Land Acquisition, Public Purpose, Fair Compensation, Eminent Domain, Willing Land Giver, Binary Logistics Regression Model, Comb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India: Deaths in West Bengal During Protest Against New Industrial Project

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL Public Statement India: Deaths in West Bengal during protest against new industrial project As protests by farming communities fearing displacement from their land as a result of a new industrial project continue to lead to violence in West Bengal (Eastern India), Amnesty International is concerned at reports that state officials may be responsible for, or complicit in, human rights abuses including torture and the death or injury of protestors following the use of excessive and unnecessary force. At least seven people were reported killed and at least 20 others injured since 7 January in continuing violence in Nandigram, Eastern Midnapore district, West Bengal where farmers are protesting an initiative by the Bengal state government to acquire land for a new industrial project. Among those killed was a 14-year-old boy. Violent clashes in Nandigram reportedly involved members of the local Krishjami Raksha Committee (Save Farmland Committee) and persons linked to the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M), which leads West Bengal’s Left Front government and is seeking to accelerate the development of industrial projects in the state. Human rights organisations allege that the farmers were attacked by armed men affiliated to the CPI-M acting in complicity with the police. The reports say the attackers fired at the farmers and branded some of them with hot iron rods as ‘‘punishment’’ for protesting against the industrial project. There have been reports of farmers carrying out attacks on local CPI-M offices in the -

Prout in a Nutshell Volume 3 Second Edition E-Book

SHRII PRABHAT RANJAN SARKAR PROUT IN A NUTSHELL VOLUME THREE SHRII PRABHAT RANJAN SARKAR The pratiika (Ananda Marga emblem) represents in a visual way the essence of Ananda Marga ideology. The six-pointed star is composed of two equilateral triangles. The triangle pointing upward represents action, or the outward flow of energy through selfless service to humanity. The triangle pointing downward represents knowledge, the inward search for spiritual realization through meditation. The sun in the centre represents advancement, all-round progress. The goal of the aspirant’s march through life is represented by the swastika, a several-thousand-year-old symbol of spiritual victory. PROUT IN A NUTSHELL VOLUME THREE Second Edition SHRII PRABHAT RANJAN SARKAR Prout in a Nutshell was originally published simultaneously in twenty-one parts and seven volumes, with each volume containing three parts, © 1987, 1988, 1989, 1990 and 1991 by Ánanda Márga Pracáraka Saîgha (Central). The same material, reorganized and revised, with the omission of some chapters and the addition of some new discourses, is now being published in four volumes as the second edition. This book is Prout in a Nutshell Volume Three, Second Edition, © 2020 by Ánanda Márga Pracáraka Saîgha (Central). Registered office: Ananda Nagar, P.O. Baglata, District Purulia, West Bengal, India All rights reserved by the publisher. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording -

Paper 9 Contemporary History of India from 1947-2010

1 DDCE/PAPER-9 Contemporary History of India from 1947-2010 By Dr. Manas Kumar Das 2 CONTENT Contemporary History of India from 1947-2010 Unit.No. Chapter Name Page No UNIT- I. The Legacy of Colonialism and National Movement : a. Political legacy of Colonialism. 3-13 b. Economic and Social Legacy of Colonialism. 14-29 c. National movements: Its significance, Value and Legacy 30-48 Unit.II. The making of the Constitution and consolidation as a new nation. a. Framing of Indian Constitution - Constituent Assembly – Draft Committee Report – declaration of Indian Constitution, Indian constitution- Basic Features and Institutions 49-74 b. The Initial Years: Process of National Consolidation and Integration of /Indian States – Role of Sardar Patel – Kashmir issue- Indo – Pak war 1948; the Linguistic Reorganization of the States, Regionalism and Regional Inequality. 75-105 UNIT – III . Political developments in India since Independence . a. Political development in India since Independence. 106-121 b. Politics in the States: Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Assam, West Bengal and Jammu and Kashmir, the Punjab Crisis. 122-144 c. The Post-Colonial Indian State and the Political Economy of Development : An Overview 145-156 d. Foreign policy of India since independence. 157-162 UNIT – IV. Socio-Economic development since independence. a. Indian Economy, 1947-1965: the Nehruvian Legacy Indian Economy, 1965-1991, Economic Reforms since 1991 and LPG 163-175 c. Land Reforms: Zamindari Abolition and Tenancy Reforms, Ceiling and the Bhoodan Movement, Cooperatives and an Overview, Agriculture Growth and the Green Revolution And Agrarian Struggles Since Independence 176-205 c. Revival and Growth of Communalism 206-215 b. -

Narratives of Peasant Resistance at Nandigram, West Bengal in 2007

‘The blessed land’: narratives of peasant resistance at Nandigram, West Bengal, in 2007 Adam McConnochie A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Victoria University of Wellington 2012 ii Abstract In early 2007, the West Bengal state government in India sought to acquire over 10,000 acres of cultivated rural land in Nandigram, East Midnapur. The government, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI-M) led Left Front coalition, sought to acquire this land to allow the Indonesian industrialists, the Salim group, to construct a chemical hub. Land acquisition had been increasing in India since 2005, when the Special Economic Zone (SEZ) Act was passed for the purpose of attracting investment from national and multinational corporations. Peasants in Nandigram were opposed to the acquisition of their land, and during 2007 successfully resisted the government attempts to do so. In response, the CPI-M sent party cadre to harass, rape and murder the peasantry, using their control of government to punish people in Nandigram. This thesis examines the events at Nandigram between June 2006 and May 2008 and investigates the narratives of peasant resistance that emerged in West Bengal. It focuses on three groups of West Bengal society: the peasants of Nandigram, the intellectuals and civil society of West Bengal, and the major political parties of West Bengal. Existing explanations of the events at Nandigram have focused on the role of intellectuals and civil society, and their views have dominated the literature. The existing historiography has argued that land acquisition policies and the subsequent resistance at Nandigram were an effect of neoliberal policies, policies that had been pursued by both the central and state governments in India since the 1990s. -

Determinants of Voting Behaviour in the Assembly Elections in West Bengal: Theoretical Perspective

The International journal of analytical and experimental modal analysis ISSN NO:0886-9367 Determinants of Voting Behaviour in the Assembly Elections in West Bengal: Theoretical Perspective Dr. Md Motibur Rahman1 Guest Faculty, Department of Geography Rajendra College, Jai Prakash University, Chapra Email: [email protected] Rumana Khatun2 Research Scholar, Department of Geography Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh Email: [email protected] Abstract: Voting bahaviour is a form of electoral behaviour which clearly understands voter’s behaviour that can explain how and why political decision was made. Voting behaviour is also known as political psychology of the electors. The study of determinants of voting behaviour constructs a very significant area of empirical observation. Man is a rational animal in the philosophical sense of term, but he is not so rational in terms of economic and political behaviour. The study of voting behaviour displays the important facts that the behaviour of man is influenced by many socio-economic and political factors and also influences on the minds of the voters. The main purpose of the present study is to focus on the concept and definition of voting behaviour and highlight the significant factors that determine the voting behaviour in the assembly elections in West Bengal. Key Words:Assembly Election, Determinants, Electoral Geography, Voting Behaviour. Introduction Geography provides accurate, orderly, and rational description and interpretation of the variable character of the earth surface. It is that discipline that seeks to describe and interpret the variable character from place to place of the earth as the world of man (Richard Hartshorne, 1959).Geography deals with the spatial distribution of the phenomena and the processes through which such phenomena gets generated. -

Consolidated Daily Arrest Report Dated 12.06.2021 Sl

CONSOLIDATED DAILY ARREST REPORT DATED 12.06.2021 SL. No Name Alias Sex Age Father/ Spouse Address PS of District/PC of Ps Name District/PC Case/ GDE Ref. Accused Name residence residence Name of Accused 1 Subod Roy M 37 Dharani Kanta Bindipara PS: Samuktala Alipurduar Samuktala Alipurduar Samuktala PS Case No : Roy Samuktala Dist.: 109/21 US- Alipurduar 447/325/326/307/34 IPC 2 Mukesh Darjee M 35 Lt Shyam Beech TG PS: Jaigaon Jaigaon Alipurduar Jaigaon Alipurduar Jaigaon PS Case No : Pariyar Pariyar Dist.: Alipurduar 96/21 US-498A/494/34 IPC 3 Pollad M 35 Sumanta 11 NO. WARD PS: Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar PS GDE No. Biswas Biswas Alipurduar Dist.: 502 Alipurduar 4 Bipul Modak M 32 Giranjan Modak BAROCHOWKI PS: Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar PS GDE No. Alipurduar Dist.: 502 Alipurduar 5 Provat Das M 37 Protiva Das KHOLTA PS: Cooch Cooch behar Coochbehar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar PS GDE No. behar Dist.: 502 Coochbehar 6 Nepal Nama M 29 Jagmohan Das NATABARI PS: Cooch Cooch behar Coochbehar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar PS GDE No. Das behar Dist.: 502 Coochbehar 7 Subhankar M 37 Dinesh Ch Saha HARTAKITALA PS: Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar PS GDE No. Saha Alipurduar Dist.: 502 Alipurduar 8 Ganga Ch M 36 Sathan Gope GHARGHARIYAHAT Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar PS GDE No. Gope PS: Alipurduar Dist.: 502 Alipurduar 9 Tapan M 43 Kalachand BIRPARA PS: Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar PS GDE No. Sarkar Sarkar Alipurduar Dist.: 502 Alipurduar 10 Bapi Barman M 39 Suku Barman BIRPARA PS: Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar PS GDE No. -

Indian Tribunal Pushes for Sexual-Violence Inquiry

November 5, 2007 Indian Tribunal Pushes for Sexual-Violence Inquiry A citizens’ report in India highlights the sexual violence suffered last March by villagers in Nandigram and calls for a special trial of local authorities. Despite media coverage of the report the government has not responded. By Aparna Pallavi, WeNews correspondent CALCUTTA, India (WOMENSENEWS) – The testimony of 25-year-old Gouri Pradhan, a resident of the village Gokul Nagar, is typical in its description of the type of sexual assault that women say they suffered at the hands of police during violent land disputes that began last March in Nandigram, a rural area in the eastern state of West Bengal. “I went to attend the rally when the police started firing teargas and bullets simultaneously,” Pradhan testified from her hospital bed after the attack. “I tried to flee, when three policemen caught me and dragged me by the hand and into an empty house. I was beaten so badly that I was in no condition to resist. One of the policemen held my arms while two of them forcefully raped me. Then I lost consciousness and I don’t know if the third policeman also forced himself on me or not. I don’t know how I came here. I regained my consciousness in the hospital.” Kajal Gharai, from the village of Shonachura, also testified: “I got shot on my right shoulder. When I tried to flee the police chased me, caught me and ripped all my clothes off. They stripped me naked, kicked me and threw me in a corner. -

Operation Taslima on 22 Nd of November, 2007

Some published articles On oust Operation Taslima on 22 nd of November, 2007 1 Let Her Be EDITORIAL In response to demands from a few religious fundamentalists, India's democratic and secular government has placed a writer of international repute under virtual house arrest. Shorn of all cant, that is what the Centre's treatment of Taslima Nasreen amounts to. She was forced into exile from her native Bangladesh because of the books she had written. Now it looks as if the UPA government is about to repeat the same gesture by placing intolerable restrictions on her stay in India. She is living under guard in an undisclosed location. She will not be allowed to come out in public or meet people, including her friends. Without quite saying so, the government is clearly sending her a message that she isn't welcome in India and ought to leave. Earlier, she was turfed out of West Bengal by the state government. It's not quite clear who's ahead in the competition to pander to fundamentalist opinion, the Centre or the West Bengal 2 government. Earlier, Left Front chairman Biman Bose had said that Taslima should leave Kolkata if her stay disturbed the peace, but had to retract the statement later. Now external affairs minister Pranab Mukherjee echoes Bose by asking whether it is "desirable" to keep her in Kolkata if that "amounts to killing 10 people". In other words, if somebody says or writes something and somebody else gets sufficiently provoked to kill 10 people, then it is not the killer's but the writer's fault. -

Narratives of Peasant Resistance at Nandigram, West Bengal In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington ‘The blessed land’: narratives of peasant resistance at Nandigram, West Bengal, in 2007 Adam McConnochie A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Victoria University of Wellington 2012 ii Abstract In early 2007, the West Bengal state government in India sought to acquire over 10,000 acres of cultivated rural land in Nandigram, East Midnapur. The government, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI-M) led Left Front coalition, sought to acquire this land to allow the Indonesian industrialists, the Salim group, to construct a chemical hub. Land acquisition had been increasing in India since 2005, when the Special Economic Zone (SEZ) Act was passed for the purpose of attracting investment from national and multinational corporations. Peasants in Nandigram were opposed to the acquisition of their land, and during 2007 successfully resisted the government attempts to do so. In response, the CPI-M sent party cadre to harass, rape and murder the peasantry, using their control of government to punish people in Nandigram. This thesis examines the events at Nandigram between June 2006 and May 2008 and investigates the narratives of peasant resistance that emerged in West Bengal. It focuses on three groups of West Bengal society: the peasants of Nandigram, the intellectuals and civil society of West Bengal, and the major political parties of West Bengal. Existing explanations of the events at Nandigram have focused on the role of intellectuals and civil society, and their views have dominated the literature. -

India – Howrah – West Bengal – Political Stability – Election-Related Violence – Hindus – Religious Violence

Migration Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA MRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND35014 Country: India Date: 11 June 2009 Keywords: India – Howrah – West Bengal – Political stability – Election-related violence – Hindus – Religious violence Questions 1. Please provide information about the political stability of the West Bengal region of India and whether there is any reported violence between Hindus and other religious groups. RESPONSE 1. Please provide information about the political stability of the West Bengal region of India and whether there is any reported violence between Hindus and other religious groups. The sources consulted provided some information on political and religious violence in the Howrah district, and related information regarding West Bengal more generally. Political stability The UK Home Office report released in May 2009 cites Jane’s Sentinel Risk Assessment dated 17 October 2007, which identifies “a growing communist (Naxalite) insurgency which currently affects 13 of India’s 28 states,” including West Bengal. The report explains that concern over the insurgency was heightened by a 2004 “merger between the two leading Naxalite groups, namely the Maoist Communist Centre and the People’s War, to form the Communist Party of India-Maoist (CPI-M).” A surge of violence in 2005 resulted in 893 deaths throughout the country, with the report noting an “increasing sophistication of attacks, occasionally involving hundreds of rebels (UK Home Office 2009, Country of Origin Information Report – India, May, p. 48 – Attachment 1). Similarly, the US Department of State terrorism report for 2008 indicates that the Communist Party of India (Maoists), also commonly known as Naxalites, were active in a number of states, including West Bengal, who form what is referred to as the “Red Corridor.” It is argued that “[c]ompanies, Indian and foreign, operating in Maoist strongholds were sometimes targets for extortion (US Department of State 2009, Country Reports on Terrorism for 2008, April, p. -

West Bengal Final Quire.Pmd

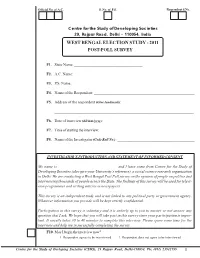

Official No. of A.C. S. No. of P.S. Respondent S.No. Centre for the Study of Developing Societies 29, Rajpur Road, Delhi - 110054, India WEST BENGAL ELECTION STUDY - 2011 POST-POLL SURVEY F1. State Name: ___________________________________ F2. A.C. Name: ___________________________________ F3. P.S. Name: ____________________________________ F4. Name of the Respondent: ____________________________________________________ F5. Address of the respondent (Give landmark): _____________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ F6. Date of interview (dd/mm/yyyy): ____________________ F7. Time of starting the interview: ___________________ F8. Name of the Investigator (Code Roll No.): ________________________________________ INVESTIGATOR’S INTRODUCTION AND STATEMENT OF INFORMED CONSENT My name is ______________________________ and I have come from Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (also give your University’s reference), a social science research organization in Delhi. We are conducting a West Bengal Post Poll survey on the opinion of people on politics and interviewing thousands of people across the State. The findings of this survey will be used for televi- sion programmes and writing articles in newspapers. This survey is an independent study and is not linked to any political party or government agency. Whatever information you provide will be kept strictly confidential. Participation in this survey is voluntary and it is entierly up to you to answer or not answer any question that I ask. We hope that you will take part in this survey since your participation is impor- tant. It usually takes 30 to 40 minutes to complete this interview. Please spare some time for the interview and help me in sucessfully completing the survey. F10. May I begin the interview now? 1. -

To Read Issue 14 of Update Magazine [PDF, English]

UPDATE SERIES 14 SEZ Juggernaut: Blood on the Wheels The Road to “Industrialisation”, “Development”... Genocide in Nandigram: A Dossier “Nandigram Syndrome” pervades India Changes in SEZ Acts: ‘One step backward, two steps forward’ Mirage of ‘China Model’ Labour Standards in Chinese SEZs Violent Land-grab in China April 2007 Address for Correspondence Update 14B, BB Block, Salt Lake, Kolkata – 700064, West Bengal, India Phone: (033)23217686, 9433196728 e-mail: [email protected] Edited, Published and Printed by Suvro Mallick on behalf of Update, 14B, BB Block, Salt Lake, Kolkata – 700064, West Bengal update 14 2 SEZ Juggernaut: Blood on the Wheels Well before the inking of the projects of chemical hub (SEZ) in Nandigram with the Benny Santoso of Salims — the Indonesian tycoons — on 31st July of 2006 — tensions and oppositions were brewing in East Midnapur where vast stretches of land were earmarked to be acquired. Times News Network reports on 23.06.2006: ...[A] sizeable section stood on the other bank of the Haldi river during Santoso’s visit on Wednesday, resenting government’s land acquisition drive. That perhaps explains why these people couldn’t cross the river. “Do you have a piece of land? Otherwise, you won’t realise the pangs of losing the roots,” a visibly angry Seikh Safiur Rahman of Rajaramchak village told TOI [Times of India]. The next stop was Char-Kendemari. Villagers here mobbed the car and wanted to know where it came from. “Good that you are from the media. Otherwise, we would have smashed the car,” locals said. On Wednesday, these villagers organised street meetings at Kendemari, Bar-Kendemari Chak to “thwart government’s bid to grab agricultural land”.