“The Forgotten Helpers? Life After the Emergency Services”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ctif News International Association of Fire & Rescue

CTIF Extra News October 2015 NEWS C T I F INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF FIRE & RESCUE Extra Deadly Fire Roars through Romanian Nightclub killing at least 27 people From New York Times OCT. 30, 2015 “Fire tore through a nightclub in Romania on Friday night during a rock concert that promised a dazzling pyrotechnic show, killing at least 27 people and spreading confusion and panic throughout a central neighborhood of Bucharest, the capital, The Associated Press reported. At least 180 people were injured in the fire at the Colectiv nightclub, according to The Associated Press”. 1 CTIF Extra News October 2015 CTIF starts project to support the increase of safety in entertainment facilities “Information about the large fires always draws a lot of interest. This is especially true in the case when fire cause casualties what is unfortunately happening too often. According to available data, fire at Bucharest nightclub killed at least 27 people while another 180 were injured after pyrotechnic display sparked blaze during the rock concert. The media report that there were 300 to 400 people in the club when a fireworks display around the stage set nearby objects alights. It is difficult to judge what has really happened but as it seems there was a problem with evacuation routes, number of occupants and also people didn’t know whether the flame was a part of the scenario or not. Collected data and testimonials remind us on similar fires and events that happened previously. One of the first that came to the memory is the Station Night Club fire that happened 12 years ago. -

Questionnaire Surveys

CHAPTER 8 SUMMERLAND SURVIVORS TELL THEIR STORIES 8.1 Questionnaire Surveys Solomon and Thompson (1995) conducted a psychological survey of Summerland survivors in 1991. Their study also looked at survivors of the Zeebrugge ferry (1987) and Hillsborough (1989) football ground disasters. Questionnaires were sent to 67 survivors of the Summerland fire disaster following advertisements on radio and in newspapers. Twenty-four questionnaires were returned, which is a response rate of 36%. In addition, questionnaires were sent to 16 people (seven responded) named by the Summerland Fire Commission as being responsible in varying degrees for the disaster. This enabled a comparison to be drawn between the disaster’s effects on the named individuals and the members of the public present at Summerland on the evening of the fire. As the questionnaire sought to gauge the survivors’ current feelings, respondents were specifically instructed to disregard all previous feelings about the disaster and answer all the questions in the context of their feelings over the seven days before the arrival of the questionnaire. Each survivor was asked to answer not at all, rarely, sometimes or often to the following questions. 1. I thought about it when I did not mean to. 2. I had waves of strong feelings about it. 3. I had dreams about it. 4. I tried not to think about it. 5. Any reminder brought back feelings about it. 6. My feelings about it were numb. 634 Each survivor was then asked questions about their general health, including whether they had lost sleep over worry or had been feeling nervous and anxious all the time. -

Evacuation Response Behaviour in Unannounced Evacuation of Licensed Premises

Fire and Materials EVACUATION RESPONSE BEHAVIOUR IN UNANNOUNCED EVACUATION OF LICENSED PREMISES Journal: Fire and Materials Manuscript ID FAM-16-0033.R1 Wiley - Manuscript type: Special Issue Paper Date Submitted by the Author: n/a Complete List of Authors: Boyce, Karen; University of Ulster, FireSERT, Built Environment McConnell, Nigel; University of Ulster, FireSERT Shields, Jim; University of Ulster, FireSERT, Built Environment evacuation, nightclub, alcohol, response behaviour, bar/nightclub, Keywords: engineering data http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/fam Page 1 of 20 Fire and Materials 1 2 3 4 EVACUATION RESPONSE BEHAVIOUR IN 5 UNANNOUNCED EVACUATION OF LICENSED 6 7 PREMISES 8 9 10 Karen Boyce, Nigel McConnell, Jim Shields 11 FireSERT, School of the Built Environment, Ulster University, UK 12 13 14 ABSTRACT 15 16 An understanding of the behaviour of individuals and groups during evacuation is key to the 17 18 development of evacuation scenarios as part of an engineering design solution. Furthermore, 19 it is important that engineers have reliable and accurate data on pre-evacuation times and 20 movement for use in time based evacuation analysis. This paper presents, for the first time in 21 the published literature, a detailed analysis of an unannounced evacuation of licensed 22 premises and provides important data and understanding regarding behaviour for use in fire 23 safety engineering design and evacuation modelling. Findings on recognition times, response 24 behaviours, pre-evacuation times and final exit flows for a function room and lounge bar in 25 the licenced property are provided. The results suggest that the evacuation time in the lounge 26 bar was characterised by generally longer pre-evacuation times and relatively shorter 2827 movement times, whereas the evacuation time in the more densely populated function room 29 was characterised by shorter pre-evacuation times but extended flow times. -

Nationalisation of Fire Service Becomes a Burning Issue

Emergency Services Ireland NATIONALISATION OF FIRE SERVICE BECOMES A BURNING ISSUE REMOTE DIGITAL RESPONDERS IN DISASTER ZONES LIMERICK MAN’S HIMALAYAN CHARITY CLIMB BID IRISH SOLDIERS ON SNOW PATROL TRAINING in SWITZERLAND issue 45 24 5 NEWS UPDATE 54 SPECIAL REPORT Sentencing for sexual crimes, under scrutiny 21 GLOBAL LEADERSHIP following recent high-profile cases in which Deputy Garda Commissioner Noirín sentences, are perceived as too lenient. O’Sullivan will join other emergency service leaders to address a global leadership 59 LIFESAVING conference in Belfast (31 July-1 August), FounDATION which is being held as part of the run-up to The presentation of the Ireland Medal for the 2013 World Police and Fire Games. 2012 to John Connolly is a fitting tribute to the founder of the Irish Lifesaving 23 ORDER OF MALTA Foundation, which celebrated its 10th Fundraising drives and other preparations anniversary at its recent conference on are well underway for the 30th Annual the promotion of research into the global Order of Malta International Camp in drowning epidemic. 42 August. Ireland’s Order of Malta aims to recruit over 250 Irish volunteers for the 67 SCOTTISH FIRE week-long event in Kildare. INVESTIGATIONS Current and future challenges for fire 24 FirE SERVICE investigation in Scotland were outlined by Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council Prof Niamh Nic Daeid from the University is now looking at a part-time fire and rescue of Strathclyde, at a recent conference service instead of earlier proposals for organised by the FIAI. privatisation, but just how successful has privatisation worked in other countries? 74 MOUNTAIN SURVIVAL For the past 15 years the Swiss army has 31 WilDFIRE MANAGEMENT been training foreign troops in mountain Collaboration between the authorities is skills as part of Switzerland’s contribution 74 the best way to stamp out wildfire incidents to NATO’s Partnership for Peace project. -

Questionnaire Surveys

CHAPTER 8 SUMMERLAND SURVIVORS TELL THEIR STORIES 8.1 Questionnaire Surveys Solomon and Thompson (1995) conducted a psychological survey of Summerland survivors in 1991. Their study also looked at survivors of the Zeebrugge ferry (1987) and Hillsborough (1989) football ground disasters. Questionnaires were sent to 67 survivors of the Summerland fire disaster following advertisements on radio and in newspapers. Twenty-four questionnaires were returned, which is a response rate of 36%. In addition, questionnaires were sent to 16 people (seven responded) named by the Summerland Fire Commission as being responsible in varying degrees for the disaster. This enabled a comparison to be drawn between the disaster’s effects on the named individuals and the members of the public present at Summerland on the evening of the fire. As the questionnaire sought to gauge the survivors’ current feelings, respondents were specifically instructed to disregard all previous feelings about the disaster and answer all the questions in the context of their feelings over the seven days before the arrival of the questionnaire. Each survivor was asked to answer not at all, rarely, sometimes or often to the following questions. 1. I thought about it when I did not mean to. 2. I had waves of strong feelings about it. 3. I had dreams about it. 4. I tried not to think about it. 5. Any reminder brought back feelings about it. 6. My feelings about it were numb. 544 Each survivor was then asked questions about their general health, including whether they had lost sleep over worry or had been feeling nervous and anxious all the time. -

Local History Files and Newspaper Files

Dublin City Library and Archive, 138 - 144 Pearse Street, Dublin 2. Tel: +353 1 6744999 Local History Files and Newspaper Files Heading Subheading Cabinet Drawer Item Date Collection number 1916 Newspapers and Journals 3 1 1916 Local History Files 1916 Signatories of the Proclamation 3 1 1916 Local History Files Act of Union 1 1 1800 Local History Files Adoption 1 1 Local History Files Aer Lingus 1 1 Local History Files Agriculture 1 1 Local History Files Airfield House 1 1 Local History Files America 1 1 Local History Files 08 November 2010 Page 1 of 121 Heading Subheading Cabinet Drawer Item Date Collection number American Civil War Irish Involvement 1 1 Local History Files Annals (Dublin) 1 1 Local History Files Antrim County File 7 4 Local History Files Archaeology 1 1 Local History Files Architects 1 1 Local History Files Architecture Dublin, General 1 1 Local History Files Architecture, Buildings A - F Aldborough House, Amiens Street, Also known as 1 1 Local History Files the Luxembourg, Feinaglian Institute Architecture, Buildings A - F Annesley House 1 1 Local History Files Architecture, Buildings A - F Apothecaries' Hall 1 1 Local History Files Architecture, Buildings A - F Aras an Uachtarain 1 1 Local History Files 08 November 2010 Page 2 of 121 Heading Subheading Cabinet Drawer Item Date Collection number Architecture, Buildings A - F Assembly House 1 1 Local History Files Architecture, Buildings A - F Ball's Bank 1 1 Local History Files Architecture, Buildings A - F Belvedere House, Great Denmark Street 1 1 Local History Files -

Mccartan-Report-Into-Stardust-Fire.Pdf

REPORT OF THE ASSESSMENT INTO NEW AND UPDATED EVIDENCE INTO THE CAUSE OF THE FIRE AT THE STARDUST, ARTANE, DUBLIN ON 14TH FEBRUARY 1981 Contents 1. Summary 2 2. Outline 4 3. Keane Tribunal 5 4. Coffey Review 7 5. Assessment of New Evidence 19 • Geraldine Foy’s Qualifications 21 • Outline of New Evidence 22 • Brenda Kelly 24 • Storeroom 27 • Lamp Room wall 33 • Electrical Fault 35 • Phelim Kinahan 36 • Bodies in North Alcove 38 • Michael Norton 41 • Dr Robert Watt 41 • David Mansfield Tucker 43 • Dr Sile Willis 43 • Paragraph 6.119 Keane 44 • External Witnesses 45 • Chapter 7 Keane 45 • Melted Glass 46 • PJ Murphy 47 6. Conclusion 47 7. Appendix 48 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1. On 7th March 2017, the Government established this Assessment to evaluate new and updated evidence uncovered by the Stardust Relatives and Victims Committee. 1.2. This is the third assessment of evidence into the Stardust Fire. The first was the original Tribunal of Investigation chaired by Mr Justice Keane in 1981. The second, an independent examination of the Stardust Victims Committee’s case for a re-opened inquiry, was carried out by Mr Paul Coffey in 2008. He submitted a report to the Department of Justice in December 2008 and a revised report in January 2009. 1.3. A dossier representing the case for a new enquiry was delivered to this Assessment on 6th July 2017, followed by two further files of attachments on 13th July 2017. The dossier and attachments were compiled by Ms Geraldine Foy, researcher and proof read by Paul O’Sullivan, solicitor. -

'Panic' and Human Behaviour in Fire

http://www.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/irc 'Panic' and human behaviour in fire NRCC-51384 Fahy, R.F.; Proulx, G. July 13, 2009 A version of this document is published in / Une version de ce document se trouve dans: Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Human Behaviour in Fire (Robinson College, Cambridge, UK, July 13, 2009), pp. 387-398 The material in this document is covered by the provisions of the Copyright Act, by Canadian laws, policies, regulations and international agreements. Such provisions serve to identify the information source and, in specific instances, to prohibit reproduction of materials without written permission. For more information visit http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/showtdm/cs/C-42 Les renseignements dans ce document sont protégés par la Loi sur le droit d'auteur, par les lois, les politiques et les règlements du Canada et des accords internationaux. Ces dispositions permettent d'identifier la source de l'information et, dans certains cas, d'interdire la copie de documents sans permission écrite. Pour obtenir de plus amples renseignements : http://lois.justice.gc.ca/fr/showtdm/cs/C-42 ‘PANIC’ AND HUMAN BEHAVIOUR IN FIRE Rita F. Fahy, PhD National Fire Protection Association Guylène Proulx, PhD National Research Council of Canada Lata Aiman, PhD School of Psychology, Deakin University ABSTRACT The word 'panic' is frequently used in media accounts and statements of survivors of emergency evacuations and fires, but what does it really mean, is it a phenomenon that actually occurs? This paper will review the definitions, and present evidence of behaviour from actual fire incidents that may have been misreported or misinterpreted as panic. -

Camp - the Next Generation

National Directorate for Fire and Emergency Management CAMP - THE NEXT GENERATION FURTHER DEVELOPMENT OF FIRE SERVICES COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION FACILITIES CONTENTS Executive summary 3 1 Introduction to Document 5 1.1 Introduction 5 1.2 Report Layout 5 2 CAMP Background 6 2.1 CAMP Project Development 6 2.2 Project Structure 7 2.3 Review of Project Development 8 2.4 Benefits Achieved 9 2.5 Current System Overview 13 2.6 Recognised Weaknesses of the Current System 17 3 Current Issues 18 3.1 Drivers for the Review 18 3.2 National Context 19 3.3 Impact of HSE Consolidation 20 3.4 CMOD Initiatives 20 3.5 Developing the Current 'Shared Services' Model 23 3.6 International Trends 24 4 Description and Appraisal of the Current CAMP IT and Communications Systems 29 4.1 Life-cycle of existing equipment 29 4.2 Systems Analysis 29 5 Future Direction and Vision 34 5.1 Introduction 34 5.2 User Requirements 36 5.3 Optimal use of Technology [Technical Analysis of Requirements] 37 5.4 Integrated ICT & Data 39 5.5 Automatic Vehicle Location Services and Satellite Navigation 40 1 6 Options for Change/Improvement 41 6.1 Introduction 41 6.2 Divesting Service Provision 42 6.3 From a Regional to a National System 47 6.4 No Change in System but Review Current Structure for Efficiency Gains 51 7 Implementation Planning 54 7.1 Overview 54 7.2 Key Work Packages 54 7.3 Overall timescales 56 8 Appendices 58 8.1 Terms of reference 58 9 Glossary 59 2 Executive Summary This Report describes a review of the current fire services Computer Aided Mobilisation (CAMP) facilities and arrangements. -

'Ireland's Search and Rescue'

Emergency Services Ireland IAA TAKES ON REMIT FOR CIVIL AVIATION SECURITY EMERGENCY RESPONSE PERSON OF THE YEAR IRISH TOP EU DRUGS TABLE SEEKING ‘LEGAL HIGHS’ ‘IRELAND’S SEARCH AND RESCUE’ AUTUMN TV LIFT-OFF MEDIA PARTNER OF 'SEARCH AND RESCUE EUROPE 2013' (19-20 MARCH, PORTSMOUTH, UK) issue 44 24 5 NEWS UPDATE 48 OVERSEAS AID Médecins Sans Frontières will host its first 19 EMERGENCY RESPONSE Student Humanitarian Challenge in Dublin AWARD this autumn to highlight the complexities Dublin Civil Defence volunteer Andrew faced by organisations in providing medical Connolly was presented with the inaugural aid to conflict zones around the world. ‘Emergency Response Person of the Year’ award at the LAMA 2013 Awards ceremony. 55 LOCATION MAPPING The introduction of new technology and 23 SAR EUROPE 2013 new post codes could dramatically improve ‘Emergency Services Ireland’ is the media location mapping services for paramedics 37 partner for ‘Search & Rescue Europe 2013’ who need to find homes or accident scenes in Portsmouth from 19 to 21 March, when quickly. RAF, arctic command and HM Coastguard will discuss SAR operation strategies and 61 DOMESTIC VIOLENCE case studies. As Women’s Aid continues to call on the Government to start the comprehensive 24 SEARCH & RESCUE review of domestic violence legislation it has Following the success of RTE’s popular promised, Director Margaret Martin outlines ‘Ireland’s Search and Rescue’ series, the her organisation’s recommendations to fourth instalment of the six-part series is on protect women and children from domestic the calendar for the autumn, with an even abuse. greater focus on the role played by the voluntary agencies. -

Ba Byrne G 2013.Pdf (337.4Kb)

A JOURNEY THROUGH MEMORY: AUDIENCE RESPONSE TO REELING IN THE YEARS THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE BA (HONS) FILM, LITERATURE AND DRAMA DUBLIN BUSINESS SCHOOL GILLIAN BYRNE SUPERVISORS: ANN-MARIE MURRAY AND PAUL HOLLYWOOD 30/05/2013 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................... 3 Table of figures ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Background to the Study ............................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Motivation for the Study ............................................................................................................... 8 CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ....................................................................................... 11 2.1 The Television Audience ............................................................................................................ 11 2.2 The Research Audience ............................................................................................................. -

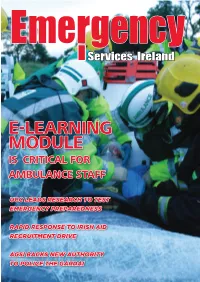

E-Learning Module Is Critical for Ambulance Staff

Emergency Services Ireland E-LEARNING MODULE IS CRITICAL FOR AMBULANCE STAFF UCC LEADS RESEARCH TO TEST EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS RAPID RESPONSE TO IRISH AID RECRUITMENT DRIVE AGSI BACKS NEW AUTHORITY TO POLICE THE GARDAI issue 48 21 3 NEWS UPDATE 63 INCIDENT RECORDING SYSTEM 21 CRITICAL INCIDENT Cork City Fire Brigade is the first emergency STRESS services agency in Ireland to purchase a The first eLearning module on Critical new incident recording and management Incident Stress Awareness Training, recently information system, following the launch of launched by the National Ambulance Service the ‘IRS Plus’, which has been designed for CISM (Critical Incident Stress Management) all fire and rescue services/mission critical Committee, aims to deliver a high standard services worldwide. of training to all members of the National Ambulance Service at all grades. 67 GP EMERGENCY CARE 35 A pre-hospital immediate medical care 27 EXTRICATION & TRAUMA training initiative is providing GPs and GP Carlow Fire & Rescue Service and Laois Registrars with updated and best practice Fire Service were the overall winners in both emergency care protocols, as well as the ‘RTC Extrication’ and ‘Trauma’ categories at confidence to deliver the practical skills this year’s National Extrication Challenge in necessary to implement them. Bray, Co. Wicklow. 71 SPECIAL REPORT 35 CFOA CONFERENCE An emergency homeless centre, opened by Fire officers, academics, industry experts Dublin Civil Defence earlier this year, has 45 and government and local government been forced to close its doors due to a lack officials from home and abroad will come of available resources. The Government together to discuss and debate ‘Leading is now planning to provide a sustainable the Fire Service of the Future’ at this year’s housing-led approach to homelessness.