The Cathedral and the Bazaar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cathedral and the Bazaar Eric Steven Raymond Thyrsus Enterprises [

The Cathedral and the Bazaar Eric Steven Raymond Thyrsus Enterprises [http://www.tuxedo.org/~esr/] <[email protected]> This is version 3.0 Copyright © 2000 Eric S. Raymond Copyright Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the Open Publication License, version 2.0. $Date: 2002/08/02 09:02:14 $ Revision History Revision1.57 11September2000 esr New major section “How Many Eyeballs Tame Complexity”. Revision1.52 28August2000 esr MATLAB is a reinforcing parallel to Emacs. Corbatoó & Vyssotsky got it in 1965. Revision1.51 24August2000 esr First DocBook version. Minor updates to Fall 2000 on the time-sensitive material. Revision1.49 5May2000 esr Added the HBS note on deadlines and scheduling. Revision1.51 31August1999 esr This the version that O’Reilly printed in the first edition of the book. Revision1.45 8August1999 esr Added the endnotes on the Snafu Principle, (pre)historical examples of bazaar development, and originality in the bazaar. Revision 1.44 29 July 1999 esr Added the “On Management and the Maginot Line” section, some insights about the usefulness of bazaars for exploring design space, and substantially improved the Epilog. Revision1.40 20Nov1998 esr Added a correction of Brooks based on the Halloween Documents. Revision 1.39 28 July 1998 esr I removed Paul Eggert’s ’graph on GPL vs. bazaar in response to cogent aguments from RMS on Revision1.31 February101998 esr Added “Epilog: Netscape Embraces the Bazaar!” Revision1.29 February91998 esr Changed “free software” to “open source”. Revision1.27 18November1997 esr Added the Perl Conference anecdote. Revision 1.20 7 July 1997 esr Added the bibliography. -

Broken Breakout Promises

Broken Breakout Promises Broken Breakout Promises Before co-founding Apple in April 1976, Steve Jobs was one of the To make ends meet in the summer of first 50 employees at Atari, the legendary Silicon Valley game company 1972, Woz, Jobs, and Jobs’ girlfriend took $3-per-hour jobs at the Westgate founded by Nolan Kay Bushnell in 1972. Atari’s Pong, a simple Mall in San Jose, California, dressing up electronic version of ping-pong, had caught on like wildfire in arcades as Alice In Wonderland characters. Jobs and homes across the country, and Bushnell was anxious to come up and Woz alternated as the White Rabbit with a successor. He envisioned a variation on Pong called Breakout, and the Mad Hatter. in which the player bounced a ball off a paddle at the bottom of the screen in an attempt to smash the bricks in a wall at the top. Bushnell turned to Jobs, a technician, to design the circuitry. Initially Jobs tried to do the work himself, but soon realized he was in way over his head and asked his friend Steve Wozniak to bail him out. “Steve wasn’t capable of designing anything that complex. He came .atarihq.com) “He was the only person I met who knew more about electronics than me.” Courtesy of Atari Gaming Headquarters (www Courtesy of Steve Jobs, explaining his initial fascination with Woz “Steve didn’t know very much about electronics.” Conceived by Bushnell, Breakout was originally designed by Wozniak and Jobs. Steve Wozniak For more info, or to order a copy, please visit http://www.netcom.com/~owenink/confidential.html 17 Broken Breakout Promises to me and said Atari would like a game and described how it would work,” recalls Wozniak. -

How to Ask Questions the Smart Way

How To Ask Questions The Smart Way Eric Steven Raymond Thyrsus Enterprises <[email protected]> Rick Moen <[email protected]> Copyright © 2001,2006,2014 Eric S. Raymond, Rick Moen Revision History Revision 3.10 21 May 2014 esr New section on Stack Overflow. Revision 3.9 23 Apr 2013 esr URL fixes. Revision 3.8 19 Jun 2012 esr URL fix. Revision 3.7 06 Dec 2010 esr Helpful hints for ESL speakers. Revision 3.7 02 Nov 2010 esr Several translations have disappeared. Revision 3.6 19 Mar 2008 esr Minor update and new links. Revision 3.5 2 Jan 2008 esr Typo fix and some translation links. Revision 3.4 24 Mar 2007 esr New section, "When asking about code". Revision 3.3 29 Sep 2006 esr Folded in a good suggestion from Kai Niggemann. Revision 3.2 10 Jan 2006 esr Folded in edits from Rick Moen. Revision 3.1 28 Oct 2004 esr Document 'Google is your friend!' Revision 3.0 2 Feb 2004 esr Major addition of stuff about proper etiquette on Web forums. Table of Contents Translations Disclaimer Introduction Before You Ask When You Ask Choose your forum carefully Stack Overflow Web and IRC forums As a second step, use project mailing lists Use meaningful, specific subject headers Make it easy to reply Write in clear, grammatical, correctly-spelled language Send questions in accessible, standard formats Be precise and informative about your problem Volume is not precision Don't rush to claim that you have found a bug Grovelling is not a substitute for doing your homework Describe the problem's symptoms, not your guesses Describe your problem's symptoms in chronological order Describe the goal, not the step Don't ask people to reply by private e-mail Be explicit about your question When asking about code Don't post homework questions Prune pointless queries Don't flag your question as “Urgent”, even if it is for you Courtesy never hurts, and sometimes helps Follow up with a brief note on the solution How To Interpret Answers RTFM and STFW: How To Tell You've Seriously Screwed Up If you don't understand.. -

Ebook - Informations About Operating Systems Version: August 15, 2006 | Download

eBook - Informations about Operating Systems Version: August 15, 2006 | Download: www.operating-system.org AIX Internet: AIX AmigaOS Internet: AmigaOS AtheOS Internet: AtheOS BeIA Internet: BeIA BeOS Internet: BeOS BSDi Internet: BSDi CP/M Internet: CP/M Darwin Internet: Darwin EPOC Internet: EPOC FreeBSD Internet: FreeBSD HP-UX Internet: HP-UX Hurd Internet: Hurd Inferno Internet: Inferno IRIX Internet: IRIX JavaOS Internet: JavaOS LFS Internet: LFS Linspire Internet: Linspire Linux Internet: Linux MacOS Internet: MacOS Minix Internet: Minix MorphOS Internet: MorphOS MS-DOS Internet: MS-DOS MVS Internet: MVS NetBSD Internet: NetBSD NetWare Internet: NetWare Newdeal Internet: Newdeal NEXTSTEP Internet: NEXTSTEP OpenBSD Internet: OpenBSD OS/2 Internet: OS/2 Further operating systems Internet: Further operating systems PalmOS Internet: PalmOS Plan9 Internet: Plan9 QNX Internet: QNX RiscOS Internet: RiscOS Solaris Internet: Solaris SuSE Linux Internet: SuSE Linux Unicos Internet: Unicos Unix Internet: Unix Unixware Internet: Unixware Windows 2000 Internet: Windows 2000 Windows 3.11 Internet: Windows 3.11 Windows 95 Internet: Windows 95 Windows 98 Internet: Windows 98 Windows CE Internet: Windows CE Windows Family Internet: Windows Family Windows ME Internet: Windows ME Seite 1 von 138 eBook - Informations about Operating Systems Version: August 15, 2006 | Download: www.operating-system.org Windows NT 3.1 Internet: Windows NT 3.1 Windows NT 4.0 Internet: Windows NT 4.0 Windows Server 2003 Internet: Windows Server 2003 Windows Vista Internet: Windows Vista Windows XP Internet: Windows XP Apple - Company Internet: Apple - Company AT&T - Company Internet: AT&T - Company Be Inc. - Company Internet: Be Inc. - Company BSD Family Internet: BSD Family Cray Inc. -

Perl Baseless Myths & Startling Realities

http://xkcd.com/224/ 1 Perl Baseless Myths & Startling Realities by Tim Bunce, February 2008 2 Parrot and Perl 6 portion incomplete due to lack of time (not lack of myths!) Realities - I'm positive about Perl Not negative about other languages - Pick any language well suited to the task - Good developers are always most important, whatever language is used 3 DISPEL myths UPDATE about perl Who am I? - Tim Bunce - Author of the Perl DBI module - Using Perl since 1991 - Involved in the development of Perl 5 - “Pumpkin” for 5.4.x maintenance releases - http://blog.timbunce.org 4 Perl 5.4.x 1997-1998 Living on the west coast of Ireland ~ Myths ~ 5 http://www.bleaklow.com/blog/2003/08/new_perl_6_book_announced.html ~ Myths ~ - Perl is dead - Perl is hard to read / test / maintain - Perl 6 is killing Perl 5 6 Another myth: Perl is slow: http://www.tbray.org/ongoing/When/200x/2007/10/30/WF-Results ~ Myths ~ - Perl is dead - Perl is hard to read / test / maintain - Perl 6 is killing Perl 5 7 Perl 5 - Perl 5 isn’t the new kid on the block - Perl is 21 years old - Perl 5 is 14 years old - A mature language with a mature culture 8 How many times Microsoft has changed developer technologies in the last 14 years... 9 10 You can guess where thatʼs leading... From “The State of the Onion 10” by Larry Wall, 2006 http://www.perl.com/pub/a/2006/09/21/onion.html?page=3 Buzz != Jobs - Perl5 hasn’t been generating buzz recently - It’s just getting on with the job - Lots of jobs - just not all in web development 11 Web developers tend to have a narrow focus. -

GNU Emacs Manual

GNU Emacs Manual GNU Emacs Manual Sixteenth Edition, Updated for Emacs Version 22.1. Richard Stallman This is the Sixteenth edition of the GNU Emacs Manual, updated for Emacs version 22.1. Copyright c 1985, 1986, 1987, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007 Free Software Foundation, Inc. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with the Invariant Sections being \The GNU Manifesto," \Distribution" and \GNU GENERAL PUBLIC LICENSE," with the Front-Cover texts being \A GNU Manual," and with the Back-Cover Texts as in (a) below. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled \GNU Free Documentation License." (a) The FSF's Back-Cover Text is: \You have freedom to copy and modify this GNU Manual, like GNU software. Copies published by the Free Software Foundation raise funds for GNU development." Published by the Free Software Foundation 51 Franklin Street, Fifth Floor Boston, MA 02110-1301 USA ISBN 1-882114-86-8 Cover art by Etienne Suvasa. i Short Contents Preface ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 Distribution ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 2 Introduction ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 5 1 The Organization of the Screen :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 6 2 Characters, Keys and Commands ::::::::::::::::::::::: 11 3 Entering and Exiting Emacs ::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 15 4 Basic Editing -

The GNOME Desktop Environment

The GNOME desktop environment Miguel de Icaza ([email protected]) Instituto de Ciencias Nucleares, UNAM Elliot Lee ([email protected]) Federico Mena ([email protected]) Instituto de Ciencias Nucleares, UNAM Tom Tromey ([email protected]) April 27, 1998 Abstract We present an overview of the free GNU Network Object Model Environment (GNOME). GNOME is a suite of X11 GUI applications that provides joy to users and hackers alike. It has been designed for extensibility and automation by using CORBA and scripting languages throughout the code. GNOME is licensed under the terms of the GNU GPL and the GNU LGPL and has been developed on the Internet by a loosely-coupled team of programmers. 1 Motivation Free operating systems1 are excellent at providing server-class services, and so are often the ideal choice for a server machine. However, the lack of a consistent user interface and of consumer-targeted applications has prevented free operating systems from reaching the vast majority of users — the desktop users. As such, the benefits of free software have only been enjoyed by the technically savvy computer user community. Most users are still locked into proprietary solutions for their desktop environments. By using GNOME, free operating systems will have a complete, user-friendly desktop which will provide users with powerful and easy-to-use graphical applications. Many people have suggested that the cause for the lack of free user-oriented appli- cations is that these do not provide enough excitement to hackers, as opposed to system- level programming. Since most of the GNOME code had to be written by hackers, we kept them happy: the magic recipe here is to design GNOME around an adrenaline response by trying to use exciting models and ideas in the applications. -

Analisi Del Progetto Mozilla

Università degli studi di Padova Facoltà di Scienze Matematiche, Fisiche e Naturali Corso di Laurea in Informatica Relazione per il corso di Tecnologie Open Source Analisi del progetto Mozilla Autore: Marco Teoli A.A 2008/09 Consegnato: 30/06/2009 “ Open source does work, but it is most definitely not a panacea. If there's a cautionary tale here, it is that you can't take a dying project, sprinkle it with the magic pixie dust of "open source", and have everything magically work out. Software is hard. The issues aren't that simple. ” Jamie Zawinski Indice Introduzione................................................................................................................................3 Vision .........................................................................................................................................4 Mozilla Labs...........................................................................................................................5 Storia...........................................................................................................................................6 Mozilla Labs e i progetti di R&D...........................................................................................8 Mercato.......................................................................................................................................9 Tipologia di mercato e di utenti..............................................................................................9 Quote di mercato (Firefox).....................................................................................................9 -

Hacker Culture & Politics

HACKER CULTURE & POLITICS COMS 541 (CRN 15368) 1435-1725 Department of Art History and Communication Studies McGill University Professor Gabriella Coleman Fall 2012 Arts W-220/ 14:35-17:25 Professor: Dr. Gabriella Coleman Office: Arts W-110 Office hours: Sign up sheet Tuesday 2:30-3:30 PM Phone: xxx E-mail: [email protected] OVERVIEW This course examines computer hackers to interrogate not only the ethics and technical practices of hacking, but to examine more broadly how hackers and hacking have transformed the politics of computing and the Internet more generally. We will examine how hacker values are realized and constituted by different legal, technical, and ethical activities of computer hacking—for example, free software production, cyberactivism and hactivism, cryptography, and the prankish games of hacker underground. We will pay close attention to how ethical principles are variably represented and thought of by hackers, journalists, and academics and we will use the example of hacking to address various topics on law, order, and politics on the Internet such as: free speech and censorship, privacy, security, surveillance, and intellectual property. We finish with an in-depth look at two sites of hacker and activist action: Wikileaks and Anonymous. LEARNER OBJECTIVES This will allow us to 1) demonstrate familiarity with variants of hacking 2) critically examine the multiple ways hackers draw on and reconfigure dominant ideas of property, freedom, and privacy through their diverse moral 1 codes and technical activities 3) broaden our understanding of politics of the Internet by evaluating the various political effects and ramifications of hacking. -

Introduction to FOSS (Free and Open Source Software) Department Elective – Syllabi Department of Computer Engineering, MNIT Jaipur

Introduction to FOSS (Free and Open Source Software) Department Elective – Syllabi Department of Computer Engineering, MNIT Jaipur 1. Unit 1 – Introduction to the FOSS philosophy (2 hrs) Overview of Free/Open Source Software, Definition of FOSS & GNU, History of GNU/Linux and the Free Software Movement, Advantages of Free Software and GNU/Linux, FOSS usage, trends and potential: global and Indian; Popular FOSS alternatives to non-free software (GIMP, OpenOffice, GAIM, Firefox, Thunderbird etc.) 2. Unit 2 – GNU/Linux Basics (8 hrs) GNU/Linux OS installation, detecting hardware, configuring disk partitions & file systems and install a GNU/Linux distribution, Basic shell commands - logging in, listing files, editing files, copying/moving files, viewing file contents, changing file modes and permissions, process management, User and group management, file ownerships and permissions, PAM authentication, Introduction to common system configuration files & log files, Configuring networking, basics of TCP/IP networking and routing, connecting to the Internet (through dialup, DSL, Ethernet, leased line and Wifi). Configuring additional hardware - sound cards, displays & display cards, network cards, modems, USB drives, CD writers. 3. Unit 3 – GNU/Linux Advanced (8 hrs) Understanding the OS boot up process; GNU/Linux distributions – case study of Fedora Core, Debian and Gentoo; basic understanding of the Linux kernel, kernel configuration, installing Linux from Scratch, understanding the Gnome and KDE environments and their components, Various -

Third Party Terms for Modular Messaging 3.0 (July 2005)

Third Party Terms for Modular Messaging 3.0 (July 2005) Certain portions of the product ("Open Source Components") are licensed under open source license agreements that require Avaya to make the source code for such Open Source Components available in source code format to its licensees, or that require Avaya to disclose the license terms for such Open Source Components. If you are a licensee of this Product, and wish to receive information on how to access the source code for such Open Source Components, or the details of such licenses, you may contact Avaya at (408) 577-7666 for further information. The Open Source Components are provided “AS IS”. ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE ARE DISCLAIMED. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE COPYRIGHT HOLDERS OR THE CONTRIBUTORS OF THE OPEN SOURCE COMPONENTS BE LIABLE FOR ANY DIRECT, INDIRECT, INCIDENTAL, SPECIAL, EXEMPLARY, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES (INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, PROCUREMENT OF SUBSTITUTE GOODS OR SERVICES; LOSS OF USE, DATA, OR PROFITS; OR BUSINESS INTERRUPTION) HOWEVER CAUSED AND ON ANY THEORY OF LIABILITY, WHETHER IN CONTRACT, STRICT LIABILITY, OR TORT (INCLUDING NEGLIGENCE OR OTHERWISE) ARISING IN ANY WAY OUT OF THE USE OF THE PRODUCT, EVEN IF ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGE. Avaya provides a limited warranty on the Product that incorporates the Open Source Components. Refer to your customer sales agreement to establish the terms of the limited warranty. In addition, Avaya’s standard warranty language as well as information regarding support for the Product, while under warranty, is available through the following web site: http://www.avaya.com/support. -

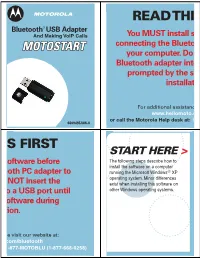

Com/Bluetooth

® And Making VoIP Calls www.hellomoto.c or call the Motorola Help desk at: 1 6809495A86-A The following steps describe how to install the software on a computer running the Microsoft Windows® XP operating system. Minor differences exist when installing this software on other Windows operating systems. com/bluetooth 1-877-MOTOBLU (1-877-668-6258) ® 1 2 Welcome to Bluetooth software. Stop all running programs and insert the installation CD into the CD-ROM drive. The installation starts automatically and guides you through the installation. If the installation does not start automatically, find the SETUP.exe file on the CD and double click it to start the installation. Accept license agreement. Confirm or change software 3 4 destination location. 5 Start installation. 6 Installation begins. 7 Bluetooth device not found message 8 Insert adapter into USB port. Click OK displays. Do NOT respond until you in Bluetooth device message (see install the adapter. step 7) if installation does not continue. 9 Complete the installation and 10 Verify Bluetooth adapter is ready to restart your computer. receive and transmit data (LED is solid blue). Right click and select Start Using 11 Bluetooth. Start Using Bluetooth MOTOROLA and the Stylized M Logo are registered in the US Patent & Trademark Office. The Bluetooth trademarks are owned by their proprietor and used by Motorola, Inc. under license. Microsoft, Windows, ActiveSync, Windows Media, and MSN are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation; and Windows XP, Windows Mobile and Microsoft.net are trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. All other product or service names are the property of their respective owners.