For PC and Mac computer users, the CD is enhanced so you can adjust the recording to any tempo without changing pitch! This volume includes: Hangar 18 * Head Crusher * Holy Wars...The Punishment Due * Peace Sells * Sweating Bullets * Symphony of Destruction * Train of Consequences * Trust. [ciBr0.ebook] Megadeth: Bass Play-Along Volume 44 (Hal Leonard Bass Play-Along) By Megadeth PDF [ciBr0.ebook] Megadeth: Bass Play-Along Volume 44 (Hal Leonard Bass Play-Along) By Megadeth Epub [ciBr0.ebook] Megadeth: Bass Play-Along Volume 44 (Hal Leonard Bass Play-Along) By Megadeth Ebook [ciBr0.ebook] Megadeth: Bass Play-Along Volume 44 (Hal Leonard Bass Play-Along) By Megadeth Rar [ciBr0.ebook] Megadeth: Bass Play-Along Volume 44 (Hal Leonard Bass Play-Along) By Megadeth Zip [ciBr0.ebook] Megadeth: Bass Play-Along Volume 44 (Hal Leonard Bass Play-Along) By Megadeth Read Online. -

The Cathedral and the Bazaar

,title.21657 Page i Friday, December 22, 2000 5:39 PM The Cathedral and the Bazaar Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary ,title.21657 Page ii Friday, December 22, 2000 5:39 PM ,title.21657 Page iii Friday, December 22, 2000 5:39 PM The Cathedral and the Bazaar Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary Eric S. Raymond with a foreword by Bob Young BEIJING • CAMBRIDGE • FARNHAM • KÖLN • PARIS • SEBASTOPOL • TAIPEI • TOKYO ,copyright.21302 Page iv Friday, December 22, 2000 5:38 PM The Cathedral and the Bazaar: Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary, Revised Edition by Eric S. Raymond Copyright © 1999, 2001 by Eric S. Raymond. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly & Associates, Inc., 101 Morris Street, Sebastopol, CA 95472. Editor: Tim O’Reilly Production Editor: Sarah Jane Shangraw Cover Art Director/Designer: Edie Freedman Interior Designers: Edie Freedman, David Futato, and Melanie Wang Printing History: October 1999: First Edition January 2001: Revised Edition This material may be distributed only subject to the terms and conditions set forth in the Open Publication License, v1.0 or later. (The latest version is presently available at http://www.opencontent.org/openpub/.) Distribution of substantively modified versions of this document is prohibited without the explicit permission of the copyright holder. Distribution of the work or derivatives of the work in any standard (paper) book form is prohibited unless prior permission is obtained from the copyright holder. The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly & Associates, Inc. -

184:46:49 Total Tracks Size: 24.6 GB

Total tracks number: 2615 Total tracks length: 184:46:49 Total tracks size: 24.6 GB # Artist Title Length 01 3 Doors Down Believe It 03:22 02 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:57 03 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:55 04 3 Doors Down Landing in London 04:31 05 3 Doors Down When i"m gone 04:20 06 4 Non Blondes What's Up? 04:55 07 4 The Cause Stand By Me 03:43 08 10cc The Things We Do For Love 03:28 09 38 Special Caught Up In You 04:31 10 38 Special Fantasy Girl 03:59 11 38 Special Hold On Loosely 04:33 12 38 Special Teacher Teacher 03:11 13 38 Special Wild - Eyed Southern Boys (1) 04:07 14 A Perfect Circle Disillusioned 05:53 15 Accept Balls To The Walls 05:41 16 Accept Breaking Up Again 04:33 17 AC-DC Are You Ready 04:10 18 AC-DC Back In Black 04:11 19 AC-DC Bad Boy Boogie 04:25 20 AC-DC Big Balls 02:38 21 AC-DC Big Gun 04:21 22 AC-DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 04:10 23 AC-DC Down Payment Blues 06:00 24 AC-DC For Those About To Rock 05:43 25 AC-DC Girls Got Rhythm 03:21 26 AC-DC Givin The Dog A Bone 03:32 27 AC-DC Hard As A Rock 04:28 28 AC-DC Have A Drink On Me 03:59 29 AC-DC Hells Bells 05:11 30 AC-DC High Voltage 03:58 31 AC-DC Highway To Hell 03:27 32 AC-DC If You Want Blood (You've Got It) 04:31 33 AC-DC It's A Long Way To The Top (If You Wanna Rock 'N' Roll) 05:00 34 AC-DC I've Got Big Balls 02:37 35 AC-DC Jailbreak 04:35 36 AC-DC Let There Be Rock 06:05 37 AC-DC Live Wire 05:43 38 AC-DC Love Hungry Man 04:14 39 AC-DC Moneytalks 03:43 40 AC-DC Night Prowler 06:13 41 AC-DC Problem Child 05:43 42 AC-DC Ride On 05:48 43 AC-DC Rock And Roll -

Megadeth Live Free Download Dvd Torrent Free Megadeth Download

megadeth live free download dvd torrent Free Megadeth download. Thrashers Megadeth will be giving away a free download of a track from their new album today. So that’s nice. ‘Headcrusher’ will go online at www.roadrunnerrecords.co.uk from 4pm and will be available for 24hrs only. Says frontman Dave Mustaine of the new album, ‘Endgame’: “This new album is my proudest moment since the famous (or infamous) ‘Rust In Peace’ album. With this album I am also very excited to be introducing my new lead guitarist Chris Broderick to the world. I have always felt lucky to have had top shredders in that position but after touring with Chris in support of my last album, I couldn’t wait to get into the studio and see what he could do”. You can kind out just how good Chris is at shredding when the band tour the UK next year. Or even sooner than that, as the album will be released via Roadrunner Records on 14 Sep. Look, here’s a tracklist to prove its existence: Dialectic Chaos This Day We Fight! 44 Minutes 1,320 Bite The Hand That Feeds Bodies Left Behind Endgame The Hardest Part Of Letting Go… Sealed With A Kiss Headcrusher How the Story Ends Nothing Left To Lose. Megadeth live free download dvd torrent. Megadeth - Discography (1985-2016) Country: USA Genre: Speed/Thrash/Heavy Metal Quality: Mp3, CBR 320 kbps (CD Rip+Scans) 1 Last Rites / Loved To Deth 4:41 2 Killing Is My Business. And Business Is Good! 3:07 3 The Skull Beneath The Skin 3:48 4 Rattlehead 3:43 5 Chosen Ones 2:55 6 Looking Down The Cross 5:02 7 Mechanix 4:25 8 These Boots 4:39 Bonus Tracks 9 Last Rites / Loved To Deth (Demo) 4:16 10 Mechanix (Demo) 3:59 11 The Skull Beneath The Skin (Demo) 3:11. -

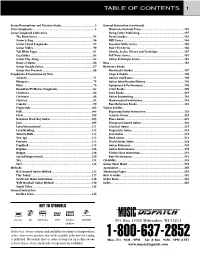

Table of Contents 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Series Descriptions and Notation Guide.........................................2 General Instruction (continued) Artist Songbooks............................................................................4 Musicians Institute Press.....................................................152 Guitar Songbook Collections String Letter Publishing.......................................................157 The Book Series ....................................................................54 Pocket Guides......................................................................162 Strum & Sing .........................................................................56 REH Series ..........................................................................164 Guitar Chord Songbooks .......................................................57 Essential Skills Series .........................................................166 Guitar Bibles .........................................................................59 Don’t Fret Series .................................................................166 Tab White Pages ....................................................................61 Chords, Scales, Theory and Technique ................................167 Gig Guides.............................................................................62 Riff Notes Series..................................................................181 Guitar Play-Along ..................................................................64 Guitar Technique Series -

Megadeth Collection 3

CCCOLLECTIONCOLLECTION 200 CCCDCDD’’’’SSSS,,,, IIIMPORTIMPORTMPORT,, PROMO, SINGLESSINGLES,, BOX… JAPAN IMPORT / PROMO SAMPLER (3(33333)))) Killing is my business …And business is good! 1985 CBS/ Sony records/Combat 25 DP 5343 8 Tracks Japan booklet (Out of print) Killing is my business…And business is good! (SAMPLE NOT FOR SALE) 1985 Sony records/Combat SRCS 7549 7 Tracks (these boots missing) Japan booklet(out of print) Killing is my business …And business is good! (Remasters) (SAMPLE LOANED) 2002 Sony records SICP 93 11 Tracks Japan booklet (3 bonus tracks) Peace sells … But who’s buying? 1986 Capitol records/ Combat CP32-5400 8 Tracks Japan booklet (Out of print, very hard to find) Peace sells … But who’s buying? (SAMPLE NOT FOR SALE) 1990 Capitol records TOCP-6537 8 Tracks Japan booklet (Out of print, very hard to find) So far, so good … so what! 1989 Capitol records/ Combat CP32-5579 8 Tracks Japan booklet (Out of print, very hard to find) So far, so good … so what! (SAMPLE NOT FOR SALE) 1991 Capitol records TOCP-6752 8 Tracks Japan booklet (Out of print, very hard to find) So far, so good … so what! (SAMPLE NOT FOR SALE) 1995 Capitol records TOCP-63028 8 Tracks Japan booklet (Out of print, very hard to find) Rust In Peace (SAMPLE NOT FOR SALE) 1990 Capitol records/ Combat TOCP-6252 9 tracks Japan booklet (Out of print, very hard to find) Hangar 18 (SAMPLE NOT FOR SALE) 1990 Capitol records TOCP-6667 5 Tracks Japan booklet (Out of print, very hard to find) Countdown to extinction (SAMPLE NOT FOR SALE) 1992 Capitol records TOCP-7164 -

Top 1000 Classic Rock Torrent Download (0751 - 1000) Album

top 1000 classic rock torrent download (0751 - 1000) Album. Top 1000 of the Millennium Size. 1,51 Gb Source. CDDA Playtime.: 19:33:05 (h:min:sec) Genre. Billboard, Heavy Metal, Hard Rock Date. 1980,1972,1983,1981,2000,2003,1991,1990 2001,1997,1973,1996,2002,1988,1984,2004, 1995,1994,1975,1989,1971,1976,1992,1993, 1979,1987,2005,1998,1968,1999,1974,1969, 1985,1970,1982,1967,1986,1978 Release. Sep-23-2009 // 001-250 Encoder. LAME V3.98r -V2 --Vbr-New Quality. VBRkbps 44,1Hz Joint-Stereo. 751.Stabbing Westward-What Do I Have To Do 752.ACDC-1979-Highway To Hell-09-Love Hungry Man 753.The Rolling Stones-1970-Get Yer Ya-Ya's Out!-10-Street Fighting Man 754.Scorpions-1982-Blackout-08-China White 755.Heart-1977-Little Queen-02-Love Alive 756.Pink Floyd-Pigs (Three Different Ones) 757.Chris Cornell-Sunshower 758.Bad Company-1976-Run With The Pack-06-Silver, Blue & Gold 759.Rush-1990-Chronicles-23-The Big Money 760.top_500_rock_and_roll_songs-270-the_who-eminence_front. 761.Billboard_Top_100_Hits_Of_1995_-_041_-_COLLECTIVE_SOUL_-_December 762.Van Halen-Secrets 763.Green Day-1997- Nimrod-17-Good Riddance (Time of Your Life) 764.Fleetwood Mac-1988-Then Play on-06-Oh Well 765.Kiss-1982-Killers-10-God Of Thunder 766.Pat Travers-Boom Boom (Out Go The Lights) 767.Aerosmith-1989-Pump-10-What It Takes 768.Boston-1997-Greatest Hits-04- Peace of Mind 769.Pat Benatar-Hell Is For Children 770.Ozzy Osbourne-2002-No Rest For The Wicked-01-Miracle Man. -

10 Years Battle Lust Now Is the Time (Ravenous)

10 Years Ace Frehley Battle Lust Outer Space Now Is The Time (Ravenous) Shoot It Out The Acro-brats Day Late, Dollar Short 3 Doors Down Here Without You Aerosmith It's Not My Time Back in the Saddle Kryptonite Cryin' When I'm Gone Dream On When You're Young Dream On (Live) I Don't Want to Miss a Thing 30 Seconds to Mars Legendary Child Attack Love In An Elevator Closer to the Edge Lover Alot From Yesterday Sweet Emotion Kings and Queens Train Kept A Rollin' The Kill Uncle Salty This Is War Walk This Way Woman of the World 311 Amber AFI Beautiful Disaster Beautiful Thieves Down Dancing Through Sunday End Transmission 38 Special Girl's Not Grey Caught Up In You Love Like Winter Hold On Loosely Medicate Miss Murder 4 Non Blondes The Leaving Song, Pt. II What's Up The Missing Frame a-ha After the Burial Take on Me Aspiration Berzerker ABBA Cursing Akhenaten Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midni... My Frailty Pendulum Abnormality Your Troubles Will Cease and Fortune Wi... Visions Against Me! AC/DC New Wave Back in Black (Live) Stop! Big Gun Thrash Unreal Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) Fire Your Guns (Live) Airbourne For Those About to Rock (We Salute You)... Runnin' Wild Heatseeker (Live) Too Much, Too Young, Too Fast Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) Hells Bells (Live) Alanis Morissette High Voltage (Live) Head Over Feet Highway to Hell (Live) Ironic Jailbreak (Live) You Oughta Know Let Me Put My Love Into You Let There Be Rock (Live) Alice Cooper Moneytalks (Live) Billion Dollar Babies (Live) Shoot to Thrill (Live) Elected T.N.T. -

CATALOG Guitar Popular

Sheet Music Online Ordering Instructions PDF File Guitar/Tab Comprehensive Listing Sheet Music Online Problems, Questions? 5830 S.E. Sky High Ct. Contact: Milwaukie, OR 97267 Dr. Rein P. Vaga, D.M.A. 503-794-9696 [email protected] http://www.sheetmusic1.com Online since 1995!! You should be viewing this file with version 4.x of Acrobat Reader. Contents of this document is too large for a single web page, so I am trying this format. - R. Vaga How to use this PDF file • Click on "Navigation Pane" to show contents list (should be next to printer icon). • Scroll contents list, click on any title, which will take you to the entry with complete contents list. • For "search" function (song title, artist, etc.), click on the binoculars (Find button) • Mess around a bit. Acrobat Reader has lots of helpful functions! --- Ordering Instructions Next Page --- To order: 1. Return to the page where you downloaded the file you're reading: https://ssl.sheetmusic1.com/smssl/guitar.html or http://www.sheetmusic1.com/guitar.html You may also call the above listed telephone order office hours west coast time zone --- Delivery Charge --- $4.95 any number of collections in one mailing International Orders Air Mail: Your email confirmation will list the cheapest air and surface rates possible. Your card will not be charged until you confirm your order via email. If you have the time, even if you do not order. Send me an email and let me know how this format (downloadable PDF file) works for you. As a download, it should be fairly quick for everyone.